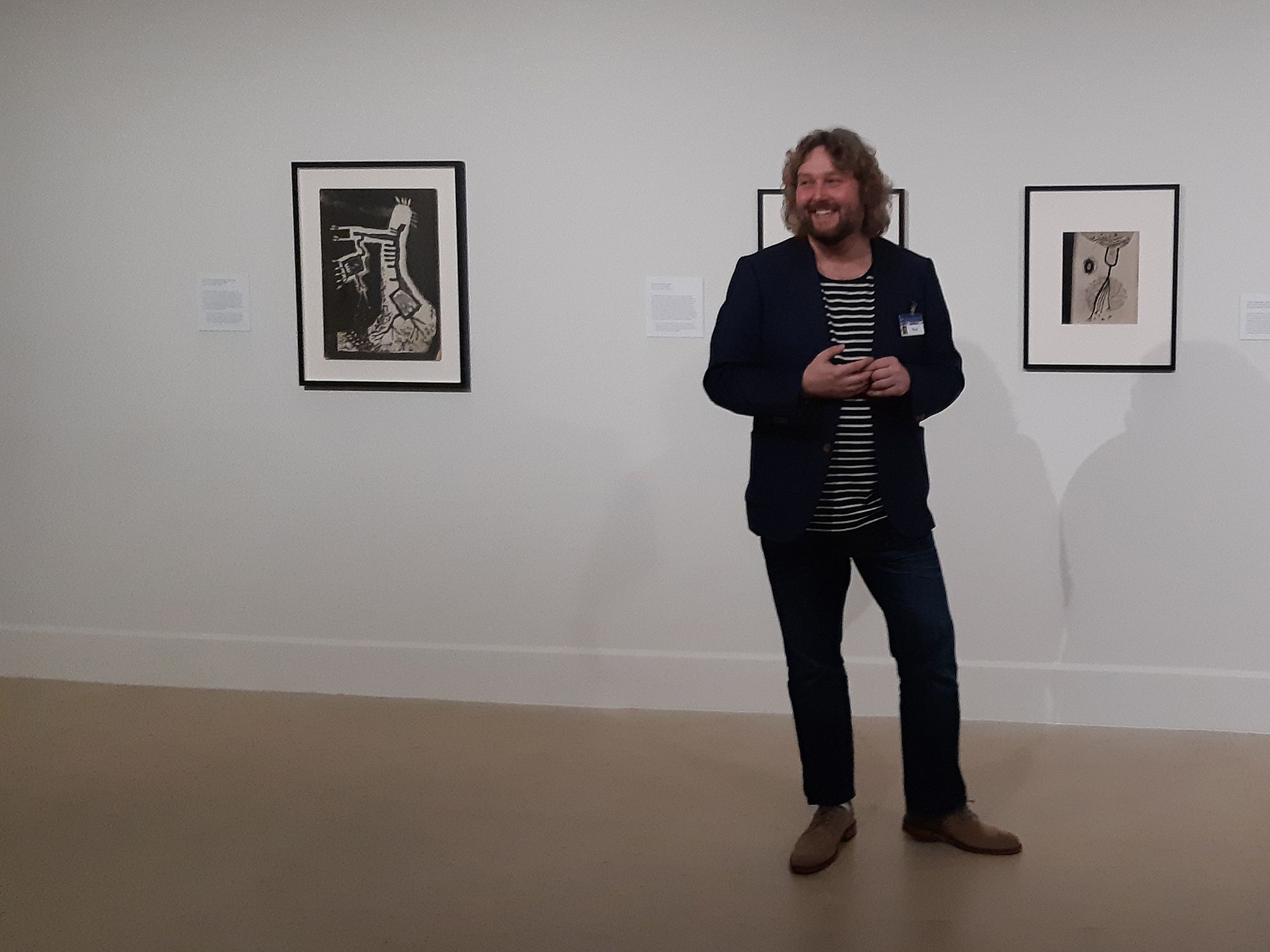

Cyclical Rearrangements: An Interview with Paul Brobbel

Alice Tappenden talks to Len Lye Curator Paul Brobbel about his singular role

Alice Tappenden talks to Len Lye Curator Paul Brobbel about his singular role.

Since the iconic mirrored walls of the Len Lye Centre at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery went up in 2015, the Taranaki gallery has had its fair share of highs and lows. Despite political controversies, aggrieved locals, and recently introduced door charges, the gallery team has continued to curate a stream of interesting and challenging exhibitions. Paul Brobbel started working at the Govett-Brewster in 2007, becoming Len Lye Curator in 2010. As a constant figure amidst the sea of change, he occupies a curious space in the arts ecosystem of Aotearoa. How does he approach curating one artist’s body of work? What does he do to keep locals and out-of-town visitors engaged and interested? And what might the Len Lye Centre look like in a century’s time? Over email, Paul and I unpacked these questions and more.

*

Alice Tappenden: So, it probably makes sense to start at the beginning. You started your museum career as a collections manager at Te Papa, then moved to the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery (before it became the Govett-Brewster and the Len Lye Centre). What did you know about Len Lye before you started? How has your experience changed these perceptions, if at all?

Paul Brobbel: Prior to Te Papa, I had been at Auckland Museum and Puke Ariki in New Plymouth, and had spent more than six years working in various collection areas. Academically, I'd worked across a wide range of fields including computer science, ancient history, English and museology. Working with modern and contemporary art wasn't something I had anticipated.

I was aware of Len Lye prior to moving to New Plymouth in 2007 but only became familiar with his work through Tyler Cann's (Len Lye Curator 2005-2010) exhibitions at the Govett-Brewster. I was an intern working with the Len Lye Foundation collections through 2010 and ultimately succeeded Cann. I think the important thing to note is that Cann's appointment in 2005 marked a very important expansion in the care of the Len Lye Foundation collections. Much more of the collection was to become accessible with professional staffing. I had the fortune of more than a year working with Cann, spending 40-hour weeks working in the collection absorbing everything, from one end of the collection to the other. Since I didn't come from a film or sculpture background, I had an indiscriminate approach to what I wanted to learn of Lye's work.

Like most people, my basic understanding of Lye came from Roger Horrocks’ biography. What struck me about Lye when reading the biography was that he was incredibly well-liked and respected. I couldn't detect any substantial counterpoint to this image of Lye; however, this adds to the idea of Lye as the effervescent, happy-go-lucky character. I think my time in the archives here has given me another perspective of a serious, driven and uncompromising artist.

AT: As the Len Lye Curator, you’re in charge of both curating exhibitions and looking after a vast collection of art and archival material – jobs which in most mid-sized institutions are allocated to different people. How did your early experiences in the sector shape how you approach your role today? And how do you manage these competing demands day-to-day?

PB: The duality of this role is necessary given that much of the collection and archive remains uncatalogued and a great deal of research is still to be undertaken. Nearly all of Lye's work is here, so in order to be an expert (or even familiar) you need to know the collection and that means, at present, being intimately involved in the appraisal and registration of it. An important thing to stress, and a key aspect to the idea of a Len Lye Centre, is the work that goes unseen – whether that's the digitisation of the audio archives, conservation of Lye's paintings, or a myriad of other projects now underway.

I'm not aware of having a particular approach to this, or that these aspects of the role are competing. Exhibition making is often driven by the activity around the collection, where new ideas or urgencies develop. Likewise, new activity in the collection is resourced by exhibition ambitions.

I think there's a growing separation between curators and collections, to the point where you can curate alongside an institutional collection now and the interaction is only periodic or ad hoc. There's a de-skilling of curators willingly underway, so I'm fortunate that neither making exhibitions nor collection care dominates my role, they are equally weighted.

You learn pretty quickly that it's been done before and it'll be done again, but I'm clear in my mind that there is always a new audience in front of you

AT: The curatorial aspect of your work is also an anomaly in Aotearoa. You have the challenge of curating the same artist’s work over and over again, while keeping the exhibitions fresh. In order to do so it’s likely you have to balance your in-depth knowledge of one artist’s work with a variety of wider perspectives, and the work of other artists. How do you keep things interesting? Do you look to overseas institutions for approaches, or inspiration, to address these challenges?

PB: There's certainly a cyclical sense to making exhibitions around Len Lye. You know the same ideas will come around again and again. You learn pretty quickly that it's been done before and it'll be done again, but I'm clear in my mind that there is always a new audience in front of you. Similarly, there are decades of exhibitions behind us that are poorly documented and not always accurately remembered, so I don't feel restricted by the past. I'm more mindful of the future. I believe that as we make exhibitions now, they will become reference points for future exhibitions. I'm comfortable in leaving things to be continued. This interplay between exhibitions has somewhat happened with the Points of Contact: Jim Allen, Len Lye, Hélio Oiticica (2011) exhibition referencing Action Replay: Post-Object Art (1998). I think the opportunity of the Len Lye Centre will ensure that exhibitions speak from one to another.

In terms of artists beyond Len Lye, including contemporary, this is essential and I've always felt that Lye is at his best when not seen in isolation. There's a sense in which casting Lye as a 'maverick' does well for promotion but it's not my approach. It's challenging in a city the size of New Plymouth to attest to the value of Lye as a filmmaker and generate an audience for a Hans Richter film screening. One of the recent highlights of my time here has been bringing artists like Steve Cossman and Jodie Mack into the programme and exploring cinema through their work, both running workshops and pressing the point (for me, and I hope to the audiences) that the thrill in what Lye did with cinema hasn't dissipated with time into a mere museum ‘Instagram’ moment but is still happening close to 100 years later.

These are among the most rewarding projects to develop because there is an element of the unknown in them and a sense that we get to do them because of Lye – that Lye opens up opportunities few other museums can undertake

Our 2017 exhibition On an Island: Len Lye, Robert Graves and Laura Riding serves your question well. Beyond the crowd-pleasing expectations around kinetic sculpture, we get to work with the very rich and rewarding question of Lye and Modernism. It's a fringe interest (or discovery) for most of our audience but essential in exploring who Lye was and what he did as an artist, in my mind absolutely essential in an artist's 'centre.' On an Island considered Lye's relationship with the poet/critic partnership of Graves and Riding. Each was a significant influence on Lye early in his career and both are challenging identities around which to build an exhibition. The point of the exhibition, as much as to illuminate Lye's development as an artist, was to bring Riding into view – one of the most important figures in the Len Lye story and herself long overdue an audience. The exhibition itself could only serve as a limited introduction to Riding; however, in establishing literature as a key part of Lye's oeuvre, it did so hand in hand with the writing of Riding. Keeping the exhibition focused on that achievement, we produced a small symposium (hosted at the University of Auckland) to extend the project to a point where Riding could be the greater focus of our attention.

Exhibitions like On an Island are an essential part of the programme alongside the exhibitions that are tightly focused on Lye's work. These are among the most rewarding projects to develop because there is an element of the unknown in them and a sense that we get to do them because of Lye – that Lye opens up opportunities few other museums can undertake.

I'm not sure I find too many international lines of inspiration as there are few models for this kind of institution and where there are, the resources available are incomparable. There are particular museums I keep a close eye on – the Nam June Paik Art Center, The Henry Moore Institute, Museum Tinguely, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image and Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive.

AT: How does it feel to be working with an international artist in the context of a regional gallery? I understand you get the lucky job of travelling internationally, given Lye’s work is so grounded in a global context. Do you feel any pressure to make the work appealing and accessible to a wide range of visitors (local, national and international)? Do you have certain strategies for ensuring the work you do reaches these different audiences

PB: Exhibitions tend to be developed along the lines of either introducing/surveying Lye's work or exploring some part of it in detail. These two things happen side by side through concurrent exhibitions and, ideally to some extent, within each exhibition. I'm mindful that local or repeat audiences appreciate something 'new,' so there's nearly always something unfamiliar within each exhibition. But we get a great deal of feedback about the perceived primacy of Lye's kinetic sculpture and why this isn't always and comprehensively leading the programme. It's a simple museological imperative that these artworks are not overworked and displayed too frequently. This rules out long-term exhibitions and makes it incredibly challenging to produce five to six Lye-focused exhibitions per year that are contextual, cohesive and ethical.

One of the difficulties here is that Lye's international reputation and the local perspective are not in agreement. Lye's acclaim internationally is centred on his achievements as a filmmaker. His kinetic sculpture is a secondary consideration, if it's known at all. This is a characteristic of kinetic art and how poorly it has fared internationally in museum collections. While Lye's sculpture has been kept at some distance from the rest of the world, it has rendered the Len Lye Centre one of the most unique collections of kinetic art. Also one of the most challenging to operate, so we are constantly improving the programme to balance audience needs.

I've often said Lye gets us a foot in almost any door we want, and other deserving things get through the other way

AT: The Len Lye Centre, dedicated to the work of one artist, is the first of its kind in Aotearoa (well, according to the Foundation’s website). It’s also possibly the last (one could argue that the Hundertwasser Art Centre, another regional gallery-slash-tourist-attraction, will serve a similar function, but that remains to be seen). What makes Lye so deserving of this honour, and can you see any other New Zealand artist ever achieving a similar feat?

PB: Foremost are the circumstances around his work being bequeathed to the people of New Zealand and being stored in one location. The films are necessarily the domain of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision because of their technical expertise, but most of the work is here in New Plymouth. There is just a handful of Lye's works anywhere else in the world. So given the Govett-Brewster is the home of Len Lye by default, with or without the bricks and mortar of the Len Lye Centre, then the question is whether Lye deserves the forum of a museum of his own.

One interesting aspect of our work here is that in the area of unrealised sculpture the works are yet to be built, the majority of the collection there is cataloguing to be completed, and extensive research yet to be undertaken. So the world of Lye is only going to get bigger. As the picture of Lye gets bigger, the world that he occupies expands and, for me, that's what the Len Lye Centre provides – an entry point to Modernism, experimental cinema, Surrealism, kinetic art, animation. These are all elements of the Lye story but they are portions of a larger story as well and we get to work with all of these rich areas. I've often said Lye gets us a foot in almost any door we want, and other deserving things get through the other way. I don't see any other New Zealand artist achieving a similar feat, Lye just takes us to so many places.

AT: It’s interesting to me that, according to this Wikipedia entry, the vast majority of single-artist museums are devoted to the work of white males. When curating, how conscious are you of issues relating to diversity and gender? Do you attempt to create exhibitions that reflect a broad range of views and experiences, and if so, how do you accomplish this given there’ll always be at least one Pākehā male heavily featured?

PB: It's a particular challenge given we're starting with a male artist and therein working with fields like experimental cinema and kinetic sculpture that have their own attendant imbalances and blind spots. One of my responsibilities as Len Lye Curator was overseeing the establishment of the cinema programme at the Len Lye Centre. There's a canon in experimental cinema that is going to be all male, if you let it. I can note that other than Lye, the artists surveyed with solo programmes in the LLC cinema have all been women (Shirley Clarke, Merata Mita and Jodie Mack) but those are curatorial decisions and we need to be sure we also work with a wider programming ambition.

It was an important decision early on that we would make contemporary film the principal focus of the cinema programme rather than modern cinema centred on Lye. It's a simple belief that what's good for contemporary filmmaking is good for Lye as a hero of cinema. So the Len Lye Centre cinema has been principally created as an environment for film festivals, workshops, Q&As with domestic filmmakers, all of which we continue to expand each year. I'm hoping that this denies the inherent myopia that comes with a single artist programme and allows for something much more inclusive and accessible.

I don't think that outcome could have been anticipated but it makes clear how quickly a familiar work can be presented with a new and definite impact

To similar ends, the curating of cinema here is driven by a programme called the Projection Series and our biennial CNZ International Film Curator in Residence. Each of these programmes was developed to open the curation of cinema in the Len Lye Centre to outside contributions – whether that's alternative voices working with Lye or bringing in projects outside our in-house expertise.

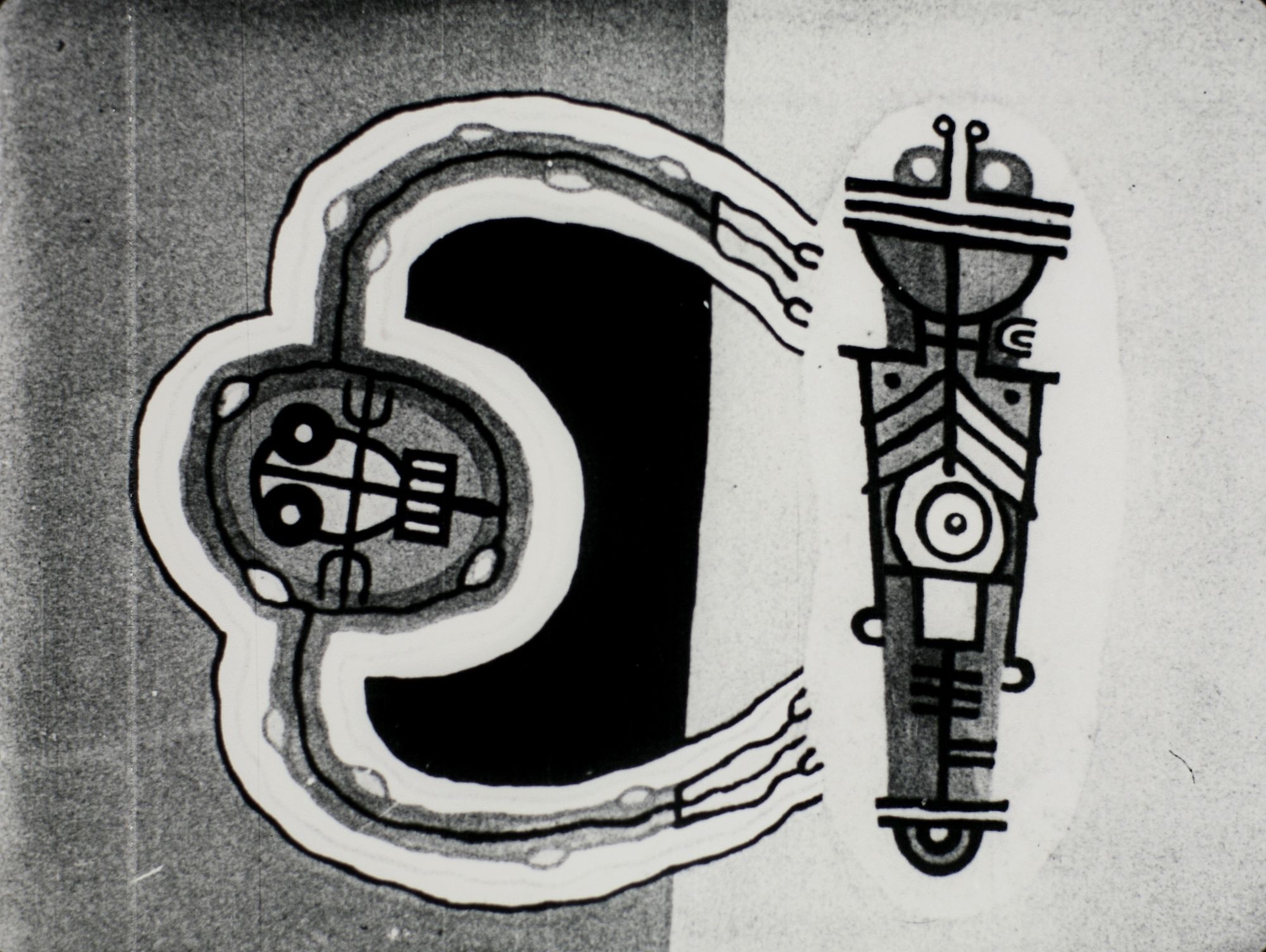

There's likewise a steady approach to finding different perspectives and voices in making exhibitions, whether that's collaborating more frequently with guest curators or using Lye's work in concert with contemporary activities. Our present suite of exhibitions includes Sensory Agents (curated by Sarah Wall) which takes the aural qualities of Lye's work as a point from which to consider contemporary artists working with sound. Lye is heavily represented in the exhibition but accompanied by more than a dozen contemporary artists, all with new work. In 2013 we collaborated with Mangere Art Centre – Ngā Tohu o Uenuku on the Agiagia exhibition, which included a public programme presenting new soundtracks for Lye's Tusalava film by three contemporary composers. Five years on, these compositions accompany Lye's film in Te Papa's Kaleidoscope: Abstract Aotearoa exhibition. I don't think that outcome could have been anticipated but it makes clear how quickly a familiar work can be presented with a new and definite impact.

AT: There’s also this interesting aspect to your role as posthumous producer. Together with the Len Lye Foundation and the all-important engineers who have to make the works ‘work,’ you get to decide what the next Lye will be. How do you feel about your role in this history? And where do you see the centre in, say, 100 years time?

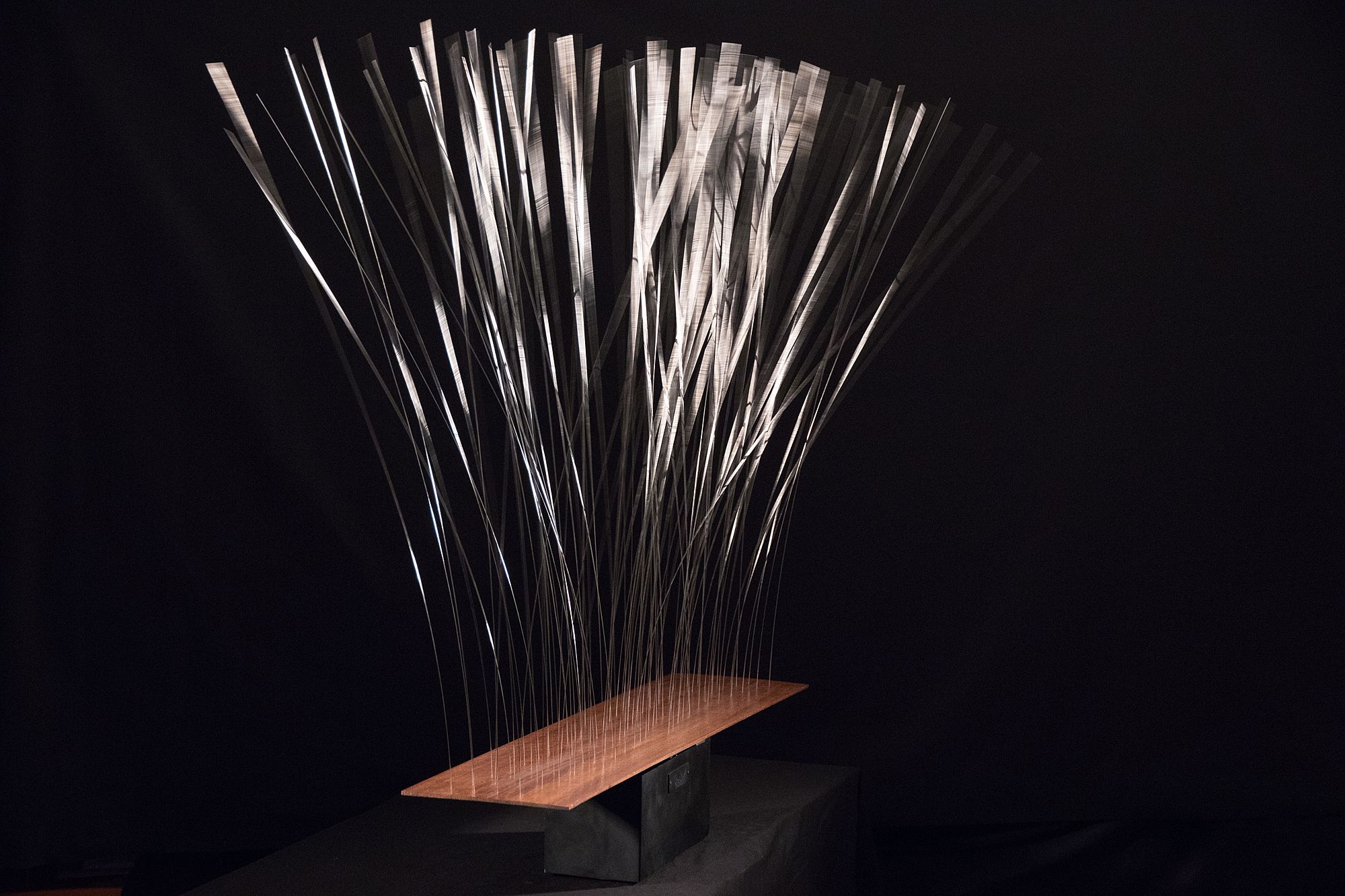

PB: This isn't my role to any great extent. I have a professional perspective on what would be interesting to see realised if it's presently not in exhibitable state. But you can consider that as a list of projects in various stages of progress with the Len Lye Foundation and I might bump something along a little if there's an exhibition in mind. This December you'll be able to see a new large-scale work developed by the Foundation called Dancing Wands, and another exhibition will include a reconstructed work called Watusi.

My role is more significant in the area of conservation, whether that's kinetic sculpture, painting or audio recordings from the archives. I work closely with museums overseas with Lye works in their collections and negotiate the restoration of those works through the Len Lye Foundation. We've recently returned works to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (Buffalo). Since most of Lye's work resides in New Plymouth, an active body of works in the northern hemisphere is paramount to increasing the international visibility of his sculpture.

One hundred years from now the 'museum' will have been through such change that I don't see it existing as we presently understand it, if at all.

AT: Finally, something lighter. What’s the most surprising thing you’ve discovered about Len Lye? What would you currently say is your favourite work?

PB: Most who know Lye are familiar with the unrealised projects, but there's a much greater world of the incomplete or unrealised Lye than is widely known. Horrocks’ biography notes that Lye was teeing himself up to direct the film adaptation of George Orwell's Animal Farm (the letter from Orwell in the archive is one of my favourite items). Likewise, most are familiar with Lye's brief involvement with Alfred Hitchcock but few would know Lye worked briefly on special effects storyboards for the 1961 3D horror movie, The Mask. As ever, Lye's work didn't make it to the screen. Recently, I read a letter in the archive outlining Lye's role as a producer for an epic post-World War II Iranian film. It all makes me wonder which of these could have been a turning point, denying the Lye we have with us today.

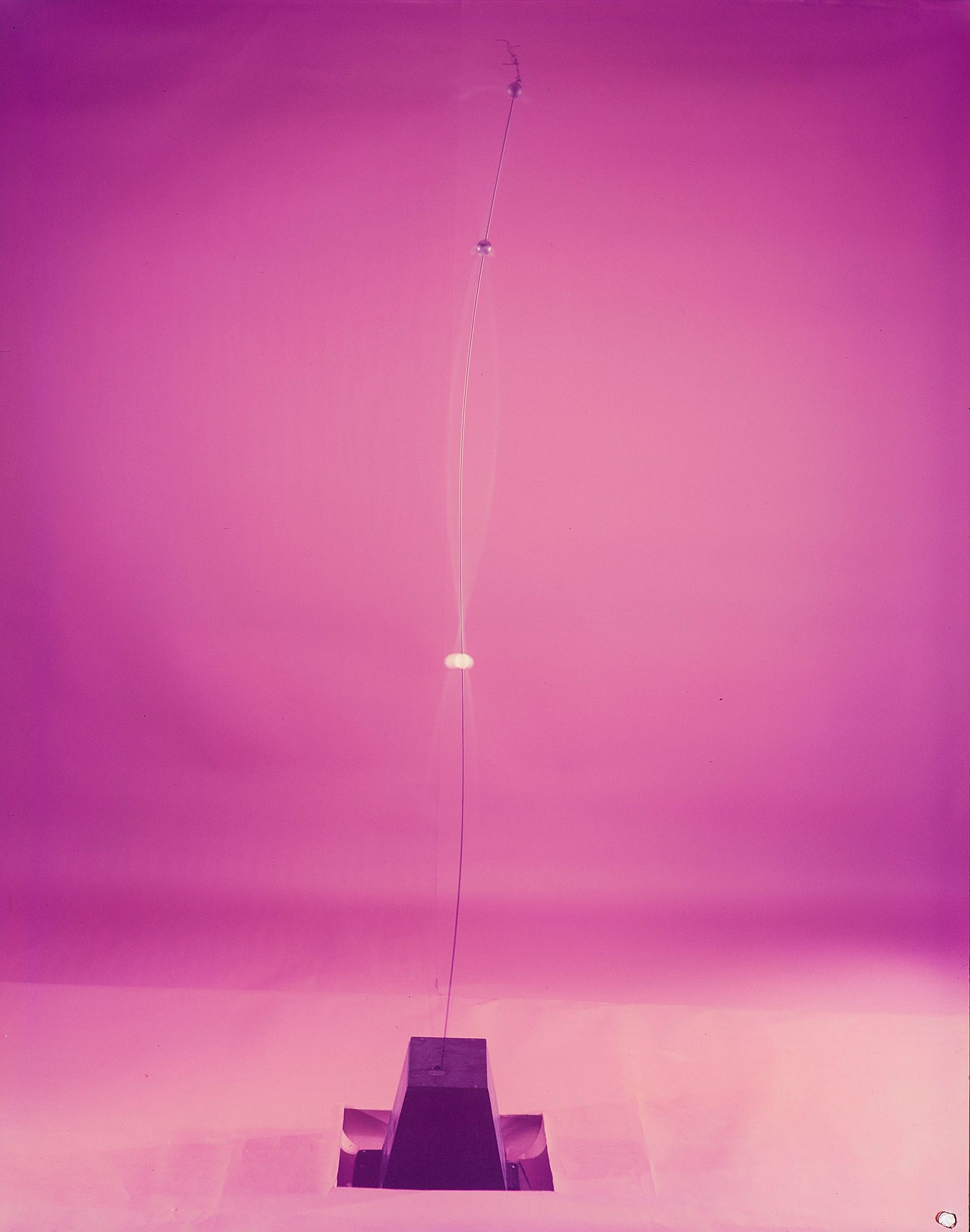

Presently, my favourite work is Grass. It's quite well known and at the gentler end of Lye's sculptural oeuvre in terms of energy and sound. The collection here holds the version known to many and one of my fondest memories of the work is having a live jazz band play “My Funny Valentine” while Grass performed. This was one of several pieces of music that Lye said would work well as accompaniment. Right now Grass is fresh in my mind because we recently completed a project to conserve a smaller version of the work in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. Seeing the work in one of my favourite museums but not performing was bittersweet. Being able to bring it to New Zealand for conservation is one of the most rewarding things I've achieved here.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.