Summer Reading Series: How To Die by Jo Randerson

New fiction, non-fiction and poetry by Aotearoa writers to read over the summer. This week: Jo Randerson.

Each week over the summer we are posting new fiction, non-fiction and poetry by Aotearoa writers. This week, Jo Randerson shares her essay 'How to Die.'

Read the rest of the series:

'Drunk Girls' by Helen O'Connor

Two poems by Louise Wallace

Two poems by Vaughan Rapatahana

How to die

How do you imagine you will take your last moments of life? Will your spirit be at peace? Or terrified? Will you be lying, immobile, hoping that someone will come to your aid? Or will you literally fly up into the sky, raptured? Will it be like the movies: a big explosion, a car crash or a grenade? Would you be surrounded by medical equipment, your veins connected to saline drips and heart monitors beeping in the background? Or would you be free-falling? Off a bridge? Out of an aeroplane? Or might you be looking down the barrel of a gun?

Might you be desperate for water? Might you be drowning? Locked in a room? On a small boat? Will you be starving? Surrounded by loved ones? Would you be listening to your favourite Beyoncé song? Or alone in your flat, for several days, before your body is discovered? Might you be in an expensive hospice, with kindly folk singing as you cross the threshold? Did you ‘pass’ during a medical procedure, the accidental recipient of the wrong blood? Or was it your own inattention? A careless, casual, slip of consciousness with disastrous consequences? Will you die at the wheel? In the surf? Did you underestimate the importance of swimming between the flags?

Might you be desperate for water? Might you be drowning? Locked in a room? On a small boat? Will you be starving?

And furthermore, whose fault would it be? A powerful, uncontrollable disease – the Big C? AIDS? SARS? Another new pandemic – originating from cockroaches? Or terrorists? Or the result of poorly designed government policies that fail to assist those in need? How about flooding? A tsunami? Nuclear fallout? Or would it be ‘natural’? Did you just slowly and quietly wind down, at your body’s own pace? Will it be random? Or hastened by a life spent sitting in air-conditioned offices? Or low-grade stress from a racist boss? Anger that you ingested? Did your soul just give up somewhere along the line, because you lost faith in humanity? Did you have the wrong attitude? Or a vitamin deficiency? Death by no known cause? Loss of hope? Beaten down by the patriarchs?

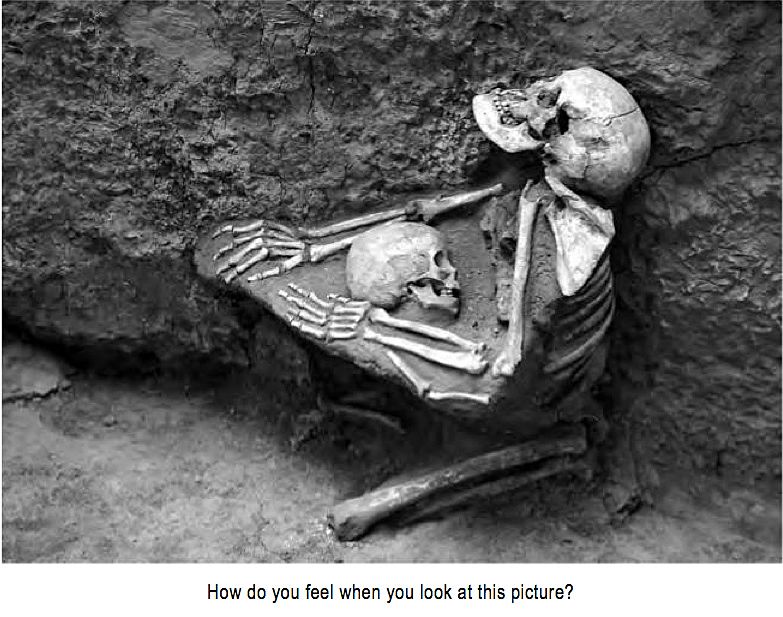

As a child, I was fixated on images of the remains of inhabitants at Pompeii. Their final moments as the heat and volcanic ash overpowered them. I remember seeing the body-casts of mother and child, frozen in their last minutes together. This image affected me deeply. It horrified me, but I knew that I had to keep looking at it.

As I grew older, stories of death continued to fascinate me; I especially liked to read about disasters. One of my favourite library books was a historical tome, called something like The Top 20 World Disasters. I would dwell on stories of the Church of the Company fire in Chile, the Tenerife airport disaster in 1977, the destruction of the Hindenburg, asking myself what I might do in those situations. Later in life, contemporary tragedies would haunt me. The Russian sailors who died in the Kursk. The Lonergans, tragically left out at sea on a scuba trip at the Great Barrier Reef. The inhabitants of the Chinese village Lajia, in Qinghai Province, who perished in earthquakes and flash flooding and whose remains were not found for several thousand years. The remains of two of these people are pictured opposite.

These kinds of fixation may seem morbid, unhealthy. But although we might feel that it is negative to think about death, some spiritual practices suggest meditating on one’s own demise, or the demise of a loved one, to bring ourselves into the present. One belief is that near-death experiences make us cleave more fiercely to what we value in life. Death can make us reflect on what is important, perhaps reconsider how we choose to spend our time. My father, who is a priest, counts funerals as one of the most important parts of his ministry. Funerals are times when people question their own choices and behaviours. This final goodbye can bring renewed purpose and focus to our lives – it can improve the quality of our relationships. People are often more loving and sensitive at times of death – we tend to care more tenderly when we are reminded of our vulnerability.

My grandmother was a florist. She told me that if a flower bulb refuses to bloom, you should put it into the freezer. The shock of the cold means that when you pull it out, it suddenly bursts into radiant life. This is a metaphor for how humans behave. Death is one of the best constructs we have been offered in this existence. If there were no limit to our days, there would be little pressure to do anything – there would always be a tomorrow. I work in creative contexts where participants need to create work in short time periods. There is no time more productive than that immediately following the ‘five minutes to go’ call. Engagement skyrockets. Productivity skyrockets. Group cooperation skyrockets. A limit can make us work harder – it can make the time more intense, more meaningful. I love my life, don’t get me wrong, but I don’t want it to go on forever. I see myself as a runner in a relay race, just carrying the baton for a short time, part of a team effort.

Death is one of the best constructs we have been offered in this existence. If there were no limit to our days, there would be little pressure to do anything.

Although I found a kind of ‘working peace’ with my death fixation, it has flared up again in the past decade. When I worked with the Royal Society in the 2000s, writing and researching on climate change, my existential anxiety found a new flavour. Extreme weather. Food and water shortages. Mass panic. Societal collapse. I was reading Jared Diamond, Ronald Wright and numerous other writers, researchers and climate scientists. I found it hard to sleep at night because I was so worried for the world. The demise of large numbers of humankind. The extreme vulnerability of the earth. The deeply concerning inequality of our planet’s climate change.

This anxiety became compounded when I had children. There were not only the standard parental fears about my children’s health and well-being, but also the possible dissolution of the whole system on which we depend for our lives. If the kinds of extreme scenario that were being predicted came to fruition, how would I explain to my starving child that there was no food coming? That we would just have to hold each other in our arms, while the pain increased, until our bodies lost consciousness? And I recognise my privilege that I have never yet had to face the kind of grim scenario that many inhabitants of our world experience daily.

Although, as my grandmother said, the cold can make flower bulbs (and humans) bloom into life, it can also have the reverse effect. Nietzsche said, in Twilight of the Idols, ‘What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.’ If it doesn’t kill us, it makes us stronger. But it can sometimes kill us, either literally or by freezing us to inaction. The horror, the impossibility of the challenge, can make us close down. It can make us put our head in the sand, ostrich-like, to try to deny the severity of our situation.

There is a strong bass chord of fear underscoring contemporary life, and for many people I know it has paralysing effects. We are overloaded with information — we are saturated with headlines about melting ice caps, the erosion of natural habitats, pollution, plus all the related social concerns: inequality, poverty, and the dominance of global mass-culture. And what do we do in the face of these facts? Do we hole up, make the best of what we have until the last moments?

Consider this description from a review of the film Downfall, chronicling the last days of Hitler’s World War II regime, in the Führerbunker in Berlin. The film follows the final weeks of Hitler, Eva Braun and his cohorts as the Allies closed in around them. As the likelihood of a positive outcome for the Nazi regime faded, life inside the bunker became increasingly focused on pleasure-seeking.

Adjutant Bernd Freytag von Loringhoven recalls how the bunker complex was full of gourmet food and spirits, in surreal contrast to the world outside. He also notes that drunkenness became commonplace in the bunker as hope gave out. – Jojn Bergstrom, PopMatters

We are not living in the intensity of the Führerbunker, but there is despair in the air. A teenager I work with says that she feels as if her generation has been born into the ‘badlands’ of time. Suicide rates are high and climbing. Escapism into artificial realities, gaming and movies is common. Anti-depressants are increasingly prescribed, along with other medications. Hope is on the wane. It’s not surprising that many of us choose to revel in the physical comforts available to us. ‘Let’s forget about how bad things are, it’s too depressing. I don’t want to know about homelessness, plastic-bag islands, overloaded boats, drowning children. Let’s party! With whatever time we have left.’ I spoke with a man in his eighties who told me, ‘This place is fucked. I can’t wait to get out of it. You young ones can sort it out – I feel sorry for you.’

And this is an understandable response – to want to exit. But let’s look at another historical event, the sinking of the Titanic (one of my favourite childhood stories). This real-life tragedy reveals multiple human responses to a catastrophe that took those present quite by surprise. If we think of the human archetypes, to which do we relate the most? Would we humbly accept our culpability and go down with the ship, like its builder Mr Andrews? Shocked and stupefied, would we stand in position on the bridge like Captain Smith? Or are we one of those lucky ones in the lifeboat, feeling sorry for those who are drowning but refusing to jeopardise our safety by helping them? Are we heroic Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, the only person who went back to save those freezing in the water? Or are we musicians, playing calm and upbeat tunes on the deck, a small offering to ease the collective nerves in our final moments?

We may not have hit an iceberg, but our species is in dire straits. I often feel as if we are in a war, but with an enemy that is hard to identify. It’s a collective practice that many of us have chosen to follow, placing profit over planet, wilfully ignoring the results of our choices. Knowing that our actions are harmful: to the planet, to our employees, to our families. Choosing a mantra of individual choice rather than collective responsibility. If people are poor, it’s their own fault. If people accept low wages, it’s their own fault. If the government isn’t regulating our waste products, it’s their own fault. Battle lines are being drawn with increasing passion, even vehemence. We can feel it around the globe: situations are coming to a head. America’s new president is not just a joke – this is a scenario of real consequence. The political choices we make matter now more than ever – there is so much at stake. The TPP matters. The Paris climate deal really matters.

Knowing what we know, I think it’s irresponsible to fly to Australia to go shopping. When I see billboards advertising cheap fares to Melbourne for a shopping spree, I feel as if I am at war, or at least that I should be. When I witness a male team sport being placed on a pedestal high above other national accomplishments, when I note their pay packets compared with those of teachers, I feel as if I should be at war. When I see a pamphlet for liposuction or cosmetic plastic surgery, at enormous cost, I feel as if I should be at war. I reach into my pocket for my metaphorical grenade; but some of the people I am at war with are my friends, some are my family members – sometimes I am at war with myself. These are not merely individual choices, matters of personal ‘freedom’. These choices have an effect on the rest of the system. These are questions of resources, of values and of prioritisation.

We are all the inheritors of the culture, the social beliefs and the customs we were raised with. We are all perpetrators in some ways and victims in others. Some of us may be more responsible than others, and some of us may have been actively working to avoid this crisis. But whatever our stance, we are all bound together by a common threat: the health of our planet is at risk. And intrinsically connected to this are a host of vicious social problems.

It is deeply disturbing that people are once again being killed publicly for their sexuality. Likewise disturbing is that women and children, those people for whom we supposedly fought the ‘war-to-end-all-wars’, are still in dangerous, violent situations, that we live in a society that still normalises rape, domestic abuse and poverty. The broad catch-all term ‘inequality’ sums up the gross injustice of the way we hold some lives to be more important than others, allowing a small minority to live an exaggerated high-life while others struggle to survive.

I read with interest the text from a recent Canadian Munk Debate. The proposition was ‘Progress. Be it resolved, humankind’s best days lie ahead’. A panel of wealthy men discussed the topic. Citing statistics of improved health and poverty, the ‘for’ team assured us that ‘things are getting better’ and the ‘against’ team could not come up with convincing retaliations; 71 per cent of the audience agreed with the motion before the debate, and 73 per cent afterwards. But this skewed upper-class audience and these skewed upper-class debaters only tell a skewed part of the picture. I would like to see how the debate would change with some women on the panel. Or a broader cultural spread – anyone not from America or Europe. Or anyone not of these men’s age group. Or anyone not from their wealth bracket.

More than ever, we need feeling humans. Humans who can exercise their hearts as well as their brains.

We might see these thinkers as the height of our species, Homo sapiens, wise man. And perhaps that is the problem. Perhaps Wise Man’s time is over. Perhaps we should say, ‘Thank you, Wise Man, you have done well, we are very grateful for all you have offered, but now there are other aspects of our humanity that we need to focus on.’ More than ever, we need feeling humans. Humans who can exercise their hearts as well as their brains.

The students I teach at university don’t have a problem with knowledge. Knowledge is freely available these days; we can google almost anything. The crisis is around agency and action. Feeling confident enough to speak out, to speak up, about the changes you want to see in the world. To back your intuitions. Knowing what stories to tell that will shift people’s consciousness.

The recent World War I commemorations in this country have not offered any opportunities to reflect on the choices we make and the values we hold as a nation. There are major questions up for grabs about how we want to live as a species. Is ‘survival of the fittest’ the best rule we have? I’m looking for the next evolution of our race. Will it be Homo economicus – Rational, Financial Man: he would be very good with spreadsheets. Or Homo artificialis veritas – Artificial Reality Man – he comes with a built-in virtual-reality headset. Personally, I hope that our next human iteration will have increased empathy. Increased sensitivity. Perhaps an upgrade around listening. Homo compatiens: compassionate humans. That’s what I am hoping for.

I imagine that this new evolution would try to improve the situations that we have made for ourselves. Rather than advancing ever forward, progressing, always creating new realities (whether on Mars or in virtual worlds), these humans would instead deal with the crisis we are currently in, right now, all around us. They would attend to the damage we have caused to our planet, they would take responsibility for the ongoing wake of colonisation and use these great big sapiens brains that differentiate us from other animals to find some inspirational collective solutions.

And this kind of radical approach is starting to happen more and more. Many New Zealanders are putting their energy into their own neighbourhoods — making sandwiches for their schoolchildren, cleaning up their rivers, finding warm and secure homes for those most vulnerable. They act regardless of the government’s initiatives: they see a direct need and respond to it. They belong to churches, gangs, iwi, art collectives, community groups. Some are social enterprises. Some are businesses. Some are children.

But others of us tend to stay on our safe lifeboats. We find it hard to see the systemic privilege that keeps some of us at the top and some at the bottom. ‘I am sure those families could survive on their WINZ benefit. Spongers. It’s their own fault. I’ve worked hard . . .’ Et cetera. And these careless attitudes can lead to volatile situations. We in Aotearoa are not at the extremes of polarisation that we see in America and the UK. But we could go that way, if we let ourselves.

It’s likely that deaths from extreme weather will continue and increase. Thanks to North Korea, nuclear attack is on the cards again; maybe it was never off. Times are tough now, and they will get much tougher before they get easier again. It’s possible that humans as a species will not survive. I hope that we will. But we may not. And so this time, when the pressure is on us, when we can feel the great curtains twitching as if they might be about to close, is a time when we could choose to make some heroic choices. Or not.

I can look again at images of Pompeii and of Lajia, skeletons clutching loved ones, and it isn’t terrifying to me anymore. They were together, in the final moments.

When we can feel a possible ending, a possible death, we can use it as a moment to focus on what is important to us in life. We could hold out for some radical, social vision right now, one that cares for all members equally and refuses to prioritise the wealthy over the poor, the powerful over the powerless. Or we could just focus on ensuring that we are in the elite, upper-class oligarchy, among those who will survive. We could make sure that we are first on the list for the new Google-funded innovations promising life extension through cryogenics and organ replacement. Or we could invest and take care of the lives that are here now, the hearts that are beating now, the human spirits that are already in existence.

Ironically, once I accepted the possible demise of humanity, it liberated me to act with more courage against this occurrence. Now that I am fairly sure that disasters, both natural (tsunami, floods, drought) and human-made (war, sex trafficking, nuclear attacks) will take out a significant number of our race, and I have grieved for that, what concerns me is how to preserve our rich cultures and what will aid us in basic survival.

I want my children to know how to plant and grow their own food, how to erect shelter for themselves. How to keep healthy. How to assist those in birth and old age. How to pass on what they know to their young ones. How to resolve conflict. How to welcome newcomers. How to dance. How to sing. How to celebrate and enjoy the moments they have together.

When I think about it like that, I can look again at images of Pompeii and of Lajia, skeletons clutching loved ones, and it isn’t terrifying to me anymore. They were together, in the final moments. They weren’t filling out a customer satisfaction survey, or stuck in traffic trying to get home to the babysitter. They weren’t on hold listening to Dave Dobbyn, waiting to speak to a live person. Rather than seeing what was ripped away, I now see what was held in that moment. It makes me feel grateful for the life that we have, whatever length it ends up being, whichever way it ends.

And every day I imagine that this day could be my last, and imagine how I would feel if this were the last time I ever saw the people I am with. This makes me act more carefully, and more freely. Death and life rely on each other for existence, so when I think about how I want to die, I am really asking myself how I want to live. And if I end up on a lifeboat, I hope that I will be brave enough to play the role of the fifth officer, to turn the lifeboat around and go back to help those who are struggling. And if I end up on the giant ship, going inescapably down, and I find that there is an instrument within reach, I will do my best to make the richest and most honest musical sounds that I can make in whatever moments I have left.

The Journal of Urgent Writing is available from Massey University Press.