Finding Yourself in the Whakapapa: A Year Reading Kaituhi Māori

Imagine reading for your entire life and never feeling seen in the words – the reality for many Indigenous, Black and minority readers. Ruby Solly on only reading Māori authors for a year.

I’ve always loved reading. As a child, it was a way for me to travel to places I never would have had access to in the real world. It was a way to learn about the wondrous places and ways of life I could only imagine. By describing worlds of magic with the same depth of language we use to talk about everyday happenings, it blurred the lines between fantasy and reality. As a child, reading, to me, was pure escapism.

But soon I grew, and so did my needs from books. It was no longer enough to be taken away from whatever world I was facing. I needed to see myself in those books and to see how people like me lived in the world. Because no matter where I went in the interim, I would always have to navigate te ao hurihuri; the ever-changing world around me. I always assumed this was a subtext that all young people would find in reading, but after reading enough foreign heartbreak stories and fantasies for a lifetime, my kete was still empty, while many of my friends’ kete were full.

“Sometimes mother and daughter amused themselves

with silent conversation.

They made pictures in their minds

that had nothing to do with their work.

Each concentrated to keep the pictures there

until the other could see them too.

It was a safe way for them to talk.

Nobody could be annoyed at their silence

and downcast eyes.”

Toi Te Rito Maihi, Pakakē! Pakakē! Whalesong

But again, I still loved reading and all it gave me. And of course, there were always glimpses of a deep knowing. An education that reaches down to your foundations and tells you things you already knew about yourself and your capabilities, but didn’t quite believe. Writing that affirms you. Then I found poetry by Māori authors such as Hone Tuwhare, Apirana Taylor and Hinemoana Baker. Those works were lifelines to me, aho into te ao Māori. But at that point they were just that; small lines to hold onto. Not strong enough on their own for me to climb.

After feeling under represented in my own reading for so long, I decided to set a goal of reading only works by Māori authors for a year. Initially, I thought this would be an opportunity to solidify my identity as a Māori writer and to learn from our pakeke and kaumātua. Of course, it did all of this for me and my work. But it did so much more for my connections with others, for knowing who I am, and knowing my purpose within te ao Māori.

At the start of my year of reading, I met my favourite book of the journey. I finished Patricia Grace’s Cousins in one day, perched on the rocks by Aotea Harbour. By the time I was at the end, I was crying so much I had to pause before I could read again. Reading that book felt like I’d lived three lives in a day, and in it I could feel the characters Mata, Makareta and Missy weaving together with my own past, present and future. It gave me a kind of longing for the childhood I did have, and the one that I didn’t. It showed me what could have been, and yet it taught me who I am and where that could take me. How that could bring me home, to a home I hadn’t even met yet.

“The first time I go home,

it’s by looking into a whites aviation frame.

Recoloured pastel, in colours seafoam and mint.

Its op shop frame cracking

from years hung in a bathroom

in a different time.

I ask to go there in person,

but in this financial landscape,

other things are coming first.

My mother throws handfuls of salt

into the bathtub.

Turns the lights off, and tells me to listen

to the rain on the tin.

I hear the water splash the rocks as my skin adapts

to the shallows.”

Ruby Solly, ‘Dear Captain’

Cousins left me feeling seen by a work of literature for one of the first times in my life. I wasn’t escaping into the book, I was in it. It was like having your story told to you, and, of course, we need to kill our darlings. There were parts of me I didn’t like, and it hurt to see them and to watch them damage the right sides of me. It hurt to see the way the damaged parts of me were going to grow until maybe they would take over my life entirely. In a house with my mother’s family, I had never felt so alone. This book had shown me worlds that had been closed to me; some worlds recent, and some so far away that I didn’t even know if the people who inhabited them knew I was missing them at all.

Families are complicated things. I no longer have the stereotypical massive Māori family that I once did. Climbing fruit trees with my cousins, and being passed around every aunty and uncle. There are various reasons for this, and over time I’ve come to understand that none of them was my fault. But they were still my reality, and the more I read these books the more I was shown myself in all my different angles, truths and phases of life. It was like reading something that predicted the future and showed me a manual on how to live. I somehow knew more about who I was, and less than I did before. But still, I read. I had a promise to myself to keep, and I was only five months in.

“Looking back towards the house she could see Makareta watching from the step and wondered if her cousin was going to come and have a turn. That morning the old grandmother had helped Makareta make her bed and had laid out her clothes for her, peering and poking at each garment, smoothing them out on the bed with picky fingers. When Makareta was dressed, the woman had sat her down on a stool and begun brushing her hair. Seen through the doorway from the kitchen where they were having breakfast, it was like looking through an opening into a room full of hair. After the brushing the grandmother had made fat plaits, which became narrower and narrower down past the stool seat, almost to the floor, tying with bows as neat as butterflies.”

Patricia Grace, Cousins

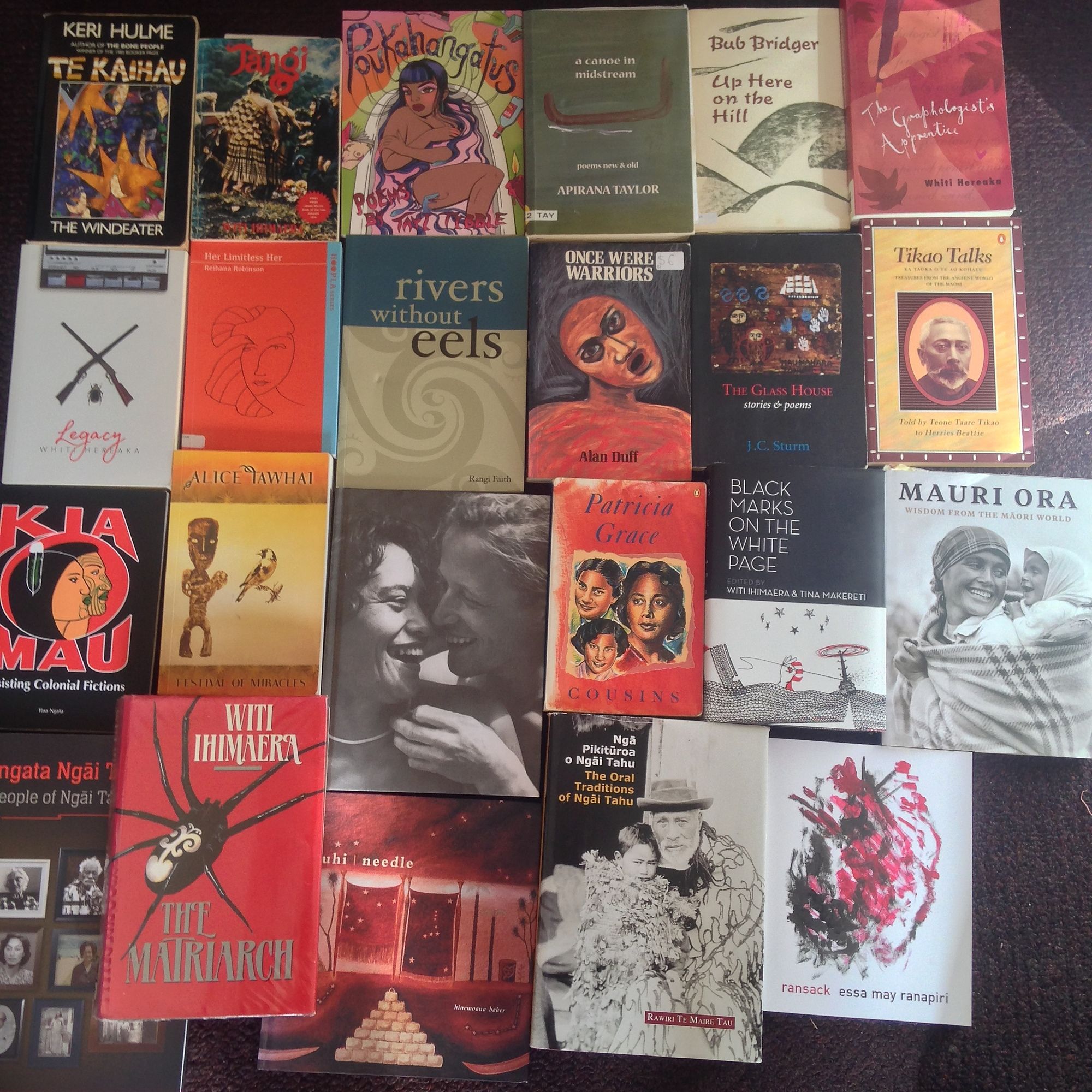

After a while, I had a new issue. Accessing books. I was told about the warped statistics around Māori and reading. In the past these were used against us, to limit the publishing of Māori authors. As my haerenga continued, this became more and more apparent. I’d go into bookstores and ask what Māori authors they had and they’d say Witi Ihimaera and Patricia Grace. I’d tell them how much I loved both those authors, and ask if they had anything else. They’d often say, “There isn’t anything else.” But then they’d be surprised when I came up to the counter overloaded with books, after spending an hour or so rummaging through shelves and shelves of secondhand books. Roma Potiki, Whiti Hereaka, Keri Hulme, Alice Tawhai, Apirana Taylor, Jacky Sturm – the list went on. Once I learned to dig, I never ran out of good things to read.

“Do I note here, the rough soft warmth of a homespun cloak? Who spun it for him? What spider woman? What spider man? The lichen colours of it: the broad bands ochre and yellow-orange and rusted brown and light green. How he drew off very carefully a single hair fallen from my head. Do I note the strong hands? The blunt nails? The ragged deliberately ragged cut hair? The smirk, undisguised, proud, inviting. The full and beautiful lips. The taut buttocks, cleft outlines, the washed denim. Do I pander to your imagination? This is my farewell, my particular fenestration.

Drink your own.”

Keri Hulme, ‘A Window Drunken in the Brain’, Te Kaihau – The Windeater

This whole time I was somehow on two journeys at once; one that assured me of who I was, and one that reminded me of all the things I didn’t get to be a part of. Growing up as Kāi Tahu living in the North Island, Te Wai Pounamu seemed like Disneyland. A dream that was out of reach. I went back for the first time at 20, and instead of finding the answers I had been waiting for I found only more questions. I learnt my pepeha from my aunty and nana, and spoke it on marae around the country – until I found out I’d been saying the wrong one. I had barely known who I was, and now I didn’t even have that anymore.

Lucky for me, I was part of a strong group of Māori writers, many of whom were Kāi Tahu and were there to awhi and support me. I was that kid who was welcomed into so many families. I had a seat at their table, but no whakapapa behind it. It was a feeling that left me feeling lucky and broken all at once.

On a book-hunting mission to Featherston, I found a book by Gerry Te Kapa Coates with a picture of the Waitaki River on the cover. When I was a child, my father once told me that the only gift from our culture he had left to give me was my name, Hinepunui, which had belonged to one of my ancestors. In the limited knowledge I had of my whakapapa, I knew that Hinepunui and Te Kapa were married, and their child was my grandmother's great-grandmother, Koukou. I thought that maybe I had found some sort of clue, but didn’t know what I’d found.

“You’d planned it

All along, right from birth

Although things, as even you know

Don’t always go to plan as

Catastrophes abound en route.

Meanwhile I inch inevitable to age

As youth rushes the desirable,

The inescapable

Planned back then.”

Gerry Te Kapa Coates, ‘There You Were (1)’, The View From Up There

I loved Gerry’s writing. Within one book, I saw those two sides of myself, the known and the unknown, intertwining. I read through first just to enjoy the work. And then again to look for clues. Gerry talked about Waihao – maybe that was where I was from. He spoke of other places, too, so I couldn’t be sure. I was too whakamā to try and make contact. But luckily for me, Gerry is a meticulous writer, with an engineer’s brain. He’d made footnotes for every poem, including one he’d dedicated to his daughter Arihia. Funnily enough, that was the name of one of the Kāi Tahu writers who had worked to awhi me during this time. I messaged and found out Gerry was her father, as I’d suspected. We scheduled a phone call.

Ruby, Gerry Coates and Arihia Latham with Joy Harjo and her partner at New Zealand Festival of the Arts 2020. On the table is a copy of Gerry’s book, a koha to Joy

It’s funny doing whakawhānaukataka over the phone. But there we were in our own spaces, whakapapa charts laid out across the floor. We started with Hinepunui and Te Kapa – a match. Then moved down to Koukou – a match again. Then down to Tieke – still a match. His first wife or second wife? A match. Then Lydia? Again, yes. After that, we descend from two sisters out of ten. It turns out that Gerry and my nana are first cousins, and my friend becomes my family in more ways than one.

Gerry and Ruby going over whakapapa and filling in some gaps

I go to Gerry’s house the following week. On the walls are old whānau photos that have been treasured by me for years. Different shots from the same day; sisters, all lined up in a row. We sat there, three writers from three generations of our whānau, breaking bread together. I learned that we were uri of Waihao, famous for its eels, of whānau who worked and travelled the Waitaki River. We come from a long line of proud, peaceful Waitaha and Kāi Tahu people who survived in te ao hou, this new world. In that simple meeting I regained so much of what I had lost, and gained some things that I thought I’d never had. Though I’ve realised now that I had them all along, I just had to go looking. I had to read my way back in.

“A sparrow flies inside the wharekai and my heart flaps // A sign//

Does it matter that it’s the wrong bird // It was the colonisers that brought the muskets//

Perhaps the thing to lay to rest is this genealogical trauma, to notice the elepha...sparrow in the room//

After all it’s not a pīwaiwaka bringing a tohu of the past or the future // Is time linear and do birds care//

My cousin Ruby is a songbird, we are sparrow and pīwaiwaka // Why can’t I sing like her//

She flings her arms and the sparrow finds the window //

I am carried by the current of wānanga // I wonder how the awa can keep cleansing us //

How does it keep on flowing to sea // I am eddying //

The karaka berries make the air sweet and fragrant // The poison is in the seed//

Our poison was in the seed // If you know how, the river can wash it away//”

Arihia Latham, ‘Rui Ruia’