Aural Fixation: In Praise of Radio Plays

The radio play is an unfairly neglected and under-appreciated artform; now is the time for its revival, argues Nathan Joe.

The most infamous myth in the history of radio plays is that when Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds was first broadcast in 1938, it caused nationwide panic in the United States, convincing unsuspecting listeners that their beloved planet Earth was under attack from Martians. While the story of this hysteria has since been disproved, it's a legacy and myth that persists because, at one time, people held the medium in a kind of reverence and high regard. It’s the sort of infamous hype that precedes a work itself, not unlike the riots caused by the premiere of the ballet The Rite Of Spring in 1913. Yes, there’s nothing theatregoers love more than a big scandal. Nowadays, however, the notion that a play, let alone a radio play, could cause such a heated national response seems laughable at best.

As American critic Elissa S. Guralnick aptly puts it in Sight Unseen, her scholarly overview of contemporary radio plays: “The distinguishing feature of plays conceived for radio, that we do not see them, is true not only literally, but also metaphorically.”

There is probably no other artform as neglected, by scholars, critics, makers and consumers alike.

Indeed, the radio play is a long-forgotten artefact, and unfairly maligned as such. There is probably no other artform as neglected, by scholars, critics, makers and consumers alike. Worse even than museum pieces, radio plays are often inaccessibly archived by larger broadcasting organisations (BBC, RNZ), due to licensing agreements that permit them to be available only for a limited time. To find them, then, means excavating the strange pockets of the internet (YouTube, archive.org) where they have been uploaded illegally and are destined to live in obscurity.

Video may have killed the radio star, but if there were any time for a revival of radio plays, it would be now. In an age where lockdown is still fresh in our cultural consciousness – and for many places around the world, still happening – the radio play offers our bloodshot eyes a soothing rest from oversaturated screens. While most artists and theatre companies find themselves scrambling to produce and release content in the livestream format, this oft-neglected medium of radio strikes me as the perfect panacea. Indeed, if radio plays originally seemed destined to be forgotten in the annals of broadcasting history, one silver lining of Covid-19 has been a reassessment and adaptation of the arts, particularly with theatre-makers reconsidering what tools they have at their disposal.

For many unaware, Aotearoa New Zealand’s very own publicly funded radio broadcaster RNZ has made an active effort to record contemporary radio plays over the last few years. Over at RNZ’s Major Plays collection you can find exactly 26 different radio plays neatly archived. It’s a humble glimpse of our contemporary theatre culture, but it’s also an eclectic snapshot of our finest theatrical voices. Some of the country’s most established and well-regarded playwrights can be found there, including Roger Hall and the late Dean Parker. But lest radio plays be seen as simply a platform immortalising straight white men and reflecting nothing but the pre-established canon, the talents of our next generation of playwrights are there too, with the likes of Sam Brooks and Jess Sayer thrown into the mix, as well as less conventional plays such as Hayley Sproull’s bicultural monologue Vanilla Miraka and Grace Taylor’s poetic ode to Auckland My Own Darling. I hasten to add that Brooks and Sayer have never had the pleasure of being programmed by a mainstage theatre company, despite their numerous successes and accolades, but in this modest collection, they’ve been given the same cultural capital as their predecessors, sitting comfortably alongside them.

Having never caught Jess Sayer’s road-trip three-hander Wings in its original live form, I was pleased to remedy that cultural blindspot. In radio form, it remains an effective familial chamber drama set inside a car, moving with the velocity of a vehicle barreling down the highway. Sisterhood has never seemed so scary.

The chance to revisit Sam Brooks’ Wine Lips also illuminated new depths in the text. The adage that a film stays the same while the person watching it changes is a sentiment that audiences don’t often get to experience with theatre. Radio offers that chance, that glimpse. Wine Lips, in particular, proved to be more affecting the second time around, my own experiences (and age) now hewing far closer to the characters than when I originally saw it in The Basement’s Green Room. Brooks’ play proves to be as much of a moving testament to the struggling artist in the big city as ever. It’s hard not to imagine it as a perfect time capsule of 2010s millennial angst and the quarter-life crisis.

Radio isn’t simply a cheap alternative, but a medium with its own unique merits.

Adam Macaulay, Commissioning Editor for Drama at RNZ and producer of many of these radio dramas as part of his Live on Stage. Now! initiative, is an unsung hero and champion of this medium, taking successful productions at BATS and repurposing them for radio. This doesn’t always result in a perfect alchemy, as these plays were not necessarily intended for radio when written, but fill an often overlooked gap in the ecology, so to speak.

In listening to these plays, I feel a deep blush of nostalgia and fondness for the form re-emerge. As much as I love the experience of gathering, the essential component that makes live performance so riveting, this recent lockdown has reminded me of my introverted nature, tapping into a desire for less of the busy and chaotic assault of metropolitan life. Radio offers the pleasures of the text without the hassle of theatre foyer anxiety.

While many countries are still adapting to the simultaneous compromises and innovations that social distancing demands from theatre, we in Aotearoa are eager to move on and return to the inimitable intimacies of the live experience. With lockdown behind us, the popularity of the live-streamed events seems to be fading alongside it. As Playmarket script coordinator and playwright Stuart Hoar points out, “the filmed theatrical experience is not quite theatre nor is it a film.” It’s a half-breathing simulacrum of the live experience, something watched with the proviso of “I can imagine it would be much better live.” What radio offers, by comparison, isn’t simply a cheap alternative, but a medium with its own unique merits.

It’s strange to consider the many reasons radio drama has never really picked up as a modern form of entertainment, especially in the age of podcasts and audio books, which strike me as a perfect platform to deliver it on. Sadly, radio drama remains stigmatised by its association with the likes of the BBC’s radio soap opera The Archers. In reality, some of the greatest and most talented playwrights of the theatre world have dabbled in the form, well beyond simply establishing themselves. It’s where British writers like Caryl Churchill, Harold Pinter, Tom Stoppard and Howard Barker challenged themselves and their audiences for decades.

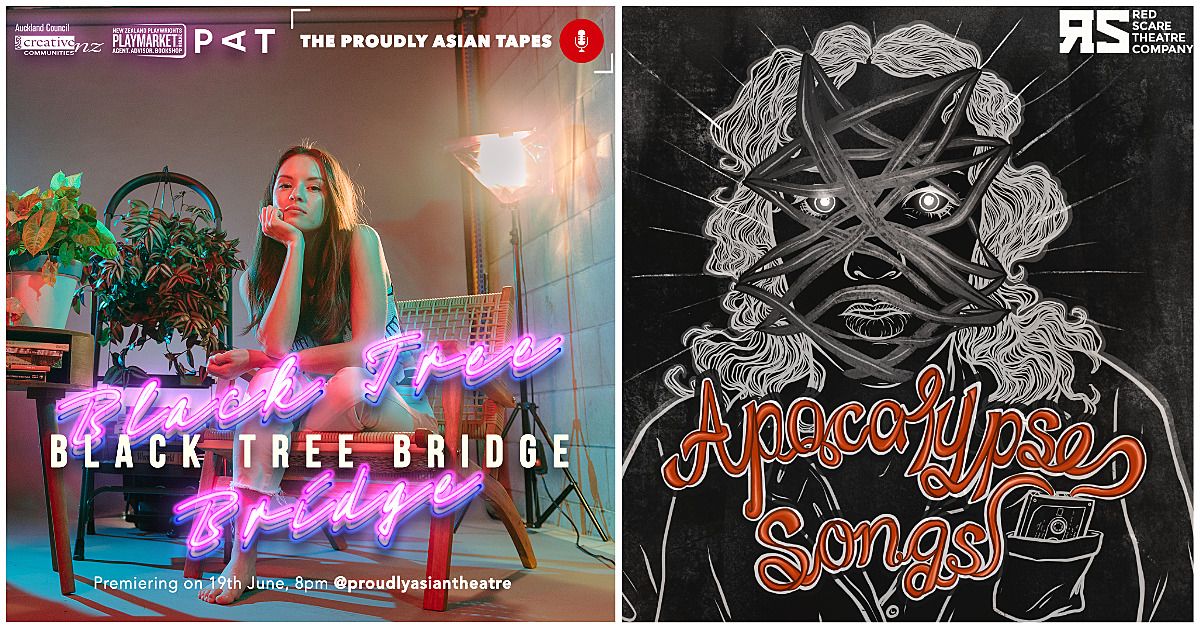

Black Tree Bridge and Apocalypse Songs

Emerging from the dust of the pandemic, local playwrights and artistic directors Cassandra Tse (Red Scare Theatre) and Chye-Ling Huang (Proudly Asian Theatre) have embarked on their own journey into the radio drama medium. It’s a choice made as a response to the conditions and constraints that the current pandemic crisis imposes. Both see radio plays as not just a quick-fix compromise or a cheap and lazy alternative, but an opportunity, embracing both the limitations and liberations that come with the medium.

It’s hard not to notice that these two makers are also young women of colour, the diametric opposite of what could be seen as the old, white, male gatekeepers that might be associated with the medium. Perhaps it should be no surprise that in 2020 the legacy of Orson Welles may soon be displaced in the cultural consciousness by young women of colour as the new faces of radio drama, paving the way for our country’s most vibrant contemporary theatre.

In Black Tree Bridge, Huang offers a text steeped in poetic imagery and elaborate stage directions. I remember attending an early development reading for the play where questions arose multiple times at the Q&A that challenged the practicality of staging such a play. Her latest draft was intended for a public live reading but was cancelled as concern around Covid-19 grew. Though Huang’s play was not originally intended for radio, this solution born from necessity has quickly proved itself to be a surprisingly successful alternative, displaying qualities the live reading would have failed to offer. Decorative stage directions, the bane of play readings, are read by a designated actor in the radio version, turning them into what might as well be called poetry. Music has proved to be a larger component here, too, with sound designer and musician Nikita Tu-Bryant recruited to add additional layers of aural texture.

Cassandra Tse in action. Photo courtesy of Red Scare Theatre Company.

In a section where Chrys, the Chinese-Pākehā protagonist, is visited by a story of her ancestors, Huang’s imagery and ability to time-travel the audience is created simply through the elegance of the prose and musical accompaniment. It’s a piece of writing that decorates the imagination but might prove difficult to envision on stage.

The soil that grew him was spilt with blood, lies and crushed with boots from foreign lands. His last refuge called to him. He went to the bridge where the black roots of the tree beside intertwined, blossoming yellow leaves that fluttered like confetti into the unfathomable depths of the green river below.

It’s one of the great ironies that our ears can paint a much more vivid picture of moments like these than our eyes can. The sound of water conjures up the sea with far smoother suspension of disbelief than even the most talented physical theatre-makers could elicit with the finest materials. Radio need not apologise for its limitations of budget or the absence of visual signifiers. The mind’s eye can be as visually extravagant as it wants to be, a complicit co-author to the playwright. Radio has always been, even more than the stage, a writer’s medium.

While Tse’s Apocalypse Songs was originally written in 2018, production didn’t begin until Aotearoa entered lockdown. It’s a project that struck her as perfectly suited to the conditions we were currently living in, as it could be recorded under Level 4 and provide entertainment for audiences all over the country in the safety of their own homes. The subject matter of the piece, too, is a tribute to the format, centered around arts journalist Amy Louise Chen, who hosts a fictional radio show that explores obscure New Zealand music history.

It’s the intimacy of the format that Tse seems most obsessed with, detailing:

[CLARA] whimpers softly. Perhaps she is crying – the quality of the recording means we can’t quite tell. She calms herself down and says:

CLARA: This room is dusty. It’s growing.

CLARA shuts off the recorder.

Back to the interview. JOYCE exhales.

A whimper. A sob. The quality of a recording. An exhalation. Relatively minor gestures or details that might disappear on stage are zoomed up in extreme detail. And, whereas the stage playwright might leave these gestures for the director and actors to consider, the radio playwright treats these moments as if as important as dialogue itself.

Another significant advantage of the medium for Tse has been the freedom of a larger cast of actors than is typically allowed or recommended for independent theatre, particularly for characters with minimal dialogue. Released as a four-part series, it also offers the opportunity to play with serialised storytelling that in a way that live theatre is traditionally unable to do. By releasing her episodes weekly, Tse wants to encourage the same hype for her listeners that surrounds a favourite television show.

When we return to the comfort of our theatre seats, I hope radio plays won’t be quickly forgotten again as simply a retro throwback

While both writers acknowledge the challenges of making a profit from radio-based work, especially when released online, they have both received degrees of support from arts organisations (including CNZ and Playmarket). And, despite the limited profit margin for radio work made independently, the potential for audience reach is far greater than in live theatre. Profit isn’t their endgame – accessibility is. Gone are the limitations of 65-to-100-seat theatres or a two-week season. Your audience capacity is essentially unlimited when they can sit in the comfort of their home or even lie in bed. On a purely logistical and practical level, there is no reason the reach of the radio play couldn’t be greater than that of its stage counterpart. In fact, it should be.

When normality returns to our theatre industry, I hope theatre-makers find themselves opened up to the pleasures of radio plays, propositioned with possibilities for endless aural pleasure. While nothing can hope to replicate or replace the live theatre experience, the radio medium offers an alternative full of endless possibilities. It’s not a case of one replacing the other, but simply having both on offer. For theatre-makers, the demand to be open and innovative is more urgent than ever with the threat of dwindling audiences and the precarious stability of venues looming over an entire industry. The current climate provides a fertile landscape for a paradigm shift and reconsideration of an artform, and we shouldn’t let this potential for a radio play renaissance pass us by. When we return to the comfort of our theatre seats, I hope radio plays won’t be quickly forgotten again as simply a retro throwback, but remembered as a stable silver lining amidst these dark times.

Black Tree Bridgeis currently available on YouTube.

Episode 1 of Apocalypse Songs premiered on 4 July, available on Spotify or Anchor.Fm, and episode 2 premieres on 11 July.

Feature photo by Will Francis on Unsplash