Museums, Non-Neutrality and Writing Histories: An Interview with Sean Mallon

Lana Lopesi talks to Sean Mallon about the responsibilities and privileges of writing Pacific history as Te Papa’s Senior Curator Pacific Cultures.

Lana Lopesi talks to Sean Mallon about the responsibilities and privileges of writing Pacific history as Te Papa’s Senior Curator Pacific Cultures.

“Museums are not neutral” reads a t-shirt which hangs over a colleague’s chair in Sean Mallon’s office. The t-shirt is a collaboration between LaTanya Autry (cultural organiser/curator/art historian) and Mike Murawski (Director of Education and Public Programs, Portland Art Museum) who, through the #MuseumsAreNotNeutral campaign, are combating the ways in which museums “embrace the myth of neutrality.” The campaign encourages museums to not see themselves outside of political and social issues; Autry and Murawski believe in the transformative potentials of museums and their ability to be agents of positive change.

The term museum derives from the Greek term mouseion, which translates as a shrine to the Muses, the nine goddesses of the arts and sciences. In Roman times, a museum was a designated philosophical institution or a place of contemplation, placing it more in line with a contemporary university than anything else. The word museum than reappeared in 15th-century Europe to describe the collection of Lorenzo de’ Medici. In this usage, the term referred to the comprehensiveness of the collection itself, and by the 17th century the term was being used across Europe to describe collections of curiosities. During the 18th-century Enlightenment period, with increased world exploration and growing interest in foreign treasures and knowledge production, the British Museum in London opened, soon followed by the Louvre in Paris. This British government accepted responsibility to preserve and maintain collections, and set the premise of the British Museum to be “not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public.” These two institutions and their public-facing model form what we know today as the contemporary museum; this national museum model has since been adopted worldwide including here at Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand.

Mediating a public understanding of histories – through the collections – is then arguably the key function of the contemporary museum. However, the #MuseumsAreNotNeutral campaign reminds us that the ways in which we frame and articulate histories, especially within national museums, needs constant evaluation. The idea of museums not being neutral – that museums are manifestations of people’s biases and subjectivities – is perhaps an obvious statement to make within the GLAM sector (galleries, libraries, archives and museums). But for the general public, it becomes easy to assume you are looking at a whole picture, a truth – as the museum does not often highlight its own blind spots or contradictions, although this seems to be a changing practice.

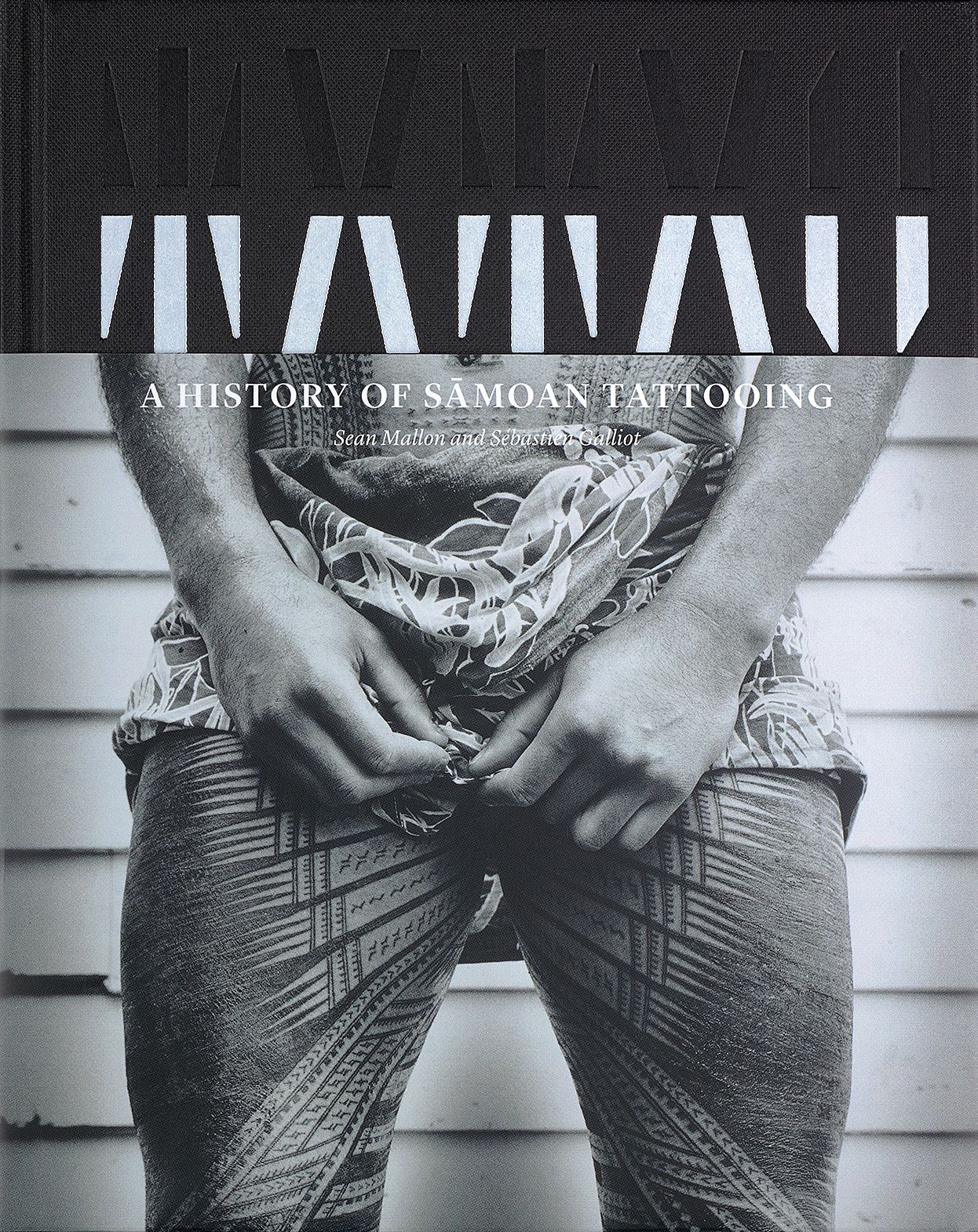

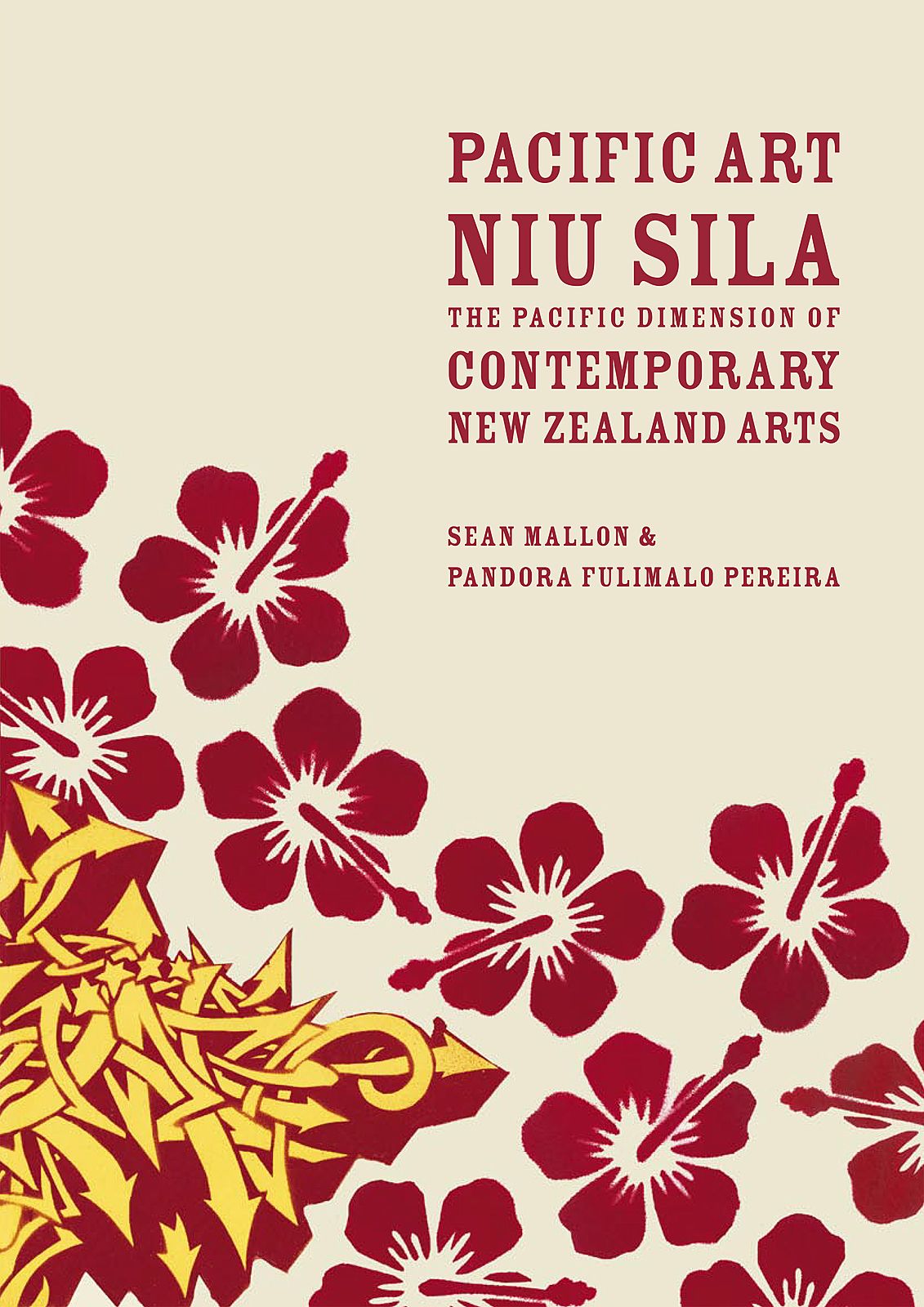

National museums in this sense don’t only display national histories but they write them too. In Aotearoa, Te Papa Press plays a key role in the production of historical texts and is arguably one of the most important producers of texts relating to Pacific histories in Aotearoa. Speaking in Colour: Conversations with artists of Pacific Island heritage (1997) and Pacific Art Niu Sila: The Pacific Dimension of Contemporary New Zealand Arts (2002) are still today two of only a handful of texts on Pacific art history in Aotearoa. Similarly, Tangata o le Moana: New Zealand and the People of the Pacific (2012) is the first illustrated history of Pacific experience in Aotearoa, and again is a pretty unique text within Aotearoa. Now a new book has been released titled Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing which is another ‘first’ for Te Papa Press, this time being the first book to significantly look at 3000 years of Sāmoan tatau.

What all of these books have in common, or perhaps whom they all have in common, is Sean Mallon. Mallon is currently the Senior Curator Pacific Cultures at Te Papa, however started at Te Papa in 1992 on a two-year collection management internship and between then and now has held a number of roles. When Mallon entered curation he and Fulimalo Pereira were the “first trainees of Pacific Island descent to enter the curatorial field at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Auckland Museum respectively.” In that time, with his colleagues, he has actively written and exhibited previously sidelined histories, those of Pacific peoples in Aotearoa.

When I heard about Mallon’s latest book Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing, co-written with Sébastien Galliot (with many other contributors also included), I felt both relieved that such a history was being written but also anxious about a history becoming fixed. For many Sāmoans, tatau is something that people have personal relationships with and also strong ideas about, which in many instances are contradictory and clashing – a complexity that has been excellently captured through the text. The weight of a cultural practice like tatau made me think about the absolute privilege curators have to set these historical narratives but also the responsibility that comes with that. So, on this occasion I took the chance to ask Mallon some questions about what it means to write history, acknowledging our own subjectivities and asking where to from here.

*

Lana Lopesi: What does history mean to you?

Sean Mallon: History means a great deal to me, we can learn from history, from what people have done, thought and said, from what they have experienced. I am interested in how we can analyse historical events or sequences of events to learn more about the past as well as the present. Working in a museum there are many opportunities to do this and explore the significance of history with other people.

LL: How do you place yourself in a history?

SM: I am a participant and an observer, but as my history curator colleague Kirstie Ross has said, “We are least observant of our own history.” I want to work on this…

LL: How do you negotiate Pacific history, within New Zealand, and within a national museum?

SM: Negotiate is a good word to describe how we approach history in the national museum. We are constantly negotiating the kinds of conversations we want to have and the types of interventions we aspire to make. As curators, we don’t all approach history in the same way, we come from different social and cultural backgrounds, we have different experiences, academic training and perspectives. I’m trained in anthropology and bring a tool kit representing my interests and learnings in the discipline to the role. As someone responsible for bringing Pacific perspectives to the national museum, a continuous thread in all my work is finding ways to interrogate or disrupt the dominant narratives. When it comes to the grand narratives of New Zealand history, Pacific peoples’ experiences are underrepresented – how can I work with and against these narratives to bring Pacific peoples’ stories to light and reshape the narrative?

LL: I’m interested in your use of grand narratives here, which raises to me the priority of a colonial and Western-dominated history of nationalism. Could you define three characteristics of “the grand narratives of New Zealand history”?

SM: You are more precise here than I have been. You’re right, it is the colonial and Western-dominated narratives that I am interested in unravelling and re-braiding – in particular the dominance of the idea of ‘the nation’ and ‘national identity’ in New Zealand history writing. The work I did with Kolokesa Uafā Māhina-Tuai on the exhibition Tangata o le Moana: The story of Pacific people in New Zealand (2007), followed by the collection of essays we edited a few years afterwards (with historian Damon Salesa, 2012) were an attempt to reshape and reframe some of these dominant narratives. Around the same time, the present generation of New Zealand historians was also occupied with reframing New Zealand’s history ‘beyond the limits of the nation-state’ and they went some way to demonstrate this in the New Oxford History of New Zealand (2009). Damon was a contributor to that volume.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, New Zealand histories in print barely referenced Pacific peoples at all. For example, you’d struggle to find an indexical reference to Pacific peoples in relation to the First and Second World Wars even when Pacific Islanders were part of New Zealand’s armed forces, and the emphasis (if there was one it was minimal) on the arrivals of Pacific people in New Zealand was restricted to the post-Second World War period – when Pacific people had been continuously coming to New Zealand for over 1000 years. In simple terms, three ways we wanted to rework the dominant narratives of New Zealand history involved: 1) Putting New Zealand in the context of the Pacific and thinking about New Zealand as a Pacific place. 2) Acknowledging a much longer history of Pacific peoples coming to New Zealand that didn’t begin in the post-war period. 3) Recognising the ambivalence New Zealand society has had towards Pacific peoples, and what this means for contemporary New Zealand and its future.

Curating the exhibition and publishing Tangata o le Moana, and just thinking about New Zealand as a Pacific place, felt like an intervention in the historiography, a precedent to the lively discussions around Damon’s hard-hitting book Island Time (2017), where he expands in depth on similar themes.

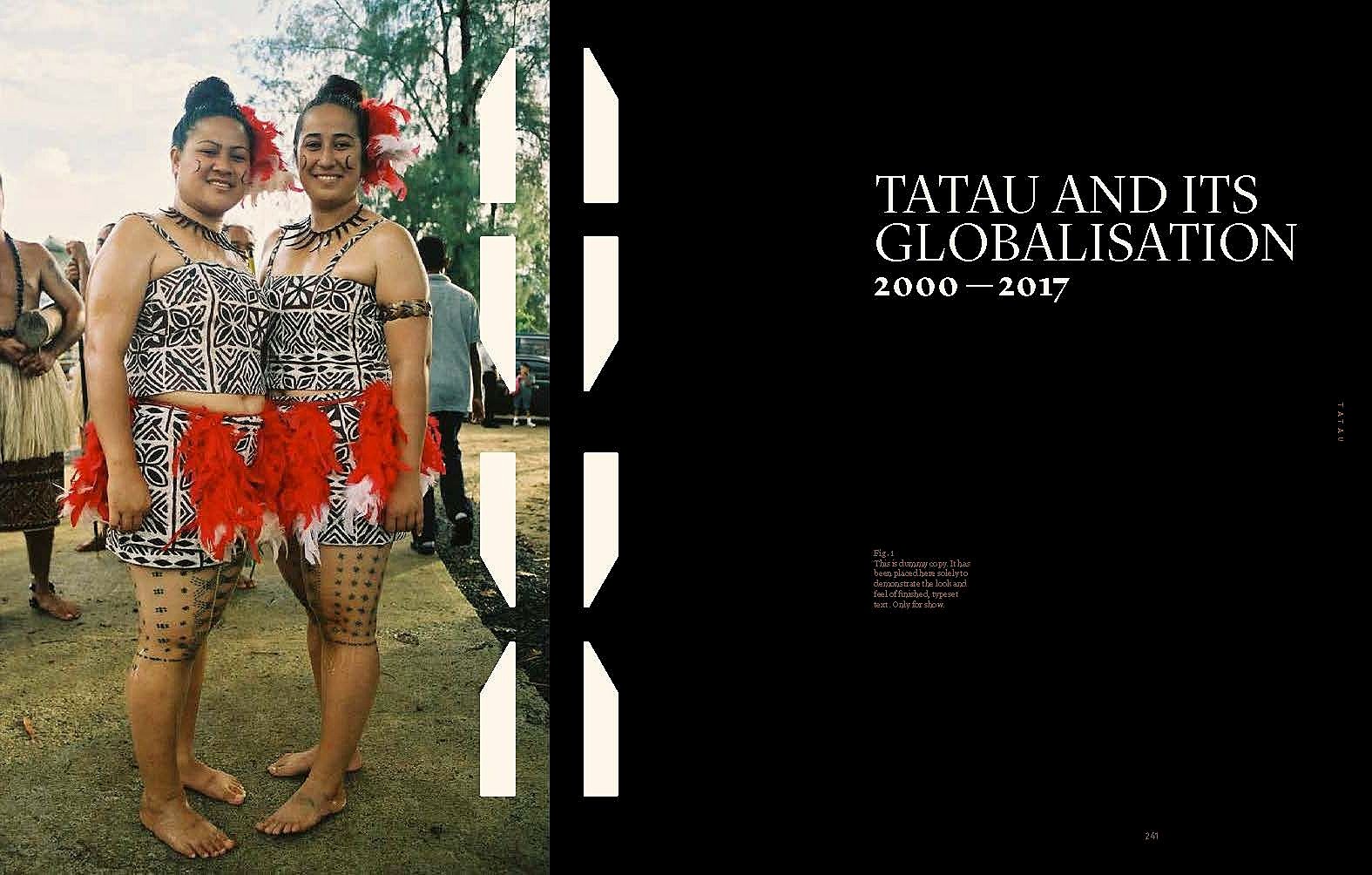

LL: Tatau is something Sāmoans hold very close and revere but also has potential to divide people, how do you even began to approach that kind of subject matter historically – a subject which is still, and arguably always will be, in flux?

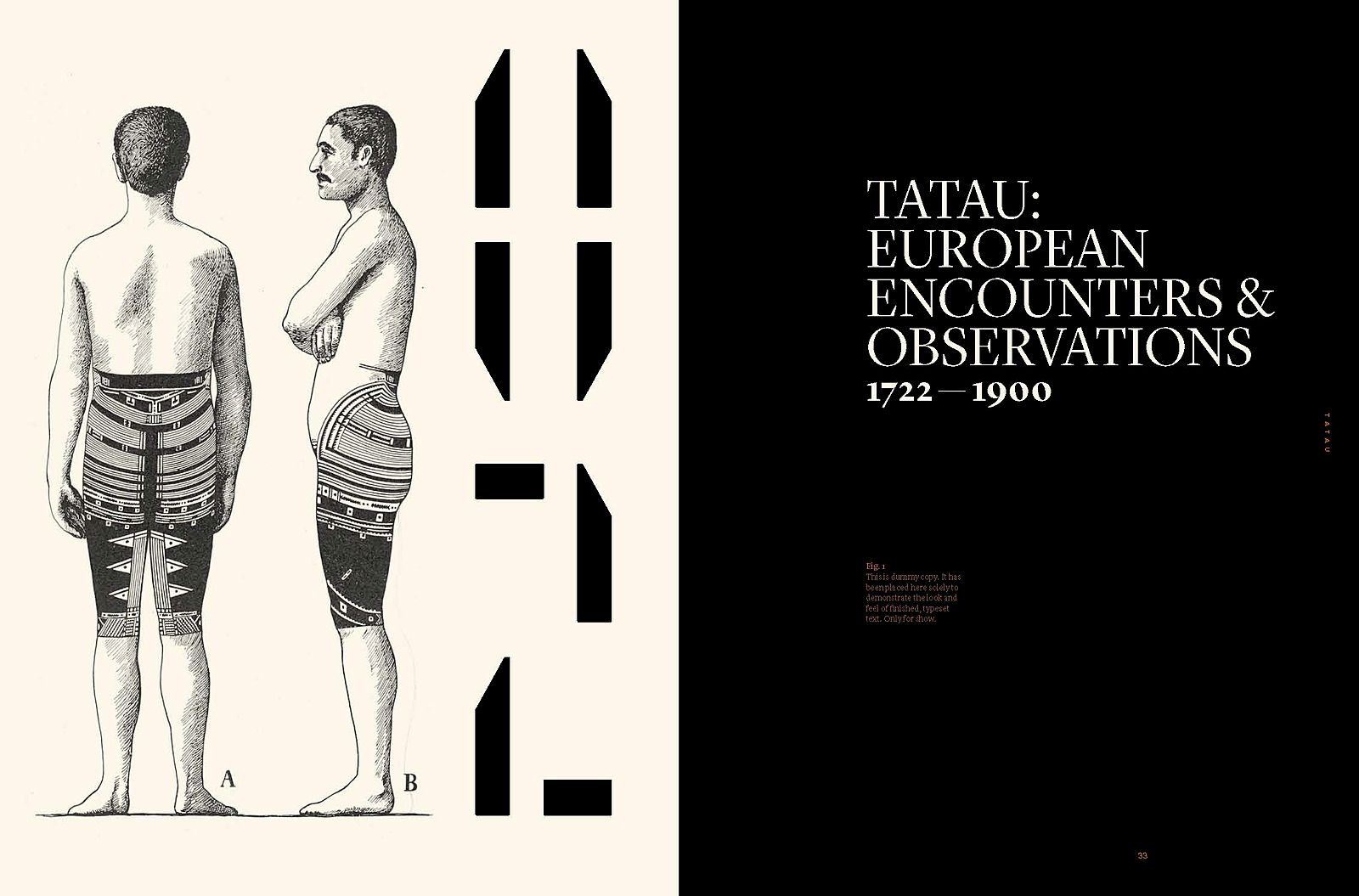

SM: My co-author Sébastien Galliot and I have called our book Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing because we want to acknowledge that this book is exactly that, A history – not THE history. It’s not the final word on tatau. It is one of a range of possible narratives, just one version of a story. When you talk about how to begin to approach this subject matter historically, our approach was to look for archival materials in museums and libraries, for observations and writings, records and oral histories. We examined how tatau has been depicted in drawings, photography and film. We followed tatau where it has travelled on peoples’ bodies, through time and across the world. We looked for objects associated with tatau that have ended up in museums and private collections – these ranged from tattooing tools, to t-shirts, to tattooed skins. We thought about how people talk about tatau online, the images they post on Facebook and Instagram. Following tatau across multiple sites or locations involved visiting and interviewing people, developing relationships and attending tattooing conventions. It has even involved getting tattooed.

the history of tatau we have put together emphasises both continuity and disruption

One of the stereotypes associated with tatau is that knowledge of the practice and the meanings of its designs is handed down intact and unchanged from generation to generation. But the history of tatau we have put together emphasises both continuity and disruption, with social, cultural and technological change in tatau coming from within Sāmoan society as much as from the outside world. It is true as you say, that the topic of tatau has the potential to divide people, but so does the history the Tama’aiga, the fa’amatai, religion in Sāmoa and possibly almost any other aspect of fa’asāmoa you care to name. I hope with Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing we have been able to highlight how Sāmoans (and not just the tufuga) have made tatau a contested practice, and one where they have been active participants in its making and remaking.

Another feature of the book is the shorter contributions from other writers. We were interested in creating a multi-vocal text drawing on other people’s experiences and expertise related to tatau. It was an opportunity to share the storytelling around a little bit.

LL: Multiplicity and multiple voices seems to me much more simple as an idea than as a reality, given how embedded these dominant narratives are for many people. How do you support Pacific stories to be more than an aside to these grand narratives? Is it a question of re-centring?

SM: It is a simple idea, and just one approach we use that shares the authorship and opportunity to write with other people. For example, the multi-authored book Tangata o le Moana involved 14 emerging and established writers, among them anthropologist Melani Anae, a founding member of the Polynesian Panthers, who wrote a chapter covering the Dawn Raids and the activism of the Panthers; and sociologist Cluny MacPherson, a deacon in the Pacific Islanders’ Congregational Church, who wrote the about the influence of the church in its formative decades. They brought their writing and analytical skills to the task of storytelling, but also their firsthand experiences as participants in the events they describe. It would be difficult to look past them as contributors, although they are not the only people who could have written those chapters. We wanted their perspectives as people who lived through those times, but also as people who could look back and reflect on the legacy of what happened. Similarly, ten years earlier, Fulimalo Pereira and I co-edited Pacific Art Niu Sila: The Pacific Dimension of Contemporary New Zealand Arts (2002), which involved 16 writers – some of them writing for the first time, some of them artists/practitioners or emerging academics. In Tatau, we have 16 writers, ten of them Indigenous, eight of them women. They include art historians, poets, theologians, language experts, photographers and tattooists. Sure, these contributions can be seen as asides to the central narrative, but I’d argue their presence actually helps constitute and complicate the narrative, supporting the idea that there are multiple ways to think about, experience and write about tatau. I’d hope that the books I mention here have expanded the group of people who are writing our histories, developed their skills and created space for others to have a say. Big book projects have that potential, to carry with them more than what is written on the page.

LL: On the topic of books, Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing is beautiful and the titles you’ve mentioned already are not only great texts but the books themselves draw readers in. I'd be interested to know how you think through the presentation (or maybe distribution) of history, is the aesthetic component important? Do you think about presenting your histories in accessible ways?

SM: As someone working in a museum with material culture, I am invested in drawing readers’ attention to the things our ancestors and contemporaries have made, and thinking of ways to make the stories about them accessible to people. I’m always looking for opportunities to use material culture to illustrate my writing, or rather using material culture to inspire my writing. Sometimes we get opportunities to make exhibitions and books, or just one or the other. In some ways, a book is like an exhibition, where you assemble all the stories and objects, and work with various experts, artists, designers, editors and publishers to create a product people can engage with. However, unlike a large museum-scale exhibition, a large book is usually cheaper to produce, you are less limited by word count, more people will engage with it and it will be around a lot longer for people to read, think over, critique and hopefully build upon.

As for creating beautiful books, I am of course indebted to publishers and designers with a vision, and a collaborative mode of working. However, in the past I have found it difficult negotiating with designers about what I would like to see and what booksellers need to market and sell a ‘Pacific’ book on cluttered bookshop shelves. There can be a tendency to overdesign, or overuse Pacific-inspired motifs and colour palettes, when in my view the objects and artworks are the colours that a book or exhibition needs. Fortunately, with Tatau, Nicola Legat, the Te Papa Press publisher, had a clear vision for the book (more ambitious than what I had imagined) and she worked with designer Arch MacDonnell to produce this stunning-looking hardback that works with, but resists, a ‘Pacific’ design palette. The final look is pretty close to the original concept they proposed, not much has changed, although I did ask at one point that “we resist the ooga booga factor” just to keep us all in a pared-back design headspace, especially when we had such amazing illustrations and photographs to work with. I am more than happy with what they have produced – it does a certain job for marketing by utilising some bold typefaces and imagery we understand as Pacific, but without going over the top.

LL: I think about the anxieties I feel sometimes as a ‘Pacific critic’ – do you feel the pressure as a Pacific curator?

SM: I think within any academic discipline there is pressure; pressure to be accurate, to be scholarly, to be comprehensive and reflexive, and when you are writing about communities and cultures you are a part of, I guess there can be pressure not to upset anyone or challenge well-established or popular ideas. I am often anxious about what I am writing, however, I also feel excited about the prospect of sharing a story, or a new insight. Pulling this stuff together is not straightforward and it is often political. Whatever I put out there, I have to stand behind, and no matter what the approach, there is always a set of dilemmas to consider, and more often than not a critique to respond to.

The exhibitions, books and programing we create in museums are not neutral, they are political in the sense that they reflect our ideas, our personal biases and subjectivities

The exhibitions, books and programing we create in museums are not neutral, they are political in the sense that they reflect our ideas, our personal biases and subjectivities. In fact, if I raise my head up and look over the top of my computer screen I see a black t-shirt hanging on the back of a colleague’s chair that says “Museums are not neutral.” It is in my line of sight every day. I don’t think we can be balanced in what we create or the messages we share, we can and should take a position on issues.

LL: Collections are often thought of as being fixated on the past, but perhaps collecting and archiving are more accurately present-day practices which preserve contemporary objects and measina for the future. How do you ensure your collecting is future proof?

SM: Contemporary collecting has been a key thread of our work for the past 20 years. In the past three years, we have devised a series of targeted co-collecting projects. In 2016, Nina Tonga (Curator Pacific Art) and I collaborated with Humanities Guåhan on a co-collecting project representing the arts of Guam’s Indigenous Chamorro people. Together we assembled a collection that included works by master carvers, weavers, jewellery makers and blacksmiths. In 2017, Nina led us in co-developing a fieldworker programme among Tongan communities in Auckland, with the aim of developing contemporary cultural collections for the museum. This included a group of Tongan teenagers from Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate representing the experiences of Tongan youth, and fieldworkers covering the areas of Tongan fashion and Tongan kava clubs. Also in 2017, in a project developed by Rachel Yates (Curator Pacific Cultures) we worked with Tokelau-based fieldworkers to collect artefacts, interviews and photography related to the theme of living with climate change. A key element in all these projects is that the communities selected what objects should represent them in the museum. It has been a challenging but rewarding process, highlighting the benefits of sharing with our people the opportunities to think about and materialise history in museums.

LL: And what work is still to be done, what gaps are you moving on filling next or currently?

SM: In the next couple of years, we will be moving to develop new exhibitions at Te Papa as part of a renewal of the spaces currently dedicated to Māori, New Zealand History and Pacific Cultures exhibitions. This process will be the catalyst for new research and projects where we will continue reframing and exploring how we represent Pacific people’s histories in the national museum. On another level, I have some shorter pieces of writing in press as part of other people’s books on museology. I am keen to write about the collections here at Te Papa and maybe co-author a longer article or two about particular objects. I also want to research and write some more on tattooing as time allows.