Hidden Women

Sarah Jane Barnett on the complexities and intricacies across the spectrum of womanhood.

Sarah Jane Barnett on the complexities and intricacies across the spectrum of womanhood.

“I entered adulthood as two people: the image my era wanted me to be, and the other woman, the hidden one, the one with a body.” – Eve Fairbanks

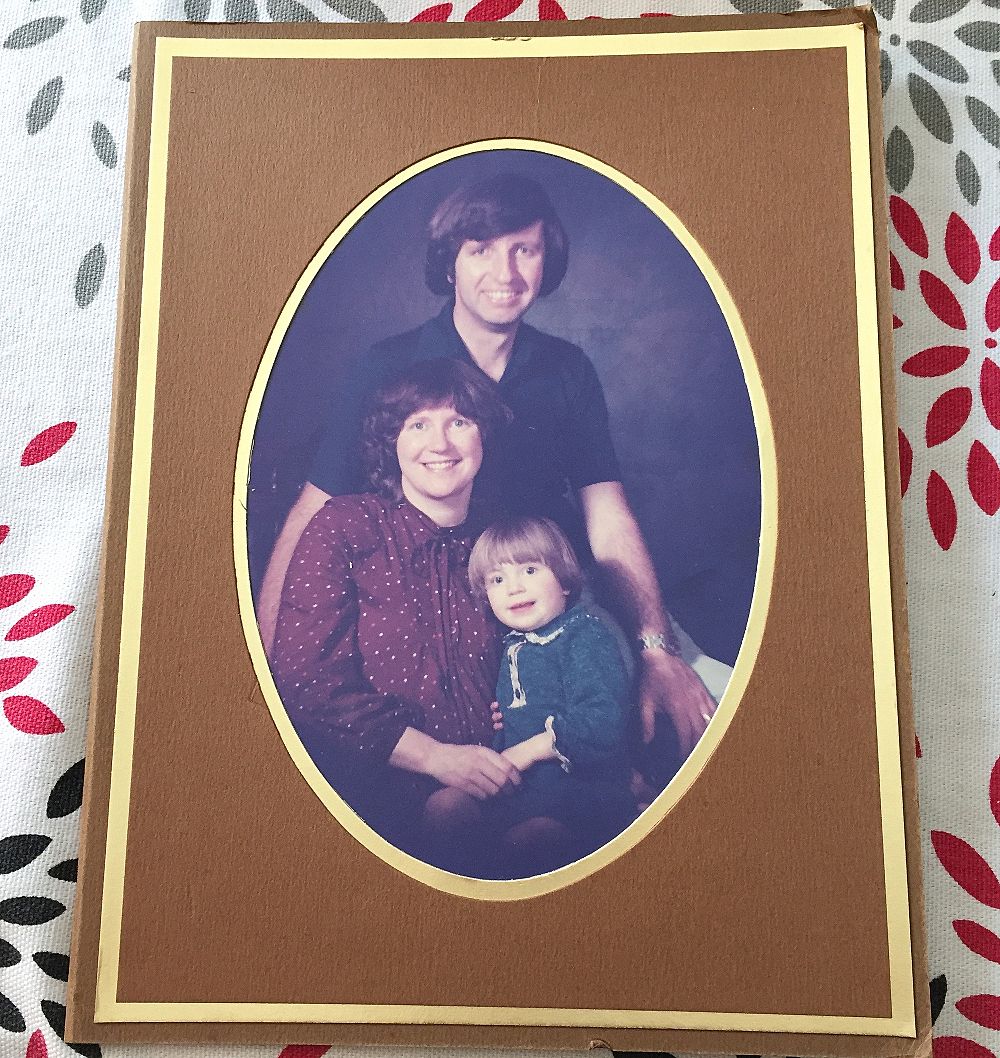

My mother used to wear a purple suit. It had a single button on the boxy jacket and it pulled in at her waist. The skirt was tight and smooth. My mother’s friends – we’d bump into them at the local mall, or in the aisles of the supermarket, my sister and I hanging off her arm – would come up to my mother, and after making polite conversation, say, “You look so good, Pauline.” They’d stand back a bit, cast an eye over the suit, and say, “Have you lost some weight?”

My mother’s a renowned public health academic, and has always been an outspoken feminist. I remember one time during high school when she pulled over and ordered my friend out of our car after he made a sexist remark. After I was born my mother could only take three months off work, so she would bath and feed me in the morning, go to work, come home again to feed me at lunchtime, before then going back to work. When my sister and I were at school, my mother worked for the Otago Medical School during the day while writing her PhD at night.

One school holidays, all of us crammed into a motel room in a South Island town, my father told my mother that she was too fat for him to love her anymore. I remember spittle at the corner of my father’s mouth, and the anguish on my mother’s face. I remember not being able to sleep that night, my sad little body deep in the bed.

Those motels always had a pool that the kids – whom my sister and I took as our immediate best friends – would splash in and out of all day. There’d be a rusted swing set and a television room where the adults could drink. These holidays were the best my parents could do at the time. They were good people in a hard situation, and one I couldn’t understand as a kid. What I did understand was that a few months after the holiday my mother had lost weight and bought a purple suit. That people liked her better that way. That she was better.

I’ve been thinking about womanhood – of what it means to me, and of what I’ve been taught – because I’ve just had a hysterectomy. My gynaecologist gave me the news as we sat in his office, light streaming in through the large windows. The air punched into my chest as he told me I needed to have my uterus and fallopian tubes removed. He was wearing a dark grey suit with a white shirt, his jacket casually unbuttoned.

At the end of the appointment he printed out a stack of medical literature for me to read. “These are written for doctors, so let me know if you have trouble,” he said. He leaned forward and said, “Don’t worry, the operation won’t make you less of a woman.”

There is literally no wrong way to be a woman. There is literally no wrong way to have a body

Most women will recognise this moment – a man who wants to be kind but who has few narratives to work with: the male saviour; the expert. This man does not do well when confronted with a self-possessed woman. Sitting in his office I reassured him that I was more than competent to read the literature, and that I was fully aware of what made up womanhood. He looked confused and laughed a little. Then he continued to reassure me.

Body activist, Chidera Eggerue writes, “There is literally no wrong way to be a woman. There is literally no wrong way to have a body as long as your body is functioning well enough to keep you alive.” As a child, I was always the first to dive into a cold swimming pool, the water a shock on my skin. I’d hold my breath, swim down and place my toes on the concrete bottom, my body pure joy in the silence. That day, I wish I’d told my gynaecologist that to school me on womanhood was to take something that was not his. I wish I’d climbed into bed with my mother that night and told her she was loved.

*

A month after I saw my gynaecologist, my husband dropped me at a Wellington hospital. A nurse took me to my room. A single bed and a comfortable armchair. Fluorescent lighting and plain walls. She bustled around as I stripped behind a curtain and pulled on a blue hospital gown. She took a urine sample, gave me the dinner menu, and left me sitting on the bed.

I’d brought with me The Tomboy Survival Guide by Ivan Coyote, a collection of short stories about Coyote growing up butch in Canada in the 1970s. The first story, ‘Not My Son,’ is about Coyote being mistaken for a boy as a child, and his mother’s reaction. Coyote starts to intentionally pass as a boy, and is quick to say, “I didn’t not want to be a girl because I had been told that they were weaker or somehow lesser than boys…I just always knew that I wasn’t.”

If anything, the women in Coyote’s family were seen as stronger than the men, and “handled most of the practical details of everyday life.” That echoes my experience growing up in the 80s and 90s; women were in charge of the household, the children, the finances and the social relationships. The difference: women were now also working. The slogan for the early 90s was the well meaning, ‘Women can do anything,’ which my mother cheerfully repeated to me from our newly renovated kitchen, apron tied over her work clothes while she cooked the evening meal. My mother as worker ant – she carried giant leaves and twigs, 50 times her weight.

My mother as worker ant – she carried giant leaves and twigs, 50 times her weight

In Eve Fairbanks’ piece, ‘We believed we could remake ourselves any way we liked: how the 1990s shaped #MeToo,’ she says that to understand how women feel today is to understand "the 90s – a peculiar era, caught between the confidence that there had been fabulous progress in the relationship between the sexes, and the smouldering remnants of a past."

Fairbanks describes the intense pressure felt by women in the 90s, because suddenly everything was possible. She points to The PowerPuff Girls, Sweet Valley High and ‘fuck-me boots’ (mine were black leather and zipped up the side) as 90s narratives of female empowerment and ambition, but not without contradiction. Sweet Valley High’s twins, Jessica the manipulative, party girl, and Elizabeth the sensible and studious nerd, were a modern version of the Madonna-whore dichotomy. Or as Fairbanks says of Princess Diana, “[she] was applauded for rejecting her ugly prince. But she was also painted as reckless for getting killed with her playboy lover in a car chase with paparazzi.”

And let’s not forget the Spice Girls – the Madonna-whore stereotypes expanded into Baby, Sporty, Ginger, Posh and Scary: five personas that are equally as reductive while advertising themselves as ‘girl power.’ “To acknowledge how younger women have struggled,” Fairbanks goes on to say, “would entail a painful admission that the battles of previous generations may not have been won as decisively as they had hoped.”

I thought about this while reading Coyote in the hospital room. While the slogan my mother told me may have been, ‘Women can do anything,’ what I learned was, ‘Women must do everything.’ Feminist Jessica Eaton says, “For women to be valid, whole human beings in society – feminism has got to move beyond this notion that women are striving for what men already have.” The problem with the 90s was that women were not able to create something new: they were given some of what men had while being expected to continue the traditional work of women. The space had not yet opened – and still may not have – for women to rise from the ashes of their old selves. My mother’s cheerfulness at the time was actually hidden defiance. When I asked her about it years later, she said, “I wouldn’t let the bastards win.”

While the slogan my mother told me may have been, ‘Women can do anything,’ what I learned was, ‘Women must do everything’

Eventually the nurse came back – wheeled me down the corridor, lights flashing overhead, through swinging doors and into the operating room. As she put needle in my hand she cracked jokes. She told me two surgical instruments would be inserted into my abdomen, and my uterus, cervix and fallopian tubes freed and removed. She slipped a mask on my face, and soon I swam in that place of no thought. Parts of me I’ve never seen were taken away.

That term, “freed.” It sounds so positive, as if my uterus were a rescued animal being released back into its natural habitat. I imagine opening the cage and my uterus making a break for it – the scuttling and squishy noise it makes across the linoleum floor, and down the hospital corridor. When it reaches the hospital door it turns back to look at me. It’s a sentimental moment: we acknowledge all of the years we’ve spent together, and then it disappears out onto the street.

I woke in recovery with a nurse touching my head. I don’t remember much of that evening. At some point I ate dinner and talked to my husband on the phone. I know another nurse gave me pain relief in the middle of the night, her dark figure moving quietly around my room. I know that when my husband came to see me the next day I fell on him and cried in long heaving sobs. I’d been so brave. That’s what the women in my family do.

*

My surgeon visited me the morning after my surgery. “You look fine,” he said. The surgery had gone well and there hadn’t been any cancer visible in my uterus. My ovaries hadn’t needed to be removed, and I felt a wash of relief at not needing hormone therapy. He paused for a moment then said, “Your ovaries were beautiful. They winked at me.”

To be reduced this way – to the beautiful and the coy – is to be made palatable. It does not recognise the bloodiness or complexity of womanhood. In the days before surgery I spent time thanking my uterus for the work it had done. I cupped my hands on my lower stomach. “Thanks,” I said.

My thoughts turned to the time at high school when I dubbed my best friend Melissa home on my bike. We’d been hanging around outside the local swimming pool when her period started and she didn’t have a tampon. She sat balanced on my bike rack as I pedalled furiously along the leafy Christchurch streets, both of us laughing and yelling, but silently afraid she’d get blood on her uniform. I thought about the final days of pregnancy when I could feel my son move under my hands. How the decision to become a parent – a decision that is still seen as fundamental for women but not men – profoundly connects me to the experience of other women who have children, as much as it does to women who choose not to, and women who can’t.

*

The first few days after surgery my abdomen was still swollen with gas. There were three small incisions on my stomach, each covered with a star of plaster strips. I could only lie on my back, as lying on my side or stomach was still too painful. I swallowed painkillers, carefully tracking when I took them so that the relief overlapped. I pumped my feet and legs in the bed to prevent blood clots, and got up each hour to do laps of our lounge. One friend brought me cauliflower soup, another chocolate, and I reassured my parents over the phone, especially my father who might soon be having surgery as well.

I have only seen my father in a suit twice in my life, once at my sister’s wedding, and once at my own. It’s strange to see her wear it – my father came out as transgender in her sixties. She is usually dressed in pretty tops and slacks, and always with a full face of makeup. At my son’s birthday a few months ago the magician asked how my father was related to the family. I stepped forward and introduced her as my ‘parent,’ the best way I’ve found to acknowledge my father while respecting her gender identity. Without hesitation, the magician said, “Good to meet you love.”

It was confronting and painful to watch my father go through adolescence in her 60s

It was confronting and painful to watch my father go through adolescence in her 60s. She wore tight red PVC dresses and long platinum blonde wigs. She put photos of herself in lacy underwear online. I understand that many trans people who come out later in life have a second adolescence like this to explore their gender identity. To see how the way they feel on the inside can be expressed on the outside. To find the edges of themselves.

When I asked my father about first knowing she was trans, she said, “I was about eight years old and I liked putting on my mum's fur coat.” She would also read her mother’s magazines, which “were full of lovely-looking 1950s women.” My father grew up in Ravensbourne, a poor suburb in Dunedin, in the 1950s. Her own father was a butcher, and her mother a fiery woman who ruled their household. My father didn’t yet know what being transgender was. She didn’t know she was different.

When I asked my father why it took her so long to come out, she said, “The main things in my life back then were the pressures on me to do well at school from my mum. My dad, although a lovely kind person who worked hard to support us, was not the role model my mum wanted for me. I suppose what I am trying to say is that often your identity is subsumed under other pressures. I think that has been the pattern in my life.”

*

During my recovery I watched Nanette by comedian Hannah Gadsby, a deeply funny, political and heartbreaking account of Gadsby’s experience of being “not normal”; she is a woman and lesbian who experiences herself as being seen as “incorrectly female,” and who has been persecuted because of her otherness. With unflinching directness, Gadsby talks of being beaten by a man because she was a “lady faggot,” of being sexually abused as a child, and of being raped by two men in her 20s. And worse than these assaults? The shame and self-hatred she carries.

My father and I last argued about womanhood when she proudly showed me an airbrushed photo of herself. The blonde ingenue staring back at me had smooth skin and strawberry lips, her face cheeky and inviting. I was marking essays in the study, my hair dragged back in a pony-tail, wearing a baggy t-shirt and track pants. “Stop buying into this bullshit,” I said. I pointed out my greasy-haired, no-makeup appearance. “Am I less of a woman?” I asked. My father looked crestfallen. “But you’re always beautiful,” she said.

My father never got the chance to be a woman in her 20s – to party and wear short dresses

I know I have internalised my father’s ideas about womanhood, which are in turn systemic standards of gender, and I don’t think it’s a stretch to say a type of trauma. Social scientist Meera Atkinson writes about how trauma is “a transmittable encultured process.” Her research reveals that the patriarchy creates a structural force that is inherently traumatic, and passes that trauma to the next generation – what she calls the “traumarchy.” Atkinson goes on to say:

Wherever the noxious root of patriarchy has been planted and fertilised…unsustainable gardens of grandeur have grown on the blood and bone of subjugated women, children, slaves, invaded and colonised peoples, and nonhuman animals. In other words, conceiving of trauma as a structural force uncovers the way it informs racism, sexism, homophobia, colonialism.

In that moment, I wish I’d had more empathy for my father, but I felt possessive of womanhood. I felt that my father was getting it all wrong. But my father never got the chance to be a woman in her 20s – to party and wear short dresses, and sleep with strangers as I did. To feel erotic and feminine and powerful. She never had the chance to learn that those feelings have nothing to do with how you look. At 30 my father was still searching the library to find out what was different about her.

*

Late one evening, a week after surgery, I finally realised that my uterus was gone. A huge wave of panic swelled in my stomach as I realised I couldn’t get it back. Where was it? Was it in some biological waste disposal unit? I imagined my uterus scrabbling at the sides of a plastic bin in the dark.

The next day, at my request, my gynaecologist sent me a picture of my uterus taken by the technician during biopsy. In the photo my uterus looks like it’s dancing: blueish fallopian tubes undulate from the reddish mass of the womb. It stands propped up on the thick white plug of my cervix. I immediately loved this strange and beautiful animal. Even though it’s gone, it will always be part of the first 40 years of my womanhood, and I’m grateful. That afternoon I sent an email to update my father on my recovery. The subject line: “Today we are both women without a uterus.”

In the end, I lied when I told my gynaecologist that I knew what made up womanhood. ‘What does it mean to be a woman?’ is a flawed question. It presumes a single answer or experience, or that there should be one. My own identity includes both my mother’s and my father’s ideas of womanhood. I too did a PhD while working and raising a child. I too will not leave the house without first putting on makeup. Undoubtedly there have been other influences: celebrities, authors, friends and partners, high school bullies.

In her essay ‘Mothers as Makers of Death,’ on the difficulty of being a mother and a writer, Claudia Dey says, “To write is to be in conversation with yourself, to preserve a state of being so you can conclude a sequence of thinking and feeling.” This essay is one attempt at a conversation with myself, and it’s a conversation that will be ongoing.

Women, throughout our lives, and as society pushes forward, will have to constantly remake our identity. And if there’s anything the women around me are good at it’s rebuilding themselves, and I cannot see that as anything but a gift. I’m rebuilding myself from the inside right now. But how do we stop reducing ourselves – carving our bodies away until we’re bone? How do we value the messy, hidden woman inside? I can only think it’s from a place where gender does not tell our complete story.