There's Something Wrong With Art Writing

Have you ever looked at an art essay and had your eyes glaze over so hard you accidentally bought shares in Krispy Kreme? Vanessa Crofskey is sick of exclusive jargon.

Let’s start with a very real Master’s critique I was a part of:

Esteemed guest:These paintings reminds me of [redacted 19th century artist]

University Lecturer: Yes, but I would say that the style is more in the taste of [redacted 20th century artist]

Esteemed guest:I disagree, the line work here is not mid-20th in the slightest. If anything, it evokes a brutish German feel, sort of like [redacted European painter] or maybe the latter works of [Eastern European painter].

University Lecturer: I am actually reminded of [redacted European printmaker], [redacted American printmaker], [woman example].

Esteemed guest: If anything we can agree that it’s very [historical art movement that was concurrent with movements in architecture].

University Lecturer: Yes.

Esteemed guest: [silence]

University Lecturer: [silence]

University Lecturer: What does anyone else think?

Me: I like this canvas because it’s a nice shade of pink.

*

There’s something wrong with art. My heart tells me that art should be public, that people should not feel ashamed about getting it ‘right’ or behaving ‘wrong’ when standing in front of a portrait. My mum should be able to come into a gallery and feel excited and not panicked about what’s presented in front of her. But she won’t enter unless I accompany her.

The writing that exists about art should help bridge that lack of public understanding. Whether it’s a critical essay, artist statement, lecture or label, we should be cultivating the understanding of mainstream audiences alongside the arts-aware. If we content ourselves with living on the fringe, we’ll fade into irrelevance. Yet so often the language we speak exists less to assist and appeal, more to shame and alienate.

*

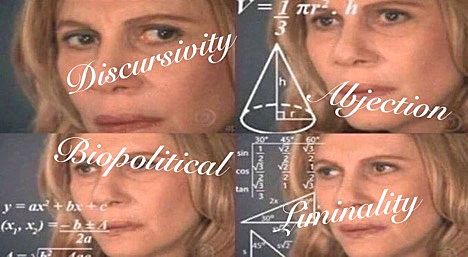

When I was at art school, the terms of art theory buzzed around like a joint at a house party. We could never just ‘like’ a painting, we pined over affect, rigid with desire at the table of Deleuze and Guattari. The sublime, we would whisper into a breath of smoke as Edmund Burke’s ghost hovered over our bodies. We’d take a deep inhale of dusty air-conditioned oxygen and exhale Acconci into the poorly painted walls. In that moment we were so acutely aware of the spatiotemporal logistics between public and private it was like the walls weren’t even visible, just concepts stapled to a silhouette. We didn’t ‘speak’ so much as engage in dialectics. The spaces between our desks weren’t in-betweens: they were resonant markers of transitory liminality; sites of serendipitous interaction; seminal Happenings affixed in symbiotic relations.

We consumed a choir of borrowed language and pressed our mouths into the jargon that made us feel legitimate. Nobody understood us, and that was the intention. The world was ending and Roland Barthes rose from dead latin prefixes.

After I graduated, the codified language didn’t disappear from my bookshelves. Nicolas Cage continued his hunt for the Da Vinci Code in the pages of Artforum.

*

International Art English is a term that’s the result of an extensive research project on art language, published in essay form for Triple Canopy. It analyses the confusing terms that have so often infiltrated attempts to write about art over the last 20 or 30 years. The short of it is that academic-sounding language has pervaded not just our Fine Arts 101 essays, but all text associated with the visual. As described by Alix Rule and David Levine:

IAE has a distinctive lexicon: aporia, radically, space, proposition, biopolitical, tension, transversal, autonomy. An artist’s work inevitably interrogates, questions, encodes, transforms, subverts, imbricates, displaces – though often it doesn’t do these things so much as it serves to, functions to, or seems to (or might seem to) do these things.

The reason behind using such language has a lot to do with authority, and the ways in which we wield it “to signal the assimilation of a powerful kind of critical sensibility, one that was rigorous, politically conscious, probably university trained.”

Art writing has been so informed by IAE that it’s become dull, confusing and robotic – even to the people who actually want to read it. Caring about what a piece of art is made out of, and what ideas it relates to, is one thing. But we’ve jargonised our responses to the point of oblivion.

As people who consume, care and write about art as more than just a hobby, it can feel frustrating to be excluded from the mainstream. It’s exhausting to have to fight to prove that people should care about something you care about, when your interests are so easily labelled as niche. But the response shouldn’t be to burrow further inside ourselves, behind the haughty defences of complex language. This means we exclude anyone else from joining in.

*

Let’s look at a few examples. Take this paragraph, from Terrence Handscomb for EyeContact. It’s a critical reading of David Hall’s culturally provocative essay ‘Admit Nothing: Mapping Denial’. I dare you not to skip any:

Hall adopts an aporetic form of deconstruction: “That which is undeniable can only be denied” is his foundational assertion. This is of course a logical antinomy. But for the subjects that inhabit a sovereign language of power and privilege, an aporetic impasse such as this marks exactly where denial lies. For some, however, deconstruction as a method of textual analysis has a reputation for being extremely dodgy, with Derrida being seen as its master-sophist orchestrator. So when deconstruction is imputed, ‘serious‘ philosophers will smell a rat. There are of course more robust repudiations of deconstruction than this...

Honestly, I don’t even know how to begin with this. I’ve read the paragraph multiple times and I still don’t understand it. Every time I have another go at unpacking what it means, I get hypnotised by a dictionary and have to skip to the finish line before I can google logical antimony.

Much like EyeContact, the Pantograph Punch isn’t exempt from relying on the verbose. It also deserves a roast or two for the way its essays start to feel like a labyrinth mated with a Rubik’s Cube. Here is Robyn Maree Pickens in a recent essay on Louise Menzies.

In an orange my mother was eating is rich with discursive relationships within and between artworks, such that a type of familial resemblance exists despite the disparate eras, styles, and practices of the three artists Menzies works alongside, and despite the different forms Menzies’ works take: digital video, prints set in handmade paper, framed Risograph print, textile, printed matter. The discursivity of Menzies’ interactions as they materialise into traditionally marginalised media such as textile and handmade paper (to name two prominent examples) perform distinctly feminist actions of retrieval, reinterpretation, recontextualisation and recirculation. Or to nuance that claim somewhat, it is the aspects of the three women’s practices that Menzies works with that individually and cumulatively offer an occasion to remember and re-evaluate what it is to be a female artist in a normatively heteropatriarchal (art) world.

Rough translation:

The artworks in In an orange my mother was eating bear a distinctive likeness to each other, despite different practices, artists, timelines and forms. These works use feminist materials. Traditionally ‘feminine’ media such as textiles and handmade paper speak to labour practices that have historically been sidelined. It is through integrating these three women’s works into her art that Menzies offers us an occasion to remember: what was it like to be a female artist in a male-dominated world? And does this experience still ring true for us today?

Neither am I immune from the trap of throwing decorative terms around like doilies. This was the last part of my undergrad contextual statement:

This project is more interested in an ongoing process of dialogic exchange than seeking a resolved solution. By continually reprocessing an accumulation of text, the work exposes the ruse of finality.

So I’m a sell-out – but one with a conscience.

It’s not the wildest take to denounce art as classist or to criticise its language as being intentionally exclusionary. It is a necessary stance to make. Art helps define culture, and can serve as an insidious arm of capitalism, classism and elitism. It’s not immune to being fucking full of itself, and neither are we. But it’s also a small, small pocket of rebellion, where we can choose the things we’d like to see. Where we can imagine the world we’d like to be in and the way we’d like to speak.

I’ve studied enough about violence and language to know that words can work as a structural form of oppression. The way we frame the world informs the way we interact with the world. It affects how we categorise objects and identities, where we put them on a value scale. If we want to stop parading around ‘diverse’ art and actually begin engaging with ‘outsider’ communities – both terms already deserve a red flag for the way that normalise whiteness and certain upbringings – then we need to shed the false tones we’re speaking in. We need to make our vocabulary much more soulful.

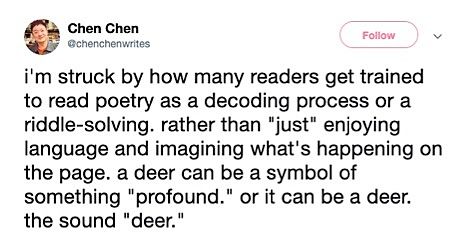

When thinking about how I interact with art and the writing that excites me, I turn to Twitter. In this day and age, Twitter feels like the only form of information my brain can process. It is home to some of my favourite arts minds accessible over the internet, with most of us finding temporary shelter to complain about the rain (read: industry). I think on this interaction between Chen Chen and Nina Powles, about poetry, and find that I can relate.

We shouldn’t be ashamed of carrying insider knowledge about a subject, or of finding exactly the right word to describe something. But my worry is that talented writers fall by the wayside because they’re reliant on words which are sector-specific. My worry is that arts writing has become more about showcasing intellectual prowess than informing and entertaining our readers.

What’s the point of using intellectually obscure terms if you’re sacrificing engagement? How can we speak about art from a place of permission? How can we humanise our vocabulary so art is an experience of joy, and not isolation?

It’s shameful to admit that I don’t understand or enjoy the majority of art writing. So much of it makes me feel disheartened, like a 9am lecture I’m blearily awake for. It makes me feel like I’m an impostor in the creative and academic community. Like if I cared more about this stuff, I would get it. But I do care, and I still don’t get it.

I grew up with access. I had the resources to excel in a classroom, a general grasp on Western terminology and cultural connection with the European thinkers we were taught to listen to. It pains me that in knowing where I feel I don’t belong, there’s a long, long line of people standing behind me.

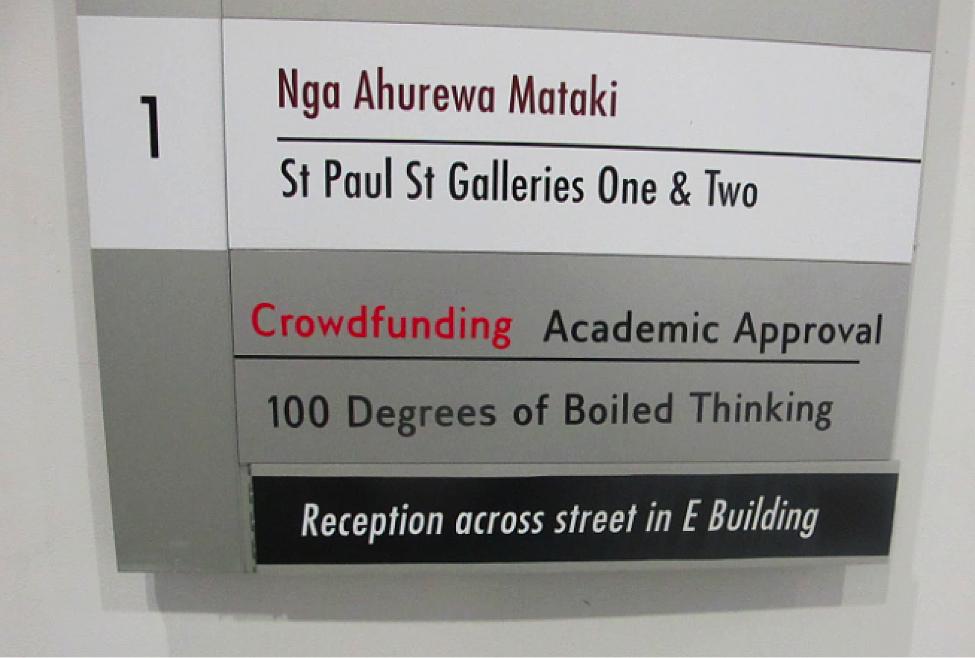

Here’s the challenge then: let’s open a door and build a bridge. Let’s opt into inclusion rather than assume that those who get it, will. We should talk about art in a way that doesn’t shut others off from the conversation or otherwise, we’re cutting ourselves short. I don’t want to belong to something that makes others feel small. So let’s question our intent, our audience, and who we’re omitting by default a little more thoroughly. Lest we stand at the crossroads holding stop signals. Lest room sheets read like obituaries. Lest we become the world’s biggest arseholes at parties.