Destined for Extinction: Elam's Huia House

What happens when someone gives some art students a house?

What happens when someone gives some art students a house?

There is a house in Huia that once was the talk of Auckland’s young art community, but in recent years it has disappeared from all conversation. Until now.

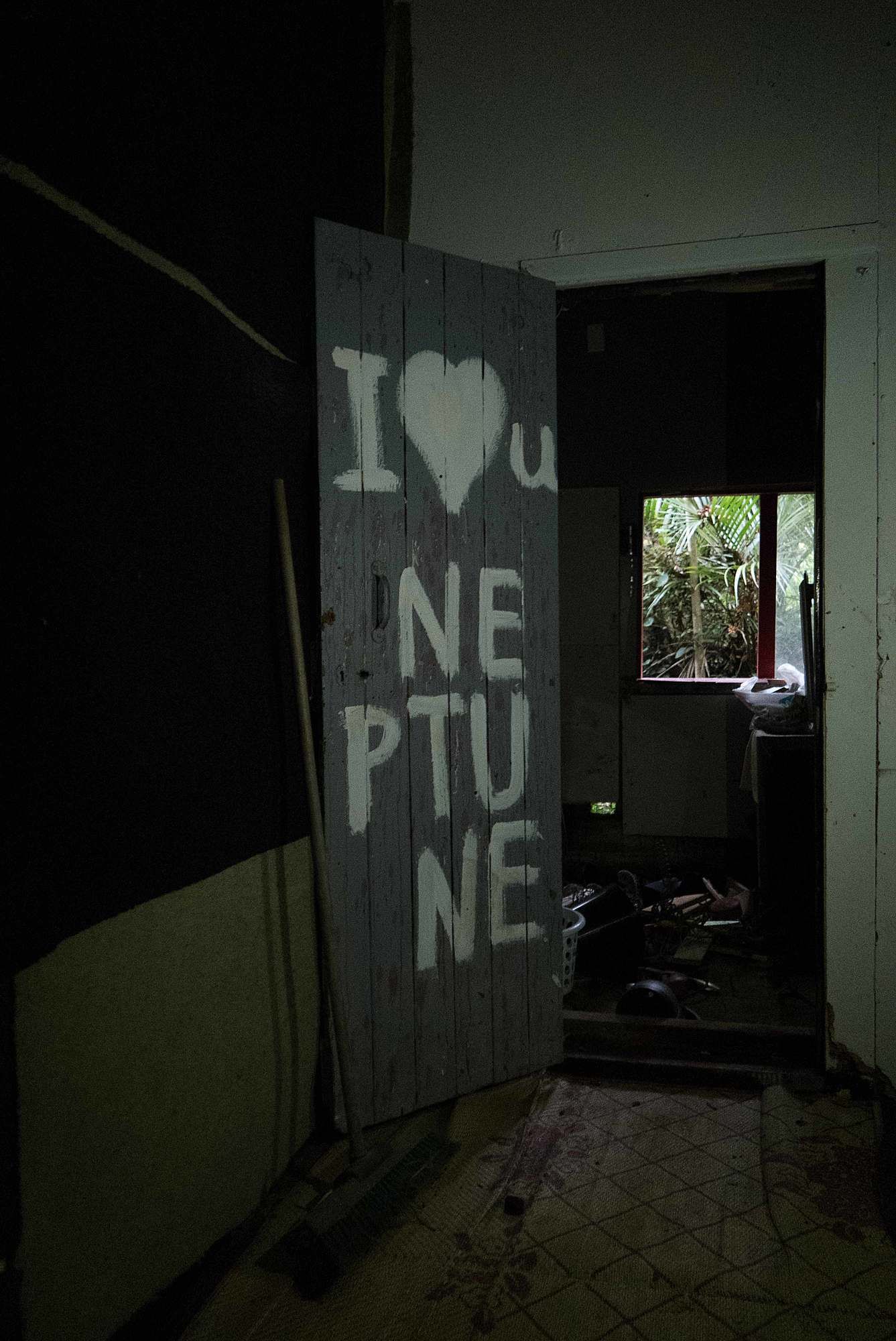

Through ferns, tree trunks and leaves appears glimpses of a vibrant blue. The house’s front door is boarded closed. The air is heavy with water. A microwave waits at the front step next to an “Access Restricted: Do Not Enter” sign with “contact the University of Auckland Security Control Room if access required” written in small text underneath. Inspecting the outside of the house, there are gestures that allude to its history. One small window has a wooden frame with indents carved into it. On the left side of the house there are two red figures painted onto the wall. Underneath the water tank on the right side is a mess of fairy lights and a discarded hand painted sign reading “Neptune”. It seemed we had arrived late to the party – several years too late.

The house with the vibrant blue front has been referred to by various names over the decades – the Fisher Lodge, the Huia House and the Elam House. Its long history is hard to pin down.

The land that Fisher Lodge stands on was left to the Elam Student Association (ESA) by Archibald Joseph Charles Fisher, who died in 1959. On news of his death, an Auckland Star columnist described him as “a most outspoken man with strong views on many things, and he made enemies, for he had an uncompromising regard for what he considered to be the truth”.

Fisher studied fine arts at the Birmingham Municipal School of Art and at the Royal College of Art. In 1924, he became director of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Art. Fisher transformed Elam from a day school for adolescents to a full department of Auckland University College. It is not clear what his long-term intentions were in leaving Fisher Lodge to the ESA, but it seemed that he had great ambitions for Elam. Perhaps then he saw the house functioning not only for art making, but also as an important asset to provide long term support to the students at Elam.

After the land was bequeathed to the ESA, a student built a house on it, purchasing materials out of his own pocket. He got into money trouble and the ESA had to raise a loan to reimburse him, with two other students’ family members acting as guarantors. A decade or so later, the house had already begun to deteriorate. In the 1970s, there was an architecture project to restore the interior of the house. In 1972, the ESA asked past students, staff, gallery directors and others for donations to help the house. In the same year, a family temporarily resided there.

It is difficult to get a full picture as to how the house was used and who used it over time. Colin McCahon hung out at the house and was rumoured to have painted one of its doors that was later stolen. Derrick Cherrie (Elam’s Head of School) and James McCarthy worked on the deck and long drop. Megan Jenkinson (an Associate Professor at Elam) made a lead light for the house. In 1992, Gavin Hipkins lived alone at the Fisher Lodge for 12 months contemplating the new age, postmodernism and art photography. “Here, a magnificent kauri grows through the lodge's deck and a valley of tui sing near the stream,” he says of the house in an article for Landfall Journal, which was republished on The Big Idea. He also describes his commute to Elam from the house: “Cycling through darkness without lamp (knowing well the few kilometres of winding quiet road) to reach the one departing bus at 6.30 A.M. for the hour-long ride to K Road and art school was an easy path, except when the river flooded and mudslides blocked the road.”

The struggle to stop the house from deteriorating started early in its life. It may be something to do with how it was made; it may be the lack of money had to maintain it. I think too, the transient nature of the ESA itself affected the house’s long term survival. Most students only attend Elam for four years, and only a handful are involved in the ESA and usually for one or two years at the most. How the ESA operates depends almost entirely on the motivation of the students who run it.

Bryn Roberts and Tim Wagg ran the ESA between 2012 and 2013. They were part of the last solid effort to raise money and awareness for the house. Roberts had heard rumours about the house while studying at Elam. In her second year in 2011, Sophie Bannan, an acting ESA president, asked Roberts to take over the ESA, which involved learning about the house. “The University never had any authority over the house, that was the beauty of it. It was gifted and belonged to the Students Association which is totally separate from the University.” Wagg also believes the wider political context at the time, which involved significant conversations about asset sales and voluntary student membership for students’ associations, contributed to the desire to keep the Elam house.

Roberts turned her time as president of the ESA into her own project. When Roberts took on the role, the house was occupied by an Elam graduate and his family. He paid $40 - $60 per week and had lived there for several years. Roberts believed the house should be made available to students again. “My final work was a ‘performance/event’ where I drove my tutors out to the house (it’s almost an hour from Elam), telling them an oral history of the house on the way. When we arrived, I handed an eviction notice to the tenant, who it turns out was an old student of one of the tutors. He invited us in for tea, showed us around, we all talked about the house and our future plans for it, then drove home. I’m not sure how I feel about that work now.”

The University never had any authority over the house, that was the beauty of it. It was gifted and belonged to the Students Association which is totally separate from the University.

Although a tenant had been living in the house, it was in a bad state. “There was no hot water, the bathroom was outdoors, there was electricity, but no phone or internet (and no cellphone service), and the deck was almost rotted through. Some windows were broken and it was draughty, but the pot belly fire worked.”

As others before, Roberts and Wagg envisioned the house becoming a place for students – either for events or short-term residencies. They ran events out there, spent weekends there, hosted working bees for the house and organised fundraisers.

In 2013, part of the funds raised at the Elam Art Fair were used to cover rates expenses and the cost of installing a rainwater collection system. The press release for the event stated, “The students’ association is putting major effort into restoring the property to a usable condition, hosting events and class gatherings at the house, which is available for student use at a reasonable nightly rate. Once further work is done, the association hopes to establish a residency programme and to offer night classes and weekend workshops at the retreat.”

But as Roberts asked builders to inspect the house to work out what needed to be done, she realised its issues ran into its foundations. “They agreed it pretty much needed to be rebuilt.” Without a budget and with only those in the ESA looking after the house, the few working bees they ran only temporarily fixed some cosmetic issues with the house. People outside of Elam started to think it was abandoned.

One night, Roberts went out there alone. She was nervous about having no cellphone service. Although she found it peaceful, she later learned that a bathtub was stolen off the property the same night she stayed there. “Another time I was out there with my friend and fellow student Robin Murphy. Again totally isolated, no phone, no reception, no internet. We had been out there a couple of days and were watching Twin Peaks in the dark when we heard a car pull up and some people walking around the house. They walked right past the front door so I opened it and they came back up”. The two young men asked Roberts if the house still didn't have a phone. They said they wanted to come in, they knew someone who used to go to Elam. Roberts asked them to leave.

After Roberts graduated she stopped being involved with the house. However, she returned recently to reminisce on the times she spent out there. She was startled by the warning signs taped around the house. Without students realising, Auckland University had decided to send someone to board up the house and pocket the key.

This year the ESA have decided to modernise their constitution and strengthen their structure to make the ESA a proper reinstated association. This will open up funding possibilities for the ESA, including seeking funding from the Auckland University Students’ Association. As the ESA critically evaluated itself, it was confronted with a startling predicament. They learned of the $500,000 property they owned 45 minutes away in Huia. They also learned the house on the property was falling apart.

The current ESA vice president, Olyvia Hong, has her end of year project looming and a house on her hands. I met Hong at Elam on a weekday evening. Like others in recent years, she hadn’t heard about it until took on a leadership position in the ESA. “The matter of the Huia House has never been resolved because every year there has been a new president,” she says. After receiving pressure for the faculty, Hong started researching options for the house. These included selling the house and setting up scholarships from the proceeds, setting up a new space closer to Elam with the proceeds, fundraising to rebuild the house, or renting the house out. But she had never seen the house, whose fate she was soon going to ask students to vote on in the next month.

I invited Hong to join a past ESA vice president, Tim Wagg. Since he graduated, he hadn’t been to the house again. On a Saturday morning we set off from Elam on the long car drive to the house. The conversation drifted into changes at Elam since and whether students were reacting to the political turmoil of this year in their art. The city around us rolled into suburbs intersected by narrow, congested roads, which eventually gave out to bush.

As we arrived in Huia the road wound around the coast and was flooding in parts. A few minutes up the road from the shore was a scattering of houses each surrounded by dense foliage. Wagg stopped at the end of the short driveway leading to Fisher Lodge. It appeared as a ghost.

The house is three stories tall, with a small water tank on the house’s right, and two balconies on the second and third floors. Down a small slope out the back is a long drop. The gutters were filled with leaves, the windows and doors all boarded up. It looked soaked through.

We walked around the outside of the house then slid in through a broken window. With cell phone light, we examined what was: a gig space on the bottom floor, crooked stairs leading to a kitchen, lounge, then another floor with bedrooms.

Looking around the house, which had traces of the exhibitions, gigs and parties that once occurred, Hong finally saw the house that had taken up so much of her thinking in the past few months. For Wagg, the experience seemed both nostalgic and to provide closure.

The ESA’s house at Huia most likely shares the same fate as the native bird. But there is the hope that in its extinction it will be able to live on in different forms, supporting the students at Elam for as long as it possibly can.

Alyson Hunter

Elam Student 1966 - 1969

I lived in the house for some weeks with my friend Alison Cavell. We painted it white inside. A possum came in and was defensive as we shouted in fright. I threw my paintbrush at it and it ran away with white paint all over it.

We read Van Gogh's letters to each other. We went to the beach to dig for pipis. We did not have much to eat. An enormous spider was king of the outside lavatory.

A large man one night appeared at the front door. He said in a slow voice he wanted to help us. That it was for us; we were tired, damp and hungry. In the morning, we were on the bus back to Elam. It was good for us, we appreciated a lot more after that.

Interesting you say about the lack of internet there. The point, as I remember of the place, is for the space for mediation and to find yourself. I remember the birds singing and the quiet. The smell of new growth bush and the rot of the bush floor. Huia itself seeming an outpost like many in New Zealand, forgotten and reverting to another time, not somewhere an hour from a spread-out city.

Now I am 68 most of all I remember the excitement of the sixties in Auckland and the true friendship of Alison and all the students of Elam of that time. How groups of us would go out and try to have a commune with different jobs given out. But putting my builders hat on, it was built by a student, but even a fine design made cheaply cannot sustain itself in the damaging clawback of the bush.

Perhaps sell half the land and use the money to buy a prebuilt log house for a small section to be used as a retreat and studio with internet and modern comforts. AirBnB it to pay for the upkeep? Pay a local person to change over. Although not the man with the slow voice!

If you have your own stories about the Elam house that you would like to share, send them through here.