Imagined Art History: An Interview with Thomasin Sleigh

Holly Walker interviews Wellington-based writer Thomasin Sleigh about art, feminism, women’s creativity and motherhood in her second novel – Women in the Field, One and Two.

Art, feminism, women’s creativity and motherhood are in the foreground of Thomasin Sleigh’s second novel, Women in the Field, One and Two. Holly Walker picks up the conversation.

It’s an arresting title. Women in the Field, One and Two: it seems to hint at some sort of report on experience, a dispatch from the frontier. News from the field, for those of us stuck at home. Which field, though, and what are ‘One and Two’?

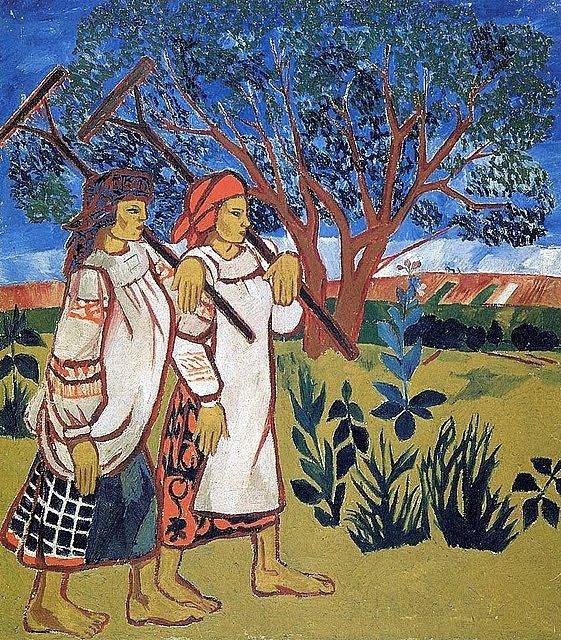

As it turns out, a pair of paintings. Of women. In fields. Striking, modernist paintings by the fictional Russian Painter Irina Durova, purchased for the fledgling New Zealand national collection in the 1950s on the advice of a fictional British expert, Ruth Bishops. Wildly incongruous paintings for New Zealand at the time, respectively painted and procured by women wildly incongruous in the art field. Irina and Ruth. One and two.

In fact, the novel is a kind of dispatch from a frontier: the past. It’s historical fiction, or as Sleigh herself puts it, an “imagined art history”. There really were British experts whose job it was, in the 50s, 60s and later, to advise a committee in New Zealand on which paintings to buy for the national collection. Such a role seems odd today. A ‘national collection’ suggests works by or about this place and its people, or at the very least, international works amassed here because in some way they illuminate our national preoccupations, but these purchasing advisors knew little about this country and some never visited. The works they recommended were selected to satisfy a colonial, Eurocentric ideal. Sleigh – an art historian by training who writes about visual culture in fiction as well as in reviews and essays – wondered what might have happened “if someone with a more radical, or just a bit more experimental taste had been in this role in the 50s”.

And so Ruth Bishops, having recently acquired the job advising on the New Zealand collection on top of her role as an assistant keeper at the Fisher Gallery, meets the much older painter Irina Durova at an exhibition opening, and later visits her at home to view her paintings. At first, Ruth is unimpressed, but on her second visit she is struck by two compelling and accomplished modernist paintings of Russian peasant women working in the fields. They seem to her important, exemplary post-impressionist works: a bargain for her New Zealand charges and their limited budget.

When Ruth’s work life at the gallery begins to unravel (and how could it not, for the sole female curator in an all-male, upper-class, patriarchal institution), Irina throws her a lifeline: an invitation to accompany her on a trip to New Zealand to transport and oversee the installation of the paintings in their new home. When they arrive – in a southerly gale – they find a conservative, repressed 1950s Wellington, less than receptive towards these ‘important’ works.

At first Women in the Field seems conservative, all buttoned-up cardigans and posh accents, but beneath the surface a lurks a radical proposition about deconstructing patriarchal and colonial systems.

It’s a considerable departure from Sleigh’s celebrated 2014 debut, Ad Lib, a hazy, surrealist satire of reality TV and contemporary pop culture, in which a bemused teenager, Kyla, inherits a round-the-clock camera crew filming a reality show about her in the wake of her famous mother’s death. By contrast, Women in the Field feels stately, controlled, almost deceptively straightforward, although it shares with Ad Lib a preoccupation with the visual. At first Women in the Field seems conservative, all buttoned-up cardigans and posh accents, but beneath the surface a lurks a radical proposition about deconstructing patriarchal and colonial systems.

In between the two books, Sleigh became a mother. The seismic rupture of parenthood, the way it turns your life inside out, rearranges your priorities, and brings to the surface the subterranean faultlines of patriarchal structures will be familiar to many. No surprise, then, that ideas of feminism, women’s creativity, and motherhood are woven into the fabric of the novel.

Holly Walker: Where did this book come from? What was the genesis?

Thomasin Sleigh: The first thought that came into my head about the book was encountering the fact that there had been real people with the job of buying European and British art for New Zealand. It seemed quite strange and abstract that there would be people doing this from afar who had never been here. And, there was a woman called Mary Chamot, who I became quite interested in, living in London and buying paintings for New Zealand, from the 1960s and into the 1970s. I don’t want people to think that Ruth Bishops is Mary Chamot. I pulled back the time period, and it’s not Mary’s life. But because of Mary’s advocacy in the 60s for a lot of modernist painters and women artists, Te Papa actually has this really incredible collection of modernist painting by women and quite progressive artists.

HW: There’s correspondence in the book between Ruth and the curator of the collection back in New Zealand, and I was struck by how deferential he was to her expertise, while masking how controversial the purchases were. Did you read similar, real correspondence in your research?

TS: Yeah. Again, it was a balance – because I’ve never written historical fiction before – of trying not to learn too much about the real people so that I didn’t write their story, but I did read a lot of correspondence, mainly to get tonal stuff and just pick up interesting historical things it would be good to throw in to flesh out the feeling of the 50s.

HW: The events of the book are imagined, but were there similar controversies?

TS: New Zealand in the 1950s was very conservative, very monocultural, very risk-averse. There is an interesting example that’s often used: in the late 40s the Christchurch Art Gallery was offered an important painting by Frances Hodgkins, Pleasure Garden, and they rejected it on the grounds that it was just too out there.

HW: How did you approach describing the fictional paintings? Did you have a clear idea in your head of what they looked like, or did you invent them as you wrote? Or look at existing works?

TS: The translation of art into writing is one of the mini-themes of the book. It’s probably quite autobiographical since that's what I spend a lot of my time doing and thinking about. The scene at the lecture [in which technology fails and Ruth and Irina have to describe the paintings to a waiting audience] was a good vehicle for that, because I had to describe the works by writing that scene, and Irina and Ruth also had to describe them to the audience. For the Women in the Field paintings I had images in my head that were amalgams of the work of several Russian women painters – kind of a tone or a style, rather than the specific layout of the paintings. The book is intended to show the limits of language in this sense, that every reader will see the paintings in different ways.

HW: When did the idea of using these characters and this time to explore women’s creativity come into it? Was that there from the start?

TS: Yeah, it was. I got really interested in early-20th-century painting by Russian artists, because there were a lot more women artists working in that milieu – much more so than any of the contemporary avant gardes in France or Spain or anywhere else. I started doing a lot of reading about this cohort of Russian painters and why it came to be that there were so many women working there at that time. Then I came up with this idea of pairing this creative struggle of Irina’s to get recognition with imagining Ruth’s working life. Any woman now will know what that’s like, just being in a meeting with all men.

HW: We learn that Ruth has been to art school, and started out as a painter, but has decided along the way that she wasn’t supposed to be an artist; she was supposed to be someone that writes about and thinks about and works with art. Of course, not everybody in the world is an artist, but I wondered whether in some sense she was self-limiting. Did you think of it that way?

TS: I didn’t actually, and that’s really interesting, because when I think about Ruth as a character, she does self-censor, and she’s quite reticent. I think that’s a really cool reading of her character. We hear it a lot in feminist rhetoric: we learn by copying; in order to become or do something, we need to see it. If Ruth had been walking around the Tate or walking around the National Gallery at that time, those places would not have been filled with women artists. There might have been one or two.

HW: Yes, and in her initial encounters with Irina it felt like she had internalised some of those patriarchal value judgements about art, because she initially dismisses Irina as a “minor artist” of no particular significance.

TS: I very much wanted their relationship to be complicated. I didn’t want it to be an epiphany – “Oh, this incredible artist walked through the door.” I think art history, as a discipline, is riven with those kind of myths, and I wanted to break some of those down.

HW: Ruth’s experiences at work – being the only woman in a meeting, things like that – made my blood boil, not only because of how she’s treated by her male colleagues at the gallery, but also because she’s quite passive in the face of it. She’s an interesting character, because at other times she’s quite forthright, and in some situations she does stand up for herself.

TS: It was really tricky actually, some of that stuff. I was very cognisant that Irina and Ruth weren’t feminists. That word didn’t exist and all the history of feminism that we know obviously just hadn’t happened. I think they could be aware of the constraints that were on them, but they would think about them differently than we might. I think some of Ruth’s reticence came out of that: at the back of my head I was saying, “She doesn’t think about women’s power or agency in the same way that I do.” Which is not to say she doesn’t think about it, but she just thinks about it differently.

HW: Another of the themes of the book is motherhood, and the different choices that the characters have made. We’ve got Irina, who’s concluded that she can’t be an artist and a mother, they’re not compatible, and Ruth, who doesn’t really seem to have thought about it except that maybe in prioritising her career it just hasn’t eventuated. I’m aware of course that you had a young child while you were writing this. How did that feed into the process?

TS: I think in 20 years I’ll look back at this book and think, oh, this is the book I wrote when I was going “What the fuck is happening!?” I had a young child and it’s just such a mind mash. Your brain has changed, your body has changed, the whole structure of your life has changed. I was thinking a lot about where women have been placed in society, to be the predominant caregivers, and what this has meant for our creativity, and our productivity. All these ideas that I’m sure every woman thinks about when they have a child!

I had a young child and it’s just such a mind mash … I was thinking a lot about where women have been placed in society, to be the predominant caregivers, and what this has meant for our creativity, and our productivity.

There’s this great essay by Linda Nochlin that you read in Art History 101 when you’re doing feminist methodology, called ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ It was written in the early 1970s, and she basically steps back and takes a structural view. She says women weren’t allowed to have studios, they weren’t allowed to go to classes, all this structural stuff that constrained what they could do. I was thinking a lot about what that would mean in contemporary society. You’ve written about it as well in your book [The Whole Intimate Mess: Motherhood, Politics, and Women’s Writing], all those structural things that may seem not important, or beside the point, but actually add up to a real framework for how we have to live our lives.

HW: But they’re very difficult to pin down, when you try to describe them. When I think about my time in Parliament for example, when people ask me in what ways was it sexist, or not set up to support women, I struggle to identify them, even though I know my experience of having a child in that environment was very different than it would have been for a man becoming a father for the first time. It’s very slippery.

TS: I think that’s just like thousands of years of patriarchy, essentially. It’s like a coral reef of decisions that have been made by men over time as to how things are structured, how decisions are made. As you say, that’s hard to unpick.

HW: Was that the reason for including the four-year-old twins, the boy and the girl, in the novel? I was fascinated by the tiny, subtle differences in the way they were spoken to by the adults in their lives. On a given day, it doesn’t particularly materially influence their experience if the boy is roughhoused and thrown up in the air and the girl is patted on the head – they’re still both going to have a nice day, but over the course of their lifetimes, those things are going to accrete, aren’t they?

TS: Yeah, totally. And I wanted to throw them in just to show how women can have different kinds of relationships outside of the conventional family structure. Obviously Ruth doesn’t have children, but she gets a lot of joy and love and affection from her niece and nephew and she has warmth from her family in that way. In the 50s you might see a single woman and make assumptions about what she’s like but those are incorrect, she had this other quite rich family life with her sister.

HW: You mentioned Ruth in the context of her family, and I found the scene where she discovers that her father has read her book, but hasn’t said anything because he feels like he might say the wrong thing, very moving. It’s beautiful, he’s proud of her, but there’s a loss in it as well.

TS: It’s funny, some stuff in the book you can never quite pin down where it came from. I did want to weave in a little bit of class discussion in order to give Ruth, who obviously already has various issues contending with the difficult men she works with, another slight awkwardness in the high-art world that she lives in. To be honest I don’t fully understand this stuff because I’m not British. But I have lived in London. I worked at the National Gallery, and I saw that in the UK, to work in the arts, you have to come from a lot of privilege. In the 50s for sure it was quite a snobby world. I wanted Ruth to come at that from another oblique angle so she could see through it a bit, so I had her come from the upper working class. Her father is a barber, who, like a lot of people, feels a bit confused by contemporary art, doesn’t feel like he can say the right thing about it, but as you say, still recognises that Ruth has achieved a lot. Also, her parents just have a very traditional view that she should get married and have kids, as I imagine a lot of people did in the early 1950s.

HW: Or still do.

TS: And still do, yeah! They struggle to value her professional achievements over the familial achievements that they think she should aspire to. A friend of mine who is a curator said she cried in that scene as well, because she has had similar experiences in her work and family life.

I’m not British. But I have lived in London. I worked at the National Gallery, and I saw that in the UK, to work in the arts, you have to come from a lot of privilege.

HW: Then of course she gets on a boat and comes to New Zealand. The first part of the book we don’t see much of New Zealand, we’re seeing it filtered through what the colonial view of New Zealand might be. How did you imagine Ruth’s unfolding encounter with this country?

TS: It was actually really fun doing the research for that. I found this weird little pamphlet in the university library, which was a young boy’s account of emigrating to New Zealand on a boat in 1952. I just read that, which was really funny, and written from a child’s point of view. I wanted to write this weird boat scene, this liminal chapter, sort of the hinge that the book sits on. And yes, as you’ve picked up on, the emerging of New Zealand through Ruth’s imagination. I thought about that a lot with the real people who worked in this job in the 60s and 70s. Some of them did come here, and it must have been really weird seeing the works that they had purchased in context here, and learning something about this place.

HW: It's clear from reading the book and listening to you talk just how much historical research has gone into it. Why choose a novel for the expression of that research, that interest in those ideas and themes and history?

TS: Firstly, I would say that the research was very on the fly! It wasn’t like I got out a bunch of books and was like, “OK, I need to know everything about the 1950s.” It was like, “Oh, I’ve got to know this thing.” If anybody who actually knows stuff reads it they probably could see a lot of inaccuracies. But it’s a really good question, like why write a novel rather than write, for example, Mary Chamot’s biography. I enjoy creative writing so I wanted to write a novel, and I’ve always had a slightly funny relationship with art history as a discipline, so this was a way of writing a bit outside of that.

When you’re writing from a feminist lens you have to imagine a different world. A totally different world

I’m working at the moment on a piece for the painter Emma Fitts, who has a show at Te Uru in Auckland, and she’s also really interested in the way women artists are depicted or understood within the very male discourse of modernism. In some ways, when you’re writing from a feminist lens you have to imagine a different world. A totally different world, if women were making the decisions that men have always made, it would be such a different place. It’s a kind of imagined art history. Which is problematic, and I often ask myself ethical questions about making stuff up. And that’s my cautiousness about always being very clear that this story is not true, that it doesn’t reflect what actually happened, because there are ethical implications for that.

There is one name that I haven’t mentioned yet – a Russian painter called Natalia Goncharova. After very little acclaim during her lifetime, she’s since become the most expensive woman artist to sell at Sotheby’s. The Russian oil oligarchs are buying all her paintings. Te Papa has this incredible collection that today would be worth billions of Euros because Mary Chamot really loved her painting. Ruth is not Mary Chamot, and Irina is not Natalia Goncharova, but she’s kind of an amalgam of all those Russian women painters.

HW: And I liked the idea that she had this weird, in a way, recognition in her lifetime, in your novel, that she had these paintings that became the centrepiece of a national collection, but it was in New Zealand, of all places.

TS: Yeah. And I love that – every art collection will have these very weird stories. You think of it as a kind of neutral professional process by which things are acquired, but there’s all these weird human behaviours and strange decisions that create this national collection.

Header image: Thomasin Sleigh, 2019. Photo: Hannah Newport-Watson

This piece is presented with support from