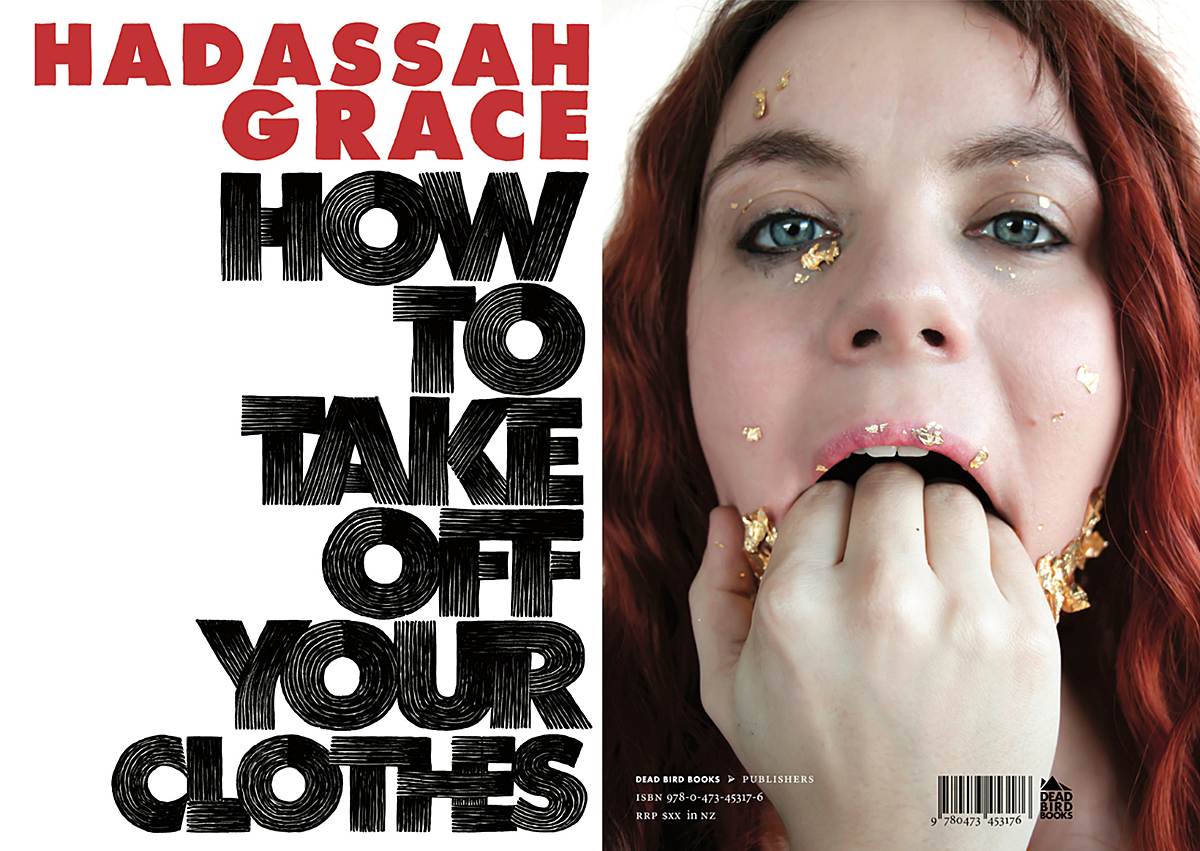

Bad Men and Bad Women: A Review of How to Take Off Your Clothes

Hadassah Grace’s debut book of poetry captures the voices of women in the sex industry and beyond. Carolyn DeCarlo reviews.

Hadassah Grace’s debut book of poetry captures the voices of women in the sex industry and beyond. Carolyn DeCarlo reviews.

Hadassah Grace’s debut book of poetry, How to Take off Your Clothes, is upsettingly relatable. As I read, I was reminded of my own early 20s, and some of the more horrific events that took place in my life and the lives of my friends at that time. Although most of the events she describes take place in New Zealand, whereas in my early 20s I lived in Baltimore and Washington, DC, in the United States, they nonetheless carry a familiar weight and mood. This book is not meant to be a comfort to anyone, except perhaps as a reminder that you are not the only person with problems, your problems are not unique and there are people in this world who are having a tougher time than you are.

Grace has spoken candidly about her book being autobiographical. However, as readers we get the sense that she also hopes to capture the voices of other women, fictionalised or real, as often the voice of the poems is a collective one, expressed in the first person plural “we/us” in poems such as ‘Ruin’:

you will know us by our full mouths and empty bank accounts

by the dirty plates on our floor and the toothbrushes in the depths of our handbags

by the scuffs on our combat boots and the chips in our polish

by the lipstick, and fake tan, and salt marks we leave in your sheets you will know

we are ruined women, and we are here to ruin you.

It is a call to arms for her fellow women against all forms of assault and aggression, and maybe, even more, a warning to those who would perpetrate such harmful behaviour. Without naming or even gendering the collective “you” addressed in ‘Ruin’, Grace evokes a familiar dichotomy: “we” are the women and girls, ruined by “you”, the bad men. This theme is not unique; by now, maybe it has even become a trope, but we are still living in a world where there is value in its repetition. Every story has its own narrative, and each one is equally worthy of being told and heard.

Grace’s book serves as a reminder that not every woman follows a traditional narrative across her lifetime. In ‘Men Who Paid to Touch Me (found)’ the reader understands that these lines have been transcribed from things said directly to the writer (or other women), while working in the sex industry for a primarily male clientele:

I’d tip you but you’re only worth about fifty cents.

You’re incredible, take all my money.

Will you marry me?

Don’t you think you should lose some weight?

At least your face is pretty.

You’re too fat to be a stripper.

Your body is amazing.

While some within the patriarchy would say the woman being addressed in this poem is ‘asking for’ comments like these, informed readers recognise fat shaming, body shaming, and both emotional and mental abuse entrenched in the found language on the page. Sex work may be legal in New Zealand, but it is treated as seedy, immoral and worthy of deprecation by the very clientele using its services. By using found language to craft her poem, Grace has harnessed an incredibly smart way of portraying this kind of hostile, male-perpetrated behaviour, and its exposure leaves a lasting impression.

Grace doesn’t let men take all the blame. In ‘Lite Switch’, it is the woman who seeks the bad man:

narcissistic neurotic nymphomaniac

seeks physical manifestation of the patriarchy

must love rosy cheeks and dirty mirrors

Whether the language in this poem is meant to be tongue in cheek or taken straight, the reader is encouraged to reconsider heteronormative approaches to blame. In this scenario, and elsewhere in the collection, it is not always the woman who is the victim. Is this feminist? There is feminism in the text, and it is easy to read feminism into passages like this one, where, while the women are behaving badly, this is encouraged by the idea of the feral female, the wild woman, the self-proclaimed descendent of witches. These jaded, sexualised ‘bad girls’ are operating on their own, doing what they want, when they want.

I have never worked in the sex industry; many other readers won’t have either. This does not keep Grace’s writing from being readable, relatable, digestible; on the contrary, it is not difficult to find ourselves connecting to her writing: “Yesterday I thought I loved you. Tonight I hate you. Tomorrow, missing you will be a knot in my stomach and an ache between my legs.” However, as the reader progresses, they face a real danger of becoming numb to the violence and aggression present in this work. In the context of such an onslaught of expected male behaviour (and inherent gender binary and heteronormativity), lines in later poems, such as “this is not a poem/ it’s a rape joke”, from ‘women>pain’ fall flat. Is this meant to shock? To be fair, at this point, not much would. There is a dangerous singularity to the poetry in Grace’s collection, a fixation in tone and subject matter that lulls the reader into a false sense that these destructive gender dynamics are inevitable.

Unlike most of the poems in this collection, ‘45’ makes an explicit admission or claim to truth: “when I was four, my brother fed me superglue. / not a metaphor, just a true story.” The reader immediately finds this poem trustworthy because Grace has declared it to be so. Yet, in many ways, this poem is one of the most far-fetched: “he told me it was liquid candy, full of vitamins to make my / muscles grow. I squirted the whole tube into my mouth. / … / I remember starting to chew, and then my teeth stuck together.” This is a horrible truth, if it is one – and why wouldn’t it be? On the surface, the speaker has revealed herself to be recalling a memory from when she was four. But most likely, part of this ‘memory’ isn’t a memory at all, it is a story recalled by an older family member and told to the narrator in detail, perhaps with photographs. Its truth is a lie. Perhaps counter-intuitively, the result of this is that the other poems – the ones about women in trouble with men, adults using sex for power, the weaponisation of the word ‘witch’ – gain a sense of relative reliability against those who would question them. No one is prompting Hadassah Grace to share those stories; they all just come from a sense of inner truth.

With the rising trend of movements such as #metoo, I propose it is their ordinariness and relatability – their inner truth, which speaks to all who have ever been labelled as ‘victims’ – that gives them their strength.

In a world already crowded with trauma poetry, are Hadassah Grace’s poems innovative? And are they necessary? The very same language is being thrown around in the news, on Twitter, and even by the President of the United States. So what, if anything, makes her poetry unique? Perhaps setting confessional-style poetry up on a pedestal is no longer an effective way to read it, nor is it effective to think of these poems as innovative at all without danger that the label will simultaneously diminish them. With the rising trend of movements such as #metoo, I propose it is their ordinariness and relatability – their inner truth, which speaks to all who have ever been labelled as ‘victims’ – that gives them their strength. By calling these poems mundane and folding them into a longstanding tradition of women’s writing, rather than setting them up as new and innovative, only then will they gain their full power. Grace’s poems do not break the mold, they fit it – this audacity is what gives them their value.

Hadassah Grace, How to Take off Your Clothes (Dead Bird Books, 2019), $25