From Dwelling to Destination: On New Zealand’s House Museums

Sebastian Clarke on the character and reputation of our most idiosyncratic institutions.

Sebastian Clarke on the character and reputation of our most idiosyncratic institutions.

I will eschew any suspense and begin with an admission: I’m a hound for house museums. I seek out these introspective havens peppered throughout Aotearoa with great fervour. My self-appointed role as loyal advocate for our house museums emerged not by epiphany, but thanks to a scratchy, woven basket. Said basket resides in Nelson’s Isel House, a dollhouse of a building that greets visitors with a full face of hand-shaped local boulders sweetly framed by slim, red bricks. It may be the most unremarkable item in a house abounding in extravagant furniture and Sèvres porcelain, but from its upstairs station, this basket looks out to the parkland that embraces Isel House. Wood splints are collected from the park, planted by the house’s first resident, to make baskets like the one that refuses to be erased from my memory. This basket glows with a fiercely local provenance, and reminds me that experiencing interior spaces and objects so soaked in history is like time-travel – magic. However, as I encounter more of these memory palaces, buildings so rapt with the past, I cannot help but wonder about their precarious future.

The straightforward term ‘house museum’ describes, in correct order, a transformation from dwelling to destination. A trigger for us to reread the rooms. But the ability to generalise these places is much less straightforward, for each has emerged as a museum for a different reason. Some, like Larnach Castle, primarily for their exceptional architecture, others as havens for the decorative arts. Many house museums emphasise the story of a particular resident family, or construct a narrative emblematic of the history of one community. McNicol Homestead Museum comes to mind for its fastidious collecting of objects that together map out a story of settler life in the rural Auckland hamlet of Clevedon. Some house museums, while not architecturally significant, have been recognised as places worth preserving because of their notable residents. As our house museums go about their idiosyncratic missions, they all acknowledge a powerful heritage theory: that meaningful protection for a building means not only the persistence of their physical fabric, but also their place in the consciousness of a community that cares about their continued existence. Reflecting on the difficulty of holding on to our significant interior spaces (for heritage practices in Aotearoa are often only façade deep, privileging the retention of external building features) reminds us of the relatively radical presence of house museums. I could be at risk of placing too much expectation on these places, but I’m also aware that for some, our house museums are far from radical. New Zealand architecture and design historian Douglas Lloyd Jenkins has ventured that they are perhaps “...worthy rather than inspiring.”1 Jenkins’ declaration returns to haunt me on each new excursion to one of the growing number of heritage destinations open for visitation across the country. It is an assertion that makes me question whether our house museums are generating inspiration, or is inspiration a quality that they inherently do not possess? Could inspiration perhaps be channelled through intelligent and beautiful curation?

Beyond their sensory powers, house museums are also didactic, and through their physical fabric alone can communicate powerful historical realities

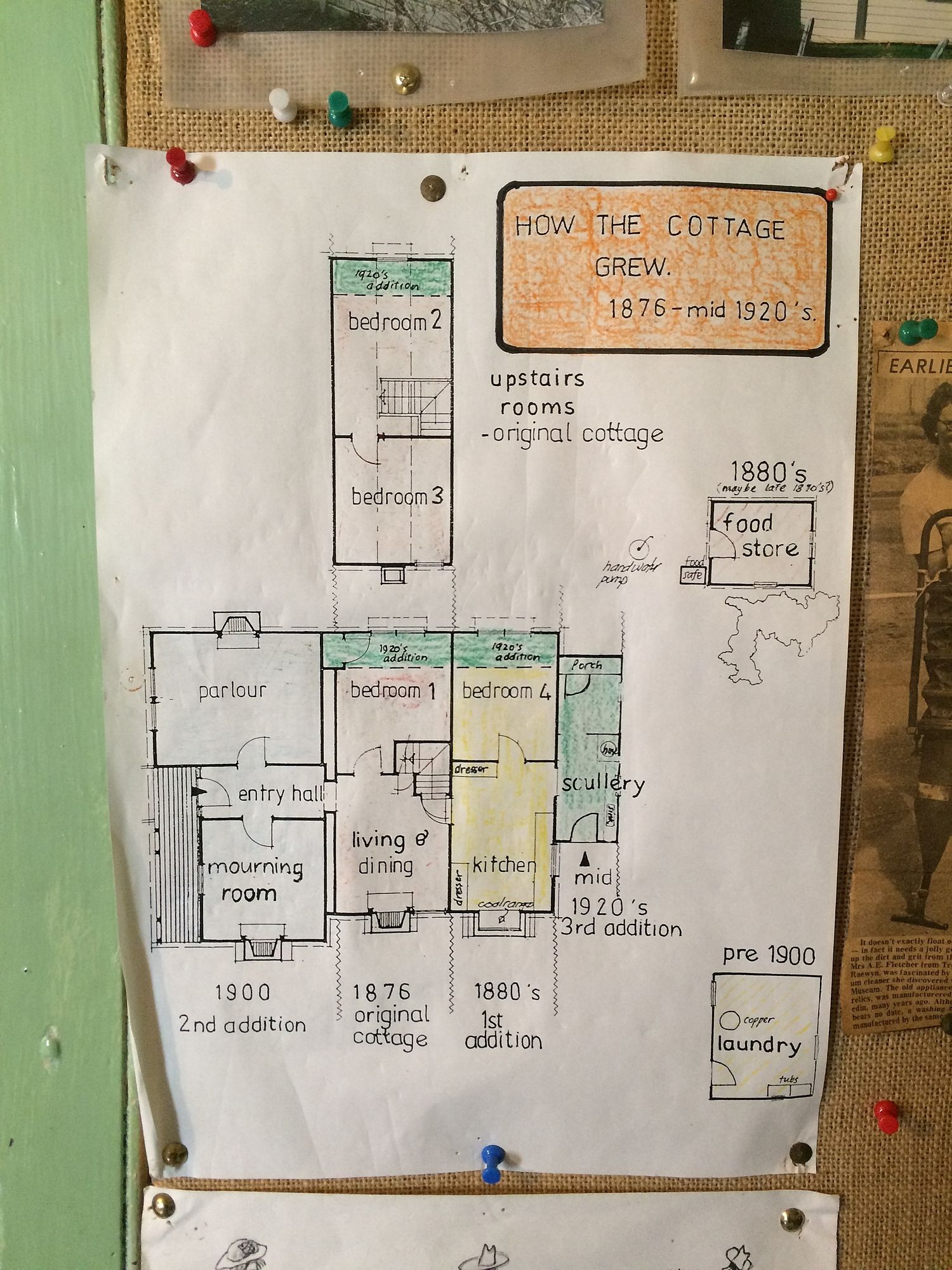

Experiencing New Zealand’s house museums has become something of a sport for me. Greedily, I want my surroundings to make me feel something. I know that hopefulness may be found within the frame of a window, that heartache can linger in the walls. Beyond their sensory powers, house museums are also didactic, and through their physical fabric alone can communicate powerful historical realities. In suburban Upper Hutt, Straven Cottage appears largely as it must have done when first constructed by John Golder in 1878. It was a humble home that was modestly extended over progressive decades up until the 1920s. Visiting the cottage today (it now operates as a house museum under the name Golder Cottage), it is not easy to detect, even from the interior, that there is a second storey where many of Golder’s 12 children had their sleeping quarters. The indiscernible presence of the upper level is intentional, its access found only behind what appears to be a wooden cupboard door. I climbed the narrow stairs behind the door, captivated with a heightened awareness of what this relic of New Zealand architecture reveals. For this furtive staircase illustrates how deeply fearful the early Pākehā settlers of Upper Hutt were, how their fear of a Māori uprising provoked them to design blockade-like domestic interiors. For students of history, experiencing firsthand the spatial design of places like Golder Cottage is a powerful means of understanding how real and pervasive the colonial disquiet was in the later part of nineteenth century. Memorably, the story of the hidden attic was recounted to me by a volunteer – rather than revealed via interpretive material. Perhaps this is a history the cottage prefers not to emphasise in its curation, allowing its wall texts (mostly handwritten on card and pinned to walls) to speak with more sentimentality about the Golder family.

House museums are more than their architecture. They are repositories of objects, which may act as agents for time travelling. Jorge Otero-Pailos explains that when we visit historic places “...we like to suspend disbelief in the same way as when we attend theatrical performances. We allow ourselves to think that we are witnessing the untainted evidence of the past when in fact it has been heavily manipulated…”2 What concerns me is that the curation of our house museums often appears as historical as the places themselves. Claimed as the oldest original settler dwelling in Wellington, the Nairn Street Cottage is an intriguing example of a house museum where the prevailing approach to curation has noticeably changed within the last decade. Previously branded as the ‘Colonial Cottage,’ rooms of the central Wellington home were once liberally furnished with all of the trappings of interior domestic life from the late 19th century – ersatz food scattered over the kitchen table was the ‘ideal diet’ for the resident mannequin, who held court in the living room, frozen in thought, making no progress on the embroidery on her lap. Today, the Nairn Street Cottage exhibits a refreshed commitment to its original inhabitants, the Wallis family. Rooms are now sparser, having been dispossessed of items not connected to the Wallises, which allows for a meditation on the family’s multi-generational occupation of the cottage – seen in the original, and now fragile, wallpaper; the patina of the well-trodden wooden floors; and the wooden cradle sitting beside the master bed. The purist in me finds the curatorial change commendable, but I can’t help but think others might miss the pot plants, mannequins, and layers of introduced rugs that contributed to the panoply – or pastiche – of history at the ‘Colonial Cottage.’

A beret resting on her bedside table, a theatrical mask hanging on her living-room door – her spirit seems to live in these moments

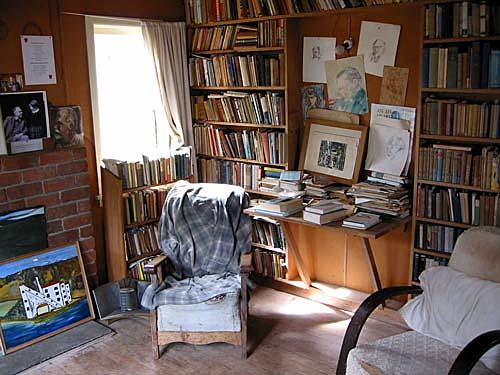

Approaches to the curation of house museums are as idiosyncratic as the stories they interpret. Elizabeth Aitken Rose’s examination of literary house museums in New Zealand reveals the varied approaches for presenting historically private places for public consumption. New Zealand currently claims four such literary destinations, focusing on the lives and legacies of Janet Frame, Katherine Mansfield, Ngaio Marsh and Frank Sargeson, and each of these houses enlists a distinctive strategy for conveying history through visitor experience. Where authenticity triumphs, as at Sargeson’s North Shore home, visitors get a faithful view into Frank’s austere living quarters – still filled with his papers, typewriter, and a well-worn patchwork quilt made by friend Janet Frame. With no velvet ropes limiting visitors’ access, Frank’s place still feels more house than museum – and its guardians are mindful of maintaining this ‘atmosphere.’ Meanwhile, the Katherine Mansfield House and Garden in Wellington takes a necessarily different approach. The house was extensively and expertly restored in the 1980s for the purposes of becoming a museum, but only a limited amount of material evidence remains to connect the museum to Mansfield and her family. Without an intact original interior and inherited collection, the Mansfield House has constructed an illusion of provenance, not dependent on the truth – an elegant patchwork of local history.

Taken one step further, the curation at both Ngaio Marsh’s Christchurch home and 56 Eden Street, Oamaru (the childhood home of Janet Frame) appears to favour mythologising tactics. At Marsh’s house, personal possessions have been intentionally arranged, probably by a former live-in curator (a position which no longer exists for the house), to create the impression that the writer may have left them there herself. A beret resting on her bedside table, a theatrical mask hanging on her living-room door – her spirit seems to live in these moments. Meanwhile, unlike most other house museums, Janet Frame’s house was established during her lifetime. Frame’s desire was for “an imagination that would inhabit a world of fact, descend like a shining light upon the ordinary life of Eden Street.”3 This inventive wish for the house, combining “facts and memories of facts” materialises as an interactive arena where visitors are encouraged to make their own meaning of the house through writing messages with Frame’s typewriter and through uncovering her quotations and poetry displayed in unexpected locations throughout 56 Eden Street.

To be frozen in time is a curious fate for any place

On my house-museum adventures, I’ve encountered a wide variety of curatorial approaches. However, most share a common quality: as consequence of their adherence to memory, they are overwhelmingly static. To be frozen in time is a curious fate for any place. Writer Ashleigh Young, who once worked at the Katherine Mansfield House and Garden, recounts “a space between exhilaration…and a deep stagnation that you could feel.”4 Perhaps it is the expectation of exhilaration that attracts people to visit house museums, while the stagnation does nothing to incite them to return. For while they are dependent on visitors for their viability, many house museums muster only modest attendance, most of which is made up of visitors old enough to recall the moment of transformation when house became museum. I am worried that stewardship of these places is quietly dwindling. What’s more is that many house museums are run by passionate, ageing volunteers, who have long-standing, or seemingly nostalgic connections to the stories of their house museums, connections which are inaccessible to new visitors. But as the passage of time moves us further and further away from the histories our house museums uphold, the critical question we need to ask is how do we ensure their stories are not forgotten?

On a global scale, there is pressing scrutiny on monuments that commemorate colonial histories. Duly, our own critical national discussions about the public legacies of Pākehā settlers urge us to look locally at our historic places to understand whose stories are being told, and whose are not. Many New Zealand house museums are devoted to colonial stories, often told with uncomplicated romanticism. Should we be actively seeking different voices to reinterpret these places, with a criticality and consciousness? After all, reinterpretation is in itself a heritage practice. New Zealand architectural historian and theorist Sarah Treadwell discusses, through her research of the historic Rangiātea Church, the ways in which the building has been reinvented, or “performed through transmitted practices” of storytelling and artistic representation.5 Treadwell’s argument that the architecture of a place “is more than an experiential object to be individually apprehended” acknowledges how social and cultural reinvention and reinterpretation become a valid part of the experience and understanding of architecture – and I feel this is especially true for interiors, as compartments for living. A house museum is, of course, not a new concept. There is encouraging precedent for house museums to play host for more provocative, if only temporary, reinterpretations.

There is no time for dust to gather here

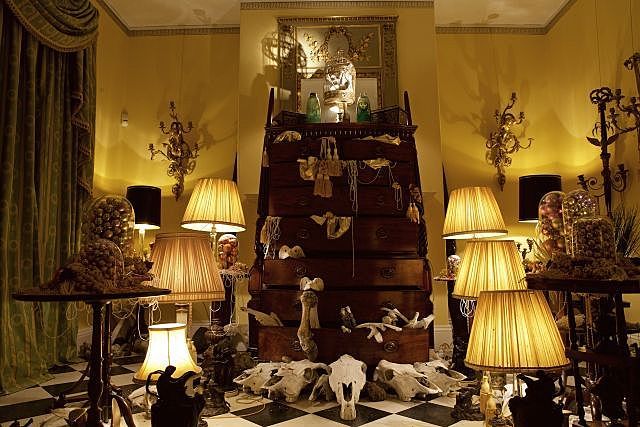

We don’t have to look far for ideas. The collection of antique dealer William Robert Johnston (1911-1986) in Melbourne is maintained and presented to the public in Johnston’s aptly named home, Fairhall. Here you will encounter one of the most active and sophisticated curatorial agendas of any house museum in Australasia. Annual programming comprises three seasons, beginning with a presentation of the permanent collection arranged by a guest curator. This is followed by an exhibition that introduces new objects, or ways of seeing, into Fairhall. Past exhibitions have been organised by the likes of fashion house, Romance Was Born, and artistic director of the Australian Ballet, David McAllister. These re-imaginings have expanded the possibilities and audiences of the Johnston Collection. Each year is concluded with a Christmas display for which the museum commissions a different community from across the state of Victoria to make new work for the collection inspired by Johnston’s life and legacy. What struck me as a visitor to the Johnston Collection is the value of its commitment to investigating – and encouraging diverse audiences to consider – how we collect, live with, understand and enjoy objects. There is no time for dust to gather here. To borrow Douglas Lloyd Jenkins’ descriptors, this endeavour feels both worthy and inspiring. The model of the Johnston Collection further fuels my interest in seeing house museums in Aotearoa deviate from the expected in favour of the daring.

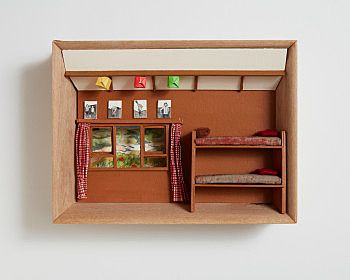

Despite the sense that many of our house museums are still some way from entertaining the idea of reinterpretation, what I find encouraging is the fruitful engagement of our visual artists with memory as tied to interiors and the objects that fill them. I can think of two recent examples. Earlier in 2018, Auckland-based artist Sarah Hillary presented a series of diorama for her exhibition Things to remember, shown at Anna Miles Gallery. The works depict the interiors of baches Hillary has known, places warm with the memory of family and friends. Completed with miniature fabric curtains, windows provide the dioramas with outlooks that proudly position themselves within the Aotearoa coastal landscape. By contrasting these natural scenes, finely and emotively painted in watercolour by Hillary, with the bach interior, we are reminded of our essential domestic needs: a bed, a bathroom, a place for food. Everything else we choose to bring inside, be it a painting, a book or a paper lantern, reveals something of who we are. Some of the places Hillary depicts no longer exist but they materialise once more through her creative practice.

In the 2017 survey exhibition Marie Shannon: Rooms found only in the home, toured by Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Marie Shannon’s long-standing interest in the domestic interior is demonstrated. In particular, with her 2016 text-based video work The Rooms in the House, Shannon considers the ability for one generation to derive meaning from the objects of their predecessors. After the birth of her son, Shannon notes that “...the things we thought in some way defined and presented our ideas and tastes...” would not be understood in this way by her child. It is a salient observation that highlights how our interiors are coded with cultural information. Shannon’s acts of recording and valuing our interiors help to ensure this information is not lost.

Recently, Dunedin-based musician Dudley Benson released a video for his cover of Shona Laing’s 1988 song (Glad I’m) Not a Kennedy, shot at Olveston Historic Home in Dunedin. Olveston’s lavish interiors played host to many cultural gatherings in the first half of the twentieth century. Entertaining was an integral part of this house’s story, and yet walking from room to room on a guided tour does not reveal that Olveston was once a place of community and excitement. Sometimes, reinterpretation is actually about evoking those histories through a totally different medium. In Benson’s video, moodily shot in black in white, we see two bodies move in slow ecstasy within Olveston’s card room, an intimate environment draped in velvet and Middle Eastern textiles. It is easy to imagine memories having been made – and kept secret – here. Later, Benson and a small cast of performers are in Olveston’s Great Room enacting a ritual choreography, limbs, hair and veils in full flight. Olveston’s legacy as a cultural gathering place lives on.

Hillary, Shannon and Benson’s works all suggest that perhaps we are beginning to think about historical interior spaces through a contemporary lens, to explore how to make them relevant to a contemporary audience. This August will see another iteration of this desire to reinterpret, with the opening of The Rooms at The Elms Te Papa Tauranga. Organised in association with the Tauranga Art Gallery, The Rooms brings together artists Vita Cochran, Matthew McIntyre-Wilson, John Roy, Maureen Lander, Gavin Hurley, Crystal Chain Gang, and Emily Siddell and Stephen Bradbourne, who are each making work in response to a different room within the grounds of The Elms. The Elms is the site of centuries of human occupation. Located on a peninsula between the Ngaiterangi Pā settlements at Otumoetai and Maungatapu, the Church Missionary Society was invited to establish a mission station there in the 1830s. Decades later, the missionaries sold the station and it existed as a private residence for members of one extended family for more than a century. The mission house and library are now the oldest known surviving buildings in the Bay of Plenty region, and their contents include important local taonga and domestic craft made by previous residents. The lack of a civic museum in Tauranga makes the public accessibility of The Elms and its collection only more significant.

Here is an exhibition that will include contemporary Māori artists responding to colonial spaces, providing visitors with opportunities to appreciate a multitude of histories

The Rooms is therefore an event I find myself seriously excited for. Here is an exhibition that will include contemporary Māori artists responding to colonial spaces, providing visitors with opportunities to appreciate a multitude of histories. The Rooms also includes artists whose practices evidence keen sympathy with the collections of The Elms. I’m thinking in particular of Vita Cochran’s masterful embroidery, and how thrilling it is to imagine her work in dialogue with the historical textiles of the mission house – how it could assist in making the old new again.

Perhaps ‘making the old new again’ would be an elegant mission statement for all our house museums to take on. It’s a pursuit that embraces both the implicit worthiness and the inspiration that can be found in these places, and recognises that through processes of reinterpretation, we need never stop reading the rooms – and we refuse to let the dust settle. There’s magic to be found in these chambers of history, when we choose to be part of their futures.

1. Douglas Lloyd Jenkins, “Shady Past,” in Home New Zealand (December 2016/January 2017), 77.

2. Jorge Otero-Pailos, “On Self-effacement: The Aesthetics of Preservation,” in Place and Displacement: Exhibiting architecture (Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2014), 231.

3. Janet Frame, An Autobiography (Auckland: Random Century, 1989), 101.

4. Ashleigh Young, “Katherine Would Approve,” in Can You Tolerate This? (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2016), 108.

5. Sarah Treadwell, Rangiatea Revisited (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2008).