Invisible and Indivisible: Going Beyond the Exhibition

Chloe Geoghegan shines a spotlight on New Zealand's role in depleting the Western Sahara desert through the practice of Matt Galloway.

Chloe Geoghegan shines a spotlight on New Zealand's role in depleting the Western Sahara desert through the practice of Matthew Galloway.

The lion slumbers in his lair,

The serpent shuns the noontide glare:

But slowly wind the patient train

Of camels o’er the blasted plain,

Where they and man may brave alone

The terrors of the burning zone.

— Felicia Hemans, Sahara, The Caravan in the Deserts

For as long as I’ve known Matthew Galloway, themes of navigation and discovery have driven his practice. Primarily: way-finding, dispersion, distribution, redistribution, disappearing and reappearing have given his work in the field of graphic design, and more recently exhibition-making, a very literal sense of direction. While it is easy for a graphic designer who has been captured by the artist community to deploy these notions as a bridge between the art world and its audience, Galloway’s practice has recently begun to move beyond these bounds.

In the past, Galloway has used these interests to engage in local communities and find new ways to challenge collective perception. His self-published bimonthly local newspaper The Silver Bulletin (2011-2012) brought the Christchurch arts community together during a citywide counter-productive malaise after the earthquakes. For readers and contributors alike, The Silver Bulletin became an underground symbol that offered a sense of direction, a way to recalibrate our spinning inner compi and maintain criticality and independence through a dearth of gap filling.

An early issue of The Silver Bulletin themed ‘way-finding’ sought to map the image of Christchurch more cognitively than physically. Galloway explained in his editorial that architect Kevin Lynch first used this term in his 1960 book The Image of the City when theorising “the image”. He wrote that the image is an in-built way-finding system based on memory and individual perception, stronger than outside devices such as street numbers or road signs.

This preoccupation with the image often brings Galloway to the work of Seth Price, artist and the author of cult handbook How to Disappear in America. In his 2002 essay “Dispersion”, Price theorises that when dispersed and reproduced, a work of art reaches a value of zero as its accessibility rises, due the plasticity of contemporary networked life. He argues that collective experience is based on simultaneous private experiences, distributed across the field of media culture, woven together by ongoing debate, publicity, promotion and discussion. In her 2008 Freize review of Price’s solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Zürich, Polly Staple exposes a meta or self-reflective narrative to Price’s work that circles around the meaning of an exhibition. It reminds me of how Galloway often uses exhibitions and publications to process and think through the image. She writes:

The exhibition’s role as a knowledge-producer, say, or the artist’s role as deliverer, or rather perhaps distributor, of information and illumination – itself becomes a self-consciously discursive point of contention and engagement.

The exhibition as a method for the dissemination of knowledge has become a significant part of Galloway’s practice, and has recently lead him to one of the most remote areas on earth: a refugee camp in the middle of the Sahara. With this project, there is a real sense of before and after. Before Galloway’s journey, several iterations of the exhibition The Ground Swallows You embodied a sense of distance, of not quite having all the pieces of the puzzle. As Time Goes By, produced in the camp and reproduced after at The Dowse, is less speculative and more precise. Having witnessed a confusing reality that is so distant but so shockingly connected to our own, Matt reaches beyond processes of knowledge dispersion and distribution, leaving the viewer with a single, powerful image that captures everything the following complicated story has to offer.

* * *

When I met with Galloway last year to discuss the development of The Ground Swallows You, he had been following a container ship after noticing it docked at the Ravensdown factory in Dunedin, across the harbour from his house. One of thousands of bulk carriers moving on an endless global conveyor belt, Galloway had witnessed a fleeting moment that exposed free market capitalism, history’s most sophisticated distribution system to date.

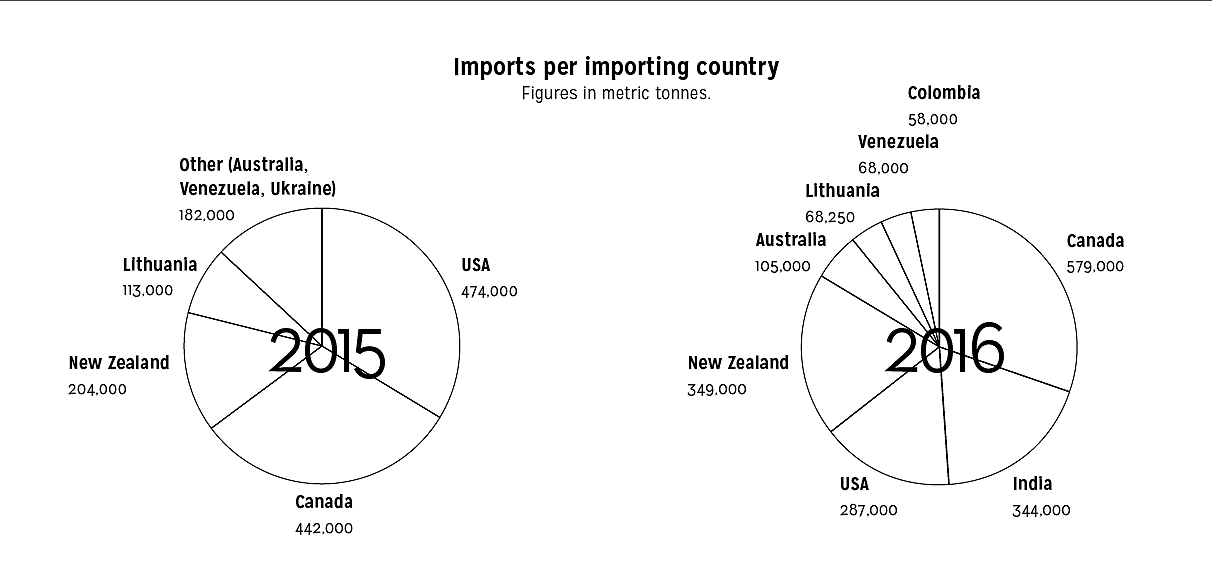

Sitting in open-top containers, tonnes of dusty orange-yellow desert sand were being unloaded onto the dock. All the way from Western Sahara in North Africa, this foreign desert rock contains high levels of the chemical compound phosphate and is one of the most valuable and quickly depleting resources on earth. Estimated to run out in less than half a century, New Zealand is the second largest importer of phosphate rock from Western Sahara in the world.[1] According to company Ballance Agri-Nutrients, New Zealand needs phosphate rock to produce the fertiliser ‘superphosphate’. Having set the pace for agricultural development since it began coming into the country in 1878, 180,000,000 kg of superphosphate is spread across New Zealand annually.[2]

Unlike the Sahara, pasture is the dominant land cover in New Zealand. Because Indigenous forest cover has been reduced from 85% to 23% since colonisation, the fragile ecosystems that keep our drinking water clean have been severely altered with 60% of New Zealand’s rivers and lakes now unswimmable.[3] In some instances, nitrates can take decades to leach through the ground and emerge in surface waters. But in areas such as Lake Rotoiti and Lake Rotoehu in the Bay of Plenty, harmful blooms of toxic algae can develop quickly. With an estimated 6.6 million cattle now grazing, urinating, defecating and trampling across New Zealand, concern for water quality is high.

Social and economic factors related to growth are complex contributors to this issue. As well as more mouths needing to be fed, New Zealand maintains a high standard of living assisted by earnings that come from exporting agricultural products. With ‘peak phosphate’ expected to occur in the coming decades and no synthetic alternative, major policy changes need to be made from above that do not come at the expense of our own natural resources, and that of others. Because as it turns out, obtaining that orange-yellow mineral-rich dirt that enables New Zealand’s intensive agricultural practices is also, as Galloway discovered, a catastrophe for the people who rightfully own it in North Africa.

* * *

After presenting The Ground Swallows You at Blue Oyster and then at Artspace, Galloway was selected to participate in After The Future, the tenth edition of ARTifariti: the International Art and Human Rights Meeting in Western Sahara. Held annually within the Sahrawi refugee camps on the border of Algeria, ARTifariti invites participants to produce and present work for exhibition in and around various buildings across several of the camps. Structured into several different exhibitions and events, this 10th edition of the meeting exhibited 58 local and international artists including 14 Sahrawi collectives. While artists were invited to create work specific to the contexts of the camps, they were also encouraged to think globally around the issue of postcolonial conflict and to imagine what the future may hold for youth caught in the struggle for self-determination.

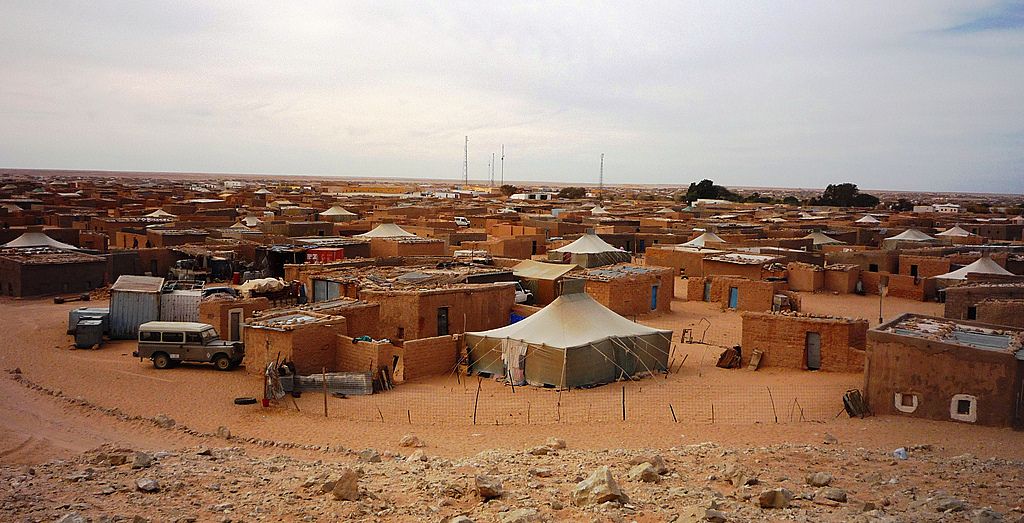

With a suitcase full of work Galloway flew from Dunedin to Auckland, to Dubai, to Madrid, to Algiers. There, he joined about 40 fellow participants from around the world (artists, curators, journalists, humanitarians) on a domestic flight across Algeria to the western most edge of the country. After landing at a one-room airport in the desert town of Tindouf, the group took a convoy of Jeeps for several hours into the desert, stopping and starting at various check points to arrive at the Sahrawi refugee camps near the border of Western Sahara – their temporary home for the next 15 days. Here, Galloway would present As Time Goes By, a kind of sequel to The Ground Swallows You that originally explored the issue from a New Zealand perspective.

The Sahara is one of the least populated places on earth. In his essay, In the Desert, with Peace, Galloway describes the scene that greeted him when he awoke in the desert:

With only the sound of the curtain flapping about in the desert wind, he goes on to describe how an alarming feeling of foreignness came across him. The blur of travel was now behind him and he realised he had been transplanted somewhere that couldn’t be further from where he had come. “In that moment, any remaining sense of poetry or abstraction I still had [about this place] was broken up and reformed into a new understanding of reality; as if a dark spot in my mental image of the world had just been illuminated.”

The situation in Western Sahara is as complex as all humanitarian crises around the world. What gives it a macabre edge on most is how long the current battle for this arid land has been raging, and how invisible it has become.

The situation in Western Sahara is as complex as all humanitarian crises around the world. What gives it a macabre edge on most is how long the current battle for this arid land has been raging, and how invisible it has become. The Latin word for desert, deserere, means to forsake, abandon or give up. Desert also means to leave, quit, depart and let down. This area of the world has come to embody this term that outsiders have applied to it, with the Spanish maintaining a presence in the territory since the fifteenth century, fishing in the surrounding Atlantic and launching slave-hunting missions from the Canary Islands.[4] While outsiders call this territory a desert, the Moroccans across the northern border call it Blad as-Siba, land of dissidence. In the early centuries Indigenous nomadic groups in this area flourished as raiders and were far more powerful than their sedentary, urban neighbours in Marrakesh or Timbuktu. For Sahrawi nomads, the land was ample pasture. They were people who left no mark on the land, no mines, no cultivated fields.[5] This lack of damage has meant these people are now victims of the lightness of their own footprints, as outsiders struggled to pin ownership of natural resources to one group or community in the ways that make sense in a modern world. Today, Western Sahara is one of the very few remaining non-self-governing territories in the world, commonly described as the world’s last remaining colony.

The origins of the current dispute for this territory can be traced back to 1975 when Moroccan forces invaded Western Sahara after the Spanish decolonised the region. Sahrawi liberation group the Polisario Front fought the invasion through combat, ending in a 1991 ceasefire, brokered by the UN with the promise of an independence referendum that never came. Continued resistance has moulded a Sahrawi political identity that has collectively developed a capacity to endure war, landmines, napalm drops, abductions, beatings, torture, starvation, and confinement from Moroccan forces. While the Kingdom of Morocco’s claim over the territory is considered illegitimate by the International Court of Justice, the ‘patriotic zeal’ of the Alaouite dynasty’s continued campaign has lead Moroccans to see the territory as not only as reclaimed historical land but an essential source of economic glory and a tourist Mecca. Attracted by the strong Atlantic winds, wind-surfers travel to the territory to holiday as well as compete in international events. In 2015, Richard Branson’s Virgin group controversially sponsored the Kite Surfing World Cup in Dakhla, not far from an absurdly long, 2 metre high sand wall designed to withstand Polisario forces – fortified with approximately 5 million landmines and guarded by 120,000 Moroccan soldiers.

The Moroccan royal family have also launched an enormous self-owned wind turbine initiative across the disputed territory: 40% of Morocco’s wind production and 95% of the power supply needed for phosphate mining. This entry into the lucrative renewable energy industry is awash with misleading marketing, claiming at the 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference (ironically held in Marrakesh) to be green “solutions” powered by “Southern Morocco”. Developing the territory in this way has caused an uproar from activists, who claim that Morocco is now bringing their illegal and brutal occupation of the land up two fold, literally cementing their claim through investments and development.

* * *

Described by Manuel Herz, editor of From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara, as heterotopias or proto-cities, the series of camps established along the Algerian border are in a part of the Sahara considered so inhospitable it is known as ‘the Devil’s Garden’. Forced to flee their homes and abandon their nomadic way of life, living in the camps has assisted in the Sahrawi tribes uniting to create a single national identity. Even though daily existence is measured by litres of water and calories consumed, like many long-term refugee camps around the world, these camps now contain schools, medical centres, markets and recreation spaces – all defining a social order among a nation of refugees. This urbanised space that only exists as a reaction to violence, conflict and suffering has managed to avert the emergency in such a way that it has become invisible internationally. As Herz explains: “Instead of solving the Western Sahara conflict politically, camps are being built.”

While in the camps, Galloway tried to picture what it must be like to exist without the feeling of peace he experiences at home:

This atmosphere of suspended tension that Galloway was able to glean from life in the camps was exactly what the four curators of ARTifariti wanted participants to feel. Sahrawis UmdLaila Bujari and Walad Mohamed along with Spanish nationals Charo Romero Donaire and Jose Iglesias Gª-Arenal used After the Future to argue for the generation of Sahwari youth born after 1991 that have grown up in the camps after the war and ceasefire. In constant suspense due to the delayed referendum, this is a generation that has never set foot on the land they are forever fighting for. Even though they have never been able to vote, they live with the notion that someday they could, if they keep fighting for it. The curatorial statement for After the Future captures this permanent anxiety:

The concluding exhibition at ARTifariti created a network of solidarity that moved beyond borders, sand walls, international policy and diplomatic promises. While After the Future was an opportunity to capture the precariousness of the future, it also exposed the limitations of the present. In conversation with Galloway about the exhibition, it became clear just how difficult it was to organise and create a site for dialogue and production inside a refugee camp that borders a conflict zone. Unable to travel into the region with cameras or any large equipment, sharing and using what was available contributed to more light weight, ephemeral displays.

The work Galloway exhibited at ARTifariti titled As Time Goes By, consisted of three large black and white fabric banners hanging on the outside of a mud brick building in a public square. The illustrated words “As time goes by” in English and in Arabic surround the central image of a bird – unmistakably the now defunct but iconic Ravensdown logo. The bird evokes the image of a peace dove but instead of an olive branch it carries a portion of another logo made up of a strand of wheat – part of the OCP Group logo – Morocco’s phosphate company. Using these symbols as a new visual language with which to create meaning,[6] this image is the antithesis of peace and represents New Zealand’s invisible but indivisible relationship with the Sahrawi people. Through the importing of phosphate from the illegally held territory, New Zealand sustains its intensive agricultural industry and supports the ongoing oppression of the Sahrawi people. Flapping about in the desert wind, these three flags simply and effectively connect the many dots described in this essay, revealing a compelling, complex and confusing narrative that has unravelled a little more every day since Galloway first noticed the container ship docked in Otago Harbour.

Galloway’s position within this swirling nexus of dots, maps, images, symbols, people and politics is, without a doubt, one of ideological engagement and personal consequence. By using the image as an act of solidarity and participation, he unmistakably takes cue from the way Hito Steyerl connects war and art museums to expose a series of interconnected, paradoxical narratives that implicate corporations, governments, cultural institutions and innocent communities. In today’s complicated world of hegemonic complacency and overwhelming precarity, many artists have chosen to move away from elite audiences and into direct political action that looks outward to whole populations.[7] In Ekaterina Degot’s e-flux essay A text that should never have been written? she reminds us that the relatively safe common ground of contemporary art is shifting.

Degot’s essay features in Joanna Warsza’s 2017 publication I Can’t Work Like This, A Reader on Recent Boycotts and Contemporary Art, which demonstrates a cultural shift, whereby artists are almost continually confronted with political dilemmas and must choose to engage or disengage. While artists have used their practices to speak out over objectionable circumstances for many decades if not centuries, Warsza’s reader exemplifies a current a moment where contemporary practice as a whole seems to be shifting to a more outward position as demonstrated by Steyerl.

* * *

Currently on display in ST PAUL St Gallery’s ‘Frontbox’ window space until February, As Time Goes By addresses not only a new generation of Sahrawi that have experienced the conflict differently to anyone else, but also a new generation of New Zealanders that are searching for a more transparent and environmentally friendly Aotearoa. Speaking from Sydney, Kamal Fadel, the Polisario’s Australia and New Zealand representative, is optimistic that the new New Zealand government can make one simple and immediate decision to halt the illegal importing of phosphate and become a leader in efforts to resolve the crisis. Fadel emphasised that the law is very clear and on the side of the Sahrawi people. Fadel’s stance started to seem more realistic earlier this year when 54,000 tonnes of phosphate (one eighth of New Zealand’s annual needs) was seized in South Africa while refuelling on its way to New Zealand causing panic at Ballance Agri-Nutrients who were receiving the shipment. Still awaiting a decision by the courts in South Africa as to who rightfully owns the phosphate (OCP or the Polisario), there have been calls to start looking elsewhere for the resource if the conflict begins to escalate again. With so many young Sahrawi growing impatient to reclaim a land they have never seen, there is every chance the Polisario could begin to take further action, whether that is stopping more shipments or restarting military action in the region.

In contrast, most farmers in New Zealand are simply not aware of the situation because of misleading reassurance from their cooperatives, and it being so far from their everyday reality

Together, Ballance Agri-Nutrients and Ravensdown supply 98% of all fertiliser used in New Zealand. Ravensdown argue that the group of Saharawi still inside Western Sahara benefit from their purchase of phosphate. Acknowledging there is a larger group of Sahrawis over the border not benefitting, they are “not convinced that the actions of two farmer-owned co-operatives on the other side of the world will change a 40 year-old political stalemate that the UN has so far failed to resolve.” They also argue that “without phosphate fertilisers, New Zealand rural production would fall at least 50% which equates to a $10 billion per year hit to the economy.” However this argument is disputed by groups such as the Norwegian Council on Ethics, who confirm that it is feasible to produce fertilisers without buying phosphate from Western Sahara, and that Australian company Wesfarmers Ltd has pledged (but not yet acted) to make the necessary changes to reduce its dependence on phosphate from Western Sahara[8]

Because New Zealand’s fertiliser industry is made up of cooperatives of independent farmers, it has been difficult for activists to gain any momentum in New Zealand, as overseas companies which have stopped buying Western Saharan phosphate rock have mainly been forced to due to the institutions financing them being pressured to divest. In contrast, most farmers in New Zealand are simply not aware of the situation because of misleading reassurance from their cooperatives, and it being so far from their everyday reality. What they are aware of, however, is mounting pressure from the likes of media, scientists, researchers and agribusiness consultants to increase sustainable farming practices to improve water quality. If New Zealand is able to take steps to assist in resolving the Sahrawi crisis and reduce its heavy reliance on phosphate, not only will our own ecosystem begin to restabilise, but our food choices and our economic power and freedom will no longer come with an abusive price tag.

In May 2008, in her position as President of the International Union of Socialist Youth, our new Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern travelled in a delegation to the Sahrawi camps. One of the few New Zealanders alongside Galloway who have seen the camps, she has used this experience to argue for increasing refugee quotas rather than critiquing New Zealand’s economic involvement in the crisis and its environmental impact on our own soil. For this essay, I put the question of our nation’s stance to Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters. In his signed letter of response on 30 November 2017, he confirms the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade are satisfied to continue the status quo:

New Zealand recognises the 2002 United Nations legal opinion on the question of natural resources and its stipulations about the need for the Sahrawi people to benefit from any resources extracted from the Western Sahara. New Zealand companies importing phosphate from Western Sahara have advised that they are doing so in accordance with international law.

Not only is this statement frustratingly paradoxical, it also brings up the question of benefit. Instead of inquiring as to who is and isn’t benefiting from importing phosphate from a disputed territory, the government rests compliantly within an unethical cycle of assurances from the New Zealand companies Ravensdown and Ballance importing phosphate and the Moroccan company OCP exporting it.

* * *

Having been back in New Zealand for a year now, Galloway has continued to explore the issue and its many facets through exhibiting and distributing publications in a range of exhibition spaces both here and abroad. Recently, the project has been exhibited in Spain at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León and in Argentina at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo del Sur in Buenos Aires – both part of group exhibitions supporting and exploring the Sahrawi campaign. What began as a graphic enquiry into the geopolitical implications of shipping on the high seas has gone beyond the traditional parameters of an exhibition, becoming a part of a movement toward action through artistic production and distribution.

The Ground Swallows You and As Time Goes By have both invited the viewer to dive into the black hole that this multi-layered issue creates and empathetically question New Zealand’s economic reliance on exploiting a disputed territory. In the way that Seth Price’s work turns on a narrative reflecting on itself, so too does Galloway’s. By building a narrative of production and consumption, value and meaning, strategy and reference, he blends critical discourse with acts of solidarity through distribution and production of an image inside and outside of gallery spaces.

In this era of slow apocalypse, where it often feels like we are living in a science fiction story that we are all writing together, it is all the more important to recognise that ‘wallpaper issues’ such as Western Sahara’s forgotten crisis form deep layers within our collective narrative. Because our government and major corporations continue to overlook our pivotal position within this crisis, New Zealanders are unconsciously participating in a global economy that functions to benefit some while exploiting others.

If New Zealanders, from those purchasing phosphate rock from behind their desk, to those grabbing a bag of superphosphate at the garden centre, and everyone buying groceries at the supermarket, can break down the image of the world as an immovable, implacable place, perhaps we would begin to implement change that will soon be essential to our own existence as well as that of others.

As Malcolm Gladwell identifies through the theory of the tipping point, we must reframe the way we look at the world if we are going to make any kind of exponential change. “We throw up our hands at a problem phrased in an abstract way, but have no difficulty solving the same problem rephrased as a social dilemma.”[9] If New Zealanders, from those purchasing phosphate rock from behind their desk, to those grabbing a bag of superphosphate at the garden centre, and everyone buying groceries at the supermarket, can break down the image of the world as an immovable, implacable place, perhaps we would begin to implement change that will soon be essential to our own existence as well as that of others. To alter our world view in this way might bring us closer to the mindset of a Sahrawi nomad: dispersed, moving and circling all the time; way-finding with no fixed point on a map to grind down or leave lasting impressions upon.

The goal of civilization is sedentary culture and luxury. When civilization reaches that goal, it turns toward corruption and starts being senile, as happens in the natural life of living beings.

—Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah (1377)

You can grab a free copy of The Ground Swallows You Parts 1 and 2 from: ST PAUL Street Gallery, Artspace, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, The Physics Room and Blue Oyster Art Project Space.

[1] In 2007, at the current rate of consumption, the supply of phosphorus was estimated to run out in 345 years. Michael Reilly, "How Long Will it Last?" in New Scientist 194 (2007): 38–9.

[2] Stephanie Parkyn and Bob Wilcock, “Impacts of agricultural land use” in Jon Harding, Paul Mosley, et al., Freshwaters of New Zealand (Christchurch: New Zealand Hydrological Society and New Zealand Limnological Society, 2004), 34.2.

[3] Ibid., 34.1.

[4] Nicholas Jubber, The Timbuktu School for Nomads: Across the Sahara in the Shadow of Jihad (Boston: Nicholas Brealey, 2016), 110.

5. Ibid., 108.

[6] Melanie Oliver, This Time of Useful Consciousness: Political Ecology Now (14 April – 30 July 2017), The Dowse Art Museum.

[7] Gregory Sholette, “Art Out of Joint, Artists’ Activism Before and After the Cultural Turn” in Andrew Ross, ed. The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labour (New York: OR Books, 2015), 85..

[8] Gro Nystuen, Andreas Føllesdal, et al., Phosphate Recommendation, Council on Ethics, Norway (2010), 19.

[9] Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2000), 257.