Far From Vanity: Six Profiles of Independent Aotearoa Authors

Antony Millen challenges the stereotype that authors who publish their own work are vainglorious, or a lower class of writer.

Antony Millen challenges the stereotype that authors who publish their own work are vainglorious, or a lower class of writer.

In previous ‘indie roundups,’ The Pantograph Punch has featured new books produced by independent publishing houses. These houses are small but have many rooms, occupied by editors, publicists, cover designers, social media managers, web designers, financial managers and administrators, either working in-house or invited in as contractors. Their authors live outside these houses, dependent on acceptance to raise their book-child before launching it full-grown into the world.

But there is another type of independent publisher in Aotearoa – the single parent who lives without a house or, better imagined, moves from room to room, initiating and executing every aspect of book creation themselves. These houses are occupied by the independent author, raising their own children, sending them into the world and hoping readers will love them as much as they do.

Writers once had limited choices of publication pathways, which could be summarised broadly as submitting work to a publisher and awaiting acceptance, or paying an organisation like Xlibris to transform their manuscript into a book. The first pathway promised readers quality, the second drew suspicions of vainglorious aspirations of an individual who couldn’t make the cut.

There’s an individualistic edge to these voices, sometimes cynical, sometimes generous

The departure of international publishing presence in Aotearoa has increased the importance of small presses, but has also coincided with the advent of typesetting, printing and distribution services that enable writers to create their own books. A third pathway has opened.

I interviewed six of these author-publishers and asked them about their process and their situation in the literary ecosystem of Aotearoa. There’s an individualistic edge to these voices, sometimes cynical, sometimes generous. All highlight the need for collaboration in some form, just not at the price of the author compromising their product. Having published three of my own novels in the last few years, I could relate to their determination and their frustrations, and also their experiences of learning plenty from working through the process.

Are independent writers vainglorious? Possibly, but the same could be said of other writers. The following interviews suggest that their perseverance comes from deeper motivations fuelled by legitimate artistic forces. Above all, I want to present their voices and work on The Pantograph Punch to demonstrate that high quality writing can come from writers who have chosen this path.

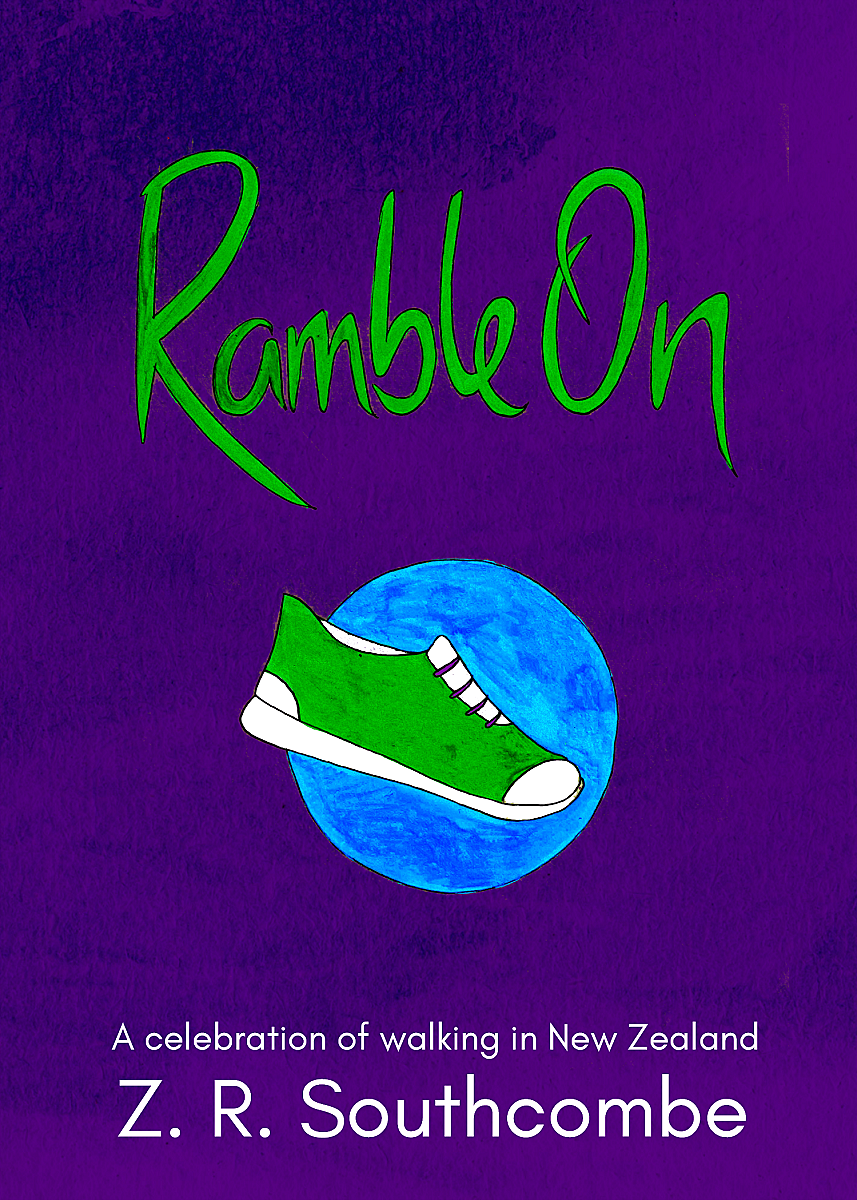

Z.R. Southcombe: Entrepreneurship of and for youth

I’ve read some of Zee Southcombe’s children’s book, The Caretaker of the Imagination. Accomplished and lyrically presented, it reads like poetry.

Until recently, Southcombe lived and created in Auckland, amongst authors connected to the New Zealand Book Festival and SONZA (Spotlight on New Zealand Arts). She shines online, not only as a writer and artist, but as an energetic blogger and social media presence.

She’s recently moved to Dunedin. I asked Southcombe if her reputation preceded her immersion in the city’s arts community. “I certainly wasn’t well known,” she says, “but I submitted some of my pieces to the inaugural Books As Art exhibition, and was labelled a ‘prominent artist’ by the Otago Daily Times, so something has worked!”

Something has indeed. Since launching her first book, What Stars Are Made Of, in 2014, Southcombe has been a finalist in the Sir Julius Vogel Awards, and expanded her portfolio enough to supplement an income working at the Otago University Book Shop. How does that work? Southcombe says,

I had a loan for my first print run, ran a small crowdfunding campaign for a children’s anthology, and am now blessed with sponsorship through Patreon. Multiple income streams suit my business: in addition to selling books, I teach creative writing and art, I create handmade journals, and I sell zines. I am now settling into a profitable model, but it took some hard lessons.

Southcombe is not the first writer to diversify in order to make a living, but she is another example of an independent artist with passion, drive, and willingness to explore alternative pathways to the traditional routes of reviewing, editing or writing for publications.

She’s had help along the way. “I was fortunate to know two lovely booksellers, Mary and Helen Wadsworth, who offered to launch my debut children’s book,” she says. “We made over one hundred sales on launch day, and it helped me gain confidence in selling my work. From there, I sold at markets and festivals, and online. I haven’t made the effort, yet, to approach bookshops. I enjoy being able to sell directly to my customers.”

This direct contact with readers, coupled with a desire to support other creatives, is another characteristic of independent writers in Aotearoa. Zee publishes under her imprint, Blue Mushroom Books, and offers “a space for people who don’t consider themselves writers, to have their voice heard.”

This extends to her young readership, many inspired by Southcombe’s school visits. Not one to wait until she’s joined a programme like New Zealand Book Council’s Writers in Schools, she has gone it alone in an effort to fulfil her primary mission to "re-inspire wonder and imagination in readers of all ages, and to remind children that no matter how much more ‘control’ adults have, children have so much to offer to us. My little voice helps encourage the literary voices of the next generation of writers."

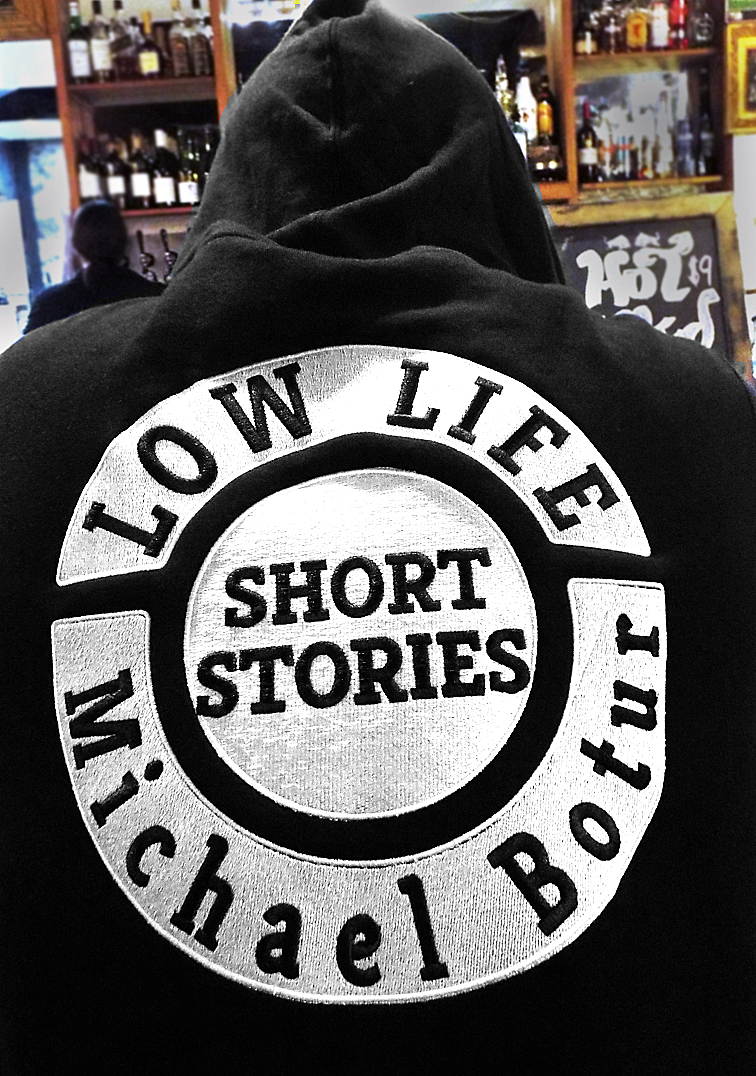

Michael Botur: The Northland maverick

I’ve recently read Moneyland, the debut novel by Whangarei writer, Michael Botur. It’s a thought-provoking dystopian work for young adults set in 2037. An Aotearoa version of The Hunger Games, Moneyland follows a competition for cash that turns deadly for its teenage participants.

Last year, Botur wrote a piece for The Spinoff relating his experience of crowdfunding support for his novel’s publication. I asked him if he’d ever sought funding through more traditional routes such as Creative New Zealand grants. He lamented, “Applying for grants has always been a flop, a total waste of time.”

Time is important to Botur. Even as he made the print version of his novel available for sale, he fast-tracked its delivery directly to his target audience. Moneyland has been read over 5000 times on the reading app, Wattpad. In the app’s simplified rating system, 200 readers have ‘voted’ to share their enjoyment of the story. These are alternative metrics of success, but ones any writer would be pleased to receive were they on Amazon. Wattpad has also garnered Botur a plethora of enthusiastic reviews. "The concept of this book is amazing!! I loved it!!” writes ‘Peacebunny101.’ “The characters are superb and the ending is so so so good!!"

Botur is representative of many independent authors actively rejecting reliance on the industry’s principal players, including literary journals

This year, Botur published Lowlife, his fourth collection of short stories. He places his writing in the “‘gritty realism’ genre…telling the stories of average Joes who get into conflicts just trying to keep their heads above water.”

Botur works as a full-time writer, earning money from blogs, columns, ghostwriting, interviews and newsletters. “I adore journalism,” he explained, “but I didn't hold onto the machine tightly enough and it threw me off.” His comment suggests rejection by the industry, but the relationship is reciprocal. Botur is representative of many independent authors actively rejecting reliance on the industry’s principal players, including literary journals. Again, his primary concern is time:

When a literary journal takes three to twelve months to respond to your piece of writing, they expect the following: They expect you to need their opinion on the work to decide if it's quality or not; they expect you not to develop the piece; they expect you not to publish the piece yourself, as if a blog somehow affects their sales; they expect you to give control to a publication which won't share your work with terribly many people.

Instead, in blog posts like “Artist, Help Yourself: Saying ‘No Más’ To Publishing Piranhas,” Botur admonishes writers to ignore the gatekeepers and release their work free to the world via digital media. His view extends to the mainstream review culture in Aotearoa:

Literary review publications can be jaw-droppingly snobby about self-published books. You can have amazing writing in obscure, unheard-of self-published books, and you can have shit writing in books put out by huge publishers. And it can be vice versa, too. Forming a publishing company doesn't make a piece of writing any better or worse.

Far from vanity, Botur is driven by this passion for reaching readers. “Independent publishing is publishing a piece of work because you respect it enough to know it needs to be shared with the world.”

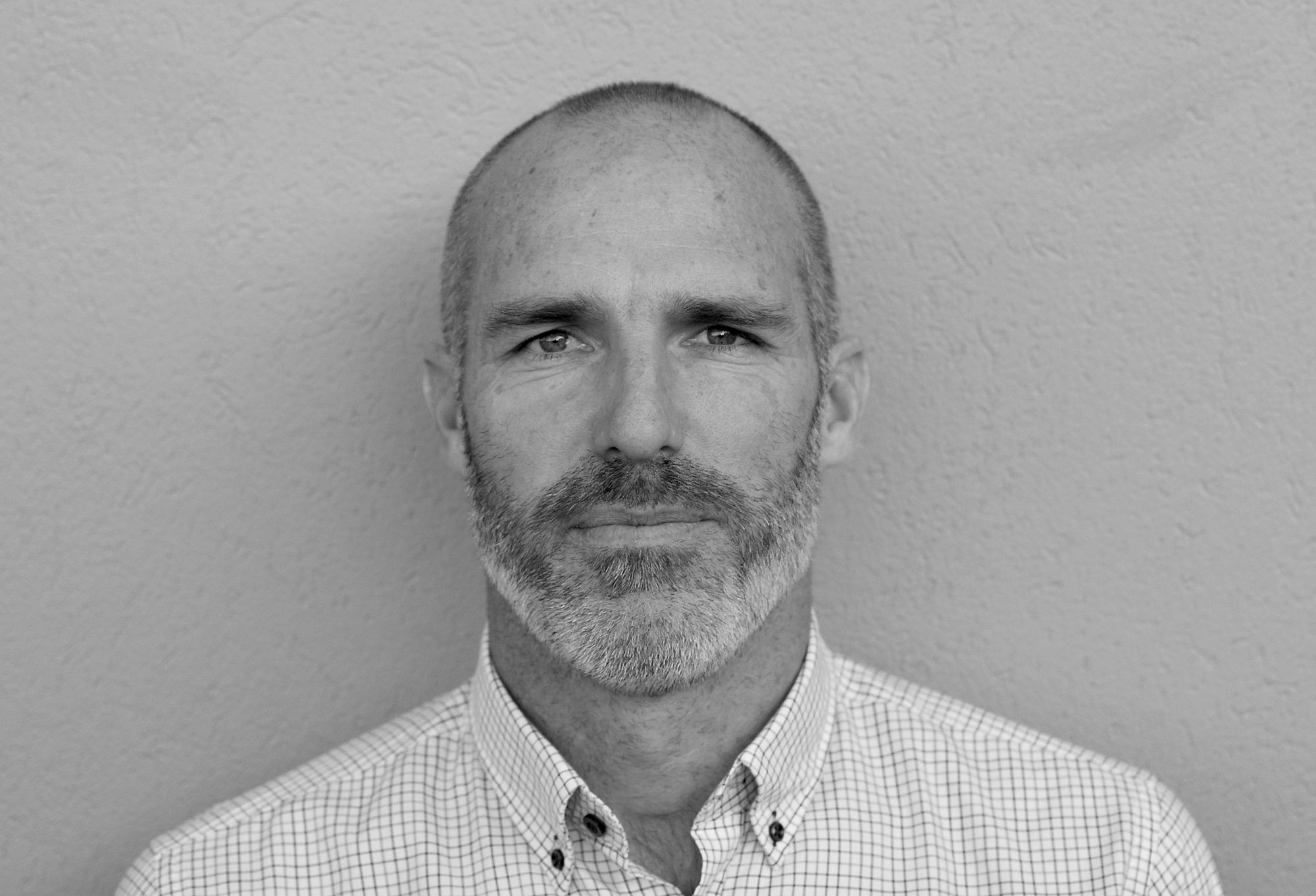

James Russell: Winning over kids and Whitcoulls

I’ve reviewed both books in The Dragon Defenders series by Auckland children’s writer, James Russell. They’re fun adventure fare about brothers Flynn and Paddy who live on ‘The Island,’ the home they share with their parents, sister, horse, dog and about 100 dragons. The novels are aimed at pre-teen readers who like dragons, maps, bullying bad guys, survival tactics and themes of victory through cooperation.

You may know this series. Last year, Russell managed to crack Whitcoull’s list of Top 50 books for children, one of just two Aotearoa novelists to do so, and the only independent of the two.

I realised early on that if I was in, I was all-in

The self-publishing community envies Russell’s success. When I met him at the 2014 New Zealand Independent Book Festival, he was just starting out. Soon after, he ended his full-time job as editor of The New Zealand Herald’s Element magazine and tackled full-time writing. He says,

I realised early on that if I was in, I was all-in. I couldn't do a half-arsed job of it. I worked really hard to get the highest standard of everything I could. I got the best illustrators I could find, and we worked collaboratively together. The books had to look amazing, to feel great in your hand.”

But how did Russell manage to achieve nationwide distribution in a few short years? Timing played an important part, as Russell acknowledges when he says, “There really weren't that many people self-publishing when I started in 2012.” But so did clever marketing strategies like hiding dragon eggs around the city for folks to find in exchange for free books. But then he hit on a technological game-changer. “The development of augmented reality (AR) content for my books has proven to be great for attracting attention.”

The integration of his books’ content with a free app allows readers to see maps spring to life in 3D, or video clips of the book’s villain (played by Russell himself). The enhancement landed him a breakfast television spot and has continued to pay dividends. It has also seen him recognised by the mainstream book industry. Russell states, “At the recent Auckland Writers Festival that map was blown up to the size of a billboard and stuck to the concrete, so users could stand above it and watch the dragons flying around the hills and listen to the tuis singing in the forest.”

Russell’s desire to write and publish is driven by noble intent:

I'm really passionate about kids reading. As a boy I loved the action-packed nature of The Famous Five and the Willard Price novels. I've learned through my own children and their friends that many kids who say they don't like reading just haven't found the right book. And that's often one that makes your heart race – that's what I aim for in my novels.

Ultimately, he sees it as being about reaching readers and relying on their response to gauge his success. “I really don't think the reading public takes that much notice of the publisher's mark on the spine. They just want a good book. Bad books will die, good ones will live…It's an emotional rollercoaster. Sheer bloody-mindedness helps!”

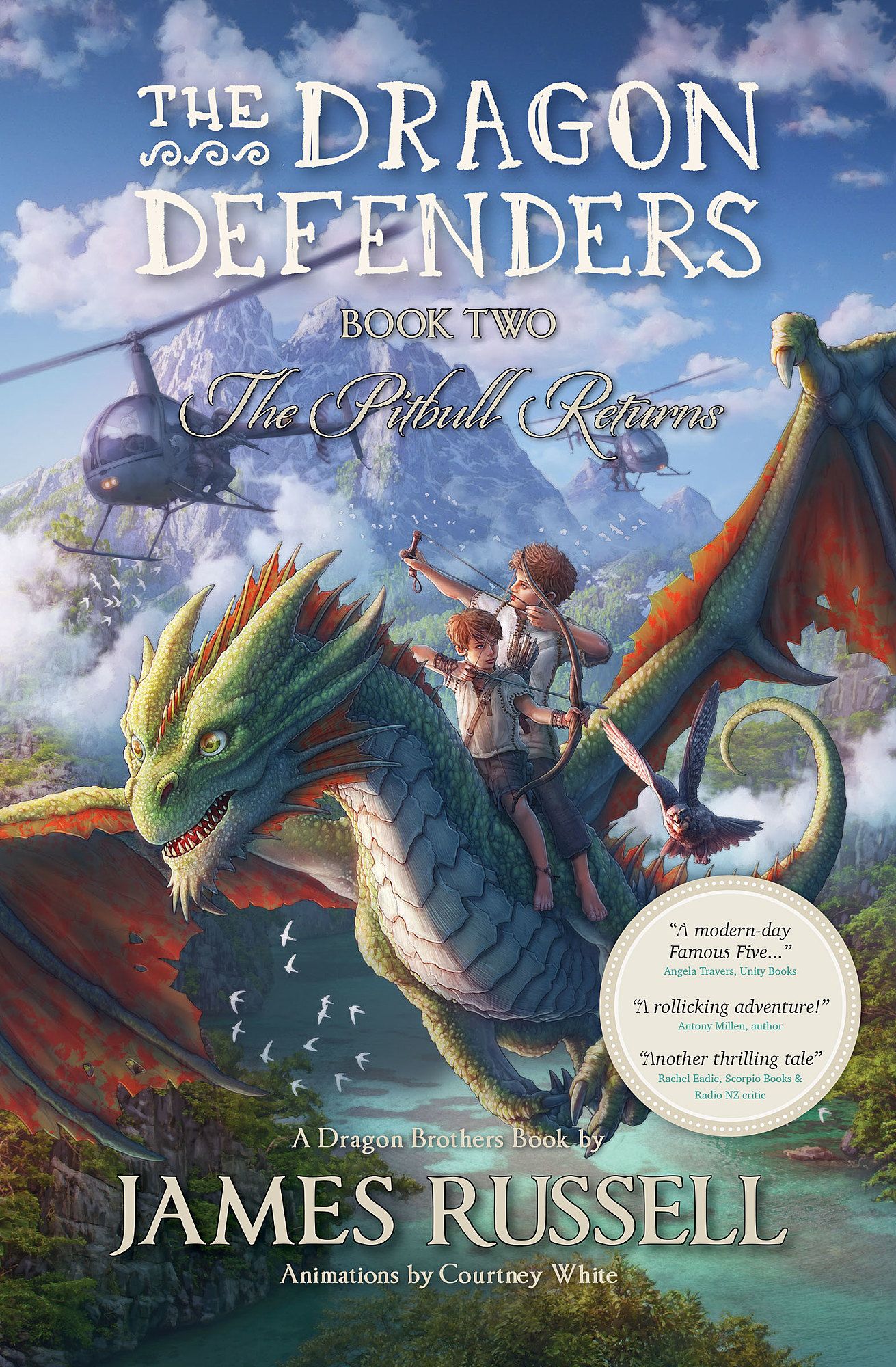

Nix Whittaker: An algae and she knows it

I’ve reviewed Nix Whittaker’s novel, Hero is a Man. It’s an impressive debut in terms of world-building, character relationships, and her very clever speculative premises.

Since launching her book in 2015, this Taumarunui teacher has published six more novels and a collection of short stories, with two further novels due out this year. That’s ten books in three years. How does she do it? “Work!”

Whittaker is driven by a desire to improve every aspect of the process, a trait that often distinguishes the independent author

Whittaker is driven by a desire to improve every aspect of the process, a trait that often distinguishes the independent author. “I meet so many people online who are starting out who say, ‘I’m bad with technology’ and they aren’t willing to learn anything new. To be an indie you learn it all, even the stuff you hire out. Indies learn their trade so they don’t get ripped off.”

Whittaker does everything herself except line editing, but she’s taking an editing course to increase her ability and independence. This isn’t to say she eschews collaboration. Originally, Whittaker joined the New Zealand Society of Authors but felt underserved. “The only things really available for indie authors were slightly cheaper manuscript reviews and a discount on editors’ services. There is no real engagement.”

Instead, Whittaker found her tribe with SpecFicNZ as a writer of sci-fi and steampunk romance. “Their fees are a fraction of what NZSA asks and they love indie authors. I managed to get a grant and a heck of a lot more engagement. I think people need to make their own tribe of writers.”

Putting her time where her mouth is, Whittaker has launched a website showcasing Aotearoa authors. “I was shocked to see so few profiles on the New Zealand Book Council’s site. I don’t have some imaginary bar that people have to cross. You have a book, I will list it.” Whittaker’s site already features over 350 New Zealand writers, including best-selling authors such as Tracey Alvarez, Steffanie Holmes, and Emily Larkin, who are not featured in the 700 profiles showcased by the New Zealand Book Council.

This seems a logical extension of Whittaker’s digital platform, especially considering her location. Taumarunui’s remoteness influences her approach to distribution; Whittaker doesn’t bother with brick-and-mortar stores, instead focusing on Amazon. She says,

I sell mass market stuff and people read heaps of those and need a cheaper way than the exorbitant prices of paperbacks in New Zealand. No one would pay full price for my books here in New Zealand because to brave a new author I’d have to be in the bargain bin and the only way I’d be there is if I was published by a big-name organisation.

Nix Whittaker’s self-appraisal is refreshing. “I’m barely a blip in the New Zealand literature scene. As some writing groups would describe me, I’m algae – and I know it. I’m not sure how to be plankton yet, but I’m learning and I’m happy to use this time as experience.”

Christodoulos Moisa: An old hand on a new plough

I’ve reviewed the first two instalments of Christodoulos Moisa’s Wolf trilogy for Crime Watch. They’re good, modern examples of crime fiction with literary and historical merit.

Kevin Ireland agrees. He declared Moisa’s debut novel, The Hour of the Grey Wolf, “a real achievement – and a remarkable work in broadening the range and the depth of inquiry of the New Zealand novel.”

I caught up with Moisa in Whanganui recently while moderating an event organised by the Ngaio Marsh Book Awards. I learned of Moisa’s decades of literary experience. In 1981, he won the National Poetry Prize and in 1983 was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council Fellowship. He is well respected in Whanganui as an artist, photographer, poet, teacher, reviewer and novelist. “I enjoy Whanganui,” Moisa says, “it’s a good place to write.”

While Moisa’s recent foray into crime fiction is novel to him, his work as an independent publisher is anything but. Nowadays he produces his books the way we all do: digitally with the help of a printing service. A little different from his pre-digital days. He says,

When I first started One Eyed Press, I printed the books on cardboard plates. One compliment from a bookshop owner in Auckland was that the woodcut on the cover was superb. It was actually done in pen and ink but designed to look like a woodcut. Typesetting was usually done on IBM printers.

Moisa has embraced other modern aspects of the industry and is active on social media. But he cites reviews as his preferred publicity strategy, despite his frustrations in pursuing these. “I usually send books to magazines and newspapers with varying success for reviews. They usually do not publish reviews on indie books. The Book Sellers Association, The Publishers’ Association, and the Book Council lock indie publishers out.” He’s met similar road blocks with distribution. “I must have written to six or seven distributors. Only one offered to sell the book.”

My work draws on my own experience as an immigrant, as a Cypriot, as a teacher

Moisa began his new publishing era after retiring from teaching, supported by crowdfunding and a financial gift from a friend. “Many New Zealand authors have their first book financed by themselves, their partners or their parents. There is no shame in that especially as nowadays you have to spend $10,000 doing a creative writing course to be published by the universities which, if you push the envelope of the definition, is a form of vanity press.”

Moisa’s work is rich with content and themes that are dear to him and have much to say about modern times. “My work draws on my own experience as an immigrant, as a Cypriot, as a teacher, and as an activist against lead pollution and inner-city motorways. I have things to say about revolutions, civil war, terrorism. My work can be classified as reflective to some degree, especially the poetry.”

Isa Pearl Ritchie: Feeding fiction with a PhD

I’m currently reading Isa Pearl Ritchie’s second novel, Fishing for Māui, newly launched at Unity Books in Wellington. So far, I’m impressed by the novel’s multiple narratives, a similar technique to Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible. Ritchie’s story promises to delve deeper into these characters and their relationships, in terms of whānau and mental illness with food as a unifying trope.

Last year, Ritchie graduated with a PhD in Philosophy from Waikato University. She titled her thesis, Shared Lunch: An Ethnography of Food Sovereignty in Whaingaroa and Beyond. I asked if her research feeds her fiction, and she seemed to appreciate the pun. She says,

It was actually my masters research that fed into Fishing for Māui quite a lot – I was looking at different discourses on food and nutrition so the food themes in the novel are building on that in-depth knowledge and understanding. I'm currently writing a novel that does draw on my PhD research though.

Ritchie says the process of publishing her own fiction was a steep learning curve. “Each part has required a lot of creative thinking and analysis,” she says. “Like walking in the dark where everything starts off being very unclear, I've figured a lot out as I go along and learnt what works or does not work.”

Despite feedback from publishers – “that my writing is good but not quite what they are looking for” – she speaks generously about the industry, recognising there are many factors at play. “Publishers take a big risk in every title they take on. Producing books is very expensive.”

Ritchie knows this from experience. She has invested more to ensure the highest quality of her second novel.

"It took me a long time working with a very talented designer, Katrina Berry from Floresta Design, to get the cover for Fishing for Māui looking really good. I realise that the chance of being really happy with it if a publisher had done that work is very unlikely because I have a very particular aesthetic." That said, there are times when independence is aided by collaboration. “It’s quite hard to market myself,” Ritchie says. She contracted professional publicity, which helped her secure a professional distributor.

For Ritchie, independent publishing has satisfied more intrinsic needs

For Ritchie, independent publishing has satisfied more intrinsic needs. “I have an opportunity to use a Creative Commons license which is in line with my values, and it also means that I can retain a lot of autonomy over my work, which is important to me.” Ritchie cites impressive precedents for writers like ourselves. She states,

Publishing has long been challenging if you're doing something a bit different, which is probably why Virginia Woolf's brother paid for the publication of her first two novels before her husband's publishing business took off, and why Poe and Proust originally had to pay for their work to be published.

Ritchie sums up her attitude towards her work, her readers, and her industry beautifully. “I think the most important thing is to show up and to project confidence and commitment to my work, because that is what people will respond to.”*

In this new age of multiple publication pathways, readers are now swamped with selection. It is difficult for writers to build their house in this swampy paddock, and to build it high enough to be seen. Independent authors know it takes work to reach readers. To do this, they produce the best work they can, and they spend countless hours writing for free, marketing, pitching ideas and collaborating with others. But they want a level paddock in which larger houses don’t hold all the locks and keys.

No one owes us anything, least of all the readers of Aotearoa. Still, there are some agencies, like those mentioned in these interviews, that an independent writer should be able to rely upon. These entities exist because of author-paid fees or taxpayers. Of course, decisions need to be made, but when agencies select an author to support, they not only enable the author to accomplish something, they also signal to potential readers that this author’s work is worth something. And independent authors are still seen as less worthy than authors published by mainstream publishers. Where is the line where this becomes snobbish?

Independent authors ... want a level paddock in which larger houses don’t hold all the locks and keys

This year, my own profile was added to the New Zealand Book Council’s Writers Files. I’m very pleased to be one of just ten profiles added annually. Since 2013, I’ve emailed applications bolstered with new writing accomplishments. In my first application, I had one book to my name and a blog. By the fourth, and successful application, I had three novels, over 100 blog posts, several short story awards, publications in literary journals, a book festival appearance and a small residency.

I only have a vague notion about why I was selected. The only criteria I’ve seen are listed in the categories on the application form: published books, other significant non-book publications and awards. I suspect part of it, however, is that I write about Aotearoa and I engage in the conversation about literature in Aotearoa in recognised journals like The Pantograph Punch. A similar process is used for our major book awards. Although undoubtably an excellent book, by declaring Pip Adam’s The New Animals, the best fiction book of 2018, the Ockham judges are really declaring it the best book they read of a selection of books entered by those who knew how to enter the award, or cared about the outcome.

I would suggest that readers are underserved if they are not at least made aware that independent authors are out there. As a reader, don’t underserve yourself by passing over a book because the author is independent. Many of them are creating terrific stuff.

Interested in more independent Aotearoa voices? I recommend you check out Tui Allen (Russell), Louise de Varga (Auckland), Vicky Adin (Auckland), Bronwyn Elsmore (Auckland), Kirsten McKenzie (Auckland), Lizzi Tremayne (Waihi), Nikki Crutchley (Hamilton), Chris Eyes (Taupo), A. D. Thomas (Taumarunui), Pixi Robertson (Taumarunui), Tony Chapelle (Palmerston North), Carole Brungar (Levin), and p.d.r. Lindsay (Southland).

Feature image by Dean Hochman (CC BY 2.0).