Vigilance Against Laziness: A Conversation with Elizabeth McCracken

Kirsti Whalen talks to prize-winning author Elizabeth McCracken about craft, writing education, and proving yourself through hard work.

Kirsti Whalen talks to prize-winning author Elizabeth McCracken about craft, writing education, and proving yourself through hard work.

I came to Elizabeth McCracken’s work as I’ve come to all the most wonderful things I’ve read: by recommendation. My best friend was completing her Master of Fine Arts in fiction at the Michener Center in Austin, Texas, where McCracken currently holds the James Michener Chair. My friend spoke of this teacher of hers like a person in the first grips of seduction. From the other side of the world, she told me that I would love McCracken, that I must read her, right away.

When I discovered that McCracken would be speaking at this year’s Auckland Writers Festival, I found myself as excited as when I was reading the first few pages of her astounding memoir – not least because I had the impression that McCracken was as much teacher as author, powerful and commanding in both roles. A New York Times review of her latest book, the short story collection Thunderstruck, refers to its “scratchy humour and warm intelligence,” which I imagined might describe McCracken too. The review goes on to say that her writing employs the idea of mourning “to show us, again and again, just how proximate joy is to its antithesis. ‘This is the happiest story in the world with the saddest ending,’ McCracken writes in her memoir. In this restorative, unforgettable collection, she allows that paradox to go both ways.”

McCracken did not disappoint me. Though she’s been shortlisted for and won numerous awards, she speaks with unassuming generosity. There is an innate kindness about her, as there is about much of her work. It’s hard not to rave about Elizabeth McCracken. I hope that most of us have had that one teacher, the one who changed our lives for the better. For the 45 minutes of our conversation, I think McCracken was mine. We spoke about craft, about writing education, about vigilance against laziness, and about how – as McCracken has herself shown in her memoir, short stories, and novels – perseverance is something you can prove, over and over again.

*

KW: When did you start writing?

EM: I was pretty much one of those kids who always wrote something, although for a long time it was mostly poetry. My brother was a very good cartoonist and drawer and I was not, so I think I started writing things at a pretty young age so I could have a distinct way to show off. And then I began to write more seriously in college, later in college, and went to graduate school for fiction right afterwards.

KW: So you did an MFA program?

EM: I did, at the Iowa Writers Workshop.

KW: It’s interesting with education in creative writing … In New Zealand we have a relatively long tradition of it in one place, but it’s only just started to infiltrate as a national concept.

EM: Oh that’s interesting. Is that in Wellington?

KW: Yeah. Wellington is the place where it’s been going on the longest. Bill Manhire started the course there. I’m actually doing my MA there at the moment. But elsewhere in the country, it’s relatively new, and I’ve heard a lot of questions asked about writing education and what the potential outcome of it is. Coming from a country that has had a longer history of teaching writing, do you think there are any problems with the structure of going to university to write, or do you think it’s wholly positive?

EM: There’s nothing in the world that’s totally positive! I certainly know people who went to study writing and it was terrible for them, and I really am one of those people whose MFA programme really made them a writer. I don’t think it taught me to write, and I don’t think that when I do this I teach them how to write, especially because any rules I have regarding my own stories aren’t going to be applicable directly to somebody else’s. But what you get when you study writing, I think … Certainly the thing I got from my teachers is that they got me to think really interesting thoughts. They got me not to be lazy. They got me to be really impatient with the things that came really easily to me and to attempt the things that were hard for me. They read my work and pushed it forward in a way that I think I wouldn’t have if I was just writing by myself.

To me, graduate school taught me ambition, which I don’t think I had before. Like I said, I like showing off. That was the aspect of writing I was interested in when I was younger and I didn’t understand that sense of being ambitious, because I wanted to write the best possible thing, whether I was going to turn it in for a class or not. I think one of the things that can be problematic in studying writing is if you are with a teacher who reads your work and is really insistent on telling you what will make it publishable, because that’s a smaller ambition than writing the best story that you possibly can. And I think, deep down, nobody really knows what’s publishable – if you look at the books that become huge successes, and if you describe them, you wouldn’t you say of any of them, “Oh, that sounds like it’s going to be a big hit!” It’s strange and idiosyncratic.

KW: I think there’s an interesting tension as well in writing education – not that I’ve ever taught it – between the idea of talent and work. I think when talent is actively rewarded in programmes maybe it’s not as productive as that idea of ambition.

EM: I really couldn’t agree with you more. Because talent alone doesn’t get you anywhere. I graduated from my programme 26 years ago, and the people who have been most successful are the people who have kept writing, not the ones who were necessarily the most talented. And – I’m kind of obsessed with this because I have a little kid – every study of kids says it’s really bad to tell children that they’re smart. It’s really good to praise them for working hard because smart is static. All you can do if you’re told that you’re smart is disprove that you’re smart. But if you’re told that you work hard, that’s something you can prove over and over again. It’s something I think about with my students. Even if I think someone is really talented, it’s a word I’ve tried to stop using, because I think actually it can terrify people. It’s not beside the point, but it’s not as important as work.

The people who have been most successful are the people who have kept writing, not the ones who were necessarily the most talented.

KW: One of the issues here, I think, as a postgraduate writing education grows, is this issue of diversity. Which is such a loaded term. But a lot of programs thrive on the basis of being elite and proposing that they are the best. I think maybe people don’t apply who aren’t commonly acknowledged to fit within this certain realm of what a ‘writer’ is, and we even end up with a voice that is a little samey. Everybody sounds the same, because they all come from a similar background, despite a diversity of experience. They’re all writing towards the same canon. Do you think that’s an issue in the states?

EM: To me, when I’m reading applications for graduate school, I really want a diverse group of people. It may be that because we have a long history of it, it seems that there has been a real change. In the last 15 years or so, when I’ve read applications for various places, the group of applicants has become more diverse, because it no longer seems like a pie in the sky kind of thing. Also, at least here, it’s very circular, in that I had an undergraduate who was in my class who was born in the States but her parents were immigrants from India, and she went to see a former student of mine from graduate school, a wonderful writer who is African-American. She wrote a response to that reading, saying how important it was for her to see a woman of colour reading and writing and being excited about literature. It’s one of those things – the more diverse programmes become, the more diverse the applicant pools are. And it’s important to me because I want to have students who have a variety of material and a variety of world views and techniques, so that the work isn’t all the same. I feel like I want to make sure that I’m not … If everybody’s a similar writer then it’s hard to learn from one another.

KW: Do you think in that respect that it’s worthwhile dividing people by genre: poetry, fiction, non-fiction? I think this is especially interesting because you’ve worked across different forms … Do you think it’s productive to divide according to mode, or do you think just throw everyone in together and see what they learn?

EM: At the Michener Center you have to study two genres, a primary and a secondary. I had lunch today with a student who talked about how much she learned from playwriting. I have to say, in my ideal world, yeah, it seems like a very 20th century and onward idea that you have to specialise in a particular genre. As an undergraduate, I studied poetry and playwriting very seriously and even though I don’t write either one of those things any more, I’m really aware of what I learned from them. I also think the more ways you work your brain, the more interesting your writing will be. I read a lot of poetry, and I go to a lot of plays as well, and I’m very aware of being a good consumer across genres. It’s inspiring and important to me.

The more ways you work your brain, the more interesting your writing will be. I read a lot of poetry, and I go to a lot of plays as well, and I’m very aware of being a good consumer across genres.

KW: I’ve just been reading Thunderstruck, and I think your short stories are astounding. Have you always written short stories or was there a particular impetus driving that project?

EM: Thank you. It was a bunch of failed novels! The funny thing is, my first book was a collection of short stories, and then I wrote two novels and then a memoir, then a bunch of failed novels. And there was this big part of me that thought, “Oh, maybe I’ll never write short stories again,” because they were very important to me to read, but I began to think about how hard it was to write really great short stories, and I thought about the people whose stories really meant something to me. But then I sort of bumbled into a bunch of failed longer projects and took real pleasure in writing short stories. And now I can’t believe that I thought I wasn’t going to write any more.

I also think it’s interesting that I was teaching during this time, and some of my students write novels, but by and large what I’m reading is short stories. And I suddenly realised that I have all these theories about good short stories I had developed in reading and commenting on … I was going to say hundreds, but I’m sure I’ve probably read thousands and thousands of short stories in the past 20 years. Actually, there’s no doubt I’ve read thousands and thousands. And the theories I had were actually really useful for my own work, and I hadn’t had them the last time I seriously wrote short stories. I hadn’t thought about them. But even without realising it I had been thinking about writing short stories over the last couple of decades, I just hadn’t been doing it. Or hadn’t been doing it very often.

KW: It strikes me as really interesting – but also kind of terrifying – the idea of failed novels. I know a lot of people who have poured so much energy and time, and indeed financial resources, into writing a novel. But did you ever have the fear of not completing a book-length project and do you ever find that somehow limiting?

EM: I’m pretty tough about it. And whether this is more terrifying or less terrifying to you, I finished all those books. I wrote more than one draft of them. I think it would be harder to walk away from them if I hadn’t done that. I had a whole object. And there were three of them. One of them, the minute I walked away I understood that I was never going to get it. I asked someone, “If I get this book right, will it be a great book or a pretty good book?” And he said, “Well, I think it’ll be a pretty good book.” And I thought, I don’t want to write that. When I gave it up, I felt a huge sense of relief. There are three stories in Thunderstruck that have their genesis in that novel. They don’t resemble the versions that they were in that novel at all. They have different kinds of narrators and narrative tricks.

The middle one that I gave up is still kind of painful and I haven’t looked at. The third one, I had leave from my university job and I wrote a bunch of the stories that are in Thunderstruck, then I had some time left over, so wrote two fourths of a novel and wrote the other two fourths over the next few months, and that one was a failure. You don’t write a good novel when you suddenly think, “Oh, I have some spare time! I think I’ll write a novel!” I’ve had it in my head and sort of marinating, and I think I’ll do something with parts of it, but there was something about it as a book … That one gives me no pain at all. I just walked away. Sometimes I go, “Oh yeah, there’s that character in that book. I liked that character.” But the middle one I’m still a bit tender about.

You don’t write a good novel when you suddenly think, “Oh, I have some spare time! I think I’ll write a novel!”

KW: So a failed novel is always one you walked away from, rather than publishing being a marker of success or failure?

EM: The third one I didn’t even try to publish. I gave it to two people to read and they were like, “Yeah, it’s all right. I think it needs a lot of work.” And I was like, “Oh, that’s interesting. I don’t want to work on this any more!” So that was definitely one that I just walked away from. There’s some intersection with the publishing world, but in no case, with none of those books did I finish it, send it out to a bunch of publishers and they said no. There are many stories of brilliant novels that went out to a million places and everyone said no until the right person found it. I have a really good sense that none of those novels is that kind of novel!

KW: It sounds like you have quite a thick skin. Or maybe just a realistic attitude to your own work.

EM: I think that’s fairly true.

KW: I think a lot of people are perhaps less pragmatic.

EM: I’m definitely not precious about my work in any way.

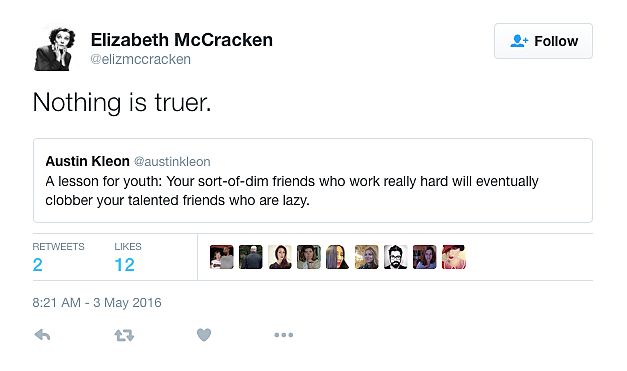

KW: Speaking about not being precious about things that might end up in public, I’ve seen that you have a relatively active Twitter profile. I’m really interested in writers on Twitter, what that’s like, and what kind of purpose it serves in various peoples’ lives.

EM: I really enjoy Twitter. I wouldn’t use it if I didn’t really enjoy it. I think when social media gives writers fits is when they don’t enjoy it, and I don’t think there’s any value in the kind of miserable self-promotion you can see some writers do, in which they get a Twitter profile when they have a book coming out and then try to sound sort of casual, like, “Oh, I’ve got this book coming out!” I am probably unhelpful to myself – I really never promote anything. Occasionally, I will say I’m going to be reading, but I can’t – and I don’t disapprove when writers do this – but I can’t tweet reviews, and I would never. Some writers are very good at tweeting every piece of praise they get, and I have never done that.

I like Twitter because I like short form. It’s like tiny, short form writing – like fortune cookies and one-liner jokes. I really like making jokes, and I like talking to strangers. It’s sort of like bantering with people. I enjoy it. It’s surreal and strange. You can throw out an obscure reference and … If you were in a crowd full of people and you threw out an obscure reference and only one person got it, it would be a failure. But if you do it on Twitter and one person gets it, it’s a huge success.

KW: Can I ask how you juggling teaching, writing, and family life? Do you have a rigorous structure around writing time?

EM: You know, I don’t. I used to get almost no writing done during the semester and I’ve just started getting more done. That might be because my kids are now older. I’m married to a writer and professor and so we’re pretty fluid about giving each other time, and we absolutely share all childcare stuff and that gives me an enormous advantage over a lot of writers. I tried for a while, last fall … I thought, “This is it. I’m going to write every day from eight till eleven.” And I discovered that I cannot write anything from eight till eleven. Sometimes I get out of bed very early, like four thirty or five, and sometimes before I talk to anybody I can get work done, and then if I grab an hour and a half in the afternoon, I switch off the internet and can get work done then. But for some reason, eight till eleven is not a time where I get anything done.

Unless I was on a giant work bender and was working eight hours a day, which I’ve done in my life … But even then, I probably wouldn’t be doing real work from eight till eleven. I try to be, as much as possible, vigilant against laziness. And I try – if I’m working – to take an extended break from Twitter. The thing I like about Twitter is that it can be a kind of valve on the day, to relieve a bit of brain pressure, but if I’m working on a novel, I need that brain pressure. I need to siphon it back into the work.

KW: Would you be willing to talk about what you’re working on at the moment, or is it a secret?

EM: No! No, I would not. Part of that is just having walked away from a couple of novels. People have asked me, “What ever happened to that weight-lifting novel you were working on?” And I’m like, “Arrrghhh, uggghhh.” So I tend to be pretty vague about it. I’m pretty close to having a first draft, though. I’ll take a look and see what it looks like. It’s a novel. I’m working on a novel.

KW: It’s funny, with the Masters course I’m doing – and maybe it’s the same with the MFA structure – something I’ve struggled with is that I hate telling people what I’m doing but you have to! You have to share it with the whole workshop group and you have to have a supervisor and I’m like, “But it’s a secret! It might fail!”

EM: Right! Yeah.

KW: Do you decide before you go into a project what it’s going to be – short stories or a novel – or is it really obvious? Does it just happen from the content?

EM: It’s always really obvious to me, but it might just be a trick of the mind. When I’m working on a short story, I know it’s a short story idea right away. But when I’m in the middle of a novel, I rarely get short story ideas, because I think, “Well, that’ll go into the novel, and that’ll go into the novel.” I have, while working on this novel, written two short stories. But I haven’t stopped working on the novel. When I’m traveling, I’ll get an idea for a short story and I’ll write the whole short story. But I cannot be working on two things at once. I couldn’t even tell you what the difference is … Well, one of the big differences is that I have to have a greater emotional investment in novel characters than I do in short story characters.

KW: I guess because you have to sustain them over a much longer period.

EM: You have to spend that much more time with them, so there has to be a certain mystery at their heart that you’re interested in exploring. And I feel like you can write a short story character who’s a really well-rounded short story character, but if you try to put them in a novel, they’ll crumble to dust, because there’s not really enough to them.

You can write a short story character who’s a really well-rounded short story character, but if you try to put them in a novel, they’ll crumble to dust, because there’s not really enough to them.

KW: I write non-fiction, so I’m particularly interested in your memoir. I loved it. I wanted to ask whether you had any fear in putting something quite vulnerable into the world?

EM: That was a very weird book. For a lot of reasons. And the big one was that when I was writing it, I didn’t think I was writing a book for publication. I knew I was going to write about the experience at some point. And then when Gus, my second child … I said I was not going to write during my pregnancy at all. And then Gus was born, and I was really interested in getting down what I felt then. I knew that if I waited a year to write something, it would have shifted. And the emotions … I wouldn’t have been able to get them on to the page. So I wrote what I sort of thought was notes for a novel.

Adding to this was that when my first child was stillborn, that day there was an article in the New Yorker, a beautiful article by a writer named Daniel Raeburn about his and his wife’s child, and in my mind, weirdly, I said, “Okay, that essay has already been written. I’ll take this to a novel.” And I wrote it very quickly, in about three weeks, when Gus was a baby, about three weeks old to six weeks old. I finished it and I looked at it and decided I was going to send it to my agent. I gave it to my husband and he read it and he said, “Yeah, that’s what happened. I can’t give you any other information about that.” I told him that I was writing it and I did not tell another soul that I was writing it.

I sent it to my agent and I asked, “Do you think this is a book? Because if you think it’s a book I’ll work on it a little bit more, but if you think, ‘Oh, this needs a lot of work,’ I’m not going to work on it any more.” Because it was very important for me to write, but I didn’t think it was very important for me to revise. Interestingly, when it went out to publishers … Well, if you think I’m practical around my fiction, you should have seen me around that book! I was like, “Listen, you’ll want to publish the book, or you won’t. If you give me notes on the book, chances are I’m not going to take them.” I mean, I was really cast iron on the subject. And I can’t imagine I’ll ever write another book that will resemble it in any way.

If you think I’m practical around my fiction, you should have seen me around that book! I was like, “Listen, you’ll want to publish the book, or you won’t. If you give me notes on the book, chances are I’m not going to take them.”

But for some reason – I’m not sure if that even answers your question – for the most part, when I publish something, it really stops being personal to me. The information in it obviously is very personal, but the book itself … it’s fine, it’s outside my body. I don’t think about having written it. And I feel like I made up my mind that I was going to publish it, and that was a decision I only had to make once.

KW: I’ve written some pretty personal stuff and have published it, not in book length, but still the major response that I’ve had is that honesty is brave. I guess I agree with that to an extent, but I wonder if what you’re saying aligns somehow with my belief that it’s not necessarily bravery. It’s kind of catharsis and necessity coupled with, for me, just a commitment to writing and this idea of what writing is. I’m not making much sense, just trying to …

EM: No, but that is how I feel. That “Oh, wow, that’s really brave,” that’s a statement about the speaker, not a statement about you. It’s them saying they have a different relationship to honesty, perhaps. I don’t believe in writing as therapy, but at the same time there is no doubt in my mind that writing that book helped me organise what seemed like formless, terrifying emotions, and I got them on to the page and I was like, “Oh, no, those are fine. I can live with everything that I felt.” Writing it was like this really important organising experience for me.

KW: There’s a passage in the first short story in Thunderstruck that talks about grief, and says that the things you’re allergic to can walk through walls, and I was thinking that though it isn’t in memoir form, it could almost slot quite happily – different voice – into the memoir. It’s the same sentiment. But people wouldn’t call that brave, they’d call that good writing. Or at least I would. There’s this critique of personal writing that perhaps is more personality-based than about craft or ability.

EM: I think you’re right.

KW: You said that you felt that the New Yorker piece meant that the story had already been written. Has every story not already been told? And we’re rehashing?

EM: Absolutely. It was a very bad time in my life, and I think it was really useful for me to think … I think what happened was that my defence mechanism told me I’d write about it. It was just a matter of timing. When I saw the piece, I was not emotionally myself, and I was like, “Oh well, I guess you’re just going to have to feel this then.” And then by the time I was ready to write about it, it had shifted. It wasn’t that I actually thought that if someone had had a similar experience to me then there was no writing about it. It was a weird little trick that my brain did, totally out of self-preservation.

KW: But I think it is an idea that comes up for people, when you starting thinking you’ll write a book and start reading in the same area. It would be very easy for people to be put off by the idea that someone else has already done it. And potentially done it better.

EM: Oh, I think we’re all terrified of that.

Main image: Elizabeth McCracken. Photograph by Edward Carey.

Elizabeth McCracken

Auckland Writers Festival

10 to 15 May 2016

Aotea Centre, 50 Mayoral Drive