What Would Jack Do?: A Review of "Passio"

Alex Taylor finds an exquisite corpse exhumed.

Attending the patchwork Passio by Jack Body and friends, Alex Taylor finds an exquisite corpse at the Auckland Town Hall.

Amidst a calorific theatrical menu of circus and horror at Auckland Arts Festival, the music programme provided something quite different. To me, it seemed two themes ran through the festival’s music section: on one hand, highly collaborative and cross-cultural shows like AWA, The Bone Feeder, and Revolutions; on the other, an emphasis on retro, postmodern recontextualisation and (faded?) glory, with Rufus Wainwright, John Williams and early music ensemble L’Arpeggiatia.

Passio ticked both these boxes – a collaborative scheme devised by the late composer and musicologist Jack Body, combining 500-year-old sacred choral music with modern orchestrations. The authorship of the work is curious. The original Renaissance work is the Richard Davy setting of the Passion according to Saint Matthew (not to be confused with the more famous JS Bach setting of the same). Body – beloved by the musical community here and abroad – set up a framework for Davy’s Passion where he and five other New Zealand composers created musical responses over and between Davy’s work, to enliven, contrast, and disturb the original material. But as ‘Richard Davy’s Passio with commentaries by David Farquhar, Gillian Whitehead, Lissa Meridan, Michael Norris, Jack Body and Ross Harris’ is a bit of a mouthful, it has, in the promotional material, become simply ‘Jack Body’s Passio’.

Our reverence for Jack Body’s contribution and legacy can get in the way of making work in his true spirit.

The festival marketed it with maximum reverence: “a New Zealand treasure unearthed.” By the way that Carla van Zon waxed lyrical about Passio, one might think this was a lost masterwork of a bygone era, carefully reconstructed in honour of Jack’s recent passing. Listeners were asked to get in touch with memories of the original Wellington event – combining the Tudor Consort with the New Zealand Air Force Band, in the hyper-resonant acoustic of the Massey University Great Hall – so that the festival could piece together exactly what had happened. But in fact the original performance was only a decade ago, in 2006, and one can even hear it on YouTube - archaeology and reconstruction are hardly necessary.

I mention Jack’s standing in the community because it strikes me that our reverence for Jack’s contribution and legacy can get in the way of making work in his true spirit. Jack’s modus operandi was to do the most ambitious, outrageous thing he could think of, and put all of his energy into doing it (and into persuading other people to do it with him). He would have seen a restaging of Passio as an opportunity to improve it; to make the most of the expanded forces, the acoustic of the Auckland Town Hall, the context of the festival. What we got instead was simply the exhumation of an exquisite corpse.*

In Davy’s original St Matthew Passion, two soloists representing The Evangelist and Christ exposit much of the story of Christ’s Passion, in unaccompanied plainchant. These mesmerising (monotonous?) chants are interspersed with chorales carrying the words of the Apostles and the crowd.

During performance I played a matching game in my head (that bit was so Jack Body), and peered over the shoulder of a tuba player or percussionist to check my answers.

Although it leaves Davy’s vocal music essentially intact, Passio has a rather fragmentary nature: each composer creates one or two central memorable moments within their own section, so that instead of having a single dramatic arc to absorb, the audience experiences a journey of tangents. We were perambulatory, both musically and physically in the dusty light of the Town Hall: we wandered around and between the massed forces of the Auckland Chamber Orchestra and Voices New Zealand Chamber Choir, seeing and hearing the performance from every possible angle. The choir and orchestra were massed back to back in the middle of the hall, dominating the space, with the soloists perched at one end, and three smaller instrumental groups dotted around the edges.

Of course, given its near-religious respect, the festival honoured Body’s intention to tell the audience the names of the seven composers but not tell them who composed which section. It strikes me as rather pretentious to deliberately obscure the authorship of the work when it is not so much a collaboration as a patchwork, and obviously so, each composer presenting a clear aesthetic point of view. Not letting us in on the know is not subversive so much as vaguely irritating. So I couldn’t help myself – during performance I played a matching game in my head (that bit was so Jack Body), and peered over the shoulder of a tuba player or percussionist to check my answers.

The late David Farquhar’s opening instrumental commentary rather tentatively ornaments the Davy, with fragments of vocal lines dotted around the instruments. The mostly monophonic texture preserves the original character of the chant; this allowed the audience to ease into the work, while tentatively making their way across the Town Hall floor. Although Farquhar’s pacing is rather too restrained for my taste, the spare textures threw the excellent solo singers into relief. Carrying the bulk of the textual load, Lachlan Craig’s Evangelist was both effervescent and effortless, injecting light and life into a part that could have easily become soporific. Joel Amosa’s Christus was a fine foil to Craig’s tenor, with a rich bass-baritone that at times felt almost too operatic for the context.

The second section (Gillian Whitehead’s) experiments with antiphonal textures through the alternation of different timbral groups, and also the throwing of sound between similar instruments. This was particularly satisfying in the low percussion instruments, as timpani and bass drum blurred together in surround sound. Whitehead’s starker contrasts of colour extend to the introduction of breath sounds and spoken voices, an antagonistic thread that Body’s section tugs at later on. Harmonically we are drawn both forward, into areas close to atonality (or at least Stravinskian modality), and backward towards medieval organum. Passio points us in so many different stylistic directions that it builds up an appealing timeless quality. The crux of Whitehead’s music for me came near the end of the section, where a glorious chorus is interrupted by some rather rude water gong bends, in what seems like a deliberate act of subversion, even bathos. This is an about-face in tone, from something reverential to something quite alien, a palette cleanser for the brief but gorgeous saxophone chorales that follow.

In contrast, Lissa Meridan’s third section is a point of stasis, more homogeneous than Whitehead in both harmony and timbre, with delicate clusters of woodwind floating under and between the vocals. This seemed a slightly timid musical offering, until the texture built to a climax of ecstatic metallic percussion, a surprising and fantastical Messianic moment emerging out of the calm.

Michael Norris’s approach is quite different to what comes before, employing a rich post-Romantic harmonic language and making full use of the large brass section. Here there are hints of Scriabin, the music of film noir, and Shostakovich at his most rousing and acerbic. Norris perhaps takes the greatest risks in interacting directly with not only the chant but also the chorales, and in marrying such a bold aesthetic to the stark original. The risk pays off: this is an immersive, integrated language that complements the episodic nature of the text.

Jack Body’s fingerprints are all over this project: ambition, audience participation, the intersection of the sacred and the profane. So it’s no surprise that his compositional contribution is one of the most striking, a riot of colour and style. It’s tempting to imagine Jack wrote his section after seeing everyone else’s – such is the way he ties previous threads together – but perhaps it’s just a reflection of his Libran intuition. Whitehead’s organum comes back with descending parallel fifths in high winds; overlapping entries are reminiscent of both Norris and Meridan; repeated staccato notes recall the slightly doddery opening section. But it’s the gestural power of stamping, hissing, shouting and strident percussive outbursts, that really hits home. Subtlety takes a back seat: the band cry “crucify” and stamp their feet in eruptive swells.

The moments when the choir employed its full force (especially in the final two sections) were searing, the word “crucifigatur” (he is crucified) became etched into our memories.

In the printed programme, Whitehead suggests that the Town Hall “gives scope for a greater dramatic impact from the choir”, and she is bang on: the moments when the choir employed its full force (especially in the final two sections) were searing, the word “crucifigatur” (he is crucified) became etched into our memories. In a cathedral setting, the finesse and musicality of Voices New Zealand Chamber Choir would be much less obvious. While we missed the saturation and perhaps the meditation of a truly resonant space, the Town Hall gave us incision, clarity and warmth. It’s understandable that most of the audience ended up standing still in front of the choir: expertly led by conductor Karen Grylls, their chiselled, impassioned choruses were enough of a musical offering in themselves.

On the other hand, the Town Hall also encouraged a false reverence: the audience moved around awkwardly, aware of the slightest sound of shoes on the wooden floor. And one can’t help but feel the twinkle of Jack Body’s eye was missing from this performance: Peter Scholes’s expanded Auckland Chamber Orchestra were colourful and competent, but lacked the zeal of the choir, and frankly, needed more to do. Perhaps because they were writing for the extremely generous acoustic of the original venue, most of the composers only offer splashes of colour, rather than extended line or development.

After the sound and fury of Body’s penultimate section, the final episode is a curious mixture of Ross Harris doing Ross Harris – opening with ethereal low pedals in contrabass clarinet and double bass, and including a characteristically acerbic Mahlerian scherzo – and a brief but luminescent Madeleine Pierard, her voice winding heavenwards from Debussian pillars of sound reprising her 2006 role as Harris’s Spiritus. (One might draw parallels with the solo soprano at the end of Jack Body’s Carol to St Stephen, an ethereal solo voice representing the spirit of the martyr. Pierard has sung the solo part in that work too, as well as in Ross Harris’s second Symphony, written at the same time as Passio.) This section is packed full of anything and everything, and felt somewhat detached from the main arc of the work (perhaps acting more as a self-contained coda than a denouement). But Harris the symphonist knows how to engineer a dramatic ending. The long-awaited appearance of the spot-lit Pierard was itself a major event, and triggered a new percussive ferocity, before easing back into one last stretch of chant delicately adorned, and an emphatic final unison from the band.

As an experience, Passio was for me neither here nor there: neither compellingly dramatic, nor mesmerizingly meditative. Individually, many of the component parts shone: composers, conductors, choir, orchestra, soloists, lighting, the Town Hall itself. But the whole, reconstructed by committee and lacking the original passion of its instigator, fell short of the sum of its parts. With such a wealth of talent and resources, the project wouldn’t have suffered if it had sharpened its creative focus to really take us along for the ride. I’m sure it’s what Jack would have wanted.

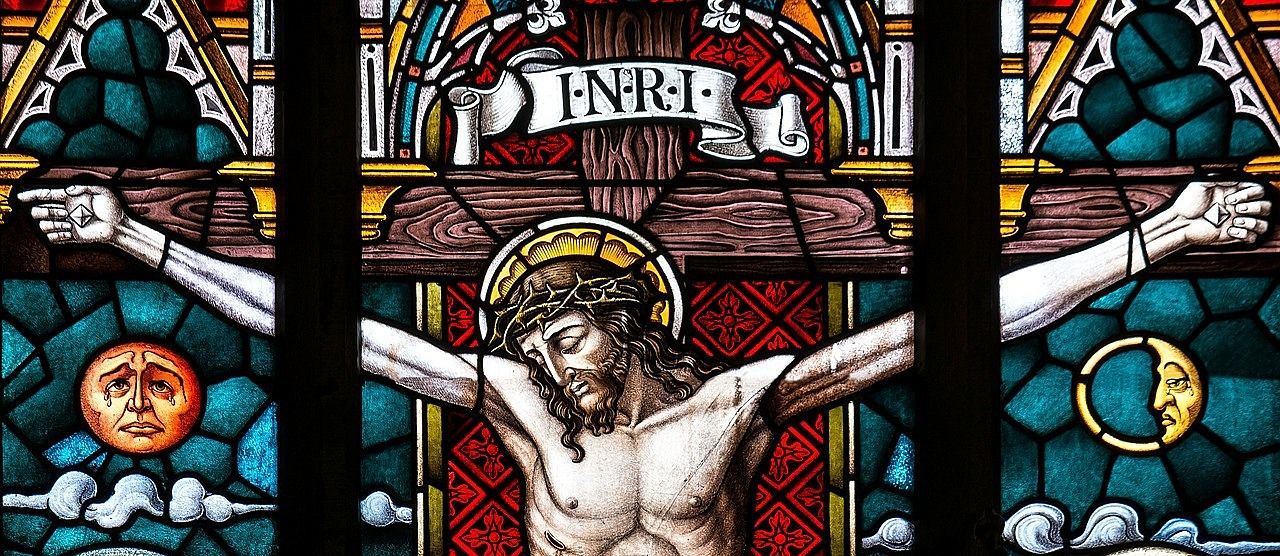

Header photo: Didgeman via pixabay