A Private History of Jonny Potts' Loose

Booze, Iggy Pop, Whangarei and Jonny Potts

It’s a full house for the first Wellington episode of The Watercooler. It’s miserable and cold out, but it’s hot in the BATS Studio. It’s always hot in the BATS Studio, a tiny 40-seat space looking out over Kent Terrace. It’s not long before jackets are off and windows are all fogged up.

Tonight’s theme is ‘Waiting’. Auckland comedian Freya Desmarais talks about her social anxiety and urinating on her deck in a rainstorm; Daniel John Smith, in a comfortable Swandri, kills with a poorly-scheduled office fashion show; Alice May Connolly, in an equally comfortable beanie, walks us through the ways her mother guilted her into behaving as a kid. After Alice, the host – Alice Brine (producer and inveterate comedy hustler) - introduces the fourth and final guest, Jonny Potts.

Jonny gets up from his seat on the stage. His roughly-combed mop of black hair – deceptively young, like everything else about Potts’ appearance - is controlled by a baseball cap.

“Isn’t it great,” he tells the audience, “How in the Auckland Watercooler they’re all, ‘What’s something cool and funny to say,’ but in Wellington we go, ‘A stage? And people? Better bare my soul!”

Jonny's story is called ‘How I Quit Smoking’. It's a story about his experience of a debilitating, terrifying, undiagnosed illness in June this year. At one point, he reprimands the audience for laughing too much.*

Loose: A Private History of Booze and Iggy Pop 1996-2015 is a comedy show in which Jonny Potts tells twenty stories about his life between 1996 and 2015, all of which feature alcohol and the Stooges frontman. It's a show defined by its constraints.

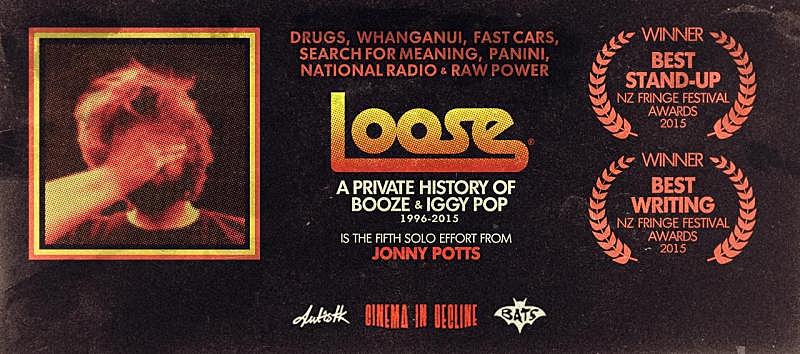

The poster says the show has 'drugs, Whanganui, fast cars, search for meaning, panini, National Radio and Raw Power.' The picture on the poster is of Jonny, hair mussed, right hand over his face. "The image, of me with my hand across my face," He pauses. It's late Friday night at Fringe Bar, a horseshoe-shaped hub in Wellington's increasingly diverse comedy ecosystem. Jonny's just taken a character for a road test at the Dank Comedy Show, a new stand-up night produced by Jundas Capone.

"That's a selfie I took in the South of France." Jonny pauses again. He does this a lot, planning the course of what he's saying. "I got the idea from a fresco I saw in Florence, in a monastery, of a saint - or of Jesus - covering his face and refusing to see something. It was a very clear idea of shame. And so I thought of flipping the idea."

I ask him if he can go into that a little further. "I suppose it's the idea of doing a show about things that only mean something to me. You know, you assume that's going to be self-indulgent, of limited interest, of little value, having little use in the world. Limited utility."

Loose premiered towards the end of this year's New Zealand Fringe Festival. Following its five-night season in the BATS Studio, it was nominated for seven New Zealand Fringe Awards, including Best of Fringe. It won two: Best Stand-Up Comedy and Best Writing. He also won the inaugural SYNZ Touring Award, a new 'performance exchange partnership' between the Sydney and New Zealand Fringe Festivals. It's playing Sydney this week.*

So who is Jonny Potts? Well, he's a Wellington comedian. He's been one since 2011 - "I can never lie about when I started stand-up, because my first set was about the Royal Wedding." He has a strong, resonant baritone: the kind of voice that could earn a nation’s trust from behind a newsdesk.

Jonny's start came at the same time as Wellington's comedy community was trying pull itself back onto its feet, following the disintegration of the Wellington Comedy Club. “It was bleak,” I’m told by Humorous Arts Trust co-founder Jerome Chandrahasen. They’ve come a long way: where once there was only one game in town, Raw Meat Mondays, there’s now a dedicated comedy club (VK’s Comedy & Blue Bars, in the old Big Kumara space), a slew of nights for new and established comedians alike, and infrastructure in place to help comedians develop their shows and their voices. Jonny came up within, and parallel to, this boom time.

Jonny's a regular fixture at a few of these nights, like The Medicine and Comedian Deconstruction. He's also one of the current iteration of David Lawrence's award-winning theatre company The Bacchanals and the host of two podcasts, my accomplice's The Witching Hours and his own big-book club The Year of Reading Massively (again, that voice). "He sets his own kind of path," Jerome offers.

Behind the mic, on his own path, Jonny's introduced audiences to a cluster of self-important men oblivious to their own ridiculousness: Richie Richardson in Skoolnite, Alan Legtit in The No-Nonsense Parenting Show, Stanley Mills in four-part podcast The Kincaid Weekender. He even revisited three of these men - Richardson, Legtit and Cool Youth Pastor - in his 2014 New Zealand Comedy Festival show, The Delusionaries. "What attracted me to those characters, to Alan Legtit and to Stanley Mills - in fact, to all of the characters in Kincaid Weekender - is that they made me angry," Jonny explains. "That sort of delusion and that perpetuating of that belief, or whatever belief they held, made me angry." Jonny's comedy is riddled with the neuroses of these men, egotists and hypocrites and bloody-minded cranks.

Loose is a bit of a detour from all that.

"I had a story about both booze and Iggy Pop."

In the textbook with all his cues, the story's called 96 - PASSENGER. It's from his second-to-last year at Wanganui Collegiate. The booze is gin, his introduction to heavy drinking; the song, Iggy’s iconic single 'The Passenger'.

"Iggy Pop is my favourite performer.” Jonny knows the man's work so well that, when a couple across the bar start sing-screaming the chorus to Kelly Clarkson's 'Since U Been Gone' (the Fringe Bar also does karaoke), he stops dead and tells me, very matter of fact, "This is an Iggy-type riff. It's a type of riff he's done."

It's a fundamental appreciation, one that runs much deeper than the kind of 'Fun House is probably my favourite album' surface-level affection people commonly feel for their favourite musicians (though Fun House is, in fact, Jonny’s favourite album). In 2013, Jonny wrote about Iggy for Wellington blog The Ruminator, a ‘review’ (it’s not) called 'Lost in the Fun House'. It goes some way to capturing the enormity of Iggy’s presence in Jonny’s mind.

When I’m doing stuff on stage though, it’s always Iggy. Not Olivier or Mingus or Lenny Bruce or some shit. Iggy Pop is my performance hero. There are people who are better at songwriting, singing, acting etc. etc. I don’t care. When I see Iggy Pop bark the ‘Swedish magazines’ bit in ‘Five Foot One’ on stage or hear the straight up SNEERING FUCKING MENACE on ‘Gimme Danger’… that’s performance to me. It’s an explosive consummation of talent, energy, daring, potential and it’s making me shaky just trying to tame all this into words on a screen. For my money, Iggy is it. Iggy is the pinnacle of performance.

Jonny tells me, "What I wanted to do, via the show, is elicit the same response from my audience that I get from Iggy." The project is loaded, for him. You can hear it in the way he draws out that sentence, his earnestness when he talks about how he responds to Iggy. Loose is enormous and intimidating and filled with expectation; it must be, for him to set his goal for it against a man whose sheer power makes him ‘shaky’.*

"I can't do and don't do what Iggy does," Jonny says, making sure I'm aware that I don't actually think he's trying to capture Iggy in a bottle. "So, I had to think about how I could get people to respond in a way that was almost visceral."

In that same Ruminator article in 2013, Jonny explains the dilemma.

If you do anything ‘creative’, you always have these ghosts around, trying to keep you in check. You invite them into your life, trying to incorporate and escape their influence.

Jonny's ghosts are the haunting type. His decision to start doing comedy the week after he returned from England in 2011 is intrinsically linked with to the comedians he saw in England, Josie Long and Sarah Pascoe and William Andrews ("who did this incredible fucking set with a balloon and Robbie Williams' 'Angels' and a camera on top of his head"). He talks about how, during his early gigs, he'd used to worry what Chris Morris, one of his all-time heroes, would think were he in the audience: "Would he be disappointed?" After the interview, he sends me a message on Twitter about the impact of Sophie Wu's Edinburgh Fringe Festival show Sophie Wu Is Minging, She Looks Like She's Dead("the biggest direct influence on Loose [and] the only one I saw twice in Edinburgh") and Jon Bennett's Fire in the Meth Lab.

During his early gigs, he'd used to worry what Chris Morris, one of his all-time heroes, would think were he in the audience: "Would he be disappointed?"

Loose is about ghosts, too, but not in a nostalgic way. His stories dwell on small signifiers, the kind that infiltrate your memory of a time, a moment, and colour it forever. A Converse billboard with Iggy's shoe size on it; a small, edgy pizza outlet in 1990s Kelburn; an oil landscape on a one-night-stand's bedroom wall. Little things that blow themselves up in your mind and frame your vocabulary. It’s in the title: A Private History. The meaning, first and foremost, is Jonny's.

A lot of those ghosts are non-human. One stands out above the others, though, both in the show and in the interview, due to the affection Jonny feels for it. "It's from going back there when I was 21. I got to walk around at night a lot there. When you walk around a place at night, deserted and shut down, you feel like it's your own. You feels it's yours." Whanganui. A featured player in the life of Jonny Potts. Jonny attended high school at Wanganui Collegiate, then moved back for a while in his early 20s. He talks about it like it’s the quintessential New Zealand town. And you can feel its influence on his later work, particularly Loose (for obvious reasons) and The Kincaid Weekender. "The air is different there, to me," he explains. "The quality of the light is different." He pauses. "It's just a fucking fairy-dust thing."*

In many respects, Loose is about breaking down the walls between Jonny and the audience. "I was aware that it was a departure. It had something in common with Let Us Reappraise Famous Men [Jonny's 2013 New Zealand International Comedy Festival show, in which he explored the lives and quirks of various interesting men, self-important or otherwise]. But even that show had barriers."

But Loose still exists within a framework, this one inspired by Oulipo, the 'workshop of potential literature'. Jonny specifically cites Georges Perec's A Void, a 300-word novel written entirely without using the letter e. Frameworks, like everything else, exist to restrain. ""There are better stories I could be telling, is the other thing. If I didn't have these constraints," Jonny stresses, each word enunciated like the business name at the end of an ad. ""There are bits where I'm kind of shoehorning one or other of the elements in."

Those structural limits aren't the only thing Loose exists within. It also exists within the context of modern stand-up, a context Jonny addresses in the way he talks about alcohol and sex, those worn stand-up staples. "I wanted to debloke down the 'pub-ising' idea of talking about booze," he says of the second element. "And the other thing was talking about sex without gloating about it or begging for it. Because a lot of stand-up is a man on stage talking about sex, and it can be...a lot of it's fucking horrible."

"This is no mission or anything," he adds, more to clarify the discussion than to deflect that idea. "It's not me going, 'I've got to stop this thing in comedy.' It's more, 'what if I didn't do it that way?' And then I'd say, 'what if I didn't do it that way,' and then another story would occur to me, and then--" Jonny cuts himself off.

He reframes the answer. "I made a promise to be honest,” he stresses. “Not thorough. Every story is honest, but not every story is the whole story. Because I like partial revelation." His voice goes softer on this, a comfortable and essential truth. "I like not knowing everything. And I think the audience knows enough about me that the stories make sense, without needing to tell them everything."*

"What do you do for a living?" The first minutes of Loose's return season. Jonny's doing crowd work.

His target responds, taking his time, "Electrician."

Jonny fires back, almost immediately. “Shocking.” Halfway through the word his delivery collapses, a pun made funnier for bailing out on it too late. It's like a building imploding while Yakkety Sax plays in the background.

"Loose was pretty tight by the time I got it up at the Fringe," he tells me later. "I tried to recreate what I had going into Fringe because I spent so long honing it down to what I thought was its essence. I think I got pretty close. And then I threw in maybe half a dozen jokes because I knew how the audience was responding to it." He mentions all this because he didn't write the show down, didn't video it, didn't play it for anyone prior to its opening night in the Fringe Festival. Jonny hadn't even done stand-up since a week in the Edinburgh Fringe Festival the previous August, opening for Jerome Chandrahasen. He trialled one of Loose’s pivotal moments by itself, in a converted children’s library in Edinburgh, standing on a pallet stage. "I got really worried about it," he admits while we’re at the Fringe Bar.

"But the coolest thing, on the last night of my show," Jonny adds, "there was a 21-year-old kid. As the audience started applauding at the end, he turned to my girlfriend and said, 'What a lovely man'."

"And that was...that was like..." Jonny tries to get the words together to describe this emphatic vote of confidence in Jonny Potts, Human Being. "A weird strike of validation."

"I suppose it's the mirror side of the other characters."*

"With comedians, there's a lot of personal investment. It isn't like, 'This is our theatre company, we can all absorb the blow.'” Jonny’s speaking to a specific experience here: in his 2014 Comedy Festival show The Delusionaries, he made a series of digs at Wellington theatre company Binge Culture. Twenty minutes after that show’s opening night, he performed at a Binge Culture Scratch Night. You wouldn’t expect it to be ‘water off a duck’s back’ if you went after a comedian like that, Jonny says.

But he’s also speaking generally, to the essence of comedy as an enterprise. “It's like, 'This is what I do and if you criticise it, it's an insult to me.'” He elaborates. “Mike Birbiglia has a line in Sleepwalk with Me, the show, where he says, ‘When an audience doesn't like you, they're saying, we don't like you. You know, your personality.’”

"With a comedian, it's often just a person on stage, and the audience verifying them or not."

The character Jonny brings to Dank Comedy Show is Riverman, his third outing to date. Riverman has been at the bottom of the Whanganui River for the last 150 years, but the Whanganui Tourism Board has dredged him up to answer questions - any questions - about "your next holiday destination!" He’s the ultimate manifestation of Jonny’s affection for Whanganui, an appreciation that recognises the received wisdom of Whanganui being boring, shabby and a little bit racist, and powers on through it.

"I did actually go down to Moutua Gardens at the time of the occupation in '95," he recalls, referring to the 79-day protest action taken by Whanganui Māori. The Gardens, on the bank of the Whanganui River, were the site of a pā; local Māori argued that land had been exempt from the purchase of Whanganui, and came to blows with the Council over the issue. "I feel so much more in tune to the people than I do anywhere else," Jonny continues. "And I don't even know much about the history of the place. Comparatively."

(A week after Jonny debuts this character, the New Zealand Improv Festival programme is released. In it, Riverman is part of a double-bill with Melbourne improvisor Rik Brown.)

Riverman's grand, expeditionary accent rolls out over the crowd. "QUESTION?" One punter rises to the call. "How big and deep is the Whanganui River?"

Riverman pauses. "Sir," he throws back. "How big and deep is your love?"

LOOSE: A PRIVATE HISTORY OF BOOZE & IGGY POP 1996-2015

is on at 505@5 Eliza St

8-13 September

Tickets available here