Internet Histories | 2 June

This week on the internet: Joe writes on the ethics and practicality of ubiquitous trigger warnings, and Matt visits the newest library in the world.

This week on the internet:

Trigger warnings | The newest library in the world

Joe

Oberlin College was the first institution of higher learning in the United States to regularly admit women and black students. It has one of the largest and most effective student co-operative movements of any North American campus, and it’s ranked as one of the most LGBTI-friendly places to study in the American Midwest. They’ve even banned Coca-Cola products from being sold on campus, which is probably pretty minor in the scope of things but points to an effective student body and a receptive staff.

So it wouldn’t be that surprising to learn that faculties provided things like content advisory warnings to students for lectures that contain difficult or upsetting material, right? Actually, it’s been a bridge too far. A draft policy circulated online this year has been hastily retracted, as the New York Timesreports:

The guide said they should flag anything that might “disrupt a student’s learning” and “cause trauma,” including anything that would suggest the inferiority of anyone who is transgender (a form of discrimination known as cissexism) or who uses a wheelchair (or ableism)…

For example, it said, while “Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe — a novel set in colonial-era Nigeria — is a “triumph of literature that everyone in the world should read,” it could “trigger readers who have experienced racism, colonialism, religious persecution, violence, suicide and more."

Online, these “trigger warnings” are nothing new, and a cursory bit of Internet archeology suggests they’ve been around for 20 years. The idea that our content should be flagged is nothing new either, though until recently it took the form of a kind of moral prissiness – the fear of a bollock, a “fuck”, or a corpse on pre-watershed television. Spoiler warnings made the transition to popular usage even earlier, and it’s always a source of mirth to see a bunch of educated adults jeer at the idea that watching a rape scene in a movie might induce PTSD in certain people only to throw minor tantrums if they learn a fictional character dies in a fantasy show before they’d caught up.

I’m not that invested in the efficacy or otherwise of a trigger warning, because I’ve lived an immensely fortunate and comfortable life free from abuse or hardship. My preference is to deal with people experiencing PTSD at face value and assume that if they want some prior warning before being confronted by something that reminds them of something horrible happening to them, they should be extended that common courtesy.

I’d also rather hear about this from people who teach. Here’s Inside Higher Ed, with Angus Johnston writing on why, and how, he’s adding a trigger warning to his syllabus. It’s hard not to read it without thinking “there, that wasn’t so bad, was it?” On the other side of the coin, this essay by seven humanities professors is the best series of arguments I’ve seen against trigger warnings. Although when you read it, it’s less about trigger warnings being nonsense and more about the insufficiency of them. Trigger warnings before an assigned reading don’t protect you from sounds, textures and colours. Trigger warnings aren’t a substitute for effective pastoral care at colleges, and heaping more of this onto academics who aren’t trained professionals is a potential trainwreck. Their alternatives are quite good.

They’re also worried about getting totaled by a flood of complaints, though they’re not treating it like the apocalypse some commentators have. Ultimately, alarmists are putting forward this idea that there’s some enveloping, overcoddled hypersensitivity that individuals only developed in the past few years. They’re also suggesting that these precious little petals will demand trigger warnings for Michaelangelo’s David, that they’ll inundate college processes with endless complaints against their lecturers, that they’ll file civil action against their universities for the emotional distress.

It’s hard to see this as anything other than a reaction to how previous moral panics were handled – the way a banker in Knoxville launched a class action on behalf of all American citizens for being offended by Janet Jackson’s nipple in 2004, or inquiries by school boards into Dungeons and Dragons being played in libraries. This shows that if anything, we’re less histrionic about stupid things than we were a decade ago.

It also assumes that people who are triggered by particular experiences are also going to be litigious and difficult – I think this person’s reaction is unreasonable, so everything they do will be unreasonable too. And I just think that’s untenable, really. Every institution has to deal with its share of pathological complainers, and it’s unfair to tie that in to what seems like a pretty minor tweak to the syllabus, and one that I’m yet to see would cause more harm than help were it done well.

Matt

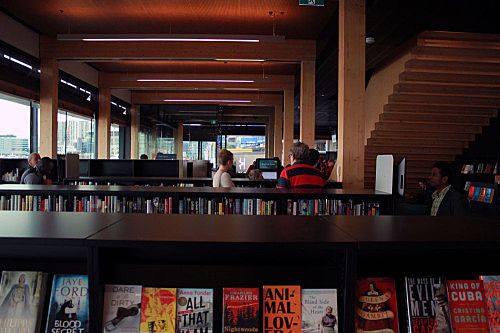

On Saturday afternoon I visited the most modern library in the history of the human race and got the distinct impression it didn’t know precisely what it wanted to be.

When I heard that the state-of-the-art library that was being built in Docklands, a commercial inner-city suburb of Melbourne, I was honestly confused. It would be like building Xanadu next to Albany Mega Centre, if commercialism were going out of fashion: a nice thought, but kind of beside the point? Things I did not count on include:

- Floor to ceiling views of Melbourne harbour

- A recording studio

- Hundreds of thousands of new books

- Reclaimed timber walls, floor, everything

- Virtual reality computer terminals

- VIRTUAL REALITY COMPUTER TERMINALS

- The goodwill of a million hippies

- A table tennis table

But, but, declining borrowing numbers! An expired mandate! Tired, redundant stacks! Apparently not.

My mum visited our local library to borrow the sorts of books she enjoyed reading. This was, of course, before one could simply download them online – otherwise I would have done so for her, teaching her to torrent her favourite authors as I later taught my friends how to steal their favourite TV shows. Or would I? Half the fun, in those early years, was in discovery: you thought you knew what you wanted, but by serendipity you ended up with something else extra, some author next-door. I discovered a million things I wouldn't have, crouching and stretching between tall tiers of regimented timber pulp.

Back in the 90s, books were still readily divisible units of a culture that moved on a scale of years or months. Today, culture lives and dies tomorrow or the day after, and taking even a couple of months off the internet means hopeless obsolescence. I suppose that’s why the libraries of modernity are creatures of open-space plans, of multi-use spaces and cultural convergence. I guess it's why the Oculus Rift and 3D printers fit sensibly next to the more familiar book; if a library is foremost a place of intellectual discovery, these new machines make sense.

This most recent creature was an incredibly pleasant, warm, deep place to relax inside (screaming first-day children notwithstanding). It was eco-friendly in a way that wasn’t a platitude, and multi-purpose in a way that didn’t mean ‘future community hall’. If this is what it means to be a library in the twenty-first century, count me in.

Elsewhere:

The writing life: optimizing revision

Why people believe things that are provably false

Humans are shit at thinking about privacy

New Zealand documentary shorts

Key Shawshank Redemption scene overdubbed with Smashmouth