We Strive To Please: An Interview with Pop-up Globe's Miles Gregory

As the Pop-up Globe's second season starts to wind down, Kate Prior sits down with Artistic Director Miles Gregory to get beyond the bluster.

As the Pop-up Globe's second season starts to wind down, Kate Prior sits down with Artistic Director Miles Gregory to get beyond the bluster.

Dr Miles Gregory smokes rollies. I don’t know why this surprises me. Perhaps because I always connect the image of pouch tobacco to my carpet layer Dad, not Shakespeare scholars. He meets me, rollie in hand, in a carpark at Ellerslie Racecourse. We pass the box office, round the corner, and are met by the three storeys of his white, corrugated iron Pop-up Globe.

Born in Wellington, Miles grew up in Auckland and left the country for the UK shortly after finishing high school. He spent 20 years there and in that time completed his doctorate in Shakespeare in Performance at Bristol University, became a regional producer for Shakespeare’s Globe, a producer of the British Touring Shakespeare Company and most recently the Chief Executive/Artistic Director of The Maltings Theatre in Berwick-upon-Tweed, before moving back to New Zealand.

In 2016, Miles embarked upon his most ambitious project to date. With his business partner and old mate from King’s College, Tobias Grant, he created and ran a full-scale temporary working replica of Shakespeare’s second Globe theatre in Auckland’s Lower Greys Ave car park. In the lead-up to the first season, he described it to Jesse Mulligan on Radio New Zealand as “without doubt, the most exciting project I’ve ever worked on in my life”.

Moving the theatre to Ellerslie racecourse for a second season in summer 2017, Miles and Tobias’ Pop-up Globe has sold over 150,000 tickets over the two seasons combined. Since the first iteration, there have been improvements to the structure and a second resident company added, meaning more shows and longer seasons. Now, the two resident companies are about to head into their final three weeks performing in the scaffold and corrugated iron ‘O’ before it all gets pulled down again.

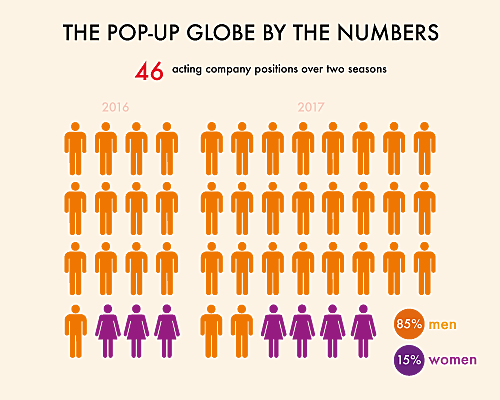

As we grab a coffee from the container bars next to the theatre, Miles gets the latest news from a stage manager passing by. It’s been a particularly full-on week for the theatre, for various reasons. “I’ve taken up smoking again” he says. He has a clipped, brittle tone. This is probably because he’s tired, but also because he’s somewhat on guard. Amongst the immense popular success of the Pop-up Globe, there’s been industry frustration. The amount of international actors and directors employed are amongst issues that have been raised (almost a third of this year's company are international – mostly graduates from London's Central School of Speech and Drama where one of the directors also works). The leadership team has also copped a fair amount of criticism from academics and industry alike for doing the all-male cast thing for the second time running (meaning out of 46 acting company positions over two seasons, 7 have been held by women). My motives for an interview are viewed with a polite suspicion.

I’ve been curious to have a conversation with Miles for a while now. His project is a unique and exciting proposition to the Auckland theatre ecology. But outside of the numbers bluster and front-page Herald ads on one hand and frustrated opinion pieces on the other, I’m interested in what the project means for him. And what exactly is historical accuracy?

We take a seat in a room that was once a rehearsal space; yellow electrical tape marks out the stage on the carpet, tables and chairs are pushed to the edges. It’s clear Miles has talked to many funders with many sauvignon blancs on many opening nights. Positions on Shakespeare come easy – when he's in that sweet comfort zone, the sharpness is exchanged for a cool, measured pace. This is undercut by an insistence of vaping, which has replaced the smoking, and intermittently he’ll be clouded in a plume of vapour before making his next point, like a true Shakespearean spectre, wearing a baker boy hat.

As Miriama Mcdowell’s Much Ado About Nothing begins in the theatre nearby, we get on with our own Much Ado, the room slowly filling with vapour, ready to talk about a guy who wrote some plays for his mates 400 years ago.

Kate Prior: The fact that you’re now nearing the end of the second season of this incredibly financially successful project, I’m interested in the things you learnt from the first season which you took into this one?

Miles Gregory: Well the first season was a sort of cataclysmic event in most people’s lives who worked on it. It started as a dream and then very quickly became very concrete. That process was very rapid – we went from a team of two and half people to a team of about forty or fifty people in six weeks.

So by the time we actually opened the first season I think we were all absolutely exhausted. It was a very joyful time, but also a very tiring one.

KP: Was that surprising?

MG: Well, we knew that people would buy tickets to see a building like this, so that wasn’t totally surprising. We also hoped that we would make work that responded and respected the building, and that connected with our audience because that’s something that I’m very passionate about. And we did that. I think what was surprising was how many people came to see it. And how transformed many of our audiences were by what they saw.

Of course in our first season there were nine or so productions. Only two of those were made by us, but they formed the backbone of the season. But certainly both of those shows achieved critical acclaim and were immensely loved by audiences in ways that I hadn’t seen audiences love work before. So that was surprising perhaps; the depth of feeling was surprising.

KP: So not only the sheer numbers but the quality of the response?

MG: Yes, and the multiple attendances, particularly by young people.

Also what was quite surprising was how divisive the project was in the arts community.

KP: Right.

MG: Which was something I’d not experienced before. So that was truly surprising.

KP: So that wasn’t something that you’d expected?

MG: My understanding of theatre – having worked in it since I was very young, making Fringe theatre for five years, and then bigger theatre as well – is that the arts community is a very supportive one. Critics may take exception to shows. Individual audiences might. But generally theatre is such a tough industry to work in, and people pour so much of their lives into the work, that I would have expected more support from that community.

I understand some of the reasons why there wasn’t. I’m not blind to the reasons.

KP: What do you think some of the reasons were for that response?

MG: Well, there were some articles published that suggested we should have consulted more with the arts community. But in making theatre, I’ve never consulted with a community about it. Why would you? Who would you consult with?

KP: I think in terms of coming into a precinct – for instance, in that first season you were in the Lower Greys Ave carpark in front of the Basement Theatre and behind Q Theatre and I guess you’re quite a commercial entity at the base of it…

MG: Are we?

KP: Well, that’s also a question I have.

So coming directly into an arts precinct, and being in direct competition…

MG: Competition?

KP: In direct competition with the Auckland Arts Festival for instance…

MG: I don’t think of theatre, or of arts as being competitive, that’s not a word I would use.

KP: Okay.

MG: Simultaneous perhaps.

KP: Okay. So that’s your answer to the question that was raised of direct competition?

MG: That it was built in the arts precinct and happened simultaneous to other arts events? Of course, all art happens simultaneous to other arts events. And if you were thinking about a place to make theatre, the natural place to think about doing it would be in a theatre precinct.

There was a huge amount of consultation with the Basement Theatre and with Q Theatre and with Auckland Live, who were indeed extremely supportive. We consulted with our neighbours. We couldn’t have done it without their support.

MG: I would say that the argument generally in the arts is that when more theatre happens, more people attend theatre. And when more theatre happens near one theatre, more audiences attend that theatre. So I see arts as being mutually beneficial for different arts organisations. And if it’s a different genre, then there’s no competition.

To be honest with you, I generally don’t understand. We didn’t make this project to upset people. People are upset – that illustrates a depth of feeling. I’m glad people have a depth of feeling about this project.

KP: I'm not sure about 'upset', but in any case I think there’s huge potential for those feelings to shift and change. I think there’s always that shock of the new which is a natural human instinct. It happens when people don’t necessarily have underlying connections or relationships over time. So a new entity is sometimes affronting, perhaps.

I think the artist has to make work for where they are – that's their job.

MG: Yes. I mean, it’s very difficult changing countries and making work. I don’t have a network in New Zealand. I don’t really know anyone in New Zealand.

KP: Why did you want to do this project in New Zealand?

MG: Because I’ve spent 18 years working outside of New Zealand, and I’ve always wanted to come back and make work here – to bring back everything I’ve learned overseas.

This project works in a field that I’m trained in and I enjoy, so it seemed to be a natural project to do here. Also I now live here, so it would be odd to go and make work somewhere else. I think the artist has to make work for where they are – that’s their job. Whatever community you live in, it’s your job to make work in that community.

KP: So if there’s that keenness to make it a New Zealand project, in New Zealand, why cast from overseas?

MG: One of the amazing things about theatre is that when it’s made by people from many different nationalities, ethnicities, genders and backgrounds it becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Ever since I encountered the work of Peter Brook when I was very young, I believed in internationalism in theatre.

I think particularly in New Zealand, or in communities that are not at the heart of Europe or America – more isolated areas – when you bring together national and international actors, an amazing thing happens where they inspire each other. They make better work because they’re on show to each other. There’s an incredible blend of cultures that comes together, that makes the work greater than something that’s a local celebration. I actually think it shifts the focus off nationality and onto the work. So it makes the work the star.

It wasn’t even a decision, it’s just a way of working that celebrates the work.

KP: And were you looking at international influence in those leadership roles, such as the directors on each production as well?

MG: Well, theatre is a collaborative industry, and when you work on a project that’s in itself an immense challenge, it’s very important, and very natural, to want to work with people you’ve worked with before at the top of it, so that you can relax and know that the work will be made. It takes a long time to identify collaborators – it can take many years of working with people before you’re sure that you trust them with the work.

As I’ve said, not working in New Zealand before, I don’t know any New Zealand directors. It’s one thing to hold open auditions and to find actors to work with – that’s how actors work, but it’s a highly risky project that I had staked my own house on, so inevitably I was looking for people to work with at a senior level who I’d worked with before.

It takes a long time to identify collaborators – it can take many years of working with people before you're sure that you trust them with the work.

So this year I’ve worked again with the UK director Ben Naylor, who’s shown himself able to direct very finely in the space, and another long-term collaborator, a director from the UK called Tom Mallaburn, who I’ve worked with for 20 years.

I struggle to get out and see new work. Partly because I have a young family, partly because of the demands of my job and where I live. So it’s quite hard to identify new directors to work with.

KP: How long do the director and actors get in the actual theatre space? Because it’s such a specific space to perform in – are they rehearsing in that space?

MG: No, it’s built as they rehearse, so I think we had about four days in the space before opening night, for four shows, and a lot of rehearsals took place while the building was being constructed around it, in almost impossible conditions.

KP: So you’re needing directors who are aware of working in those conditions.

MG: Yes – directors who will trust me as a collaborator, and cut me some slack as we bring the project together. And that’s about trust isn’t it.

KP: That essential thing.

MG: Of course, we’re a very young company – we’ve only made two projects. I think when we’ve been around longer we’ll have the opportunity to work with many different people, and to make many different types of work. But since we’ve started we’ve worked frenetically to bring each season to pass, and there’s not been time really for reflection.

So we’re working at the moment under an artistic vision that will see us through for one more season, and I hope by then we’ll have time to consider the next three years.

KP: So next summer we’ll see a third season of the Pop-up Globe?

MG: It’s too early to say. We have to take stock of what’s happened this year – how it’s been received. We have sold a lot of tickets again. So there seems to be a lot of demand for more Pop-up Globe. And I suppose as theatre makers we’ll keep making work while there’s demand for it.

KP: It really struck me at Much Ado About Nothing the other night, the diversity of the audience – especially the groundlings – in age as well as ethnicity, but especially age. Such a young crowd – it’s really exciting.

MG: Yes it’s an amazing thing – the performances attract such a diverse audience, especially such a young audience. A third of our tickets are $15 or under. Of that third, many of them are actually $1, so to be able to take your family of five to a piece of theatre for $5, to me is a reflection of the values I have about the accessibility of theatre. I think theatre is generally too expensive. People can’t afford to go. I mean, I can’t afford to go to theatre in Auckland.

One of the great things about theatre is that, compared to film for instance, it’s very cheap to make. Ticket prices should reflect that, even if it’s a limited number of tickets for a very small amount of money. It’s about reducing the risk for the audience. Audiences always take a risk when they come and see work, and if the ticket price is quite high, that makes the risk very large, particularly for new writing and newly established companies. So I think theatre makers have an obligation when they make the work to consider how they can reduce the risk for audiences to attend. And one strategy needs to be around ticket prices.

KP: And that’s also offset for you by the more expensive seated tickets in the space.

MG: Absolutely – you can pay a huge amount of money. If you want to, you’re welcome to, and we’ll give you a very good experience doing that. But conversely you can see it for $1.

I think Shakespeare is death to the box office.

KP: Do you think the major pull for audiences is Shakespeare or the building?

MG: I think Shakespeare is death to the box office. Shakespeare is very hard to sell tickets for – even established companies struggle to sell more than 10,000 tickets for a major season starring major people. The building is interesting and I think in the first season people came to see the building. And if it was the case that people came to see the building and the theatre we made wasn’t any good, people would stop coming – there wouldn’t be a second season. But it’s a combination of the way we make the work in the space. Our work is only made for that space. So I think people come perhaps to see the building but they stay because they love the theatre we make.

KP: And this season, audiences and critics have noted that the shows are stronger artistically – even better than the first.

MG: Good. I think they are.

I think last season confirmed a lot of beliefs that I have around the interaction between actor and audience. And I think this year we were able to make work that was higher quality, that responded better to the space, and that’s a good thing. And we were able to employ people on longer contracts as well.

KP: Because of the previous season.

MG: Yes, so we were able to pay actors better. We improved our pay rates and we rehearsed for longer.

For most companies, making a single Shakespeare play with integrity is a massive project. It’s very challenging. Your work is speaking to a performance history that spans centuries – there are high expectations. To make four plays with two companies is very difficult. The scheduling is difficult, the workload is high, and it’s very expensive. To then also build a theatre simultaneously is a very unusual thing to do as well. And a very brave thing to do. Possibly foolhardy. To then open those shows in that theatre as it’s completed is... I’ve seen that twice now and I’ve never seen anything like it. I mean, I know what production madness is and this is beyond anything I’ve ever seen.

To then also build a theatre simultaneously is a very unusual thing to do as well. And a very brave thing to do.

KP: You say foolhardy. So what was the driver? There’s always that thing that gets you through when you're at the “why the hell am I doing this?” stage. What was that fuel for you?

MG: The company. Everyone else.

KP: But before the company was on board, what was the spark, the reason that you thought, “I’ve gotta do this”?

MG: Well, I personally have seen the transformative power of Shakespeare performed responsively in a space like this.

KP: In Shakespeare’s Globe on the Thames?

MG: Yes, and in other similar spaces. So I know that it’s important. I’ve spent my life working with Shakespeare and his work is very powerful, it has a ritualistic power, it taps into deep human emotions. In that sense it’s quasi-religious. It has a strong connection with the Bible – Shakespeare’s work was written at the same time as the King James Bible. And his work – if we can understand it – offers us ways of evaluating our own lives that don’t come with other work perhaps.

MG: But one of the great blocks to Shakespeare is the way it has been taught in schools. And many people find Shakespeare difficult to understand and don’t really see the point of it. But I know that if his work is performed in a way that responds to that space and makes a direct connection with the audience then it becomes very comprehensible. And if you can walk out of a performance of an artist whose work you didn’t appreciate but who is held up as a great artist – if you can walk out of that performance for the first time understanding and taking joy in the work and saying to other people “Yeah, I love Shakespeare, I saw a great performance of it” and having the confidence to understand it, that confidence can spill over into every other area of your life. If you can understand Shakespeare, what can’t you do? The world is your oyster. He’s held up as being difficult, but we make it easy. And so I hope that influences people’s lives.

KP: And that is the reason you wanted to make a Globe space – to make Shakespeare live?

MG: To expose people who would never have the opportunity of going to another replica. To expose them to why his work is great, why his work is important, and how it can be life-changing today.

KP: Yeah, I went to Shakespeare’s Globe when I was 18 with Shakespeare Globe Centre New Zealand and saw Mark Rylance play Hamlet in the 2000 season. And I stood for three hours totally transfixed. It was the first time any of that had made sense to me.

MG: Well that's Mark isn't it.

KP: There’s also just that communal aspect of what a circle does. You know, you’re talking about ritual – there’s a lot of ritual and symbols in circles.

MG: And the building itself is heavily symbolic, so every element is representative, and even is representative of society, in the way that it’s layered. So that’s interesting.

But also I love a challenge and I’m a pretty determined sort of person, so there was no way we weren’t going to do it.

KP: Was it also seeing the success of stages like Shakespeare’s Globe?

MG: Well not really, Shakespeare’s Globe is a tourist attraction on the South Bank.

KP: I don’t know, I think it manages a pretty strong artistic output – the appointment of Emma Rice was really exciting and seeing her A Midsummer Night's Dream there last year I was kind of blown away by how artistically powerful and playful that was.

MG: Well it’s a massive, serious, vast undertaking. The Pop-up Globe is a bunch of scaffolding and corrugated iron. The work they make is very different too, they don’t make work like we make here. So no, not really. In fact we don’t have anything to do with Shakespeare’s Globe. They do good stuff, but it’s different.

I think it may have something to do with the Globe of 20 years ago, but certainly not the Shakespeare’s Globe today.

KP: You mean the first years of it – when Mark Rylance was Artistic Director?

MG: Yeah. I thought that was quite inspirational.

KP: Which is kind of a natural segue to the fact that those casts in the early days of Shakespeare’s Globe in the late 90s/early 2000s were doing the all-male cast thing.

MG: Some of them were.

KP: Yes, I remember seeing them.

MG: Not all of them.

KP: No.

But you know, interestingly one of the critiques of the all-male casting here mentioned that it’s got a dated aspect, and not dated in that it was happening 400 years ago, but dated in the fact that it was happening in 2000 at Shakespeare’s Globe.

Well it was happening in the 80s, it was happening in the 1880s, it’s an old trope, there’s nothing new about it.

MG: Well it was happening in the 80s, it was happening in the 1880s, it’s an old trope, there’s nothing new about it.

KP: It’s interesting you call it a ‘trope’. What do you mean by that?

MG: Well, all of these things are tropes in that sense aren’t they, the idea of replicating the original performance conditions of the 16th century Globe is a Victorian idea, no one had ever thought that might be interesting before that. But since then it’s hung around and there are now 14 replicas around the world. The idea of having all-female or all-male or cross-gendered casting goes back to the 18th Century in some cases and has found various degrees of prominence through the 20th Century.

KP: But the concept of all-male Shakespeare is receiving an increasing level of critique. So why do you see all-male casts as important?

MG: Well I think this actually comes back to what you asked earlier – are we a commercial company, and what does that mean, commercial? So in a strict sense, a commercial company is one that doesn’t receive public subsidy, and that operates as a limited company. And we are in that sense a commercial company. We don’t receive any public subsidy. In our opening season we received some sponsorship from ATEED, but it was a very small amount of sponsorship and it came with a lot of strings attached, which is fine, we were very grateful for it. But this season has zero public subsidy.

Are you saying that men onstage sell tickets more than women?

A commercial company is not subsidised by the state and that lack of subsidy limits its ability to take artistic risks. So working in this sector, the work we make is influenced by three factors. The first factor is that we make work for this theatre, which is in itself a fairly painstaking, although not perfect, approximation of a Jacobean Playhouse. So we don’t talk about authenticity – we’re not authentic. I think that’s a word we occasionally use, but we try not to.

KP: You use ‘accuracy’ more don’t you? As in ‘historically accurate’.

MG: Well, ‘integrity’. Within our company we talk about ‘integrity’. Work that has integrity.

So the second thing we think about it is that we have to make work for a theatre with 850 seats. That’s a lot of tickets to sell. And the third thing we have to think about is that we make work in that theatre by Shakespeare. So those are the three components that we have to think about.

KP: Are you saying that men onstage sell tickets more than women?

MG: No, what I’m saying is that in our first season we experimented with an all-male company and it sold a lot of tickets.

To be accurate – in our first season, we had one company of 16 actors but the 13 men in it made a separate show. So we knew that sold a lot of tickets last season. And I’d never actually made all-male work before, so we did it as a bit of an experiment for me, to see what it was like making some all-male Shakespeare. This season we’ve just done exactly the same as we did in our first season, except that we’ve doubled our output, so we have one all-male company and one mixed company. And they each make two shows.

MG: So the shows we make have to respond to those circumstances. If we’d returned to the space this year but made much riskier work…

KP: What’s risky in this sense?

MG: Well risk in this sense is making work that we haven’t made before. Work that we haven’t seen to be financially successful, by which I mean selling tens of thousands of tickets.

KP: But do you mean risky work is casting women as women and men as men – that’s surely not what you’re saying is risky?

MG: Well I would say to you that all-female work is slightly risky.

KP: Ah, I’m not talking about all-female work – I simply mean mixed casts.

MG: Well, one of our companies does follow that straight casting model, and the other one is obviously all-male. I don’t think it’s risky to make work that’s straight cast. This is why we’re not subsidised. We’re not a risky company. If people want cutting edge, they’ve come to the wrong people.

KP: And I don’t think that has ever been the angle within the criticism – that it’s not been cutting-edge enough. It’s simply that we’re now in a time in which we’re increasingly aware of theatre as a site of representation and that women’s perspectives are not as present as they should be.

MG: Really? I think they’re very present. In the shows we’re making at the moment, women’s perspectives are the driver.

KP: Yeah sorry – I’m not just talking about the Pop-up Globe, I’m speaking contextually. In New Zealand theatre in 2017, the range of women’s voices – in terms of playwrights being produced on mainstages particularly – is really low, and that has a flow on effect to women on stage. That’s the reality we’re dealing with and I think people are aware of that. So when you place an all-male company within that context for the second year running, it’s always going to be questioned.

MG: Is it? A lot of all-male work is made in New Zealand. Ben Henson directed three all-male shows in a row in Auckland and I don’t remember that being questioned. Was that questioned?

KP: He’s directed two and yes, I’m aware it was raised in forums around one of those shows.

MG: I don’t know, maybe.

I am a little concerned about questions of censorship in the arts.

I mean yeah, it’s very important for subsidised theatres to reflect society, and if I was in charge of a subsidised theatre I would be looking for a diverse roster of plays, playwrights and directors. Indeed, that to me seems to be the point of receiving public subsidy. I mean, if that’s not happening, then questions should be asked.

KP: I just think it’s interesting that you’re equating commercial success with having all-male companies onstage.

MG: No I’m not suggesting that. What I said is we made work last year that sold a lot of tickets, and we have repeated that this year.

There might be another question which is whether it’s valid in today’s society to make all-male work. But I am a little concerned about questions of censorship in the arts.

KP: Do you think that’s censorship?

MG: Well, I didn’t say that either. I said I am a little concerned about questions of censorship in the arts.

KP: Right.

MG: And I think that artists should be encouraged to make whatever work they want, with whoever they want, and we really shouldn’t seek to limit artists on any basis. And that means it’s okay sometimes for art to be very offensive – that’s fine, that’s actually quite good. It’s also okay for arts to be exclusive, and inclusive. Indeed art should be whatever the artist feels it should be.

KP: So one intention behind all-male casting is the commercial aspect, but surely there’s also a scholarship aspect?

MG: That’s why we do it, yeah.

KP: So what does that mean to you? What does ‘historical accuracy’ mean to you?

MG: I think one of the joys for audiences is in the idea of time-travel. So they take great joy in coming to Pop-up Globe and wondering what it might have been like to see the work made for the original Globe – the second Globe – 350 years ago. We know that Shakespeare wrote for an all-male company. We also know that many of his plays play with gender in very interesting ways, and that that play is deepened when certain plays are performed with an all-male company.

A case in point is As You Like It. The reason we’re doing As You Like It with an all-male cast this year is because in it there’s a character, Rosalind, a woman disguised as a man who goes into the forest, and while in the forest, pretends to be a woman. So there is a layer-upon-layer effect. And when you have that character played by a man, it deepens the effect, because of course you have a man, playing a woman, playing a man, who then plays a woman. And that is fun. It’s interesting. And it’s great art. Because art is about artifice, and illusion. And it’s about appearance and reality, and seeming. And so that’s an interesting artistic decision. And one that’s quite unusual to make actually.

You have a man, playing a woman, playing a man, who then plays a woman. And that is fun. It’s interesting. And it’s great art.

KP: You were just saying that it’s a trope.

MG: But it’s still fairly rare. The fact it’s been done for ages doesn’t mean it’s been done every year, so it’s still relatively rare.

So it’s interesting in Shakespeare’s work to cast all-male because it reveals otherwise unseen elements, of the text, of his intentions, unknowable though they may be. So that’s one reason for doing it, because we want to entertain our audiences and intrigue them with our work, and sometimes an all-male cast can do that.

KP: So it’s less about ‘historical accuracy’?

MG: It’s not really about historical accuracy at all. It’s always interesting to hear or see work made in the way it was originally made, in a simulacrum of the surroundings it was made for. Just as it’s interesting for music scholars to see music played on early modern instruments, it brings a certain understanding to the work, and depth. It’s the same for us, it brings a different understanding and a depth to the work. I think that’s interesting, and I think the response from our audiences indicate that it is interesting.

Publically criticising artists for the gender balance in their work, to me, is dangerous.

Should it be the only Shakespeare that’s made? Of course not. Should it be part of a spectrum? Well, why not? It would be a very boring world if we didn’t make all-female Shakespeare and it would be a very boring world if we didn’t make all-male. It’s a very boring world when we don’t let artists make the work they want.

KP: I don’t think people are stopping artists making what they want, I think people are questioning…

MG: Publically criticising artists for the gender balance in their work, to me, is dangerous. Because it can go both ways. It becomes a tool. It politicises work.

KP: Gender is political.

MG: Everything’s political.

I can tell you that it does make it difficult as an artist. Artists are sensitive people. And when their motives are questioned publicly and attacks are made upon them, it makes it more challenging for them to work. Particularly if it’s already extremely difficult to make.

KP: I think if the questions are about the nature of the work I think that’s quite valid. It depends on the intentions and the context behind the questioning.

I think if they’re just debasing the work in general, sure. For instance there’s a side of New Zealand popular culture that questions art in general for its supposed elitism. But I think when people are questioning the nature or the intention behind artistic decisions, well that’s art, we work in a realm that is hopefully constantly questioning those things. Do you not think?

MG: I don’t know. At the point when those questions were being made, no one was seeing the art we were making. So it wasn’t about the art we were making, it was about the gender of the people who were making the art.

KP: Well as I say, I think it comes back to the context of the New Zealand industry.

MG: I’m not sure what people want. Do we want to see more of a balance between the numbers of men and women who perform onstage? I’m not sure?

KP: I think it’s about industry and economics. I think it’s about women being paid. It’s about women having the opportunity to be paid in roles that were made for women.

MG: Well, that’s a very interesting aspect isn’t it. Of course none of those roles were made for women. But I’m nit-picking…

KP: Yeah, once again, we’re in New Zealand in 2017. Yes, they weren’t originally written for women but we are here, now, and they are women characters.

MG: But we do have plays that do that and we have other productions that don’t do that. So it’s a spectrum.

Like I say, as an unsubsidised theatre, it’s not the case that you can make avant-garde work and expect to sell tens of thousands of tickets.

KP: I’m not talking about avant-garde work. I don’t think that’s ever been a question.

MG: I think the question we’re hovering around is, “is all-female work avant-garde or is it mainstream” and I think that’s a question that only audiences can answer. I don’t really know.

KP: No, I don’t think that’s the question – you keep coming back to this all-female cast notion, and I don’t think that’s what’s been on the table. I think simply, mixed casts.

MG: Well, we do that.

MG: So this is where it’s a bit censorship-y. I can put it another way. There’s a trope of gender fluidity in contemporary Shakespeare productions which is a very interesting one – where certain lead characters are cross-gender cast. In recent times that tends to be male characters played by women. But oddly it can also reduce the author’s voice, which is usually a proto-feminist voice.

So there are wins that come with re-gendering or gender fluidity which are great wins, and there are losses too, and they must be balanced to keep making the best art. It would be absurd if we always had gender-fluid casting, and we always wanted to see equal numbers of men and women represented on stage. And indeed it would be a shame if the misogyny that is sometimes present in Shakespeare’s characters – although rarely in the author I think – is lost. Because part of understanding who we are is based on who we used to be. And sometimes art should make us understand how far we’ve come.

It’s better to let artists make whatever art they want.

So I think the simplistic solutions are not usually the best ones. And it’s better to let artists make whatever art they want. And if that work is offensive, then so be it. There must be diversity of voices. I think also, really interesting art is made from a point of view of adversity, as a reaction to other art. Art should be provocative – it should engender debate, if I can use that term.

KP: I agree. What would you say all-male casts are in response to?

MG: Well for me it’s in response to the author’s work. The opportunity to see that work in period costume, in an approximation of the original building. That’s an opportunity that would be lost if we didn’t have an all-male company.

KP: It’s interesting because you’re talking about art, and you’re also talking about being a commercial entity, so I’m interested in how you see those things living together. How do you balance the pressures of commerce with art?

MG: Yes, that's at the core of a lot of theatre. So, generally to make work that has wide appeal, someone has to be famous, whether it’s the playwright, actors, director, or the theatre maybe. Something’s got to be famous. In our case, it’s the building and the author.

That’s the true test – if people then see it and are moved deeply by it, that is when you will achieve success in terms of ticket sales, not before.

So you must make work that encourages the audience to put their hand in their pocket and part with their money. It becomes art when the audience is deeply moved or affected by what they see. That’s the true test – if people then see it and are moved deeply by it, that is when you will achieve success in terms of ticket sales, not before. So you have to make great art in order to sell tickets in high volumes.

KP: Do you hope to expand the creative leadership team in further seasons or do you think you’ll work with the same collaborators?

MG: I’ve made many projects and I’ve always worked with different people. And so we already have expanded that team – Miriama Mcdowell who was an actor with us last year has directed this year and we will continue to look to strengthen our team.

I think at core, it’s about personality. I understand the topicality of gender and I think it’s an important debate, but we’re all human, and our shared humanity must come before anything else. I think there’s a danger that we forget our common humanity and we perhaps begin to think that people of different genders or races or creeds can’t talk to or understand each other. But then we are denying ourselves an incredible opportunity as humans to connect with others and to work as collaborators.

KP: Do you see the Pop-up Globe as a New Zealand arts project? As part of the New Zealand arts ecosystem?

MG: Well I think it probably didn’t start as one perhaps. No, I take that back. Pop-up Globe is deeply rooted in New Zealand culture. It employs a huge number of New Zealanders, I’m a New Zealander, I grew up in Auckland. It was made in New Zealand, it was conceived by a New Zealander. All of the directors in the company are New Zealanders.

KP: The innovation…

MG: …is all New Zealand. And indeed it’s a project that couldn’t really happen outside New Zealand, because of its can do, number-eight-wire sort of mentality.

So, is it a New Zealand arts project? Absolutely. Is it about things that are only found in New Zealand? No. Is it international in its outlook? Yes. Is it a project that could have happened somewhere else? No.

KP: I think for me what’s so astounding about it, coming from a background as an actor, is that five months solid work as an actor is just so rare and quite incredible. And I think that offering, as a way of supporting the sector, is massive. So I think my question is less about nationalism and more connected to what it actually is offering as a commercial entity supporting the New Zealand sector. And in that way, it’s a significant element of the theatre sector ecology now.

MG: Yes it is. I mean 75% of our acting company are from here, we hold open auditions. I don’t think there’s many companies in New Zealand who hold open auditions.

You keep mentioning the word ‘commercial’, which I find interesting, because I don’t know why that’s important.

KP: I think you misconstrue when I use the word ‘commercial’ that I somehow mean ‘bad’. I don’t. I just mean that’s the nature of the project and I think that’s the exciting element about it; for a company to be contracting a large cast and crew in its second year is significant.

To see it made elsewhere would be an incredible achievement.

MG: Yes it is and it should be celebrated. We should celebrate independent producers who make work. But I think perhaps because there isn’t that ecology of independent producers making big-scale work in New Zealand, that it’s suspicious in some way, that someone would do that. And to me it’s a very natural way to work.

KP: What are your hopes for the future of Pop-up Globe?

MG: That we can continue to delight audiences. One of our founding aims has been to share the magic of the experience with as many people as possible and it would be wonderful to think we could continue to make interesting, different work here, and to take that work elsewhere. I said at the end of last season that I would love to see a Pop-up Globe in other countries and that remains an aim. To see it made elsewhere would be an incredible achievement.

KP: And finally, what have been some of your favourite moments this season, standing in the Pop-up Globe?

MG: That’s a very good question.

[Long pause]

I think one of the realities of running an organisation like this is that every moment contains both wonder and tragedy. So, very often…

[Pause]

Oh it’s quite difficult.

But, you ask me about my favourite moments, so…

KP: Where did you go?

MG: It’s a big journey. Working here. In whatever position. And very often the focus is on moment by moment delivery and pleasing our audience. So…

I’m not answering your questions. I’ll answer the question.

My favourite moments happen after every show. And it’s the noise from the audience after the show. And that noise is a loud, excited buzz of people who are talking nineteen to the dozen to their friends about what they’ve seen. And that buzz is probably the greatest tonic you can have running a theatre because it’s the sound of people who’ve had a great time.

And there’s a line in Twelfth Night that the character Feste says in the epilogue, the song, where he says, "we’ll strive to please you every day". And that is what we do. Every day we strive to please.

The Pop-up Globe are hosting a brief panel discussion titled All-male Shakespeare: Historically Accurate or Sexist this Tuesday 2 May on the Pop-up Globe stage.

For more information and to RSVP, head to the Facebook event page.