James Franco and The Absurd

When we talk about the absurd, we refer to a way of life where what is valued is not the best living - the highest quality of living - but the most living. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus writes, "to two men living the same number of years, the world always provides the same sum of experiences. It is up to us to be conscious of them. Being aware of one's life, one's revolt, one's freedom, and to the maximum, is living, and to the maximum." For a long time, this idea of living the absurd life hugely appealed to me, and gave me justification to act in generally irresponsible and youthful ways.

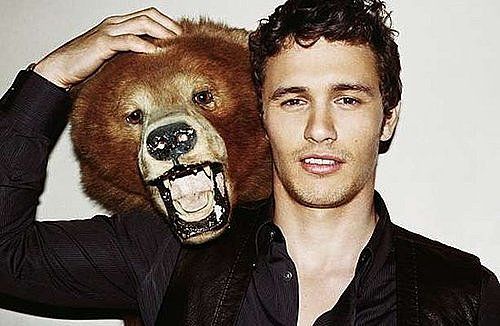

Recently I've been reading about James Franco and feeling intense admiration for his endless persistence, for truly is he living the absurd life. And frankly the quality of his work is irrelevant - the sheer aggressive passion through which he pursues it all is enough to make me love everything about it.

At age 28, ten years after dropping out, Franco decided to go back to college.

He persuaded his advisers to let him exceed the maximum course load, then proceeded to take 62 credits a quarter, roughly three times the normal limit. When he had to work—to fly to San Francisco, for instance, to film Milk—he’d ask classmates to record lectures for him, then listen to them at night in his trailer. He graduated in two years with a degree in English and a GPA over 3.5. He wrote a novel as his honors thesis.

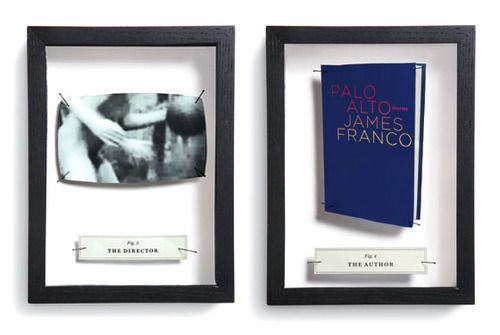

Take, for instance, graduate school. As soon as Franco finished at UCLA, he moved to New York and enrolled in four of them: NYU for filmmaking, Columbia for fiction writing, Brooklyn College for fiction writing, and—just for good measure—a low-residency poetry program at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina. This fall, at 32, before he’s even done with all of these, he’ll be starting at Yale, for a Ph.D. in English, and also at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Short stories he worked on at Columbia and Brooklyn College were published in Esquire and McSweeney’s. His NYU student films—including the artsy adaptations of poetry he was telling me about in the bathroom—graced all the major film festivals. His documentary Saturday Night, which began life as a seven-minute NYU assignment, blossomed—thanks to unprecedented behind-the-scenes access to SNL (a show Franco has hosted twice)—into a full-length feature.

“But what does that even mean?” he asks. He seems impatient, genuinely baffled. “Spreading himself too thin?”

Well, I say, isn’t it a reasonable concern? How many targets can one person’s brain realistically hit with any kind of accuracy?

“If the work is good,” Franco says, “what does it matter? I’m doing it because I love it. Why not do as many things I love as I can? As long as the work is good.”

His entire career is beginning to look less like an actual career than like some kind of gonzo performance piece: a high-concept parody of cultural ambition.