Hōri from the Bush

After returning to the workshop of his teacher and mentor, Robert Jahnke, Isiaha Barlow is drawn back into the world of Toi Māori.

I grew up on a pā in the backblocks of Waimarino National Park. I’m a country boy at heart, a hōri who dropped out at the age of 15. I failed School C because I was playing Spacies with my mates and missed the exams. I discovered I had a talent for drawing – my mates would constantly ask me to draw pictures for them on the inside covers of their school books.

After dropping out of high school I got a job on a farm and quickly realised the real world sucked worse than school. I knew I needed to upskill if I was to make a life for myself. Almost a year working on the farm and I get a call from my mother who tells me about an art course at the Whanganui Regional Community Polytechnic. The next day I pack my clothes into a pillowcase, say goodbye to my nan and koro and hitchhike to Whanganui to live with my aunt and uncle over the summer. While there I cobble together a portfolio of drawings, apply to the course and get accepted onto the foundation arts programme for the 1995 intake.

Two years later, I enrolled in Toioho ki Āpiti Bachelor of Māori Visual Arts, a flagship programme designed by Robert Jahnke. This uniquely visionary school at Massey University produces some of our highest calibre Māori artists, curators and intellectuals. Today at Toioho ki Āpiti Kura Te Waru Rewiri is at the helm, a tohunga with tremendous knowledge. Her continued advocacy for Toi Māori will see future generations of artists emerge as both great practitioners and ambassadors for the movement.

I left the art world in 2006 to pursue a career in the tech industry, an opportunity that was made possible because of the self-confidence instilled in me from growing up on a pā and the skills that I acquired from Toioho ki Āpiti. Then in December 2020 and Aaron Lister from City Gallery Wellington gets in contact with me. He’s interested in showing artworks from my Saints series in an exhibition called Every Artist. I offer to submit 12 unseen paintings from 2006 that have been lying hidden in a cupboard gathering dust. However, before sending them I need them to be framed, and the framers are in Palmerston North.

Kia ora, is Mr Robert Jahnke around?

I take the day off work in February 2021 to visit the framers and to pay a quick visit to Robert Jahnke. It's been 15 years since we last spoke, and I’m excited to catch up over a cup of tea and biscuits. I’m anticipating a quick harirū, one hour tops, to find out the latest gossip in the Māori art world then make my way home. I pull into Te Pūtahi-a-Toi car park and I’m filled with a sense of peace – I’m home. I reminisce about my student days at the school. I have many fond memories here, it seems like a lifetime ago.

I make my way to Bob’s office, but can’t find his name on the door – instead, it reads ‘Mason Durie’. I’m flooded with memories of attending Mason’s classes, an absolutely brilliant Māori academic, very distinguished, softly spoken, with a sharp wit and great sense of humor. He had Victorian-era mannerisms, the kind of posh Māori who garnered respect from both rangatira and ringawera.

I peek into an open door, “Kia ora, is Mr Robert Jahnke around?” “Bob’s here somewhere,” the staff member replies, “I think he’s in the workshop.” I’m led downstairs and hear a distinctive laugh, it’s Bob. In the workshop, Bob and a technician are holding a large black object, it looks extremely heavy. Bob is at the end lowering the slab onto its side and he turns to me and says, “Grab the other end.”

This man hasn’t missed a step, sharp as a tack, maybe a little deaf in one ear, but still the same Bob I remember. We spend the next two hours packing and moving his artworks, all the while trading jabs, quips and barbed remarks between moments of laboured breathing and heavy lifting. It's hard work, the day is only getting hotter, but the good company seems to make the job lighter. It reminds me of standing over the hāngi pit at the marae with whānau you haven’t seen in years, picking up where you left off, reconnecting while trash-talking and joking around.

The āhua of these artworks is unnerving and breathtaking

Bob explains his construction methods, he shows me the microchip insert that he uses to program the circuit sequences for his neon lights, and speaks about his frustrations with the new computer he has. We pause and marvel at the technician’s freight boxes. They are well constructed and engineered to provide a secure enclosure for transportation of the works to the Auckland Art Fair.

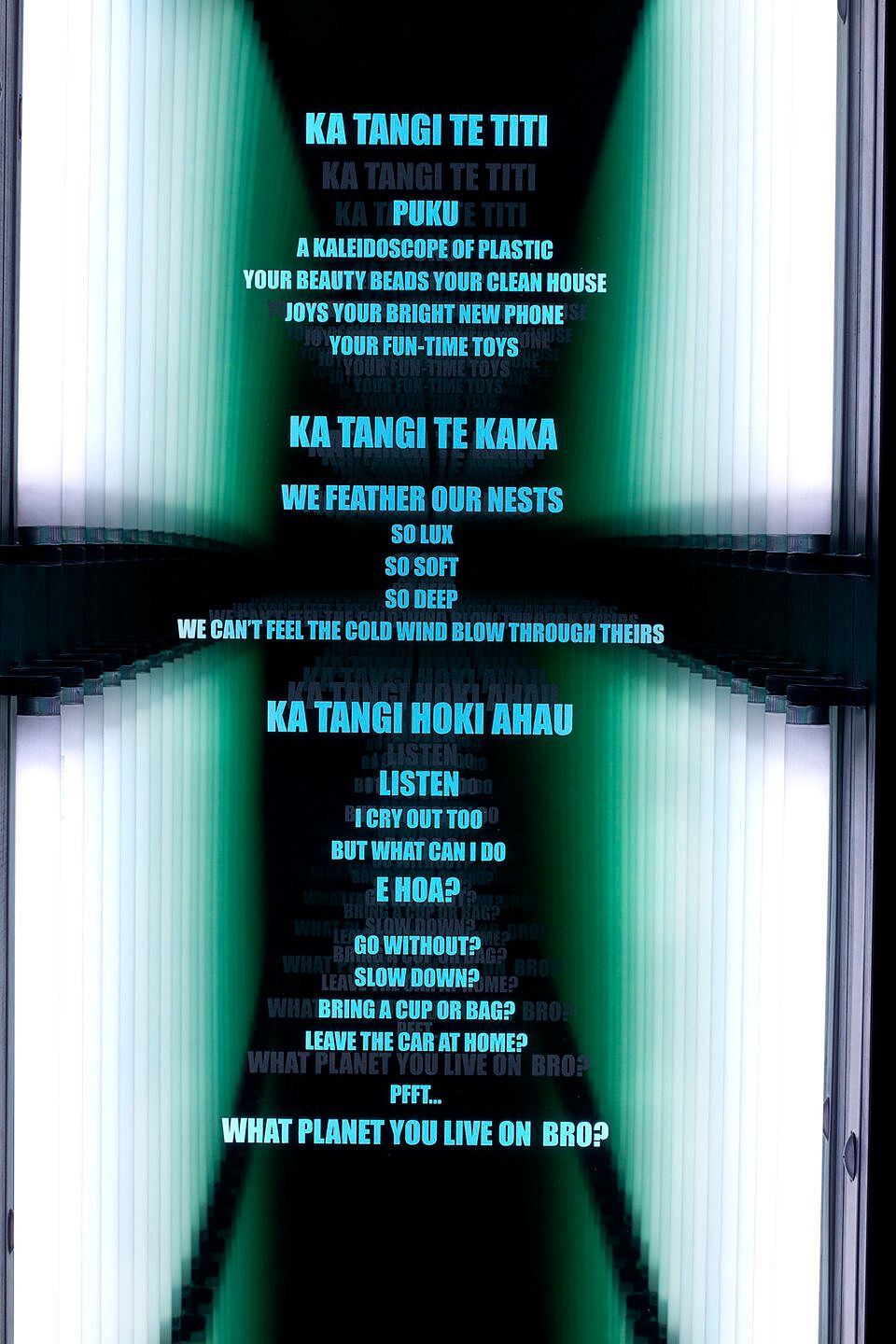

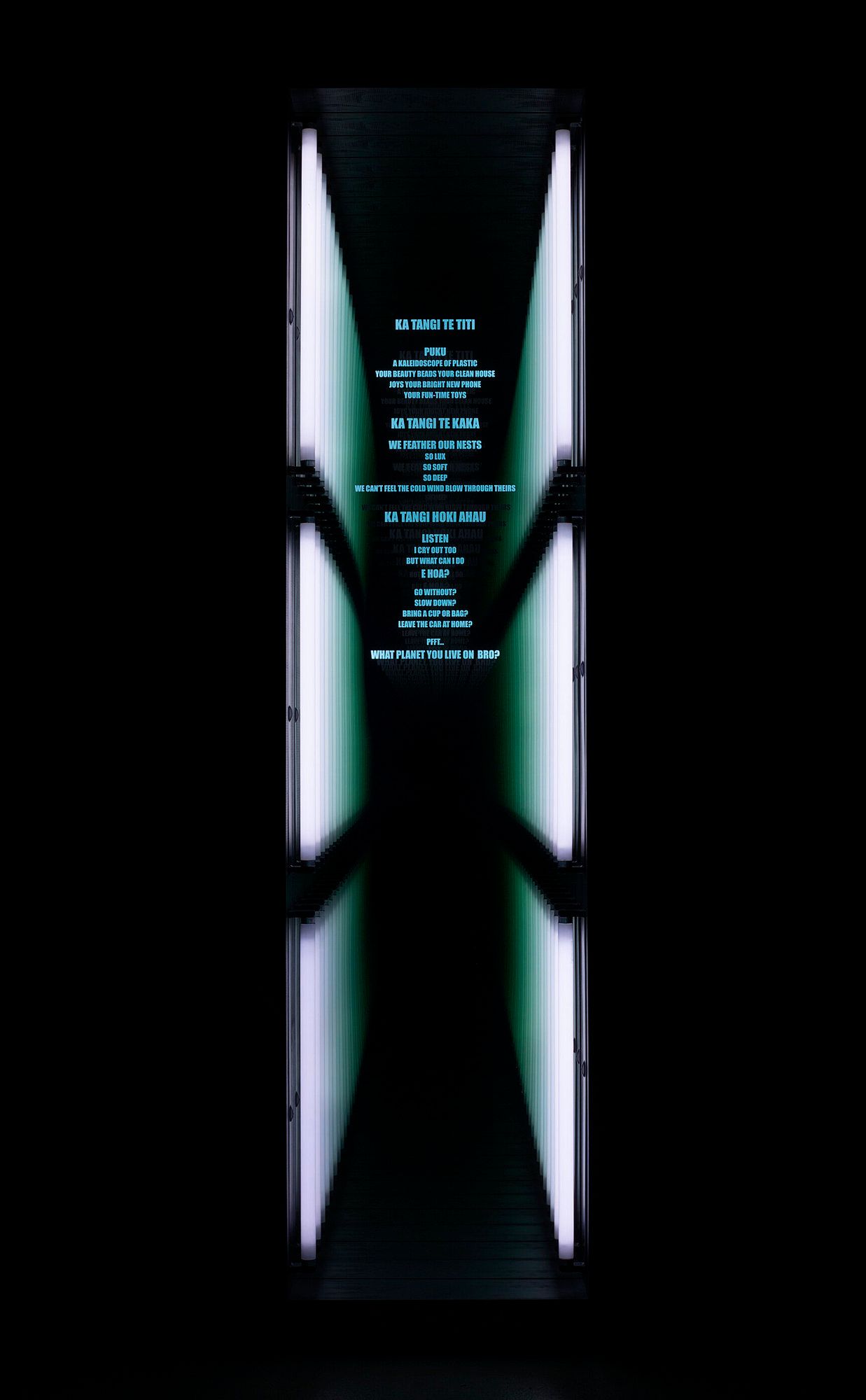

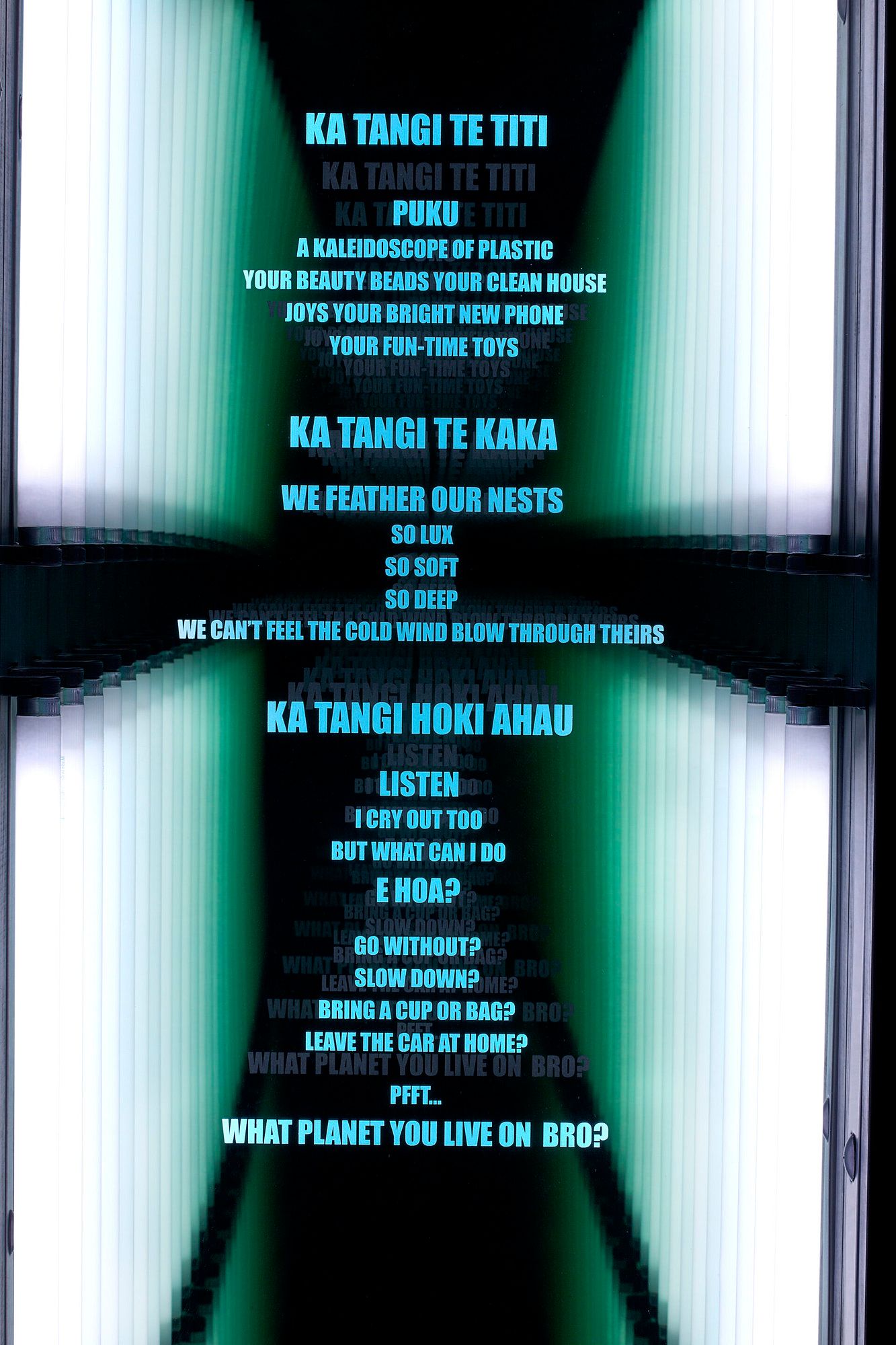

These artworks are colossal constructions, five in total. Each one reminds me of the black monolith from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. They are imposing in size and impressive in complexity. The simple outer frame and casing masks the very intricate maze of electrical engineering going on behind the scenes. This series of works is connected to a programmed circuit that animates the neon lights mounted inside the mirrored glass channels.

We pack the final artwork away and move it to be loaded onto the trailer. I’m then introduced to another series of three artworks occupying the student lounge. This time Bob plugs in one of the artworks, and I get to see it in action. As Bob switches the artwork on, the kupu changes color, turning a ghostly white hue and, in an instant, the artwork awakens. The kupu flows outward into the abyss. It’s as if a portal back to our ancestors has been opened and a dialogue invoked. The āhua of these artworks is both unnerving and simply breathtaking.

I move around the object, peering into the darkness trying to get a sense of distance. The kupu echos into the void creating a sense of movement while simultaneously being suspended in space and time. My eyes and brain comprehend the mechanics of this optical illusion, but the feeling of an immediate connection to my ancestors is palpable. For some reason, images of photographs at the end wall of a wharenui pop into my head. The colour of the kupu turns a green hue as they fade into the distance.

The awesome power, mana, mauri and wairua pulsating from these taonga is profound

Robert Jahnke, Lamentation III, 2019. Wood, paint, one-way glass, mirror, fluorescents, electricity. Image courtesy of Norm Heke. Poem by Tina Makereti, 'Titi Treaty'.

Robert Jahnke, Lamentation III, 2019.

The green hue of the kupu is the same color as the patina found in faded photographs of tūpuna on the back wall of almost any wharenui. It’s an eerie sensation. My mind quickly turns to a memory of being in the basement of the Whanganui Museum surrounded by taonga Māori, enveloped by the power and mana of the artefacts of my tūpuna. These taonga of Bob’s are something to behold! They are beyond words.

I make a barbed remark, “You're too smart for your own good.” Bob laughs. My veiled comment hides my inner thoughts, it’s a defensive mechanism that camouflages my true feelings. I don’t want Bob to know that I’m impressed and a little freaked out by his work. I know he can see right through my façade.

Contemporary Māori artists like Jahnke have often married Western art conventions and Māori culture together by using a combination of kupu Māori, customary patterns or references to tūpuna within their art practice. This convention of combining Māori and non-Māori artistic and cultural traditions has enabled contemporary Māori artists to speak to both a Māori audience and a non-Māori audience in very different ways.

There is a careful balancing act negotiating between these two cultural traditions and Jahnke has often spent his career at the edge, pushing and teasing the boundaries of this thing we call contemporary Māori art. His work demonstrates a high level of aesthetic sophistication and, like other notable artists such as Micheal Parekōwhai, Lisa Reihana and Brett Graham, he stretches the limits and our perceptions of what Māori art is – and, more importantly, what Māori art can be.

Jahnke is able to cleverly converse with a non-Māori audience and, at the same time, kōrero in a way that only Māori would understand. His works are not smart and clever for the sake of being smart and clever, they are deliberate, concise and to the point. While we can appreciate Jahnke’s neon reflections in aesthetic or intellectual terms, it is the way they essentially talk to his Māori audience through the wairua that elevates these artworks to another plane.

As quickly as I am transported into another realm and communicating with my tūpuna, I am brought back to reality

I am perplexed at my initial reaction, because this series of artworks provokes in me the same response as if I were standing in front of a carved pou tokomanawa. It is unbelievable and shocking. I never would have anticipated the physical reaction I experience while standing in front of Jahnke’s work. I am careful not to stand directly in front of these portals for fear of my soul getting sucked into the void. I have to quell the superstitions in my mind, it is completely silly and ridiculous! Yet the awesome power, mana, mauri and wairua pulsating from these taonga is profound.

As quickly as I am transported into another realm and communicating with my tūpuna, I am brought back to reality. These artworks need to be ready to transport and daylight is burning. After packing the artworks into the crates Bob suggests, “Let’s go to lunch.”

We hop into Bob’s truck and drive into town. I realise I had not transferred money into my account the night before, I know at least $20 is available but my phone is flat so I can’t transfer more. Too proud to ask Bob to stop at an ATM so I can check my financial situation, I sit there like a caged bird. We make idle chit-chat – all the while I think to myself, I’ll just grab a burger and coffee, anything under 20 bucks and I’ll be sweet as.

We get to the café, Bob orders his kai and I ask for a burger. “We don’t do burgers,”the host replies. Before I can say, anything Bob orders me a steak. I look at the price, it's 30 fucking bucks! I laugh in my head about the prospect of my bank card being declined when I go to pay for my kai. We order drinks, I order a beer. Fuck it, a little alcohol will blunt the pain of the embarrassment that is sure to come when I attempt to pay for this $30 steak. We find a seat near the entrance and sit down at our table.

Don’t act like a hōri, I remind myself

There’s a change of direction in the conversation as I begin to talk shop. I’m interested in finding out what's been happening in the Māori art world. I’ve been away for 15 years. I’m impetuous, asking rapid-fire questions, trying to get a sense of the landscape and absorb as much information as I can. Like a wise old sage, Bob answers what he can in a deliberate and thoughtful manner.

Our drinks arrive. Our host is a young Pākehā woman, mid-20s, very polite, she has a kind face. She pours my beer into a stemmed glass, I just about ask for the bottle but remember I’m out in public. Don’t act like a hōri,I remind myself. Our kai arrives shortly after – I look at my plate and there’s a steak the size of a 50-cent coin. I fight back my impulse to laugh, because that’s not enough protein to fuel my Polynesian frame for five minutes. Bob did warn me that the steak was not that big – “not that big” in my mind is a steak the size of my palm.

We finish our kai and it's time to pay the tab, but before I can stand Bob is making his way to the counter. Unsure of the social etiquette, because I never go out to fancy cafés, do I offer to pay and embarrass myself when my card gets declined? I make my way to the counter, pretending to reach for my wallet. The host tallies the total cost of lunch then looks directly at me and asks,“Soo... How are we paying today?”Hand still in my back pocket, and an “Oh fuck!” look on my face, Bob whips out his wallet and exclaims, “I’ve got this... I’ll pay for the lot!”My heart rate drops as Bob picks up the tab and I’m able to maintain a small amount of dignity – I thank Bob for lunch then we head back to school.

We arrive back, hitch the trailer to Bob’s truck and reverse toward the freight boxes. Bob claims to have calculated the best way to lift these massive artworks onto the trailer. I suspect he figured it out over lunch. His plan requires an elaborate sequence of manoeuvres. Talking quickly gives way to laboured grunting as we spend the next few hours heaving these monolithic slabs about. We both jokingly remark, “No need to go to the gym today.”

I will leave that in the hands of the Māori art gods

We drop the artworks off at Bob’s home studio, return to load the remaining works and push the trailer load of artworks into the studio workshop. Done for the day, we exchange a hongi, some salutations, then part ways.

Going back to Toioho ki Āpiti reminded me of going home to my papakāinga – if you've grown up on a marae, you know how the story goes. There is always work to be done, heavy lifting and holes to dig. Those of us who leave and then eventually return, often with our hat in hand, are humbly reminded about our place in the wider scheme of things.

Perhaps it's just me that feels this way, but even when I left the Māori art world in 2006, I always felt that I had an obligation to return and contribute to the greater cause. It’s an odd sensation and I wonder if Pākehā artists feel this obligation in their art practice, or if this is a distinctly Māori thing.

In the case of Toioho ki Āpiti, this is my turangawaewae outside my own papakāinga. My artistic roots are here, and the pull back into the fold that is the Māori art movement is strong. As to the capacity or role that I will find myself in, I will leave that in the hands of the Māori art gods. Whatever the case, while there is still some heavy lifting and work to be done, I’ve got my work boots ready.

Feature image credit: Harry Curly