Built By Subtraction: Video Games as Minimalism

Kieran Clarkin on Team ICO

I have two video game confessions to make.

One: my favourite games are those intended for children.

Two: I am bad at them.

The second follows naturally from the first - children’s games are often easier and therefore my lack of ability doesn’t mar the experience so much. Further to that, games made for an adult audience tend to engage in the most childish, immature definition of ‘adult’ – violent melodrama, gravel-voiced male leads - that the result is simply ridiculous and cheesy, if not outright offensive. A good example is last year’s big release, GTAV – for all its attempts to take itself seriously, the story elements are basically a 14 year old boy's fantasy.

At the same time, a lot of simpler games can feel like repetitive busy work and lose their joy quickly. Games can be art, we’re repeatedly told, but where in the infinite variation of the gaming landscape is the experience that feels like the equivalent of a good novel, film or album? Where is the sweet spot between mindless arcade or Pokémon collector/acquisition mentality, and an over-engineered, overwrought, cut-scene-stuffed blockbuster cheesefest of the AAA standards?

Unexpectedly, I stumbled across several of these games recently, a couple of years after their release. And while they’re not perfect, the unique emotional experience of these games was on par with the best you could expect from any fiction medium or piece of narrative art – the point where I actually lost myself, rather the kind of immersion we speak of when we actually mean ‘quite good and lifelike graphics’.

I doubt anyone would call me a 'gamer', but that's no great loss. 'Gamer' is a meaningless and inherently exclusive term that I am not fond of - if anything, Gamergate has reiterated that it's a grouping that's unhelpful to itself and poisonous to others . Plus, anyone who owns a smartphone and has downloaded Candy Crush is technically a gamer. I didn't play 'spacies' in my youth like a lot of my peers seemed to (obviously I smashed the buttons and jogged the sticks during the DEMO PLAY while waiting for fish and chips, but never actually sank those 20c pieces in). We didn’t have a Sega or Nintendo growing up, so I came to console gaming late and sporadically. I had some experience with friends' and siblings' Playstations before I left home for university and largely subordinated gaming to studying and socialising.

To be honest, most of the games played by my peers didn’t appeal - why spend hours simulating football when you can go out and kick one? I would like to say I objected to first person shooters on blanket moral grounds, but really it’s mostly because I always found them too difficult and frustrating. The adventure and fantasy elements of others never appealed; I had my fill of those in the comics I read. I've never had a problem with the 'video games are art!' argument because sure, what isn't art? But maybe I had a hard time thinking of Crash Bandicoot the same way I think about my favourite films and novels.

In fact, I never personally owned a gaming console until, on a whim, I bought a PS One last year for $30 from eBay. I really liked the design of this mini object and enjoyed revisiting some favourites from my teenage years, even if I was no better at them 10+ years later. I suppose I sought out these games in the same way I might have tried to track down a rare album or CD prior in the last century. It had a certain analog appeal. Since most modern culture became almost instantly available on a range of devices, we’ve lost a certain feeling of discovery and treasure hunting.

Finding that PS One games were relatively expensive, I had a look into the current and next-gen machines and my calculating, pragmatic instincts took over. I made a fairly expensive upgrade in order to play a game that was originally released in 2002. I missed out on most PS2 games - my buddy had a Playstation 2 but we mostly used it for Singstar. So it was only in passing that I somehow learned about ICO, which I was reminded of a couple of years ago at a video game exhibition. It had been bubbling away under my subconscious in the same way I always meant to listen to that other Neutral Milk Hotel album or watch The City of Lost Children.

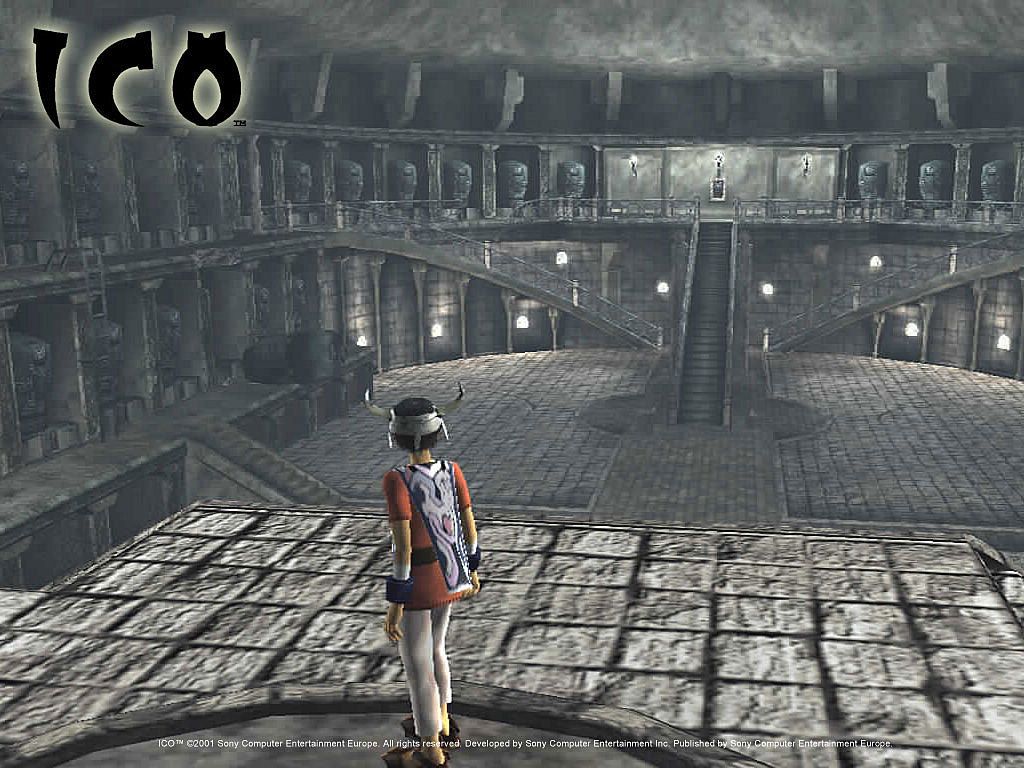

In ICO you play as the eponymous horned boy, trying to escape from the castle you have been imprisoned in as part of a ritual sacrifice. You befriend Yorda, a mildly spaced-out, ethereal girl who is also trapped. The gameplay is very simple; you can jump, climb, move things, call to Yorda and hold her hand. From one end of the castle, to the other a route is traced, all the while avoiding creepy shadow creatures and the evil queen. So far, so formulaic. It’s the sort of synopsis that’s essentially meaningless until you actually play it.

Because ICO is a game built by subtraction. Everything unnecessary to the story or gameplay is removed, and the result is compelling simplicity. That is not to say that it is a simple or facile game - the puzzles are tricky and the enemies can be tough. There are no heads-up displays, flashing alerts, radar screens or health and stat bars. With none of these distractions covering up the screen, Team ICO put all their effort into rendering an immersive, breathtaking environment. The ICO castle is a vertigo-inducing romance of a world. The visuals have a pronounced Mediterranean feel, as if the Castle could be found somewhere between Cadíz and Casablanca. The cover art, based on the work of Italian metaphysical artist Giorgio de Chirico, carries over into the feeling of the game.

Rather than using strictly ‘literal’ colouring (i.e. grass = green; sky = blue) the screens are completely influenced by sunlight and shadow. The pioneering bloom lighting effects contrast greatly to even modern games, which seem to use lighting in a prosaic, utilitarian and drably realist manner. There are very few music cues - in fact, the entire soundtrack only runs to twenty-three minutes. Ambient noise provides the majority of the audio, with fiercely gusting wind and chirping gulls, punctuated by the staccato of small feet slapping on cobblestones. Players may find themselves pausing between puzzles to admire to scenery or catch a glimpse of some new architectural oddity.

These are the elements that make the game beautiful and immersive. Combined they create a unique experience, but they don’t fully explain the emotional impact the game had. I’m not sure I’m equipped to explain this, or anything. For example, why are two Star Wars films good and the rest terrible? Why did Slaughterhouse 5 only leave me mildly depressed where The Time Traveller’s Wife had me weeping? My best guess is that this is usually due to a matter of character.

Ico and Yorda aren’t very chatty types, but they earn the player’s affection fairly quickly with the briefest of archetypal brushstrokes. Ico earns your sympathy through his unfair incarceration. Yorda attaches herself to Ico quickly, and both do their utmost to help each other against the spooky shadow creatures and the evil queen. The plot contains enough detail to make sense, but leaves a lot unexplained or open-ended. Like the gutter between comics panels, it allows the player to fill in the gaps themselves. It also avoids a lot of tedious exposition explaining the origin and back story of every character and the ‘revelatory’ connections between minor plot points (see: Metal Gear Solid franchise). Curiously, there’s even a prose adaptation of ICO despite the gossamer-thin source material. I can safely say it is the only video game novelisation I have ever considered reading.

Playing ICO inevitably led me to the 2006 follow up game from Team Ico, Shadow of the Colossus (if you’re playing the HD re-release, they’e bundled on the same disc). Director Fumita Ueda and his developers maintain their reductive design approach with Shadow, but start with the bare bones of a different genre: what if you had an RPG but removed everything except the boss fights?

In order to revive his dead girlfriend, a young man with a sword and a horse makes a deal with the devil to kill sixteen colossi. The game really is that straightforward: you ride in the direction of each colossus, kill it, wake up in Dormin's temple and repeat, until the game ends. This simple recap belies the emotional experience that SotC provides. The eight or so hours of a normal playthrough allows you to develop a bond with your steed Agro. This affection contrasts with the fact that you are steadily reducing the population of the land from seventeen to one. Being alone in such a vast, quiet landscape is unlike any other game experience I have ever had, where enemies and tasks pop up at every turn.

The landscape of Shadow of the Colossus, while often breathtaking, is utterly indifferent to you and your travels. Where ICO encourages exploration in order to discover and solve the puzzles that keep you from escaping the castle, it invites exploration with seemingly no reward on offer. Sure, there are white-tail lizards to catch and fruit to ‘pick’ with your arrow - but they are inessential to completing your tasks and the story.

ICO has a strongly defined environment – a mostly symmetrical castle built high into a rocky outcrop in the ocean, connected to the mainland by a long bridge. The landscape of SotC also features a long, forbidding bridge, but the environment is one of exhaustive variety. From beaches and craggy cliffs on the west and south capes, through forests, plains, deserts and muddy volcanic areas in the central mesa, leading to high-altitude lakes and mountains bordered by vast canyons to the east and the impassable wall to the North from whence you journeyed. Galloping through these mutable environments and changing climates leads you to the lair of each colossus. Whether subterranean, in the mountains or in the middle of a lake, they are marked by decaying structures, built long ago leaving no hint as to why or by whom.

It is possible, over several hours, to trot your way around every glen, crag, and hollow - but apart from the ubiquitous black lizards and the petrified corpses of felled colossi, there is very little to interact with. That emptiness, and accompanying sense of loneliness, is produced by the narrative and design elements but also by exploiting the nature of modern video games. If we think of film as a temporal medium, then games, increasingly, are a spatial one. If you have ever fallen in love with a game, or been compelled to hit that 100% complete mark for some ungodly reason, you may be familiar with that feeling of emptiness. Every gem collected, every enemy defeated, every boundary reached and the awareness that there is nothing beyond.

Even giant sandbox-style games like the GTA franchise share this problem. Once you have the nice apartment, cool suit, all the rare cars and all the guns, what is there? Both ICO and Shadow of the Colossus accept this limitation and embrace it. In ICO it reinforces the bond between Ico and Yorda, alone in a hostile universe. In Shadow of the Colossus, the only inhabitants of the fairly large expanse of terrain you traverse are the semi-sentient giants that you systematically kill. That emptiness adds to the tragedy of exterminating these magnificient one-of-a-kind beasts. The colossi appear as though they are hewn from the rocky landscape and life breathed into their granite and moss features. Each colossus is a puzzle to solve, using a combination of fairly simple skills: sword and bow, running and jumping, gripping and climbing. But what happens when you finally purge this landscape? The end of SotC provides enough revelatory details to satisfy the basic demands of the plot, but it leaves a lot unanswered and provokes new questions. It strikes the perfect balance of conventional elements and genuine weirdness that reminds me of the best folk or fairy tales I read growing up.

The attention to detail extends to the controls - that tactile hook-in that makes gaming a fundamentally different experience to just watching a screen. The centrality of the R1 shoulder button in both ICO and Shadow of the Colossus shifts the focus of gameplay. The constant use of that index finger for holding or gripping contrasts to the standard primary action in games of punching or shooting. In ICO, holding R1 calls Yorda to Ico and the two join hands; once released, Ico lets go. While holding hands with Yorda, her pulse beats faintly through the motors in the controller. In SotC, R1 is for gripping while you scale the shaggy beasts; releasing it will cause you to release your grip and fall off. These actions are reiterated at crucial story points. Neither game requires a high degree of skill or the use of complicated button combinations, yet the effect is as touching as it is perfunctory.

I have to admit that since completing both of these games (several times in fact, for Colossus) I have been fairly neglectful of my PS3. Apart from a short, wondrous game called Journey (devised by Thatgamecompany, a minnow of an American video game studio that must have surely grown up on Team Ico’s works), I’ve encountered precious few games that are made in the same spirit as ICO and Colossus. I’m not the first person to laud their praises, but I think one of the great strengths of both is actually one more key subtraction, a subtraction that everything else has seen as a vital and valuable addition for at least 20 years now. Put simply: no one talks, and it’s wonderful.

I have seldom met a game with anything approaching decent dialogue. A good way to increase the gulf between player and polygonal avatar is to have them say something profoundly stupid with some phoned-in B-list voice acting. Rather than working on harmonious game and story elements, the temptation these days seems to be to make a long, interactive CG movie, like Heavy Rain or Beyond: Two Souls. It’s hard to engage fully with a game that constantly reminds you of Hollywood’s worst excesses, that wishes it was one. The Last Of Us deals in terror, but terror is easy, especially in video games. It’s often used as a shortcut to emotional engagement, but running from zombies only gets you so far. Most games bludgeon you to get there – for an awfully long time by the standards of anything you’ll see on a screen, Team Ico’s two games simply leave you alone.

For obvious reasons, I don’t want to portray myself as some sort of rigid asceticist who survives on a simple diet of the same two minimalist computer games. Fact is, I’m not - I recently spent a couple of months playing Lego Marvel Super Heroes, which is fun but hits a different set of buttons, and now I’m finally trying Skyrim. But both ICO and Shadow of the Colossus offered me an experience I hadn't had before – a beautiful visual experience, an engaging emotional narrative, and a satisfying interactive interface where my actions had meaning. I'm not sure if that's the perfect distillation of a video game: maybe the tap-tap-tap of Flappy Bird is more pure, the gamification of Candy Crush Saga more sleek. But again, they’re busy work – a distraction for restless fingers.

I'm not sure if there is an ideal for video games. I mentioned near the beginning how a gamer is virtually anyone with a timewasting app on their phone now, and it basically casts playing games into the realm of movies, television and music. Everyone kind of likes it, some people consume too much, some people argue vehemently about it in lieu of real-life problems and solutions, and there’s a tonne of shit to get through to find something you like.

And perhaps different genres have different ideals, the way that the goals of a documentary differ from those of a comedy. One of those isn’t inherently bad, and one of those isn’t inherently good, but you might prefer the rules and parameters of one over the other. And when I read descriptions of Ueda and co’s long-delayed third game, The Last Guardian, I’m reminded of exactly the rules and parameters I like.

Rumors have been ramping up that The Last Guardian, in development (hell) for ten years, may finally see release on the PS4 in the near future. Sony continues to insist that it is being worked on. Pundits say it will never see the light of day, or that it will be an underwhelming victim of its own bloated gestation. In an ideal world we would see its release divested of any hype, another experience that only has to live up to its pedigree of what it is. But in a truly ideal world, the games of Team Ico wouldn’t be outliers of excellence in an industry devoted to a mediocre status quo.