In conversation: Phil Dadson of From Scratch and Immi Paterson-Harkness

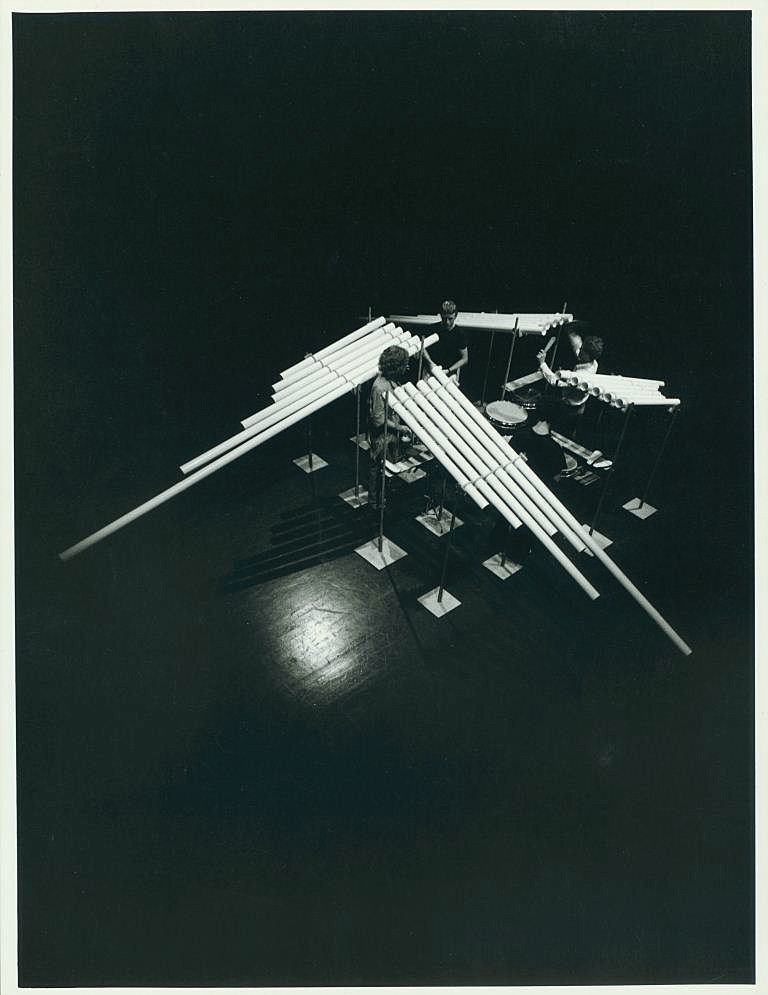

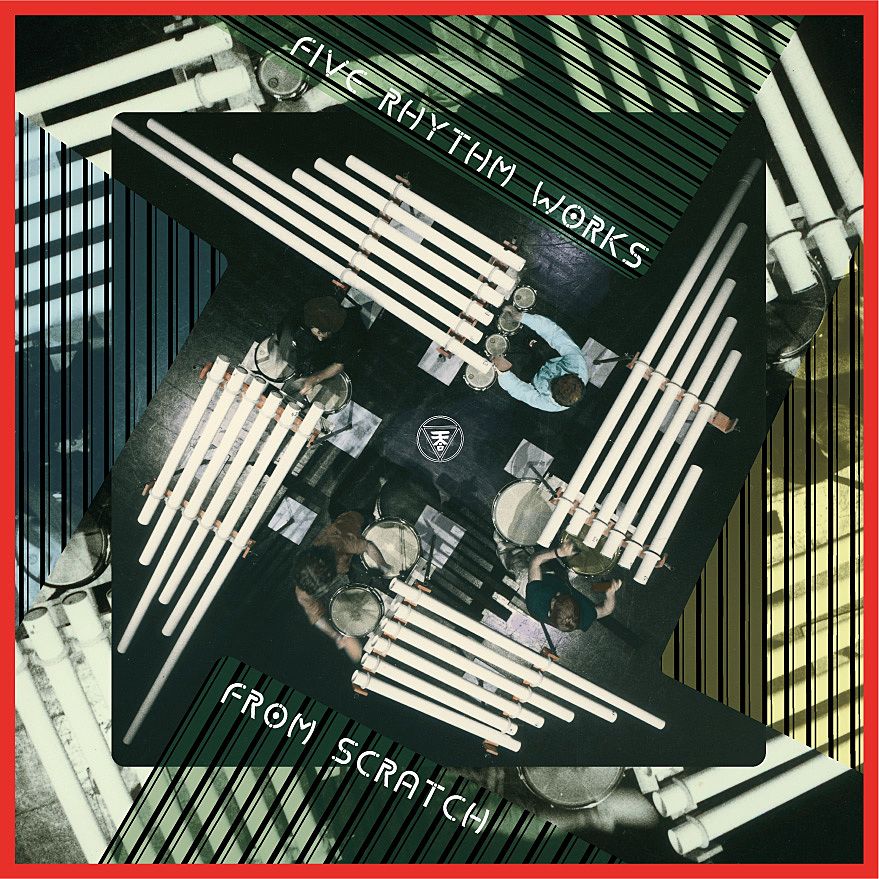

When you think of From Scratch you can't help but conjure up the image of men enthusiastically whacking racks of PVC pipes with what look remarkably like jandals. This might have actually been what they were doing, but hey, they did it really well. Between 1972 and 2002 they produced 11 recordings and three films, all while playing extensively at festivals throughout Asia, Australasia, the Pacific and Europe. They might not have topped any charts or written the song you'll hear down the phone-line when you ring the IRD, but this bears no relation to the massive success they had during their time.

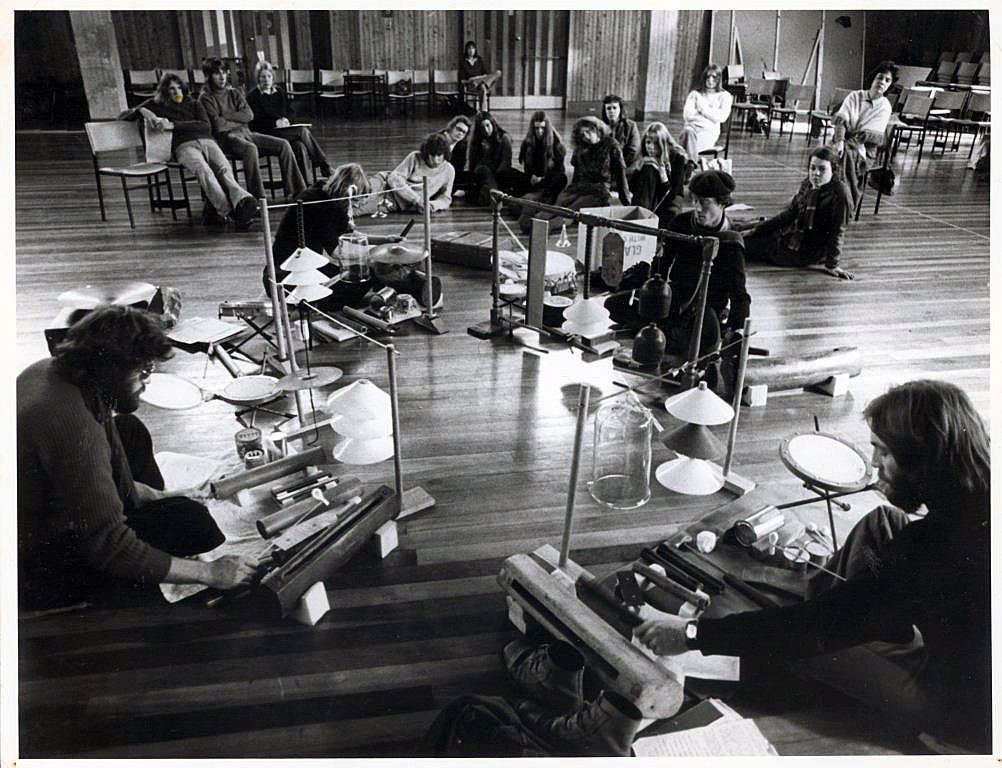

The group was formed by Phil Dadson. It's not often a documentary’s made about someone who’s still alive, but Dadson has managed it (if you've flown internationally recently you might have watched Sonics From Scratch). In the late 1960s, Dadson was involved in The Scratch Orchestra, a London-based musical group that took a non-hierarchical stance to performance (no lead violinist, thank you very much). As the name suggests, they also created instruments "from scratch". When Dadson returned to New Zealand he created a New Zealand offshoot - The New Zealand Scratch Orchestra, and a few years later formed a tighter, more cohesive group - From Scratch. The line-up changed many times over the next 30 years, the most famous probably Phil Dadson, Don McGlashan, Geoff Chapel and Wayne Laird.

It's hard to try and pigeon-hole From Scratch – they truly own their unique Pacific-styled sound. It’s mesmerising, hypnotic, tonally melodic, repetitive yet undeniably complex. There's also an honesty to the music. Each carefully thought out note is played in by hand (as opposed to a cold, mechanical loop). Really, it's a pity it's not what you hear when you're waiting for the IRD to pick up the damn phone.

I spoke to Phil Dadson over a pot of rooibos tea about Five Rhythm Works, the upcoming re-release of some of From Scratch's earliest works. The album’s being released by EM Records, an independent label from Osaka, Japan, run by Koki Emura.

Immi Paterson-Harkness: So let's start by getting down to the nitty gritty. Why percussion?

Phil Dadson: My background was piano. Piano is percussion, and I always loved the more rhythmic approach to piano playing. My first piano interests were probably boogie, blues and barrelhouse style piano. And then I got more interested in free-jazz style stuff. At that stage I was playing around with piano frames – you know, like dismantling pianos – and seeing what you could do with the prepared piano idea, but with an open piano frame.

I managed to find a straight stringed piano, which was amazing. There's not many straight strung, with no cross strings so everything is exposed. I had a beautiful little piano frame... I'd love to know where that ever got to. I welded a frame onto the back of it, so I could actually prop it. It was a heavy little devil to carry around with you.

Drumming is so primal and basic, I suppose. It was a natural attraction, in terms of “hit”.

There's a movement involved as well – a visual aspect. Was that part of it?

Definitely. It became a choreographic thing, particularly with polyrhythm. Because when you are playing the PVC pipes in particular – and that's very much a drumming technique, a kind of straight slap technique – you could visually sort out the different rhythms by watching the players. So there was the whole rhythmic choreography, in a sense, with how the rhythms were performed.

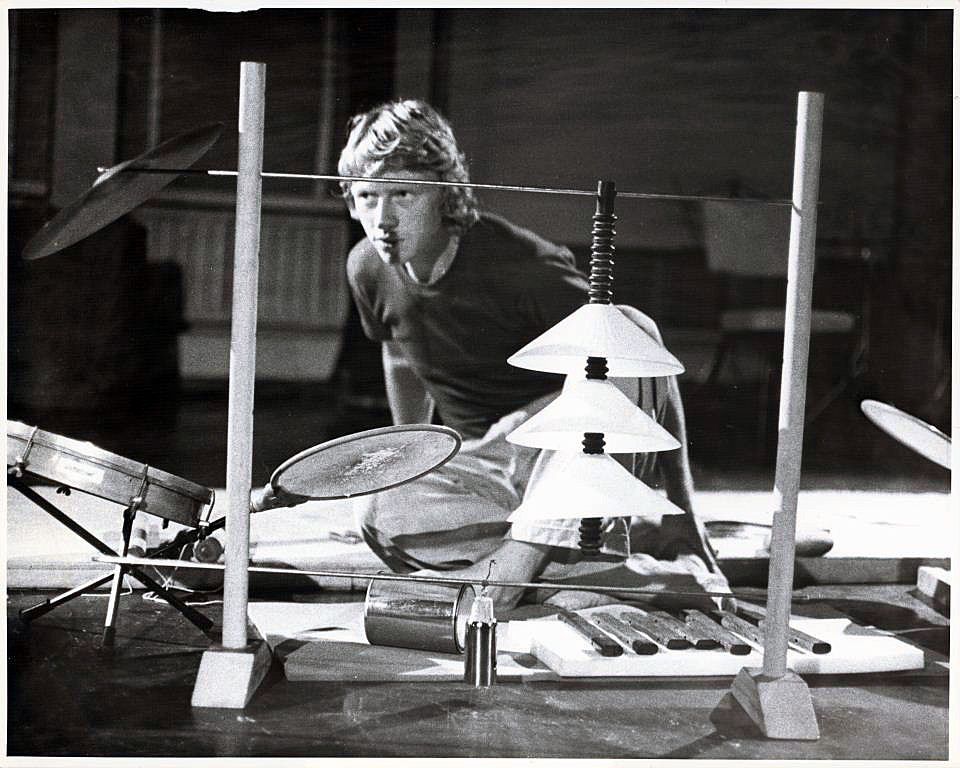

From Scratch included a lot of home-made instruments, and I know you also enjoy making sound from the things you find, like stones or household items. I'm interested in how you feel about conventional instruments, vs homemade instruments, vs found instruments.

I'm actually interested in the whole gamut of instrumental possibilities. I think the thing that attracted me to homemade and found, and the sourcing of that style of instrumentation, was the break from familiarity, and the potential for some magic with something that's fresh. It has also a sense of availability and accessibility, but a kind of mystery. Particularly when you hear it but you don't know where it's coming from. I love that kind of ambiguity, or mystery. But I'm not hard and fast about it – that it has to be built, or has to be found. Because I still play piano, and I think that one of my favourite instruments is actually double bass.

Do you have a favourite From Scratch traveling experience?

I guess a total standout would have to be Papua New Guinea. There are many, many places where I had an interest ahead in the traditional or classical music of the culture – like Japan, Thailand – and so going to the pacific has always been an inspiration and a reinforcement of some of the more rhythmic and process ideas that I'm interested in. Rather than trying to replicate things that are happening in those cultures, use them as a reinforcement for the approach. Particularly like using something like PVC pipes. So going to Papua New Guinea was just like going into a black hole – the completely unknown in terms of what the outcome might be.

It was just the most magical context to be in, because there were like fifty groups from all the outlying provinces of PNG that came into Port Moresby for the festival. And it was the early days of the South Pacific Arts Festival, so everything was pretty authentic. People came out of their villages, who had probably never been out of them before. It was an amazing privilege to be part of that, as a group of freckly whities. Talk about sticking out like a sore thumb!

I remember we had a performance scheduled in an outdoor venue that was basically a bulldozed semicircle in the outskirts of Port Moresby. It was pretty wild. There would be a village there, a school over here, and there would be this bulldozed space, and another one over there – kind of like paddocks. The group ahead of us was from East New Britain, doing ritualistic chant and dance stuff. And then we cart out our PVC pipes, do a quick setup, flail into something out of Gung Ho. And this is in the absolute heat of the noonday sun, broad brimmed hats on. It was so hot that all the pipes changed pitch, while the drums went flaccid. It went down okay with the locals. They just thought we were hilarious. They had uproars of laughter. So that was when I quickly devised tuning sleeves [for the PVC pipes], and that became a new development for the group.

Do you still use the PVC pipes at all?

I still love the sound of a good PVC pipe. For me it has a wonderful thump. It hums, you know? If you get a good set of them, they have a beautiful sound. A bit like bass guitar – it's got that slightly electronic tone. It's so different from bamboo. The bamboo has got the woody, ethnic association. That for me had all the kinds of associations I was trying to avoid, in terms of directly referencing Pacific sources. Bamboo pipes are used quite commonly in Fiji, and a lot of Melanesian places. And in Fiji they have the stamping tubes, basically hollow tubes with an exposed node at the base that is stamped on the ground to produce the resonant tone of the tube.

With stamping tubes, or PVC pipes for that matter, it will take quite a few people to make the whole tune? Is that the point?

Yes. Particularly with the struck pipes, with the slap tubes, to build up melodic patterning is something that evolved. Initially I didn't have a name for it. It was just a way of creating a pattern, and sharing the pattern between the players. Eventually I learned that it was called “hocketing”. Hocketing is a term that actually comes out of medieval music. It's where you split a rhythmic, melodic pattern between two or more players. Originally it was for singing, for sung patternings. There is some beautiful unaccompanied a cappella vocal music that uses this technique. It's medieval, but outside of Europe of course it's been used for thousands of years in other cultures. All throughout South East Asia hocketing was standard practice.

When you were performing the pieces, was there ever a time when you thought, “oh no, where am I up to?”

Oh shit yes. Half the performance skill is salvaging mistakes. It's a hell of a good training ground for that, brilliant for picking up on a mistake and using it, and actually getting out of it.

We had one very embarrassing incident at a World Drum Festival in Brisbane. From Scratch went over as a duo, and one [piece of music] involved a really tight, hocketed dualistic thing. We were wearing a set of PVC pipes on a body support, as well as vocalising and foot stamping. We fell out of time. We were cycling around the same patterns, trying to pick up the pattern without letting the audience know what was happening. For the thing to advance we had to get back into the phasing. And this was quite complex stuff, where you're dropping a beat, or you're adding a beat, going into cannon, then you're coming into unison. It was awful. You could just feel the heat, and the sweat, and the audience getting restless. Getting a few, “Oi! What's happening?”

It was an incredibly good learning curve, though. We realised you had to have the thing just so down, ahead of it. And be so relaxed. Relaxation is so essential.

Did you have a pre-show ritual to get you into the right frame of mind?

Yeah, I did, personally. I think most people did, actually. Certainly when the trio From Scratch, from the 80s, was at its peak and we were doing a lot of travel. Wayne, Don and I would do Tai Chi warm ups ahead of it, and have our own little cycle of things that we did, as a way of getting into the zone.

I like standing on my head, actually. That was always really good for me. I'd do the Tai Chi thing, but standing on my head just completely shifted me from the normal realm, of you know, being in the 3D world standing up that way. There's such a focus in it. You get there and you can't really think about much. You've got to be focused on coming out of that, and then go off and perform.

Two of the pieces in Five Rhythm Works are from the larger piece Gung Ho, that name referring to the Chinese socialist movement, meaning 'working together'. How does that concept work in terms of From Scratch's composition?

The aim was to build that egalitarian approach into the composing style. There would be changing roles, so everybody had to be able to do everything, in a sense. Initially that started out with having the three players on the low, medium/high rack, and the drone roll. And then the drone roll would turn into somebody going to play on the low rack, and the low would move into the highs, high would move into the drone. So you'd have that constant exchange. Anyone who might be seen to be leading something would actually be passing on that role. So there would never be anyone who stands out as a soloist or a leader. The collective was always the main focus.

It states in the liner notes that “after a break in London, Dadson returned with the realisation that anything, including art, could be music.” Can you explain this?

I don't remember ever saying that art was music. I mean, I do have a very expanded view of what can be music. But hey, you gotta draw a line somewhere. But you see drawing a line can be musical.

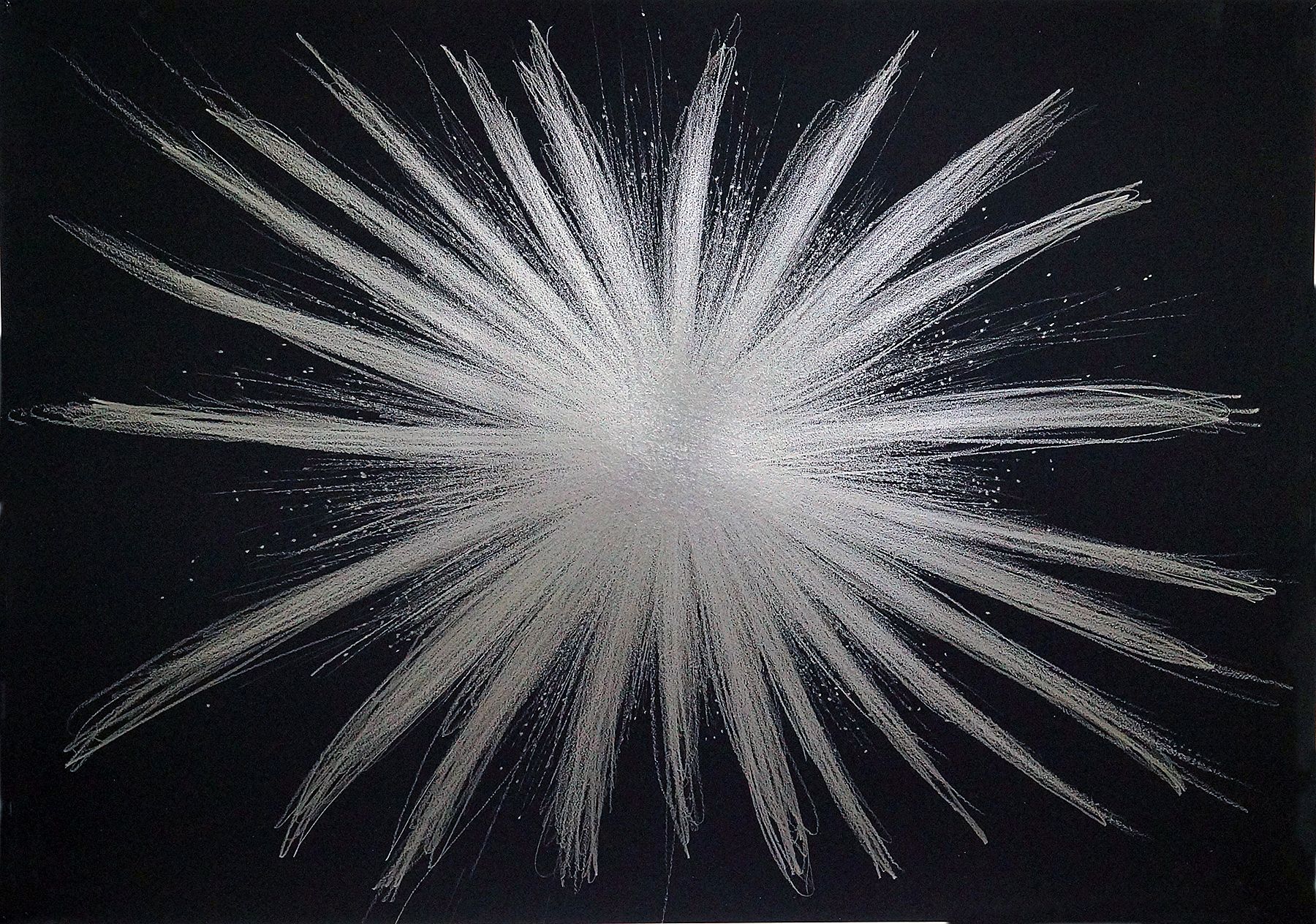

I'm pretty preoccupied with this idea of visual music. I'm in the middle of doing the March music series at the moment. A couple of years ago I started one in January – did a work a day through the month of January. Each one was a visual music chart, but it also had to work purely as visual, as well. They're like mute. They're images that you can, in a way, imagine the sonic realm to. I did the February one last year, and I'm doing the March one this year. I'm going to keep doing one each year.

What’s the aim of the music in terms of the listener's experience?

An aim, I suppose, would be to create a journey of sorts. An immersive and visceral experience. I love a sonic experience that actually takes you on a journey, that feels like it's not programmatic but has a structural shape that has shifts and changes that take you somewhere. And I like trying to put layers of meanings into things. Something that's accessible on the surface, but maybe you can interpret something else from it, something personal or something more philosophical. That's why that processed minimalist style evolved quite naturally.

And finally: what is the story with the label releasing the new album? Did Koki Emura approach you directly?

This totally came out of the blue. To be honest I don't know a hell of a lot about the background of the company, except that Koki Emura is passionate about music that is uncompromising and from the 70s and 80s era. He's dedicated himself to releasing music that is probably a little bit under the radar. Music that has been innovative within its own cultural context.

In a way, one of the works he selected, ‘Passage' – the very first recorded performance of the early From Scratch in fact – resonates with the gagaku music from Japan. Gagaku is the classical Japanese court music. It features the shō, which is the mouth organ. It's got a very specific reedy, ethereal sound to it. Beautiful music, I think. Quite drone oriented, but with percussive interjections through it. I've heard a couple of ensembles. One came through here, actually, must have been during the 80s I think. Of all places, it played in a dining room of one of the Grand Hotels, on the top of Symonds St.

And so you think that From Scratch's early work reminds him of this?

I think in that particular piece he would have felt a connection with it. Because of the reedy sound and also the slow rhythmic process kind of style. He obviously appreciates early minimalist stuff. The little sequel to this is that [the work] is also being produced in Taiwan as an LP, and then he's commissioning a Japanese group – I think maybe Goat, which is an experimental rock group – to do a remix project of the Gung Ho tracks. I've already sent all the charts for Gung Ho so they can study all the polyrhythmic stuff. It will be really interesting!

Five Rhythm Works will be released on Friday 6 May at the Audio Foundation, 8.30pm till late, as part of a SonicFromScratch event featuring a sequence of surprise visitors.