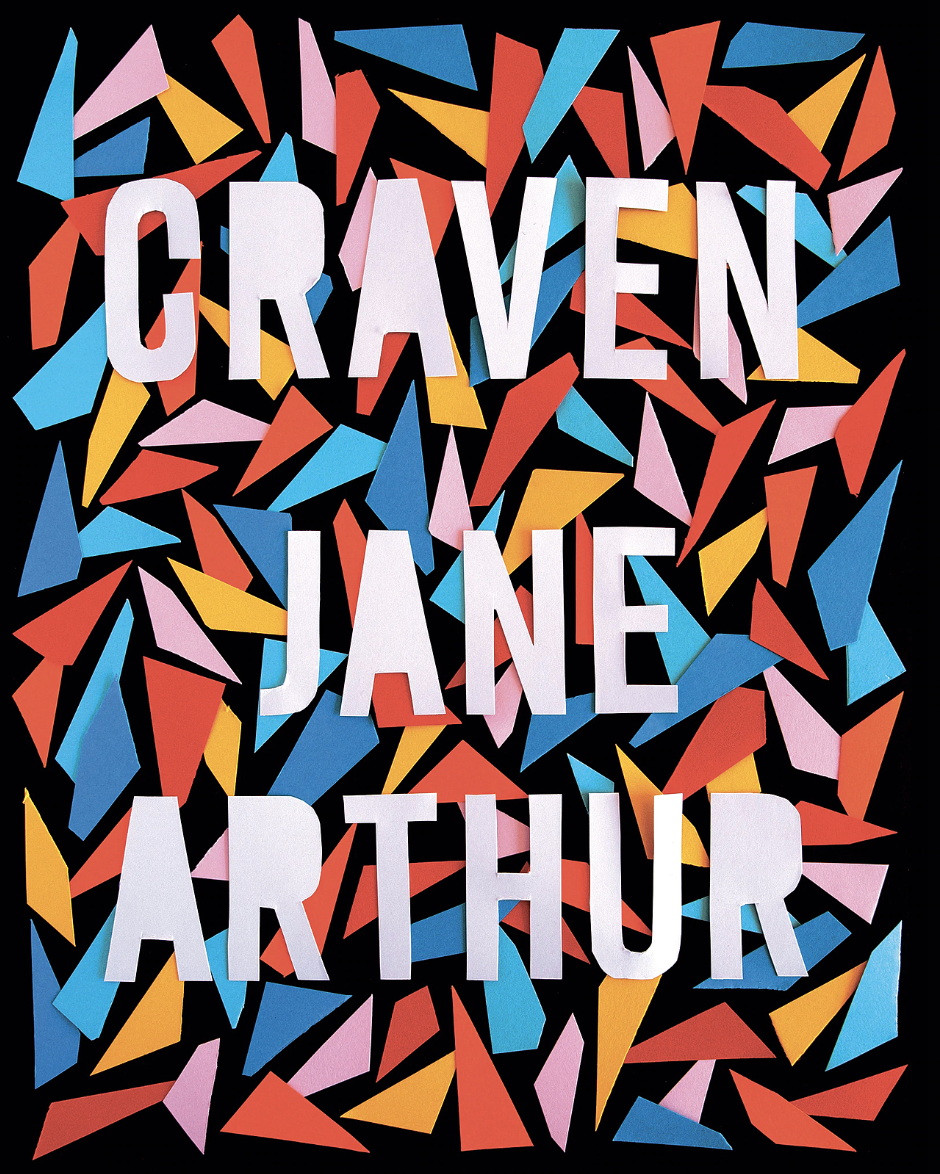

How to Read My Poem: Jane Arthur

Jane Arthur takes us under the hood of her poem, ‘The Real Reason Why Hollywood Won’t Cast Jane Arthur Anymore’, from her book Craven.

Welcome to a new series in which our favourite poets take us under the hood of one of their poems, inspired by the How to Read My Poem session at Verb Festival.

Jane Arthur explains her phobia of sincerity and the experience of writing through the daze of new parenthood, in the story behind ‘The Real Reason Why Hollywood Won’t Cast Jane Arthur Anymore’, from her book Craven.

About a year ago, I was a year into being at home with my baby as the primary caregiver. It was the first and only time I’ve been out of paid work since the age of 14.

At the time, and still now, I’m not interested in writing about motherhood directly – I’m not sure why, exactly, but I suspect it’s my slight phobia of sincerity. Or my inability to put the experience into words. Or my suspicion that no one else actually cares about your baby; a bit like if you tell someone your dream. Who knows?

But that time did inspire my writing in more oblique ways, because it was this giant pause button on my life. While I’ve had various chapters and beginnings and traumas and mistakes and accomplishments throughout my life, none of them stopped the rest of my life from chugging along. I still had to go to work, or write an assignment, or buy bread, even if depression found me bed-bound for a while – there was some kind of forward momentum.

But the first year of my son’s life, all of that stopped. It found me inside, day after day, trapped under him. I’d carry him through the house, making tea one-handed, breastfeeding him, having him sleep on me for all his daytime naps: my body was no longer mine – profoundly – and by extension my mind was sort of held prisoner, because it could only reach as far as the confines of the house, or Netflix, or Twitter. It didn’t have the energy to engage intellectually with what was happening in the world – it was too sleep deprived, and too switched into the cadence of nursery rhymes and nappy changes.

So I saw glimpses of #MeToo and Weinstein and Trump and atrocities of men and anger of women, but I couldn’t engage because my skin felt inside out. I wasn’t even postnatally depressed. I was just tired. I had created an entire human inside me, and was keeping it alive in the world, and didn’t know how to leave the house without half a day of prep-work and forward planning, and I was full of sheer terror about raising a child – a son – into this evil, dire, doomed, patriarchal, burning future.

I was subconsciously processing cancel culture, and getting stuck on where the lines were.

So I disengaged, binge-watched comedies, read poems half-asleep, and let it all work away at my subconscious. And then I’d tap out drafts of poems one-handed on my laptop, while my son slept on me in the rocking chair. I didn’t give a shit about how bad my writing was. It was something achieveable, something that I could feel okay about having done at the end of the day, even though the dishes piled up and the bath was coated in scum, and I still hadn’t managed to shower.

And I was so tired. It meant my brain wrote out through a kind of dreamstate, and this poem really reminds me of all that when I read it now.

It’s anchored by three domestic images, here and now, with three household appliances and tidy, left-aligned shapes on the page – and then these rambling, ugly sprawling bits that capture that sense of my life flashing before my eyes, like having my baby was a bit like the death of me. The death of untethered, free me. I suddenly realised I wasn’t young, I just really wasn’t, I had whole histories that were decades old. Romantic mistakes from last century. My feminism had come leaps and bounds.

I was subconsciously processing cancel culture, and getting stuck on where the lines were – feeling fiercely about refusing the art of famous creeps, but what about my friendships with men who were less than honest with their ladies? But then I disengaged again because it felt so hopeless. So I’d ask questions without answers. I’d reassure myself that the world is complex and that’s okay. I listened, I read, I believed victims, I more or less shut up, and tried to get some sleep.

Small things were suddenly massive and important things were suddenly too hard, because I was changed and my organs were on the outside

I let myself write some naff and naive lines, as a way of accepting myself, of letting go of control and self-judgement – so there are some parts in this poem that I don’t like, but that kind of makes me like them more because I made myself keep them in. I let myself keep them in.

The title is a nod to the depths of internet crap I was finding myself clicking into – the clickbait it figured I was interested in, being trapped under a ten-month-old and looking at Perez Hilton’s coverage of the Weinstein story.

All these collisions of things in my world fed my writing – the way small things were suddenly massive and important things were suddenly too hard, because I was changed and my organs were on the outside, learning to crawl towards a future of pain and hopelessness and complacency, and getting older and older and older.

*

The Real Reason Why Hollywood Won’t Cast Jane Arthur Anymore

There are times

when it begins to rain

and I turn the TV up

to its loudest setting

but still I can’t hear it over the

frankly

flamboyant racket.

When I was nineteen I had a boyfriend, briefly, who

before I met him lived in the house where Darcy Clay had died

and thus far it was

my nearest brush with fame.

We never talked much.

That boyfriend was one in a row of boyfriends

I didn’t have much in common with,

fundamentally,

including the one who stepped onto a full bus with me

and loudly proclaimed, ‘Yes, but you know what

Heidegger thought’ or Kierkegaard or Schopenhauer,

it’s unimportant—

we’d been talking about lunch right before that.

Our whole short dating period was a non-sequitur.

Then there were lost connections and obsessions.

Or not having a boyfriend but getting asked out

and lying about having one instead of simply saying no.

That was during a window of time in which

I think I might have looked

more interesting—

by which I mean better— than I was,

but no longer. What a wee grief,

for your personality to take over your looks.

Over the years

I’ve found my comfort

in a variety of places.

Most recently in lifting the lid

to watch the washing machine

turn and splash as it fills with water.

Wet lint is caught

in the fabric softener dispenser

and I rarely clean it out

because I’ve become fond of its strata.

And over the years

I’ve come to some realisations.

It’s easier to defend your friends,

or forgive them,

or brush things off as

quirks of their personalities.

Even friends of friends.

It’s easier to condemn strangers for being shits.

It’s easier to believe wrongs

are too small to be bothered with

when they happen to you.

It’s true, sometimes they evaporate;

sometimes they are the pea under a pile of mattresses

or an undiagnosed tumour,

growing, pushing against other organs and

setting off seemingly unrelated symptoms.

It’s okay to make a big deal

Are you listening?

Imagine if dying really did involve Death,

a human-like figure, imagine if

someone in a cloak showed up, said,

‘Uh, yeah, sorry,’

and did that cut-it-out motion across their throat

with one hand while twirling their scythe in the other

and then,

I don’t know what would happen next.

Some dying.

Anyway,

I’m thirty-seven. By the time you read this, I’ll be

older. My face surprises me these days

and I’ve never liked surprises,

but lately they strike me more as a dull thud

somewhere in the distance,

like a car backfiring on a still day

when I’ve zoned out to the beat of the dishwasher

so I don’t really hear it until it’s long gone,

I mean my brain doesn’t process it at first,

and then I don’t jump,

I just shrug.

Jane Arthur’s book Craven is published by Victoria University Press (September 2019)

Photograph of Jane Arthur by Ebony Lamb