Interlacing Whakapapa

Sinead Overbye weaves her whānau stories and poetry together in response to video work He Waiata Aroha.

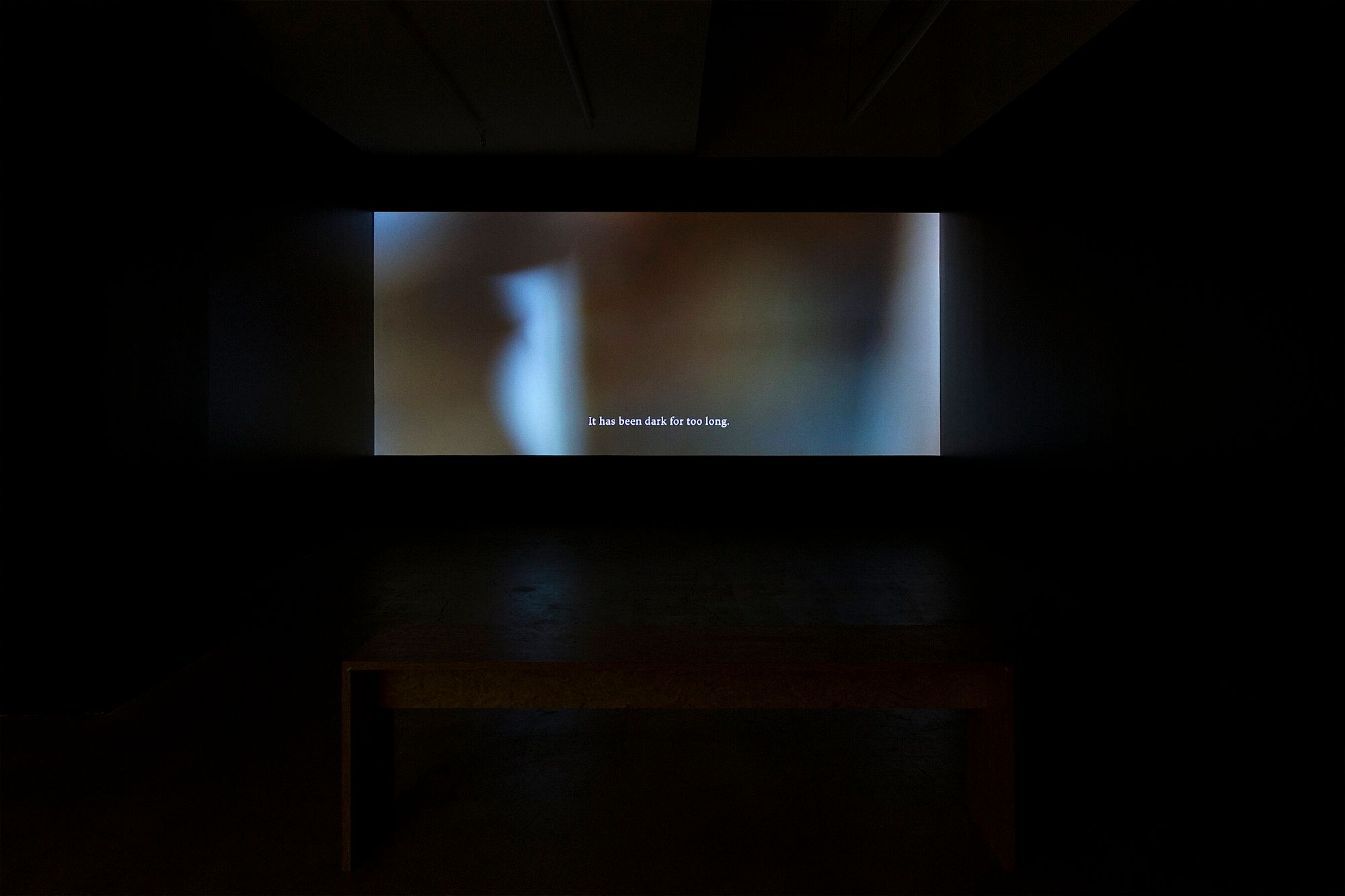

He Waiata Aroha is an entrancing and evocative video work by James Tapsell-Kururangi (Te Arawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Mākino, Tainui, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau-a-Rākairoa), installed at Enjoy Gallery in Wellington during April and May this year. The video itself is just over eight minutes long and is truly transportive – it picks up your entire heart and wairua and takes you on an emotional journey. The work didn’t just sit on the screen; rather it encompassed me, filling the whole space, projecting right into my psyche.

+++

We walk into a room where the video work is being screened and are called in by a voice reciting a waiata aroha. It calls all of our ancestors and descendants in too. We sit together, watching the images appear on the screen – a table with two empty chairs, the view of a path from the window of a whare, and other less distinguishable images – made up of blurs, textures and light, they evoke a feeling. Still we can’t see clearly what they are. They are all emotion.

The footage in He Waiata Aroha centres around two places – Tapsell-Kururangi’s nan’s house and the Tongariro River, where his great-grandfather drowned. These are sites of memory and of oral histories, passed down through generations. The stories associated with both places are present in the work, yet the specific memories and feelings are unknown. In these two settings, he captures place and at the same time obscures it from our view. This feels like a memory. It also feels like a barrier of tapu. He is protecting the memory of his tūpuna, and their mana.

James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

There are snapshots of my nanny that I remember. I remember her hands, arthritic and laden with rings, which she’d cheerfully chink together as she clapped along to the music. I remember her electric La-Z-Boy, which we’d clamber onto when she wasn’t in the room, pushing the buttons on the remote to flip our legs up and down, like a carnival ride. I remember the photos of our tūpuna all over her whare – her sitting room a memorial to her loved ones. I remember her collection of novelty porcelain teapots in the shapes of heads or houses or animals. The cream crackers and jam in her kitchen cupboard. The lavender smell of her bathroom. The shuffle of her slippers on the lino floor.

When my nan got dementia, I began to conceptualise memory as a fragile thing that could be broken. I remembered less and less how she was before, and she remembered less of me.

*

Tapsell-Kururangi speaks about being drawn back to the Tongariro River again and again. Through the footage, the way the light filters in, the stillness and the closeness of objects, we can wonder: Why this place? What are my ancestors trying to tell me? Why have they brought me here?

When I was young, I heard stories of the Tūranganui River, flowing through my hometown of Gisborne. That river guided settlers in from the oceans, which they’d travelled for a long time in search of Terra Australis. When at last they came across New Zealand, Cook and his men shot and killed Te Maro, a prominent rangatira, on the banks of that river. The next day, Cook returned to properly greet the people he called ‘Indians’. They stood atop Te Toka-a-Taiau, a rock in the river channel, and shared a hongi. That rock, which was so significant to many local iwi and hapū, was blown up in 1887. When Cook left Te Tairāwhiti, he renamed it Poverty Bay, as it offered him and his men “no one thing [they] wanted”.

The histories of the Tūranganui River live on and permeate the city. There’s an ancestral pain, a historical sadness, to that place. In 1865, my own ancestor Thomas Halbert drowned in that river. I’ve been able to trace multiple ancestors who’ve met the same fate, having died in the same place. What do these rivers remember that we might not? And how might remembering these ancestors shape our relationships to these places?

*

I’ve been reflecting lately on our histories. I use the plural consciously and deliberately. We are plentiful, each one of us, in and of ourselves, and we carry a multitude of our own stories and heritage with us. I am made up of every experience and story I’ve been taught and every person who has influenced my life. You are made up of every experience, story, and person who has influenced yours.

I think the most interesting histories, and the ones that hold my attention, have always been those that are closest to me. When I learn about my tūpuna, when I hear their stories, I am launched back into the past in the best way. I am able, then, to truly know them. And the more I know, the more connected I am to my whakapapa and my identity. This is true of all my ancestors – Māori and Pākehā. The more intimately I come to know them, the more comfortably I can sit within myself.

Tapsell-Kururangi’s work reminds me of the importance of histories, of being able to look back and know ourselves, to have relationships with our tūpuna that stretch across lifetimes and generations. To allow them to guide us and to trust that they’ll always be there.

*

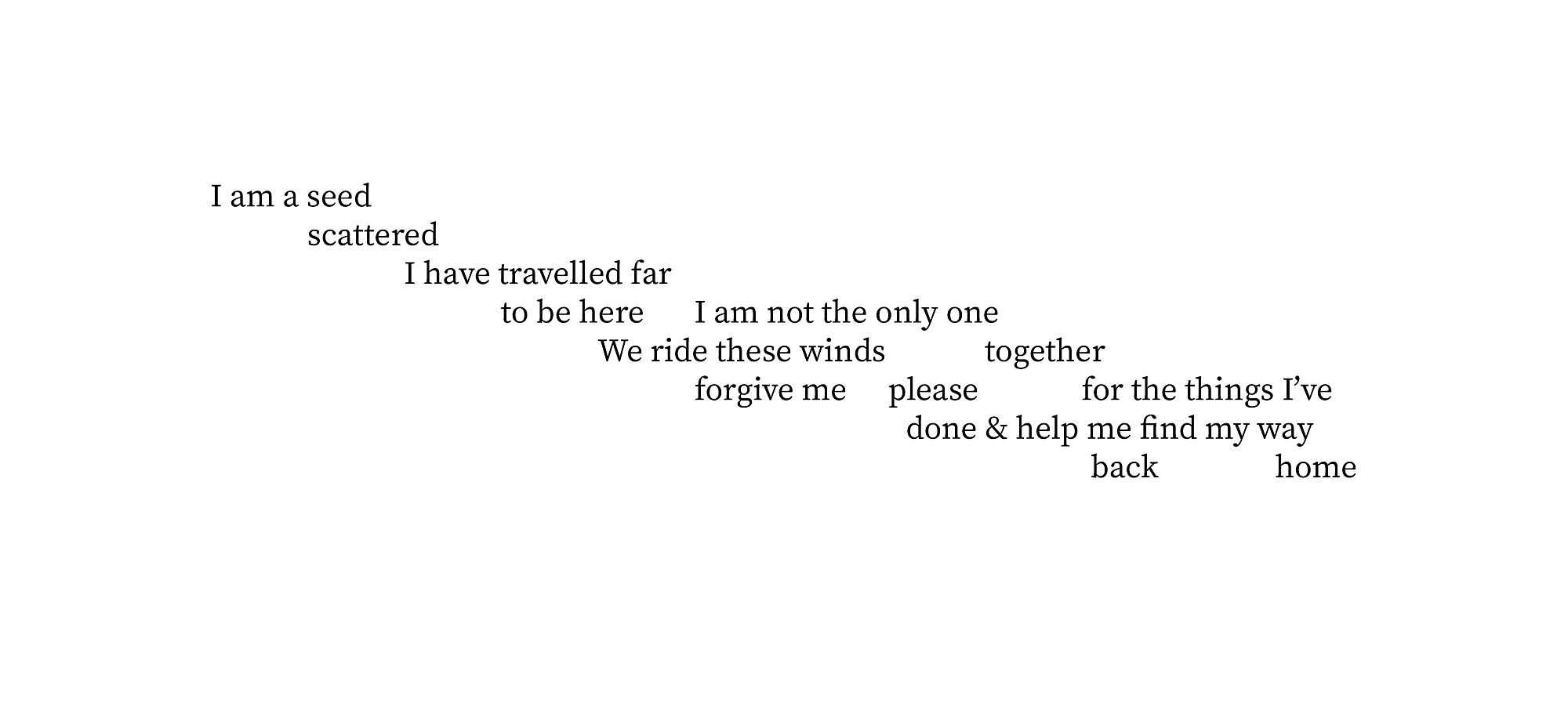

Accompanying the imagery in He Waiata Aroha is a poem and love song. The juxtaposition of image and words entrances me. I turn to ask my partner, But who do you think is speaking? They say, I think it is our tūpuna, speaking back to us who are living. We wānanga about it briefly, in that dark room, with the voice starting to sing its waiata aroha.

James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

After mulling over it, I decide the voice isn’t just our tūpuna speaking to us. It is also our older ancestors speaking to our grandmothers and great-grandfathers just before they passed. It is an entire community of tūpuna speaking to an entire community of descendants. But it is also the house of Tapsell-Kururangi’s kuia, being given a voice. It is Te Rā. It is Māui and his brothers. It is whoever we imagine it might be, or whoever we might need it to be, speaking back to us. It is also us speaking back to them.

+++

There is so much that I don’t remember of my kuia. I hear about her in stories, my great-aunty recalling how they used to laugh and ride horses and sleep under trees. I hear about her as a young woman. How when she first met my grandfather, he told her how well she could play the piano, and she said, “Well, that was it,” and married him not long after. I hear about how she was as a mother. Sometimes others will tell me things she said, or thought, or believed in. They’ll say to me who she was. How the day I was born, she met me. How she used to answer her door at midnight, take me from my crying mother’s arms, and I would instantly fall into a peaceful sleep. There is so much I don’t remember, but that is the nature of oral histories. I get to have all these stories, and they become a part of my body of knowledge. They become a part of me.

+++

Grief is a complex process and is always culturally bound. For me, I believe that my tūpuna are constantly with me, even after their passing. I believe that our relationship continues when they depart te ao kikokiko, the world of the living. Our ancestors travel at night, and when I need them, they keep coming back to visit me.

For years, I believed I would never see my nanny again. But now I find her all the time, in the smallest places. I find my great-great-great-grandfather, too. And all my ancestors, all the time, they travel with me.

*

He Waiata Aroha is a triumph. I watched it and re-watched it, and in every instance of watching, I thought of different things. Sitting in a room and remembering and conversing with my loved ones who had passed was so valuable. We need more time to do this. And we need more room to express our grief. To sit with our tūpuna and get some guidance. And to let ourselves be guided by them. James Tapsell-Kururangi has created a gorgeous song of love to his tūpuna. There’s no doubt that they are proud of him.

Feature image: James Tapsell-Kururangi, He waiata aroha, 2021, single channel HD digital video, 08:12. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.