Portrait of Te Waipounamu: A Review of Hidden Light

Simon Palenski considers Christchurch Art Gallery's latest photography exhibition, Nathan Pohio, and the story of Aotearoa.

Simon Palenski considers Christchurch Art Gallery's latest photography exhibition, Nathan Pohio, and the story of Aotearoa.

A few months ago the exhibition Hidden Light: Early Canterbury and West Coast Photography, curated by Ken Hall, opened at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Hidden Light places the viewer in Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha in the midst of British colonisation in the 1840s. This is the time of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Canterbury Purchase (better known as Kemp’s Deed), and the formation in England of the Canterbury Association. It is also the time when photography – an emerging, ground-breaking technology – arrived in the region and possibly, as the exhibition posits, the first time it was seen in Aotearoa altogether. The photographs in Hidden Light are arranged chronologically, from the 1840s to about 1900. Many of these images have never before been seen by the wider public.

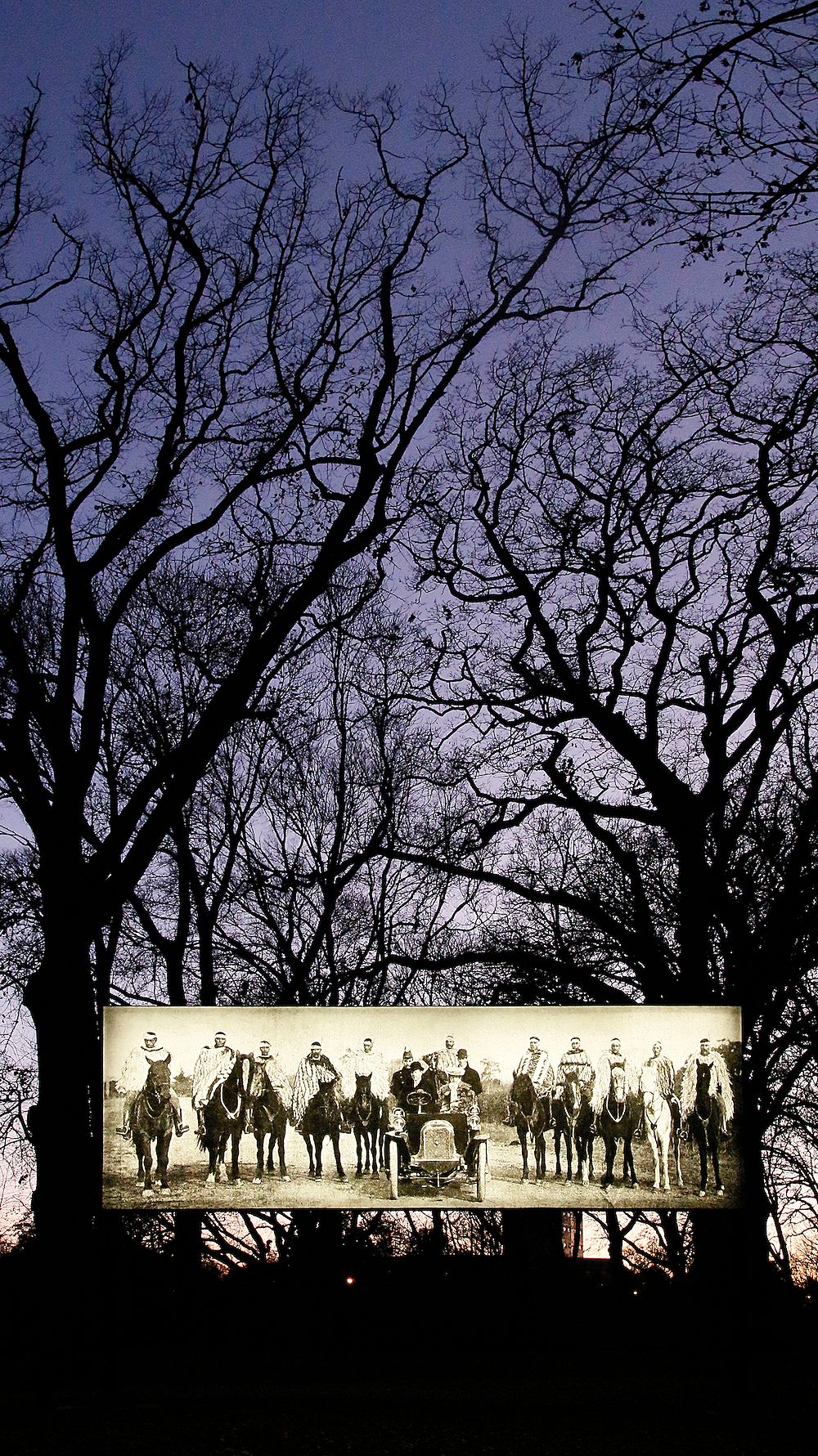

Around four months before the exhibition opened, Raise the anchor, unfurl the sails, set course for the centre of an ever setting sun! (2015) – a nearly two-and-a-half-metre-high, eight-metre-long photographic installation by Ōtautahi-based artist Nathan Pohio (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu) – was given a permanent place in Little Hagley Park near Harper Avenue in Ōtautahi. Raise the anchor has travelled long to get to here, from Memorial Park in Ōtautahi in 2015, where it was first shown as part of SCAPE 8; to the forecourt of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki for the 2016 Walters Prize; then to the EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, Greece, where a new version featured a second archival photograph taken at the same time but previously unused by the artist; and to Weinberg-Terrassen in Kassel, Germany, for documenta 14. The original photograph Pohio sampled for Raise the anchor dates from a 1905 issue of the Canterbury Times, just after the time period that unfolds in Hidden Light. In it, horse-mounted Ngāi Tahu rangatira in ceremonial korowai and kākahu stand in a row directly facing the camera, flanking Lord and Lady Plunket – the then-Governor-General and his wife – who sit in a small motorcar. Both Hidden Light and Raise the anchor have a quiet, yet insistent, historical resonance that emanates from the photographs that Hall has brought out, and that Pohio has reconfigured on a monumental scale as a public artwork. This resonance, although subtle, can hold our attention when we look, as the subjects depicted are suddenly immediate. They show us a past that is present, but is typically invisible to the naked eye.

...the questions of whether photography at this time operated as an arm of this colonisation, and whether photography can ever be separated from this process, are also unanswered

There are around 100 photographs in Hidden Light, from daguerreotypes to ambrotypes, from carte-de-visite portraits to a portrait printed on the side of a teacup. All were taken by photographers within the boundaries of what colonists deemed the Canterbury Province, which up until 1867 included Te Tai Poutini. The exhibition title indicates something that has been hitherto obscured. Hall argues that the study of historical photography in Aotearoa has remained focused on Te Ika-a-Māui, while photographs taken in Te Waipounamu have remained ‘hidden’ for the most part in archival collections, also in Te Ika-a-Māui. But the question of how tightly the history of Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha and Te Tai Poutini during this period continues to focus on settler narratives remains unanswered: how these narratives are remembered at the expense of histories that instead outline the colonial and commercial exploitation that enabled this settlement (such as the history of Te Kerēme, the Ngāi Tahu Claim against breaches of land-sale contracts and Te Tiriti, which began in 1849). Furthermore, the questions of whether photography at this time operated as an arm of this colonisation, and whether photography can ever be separated from this process, are also unanswered.

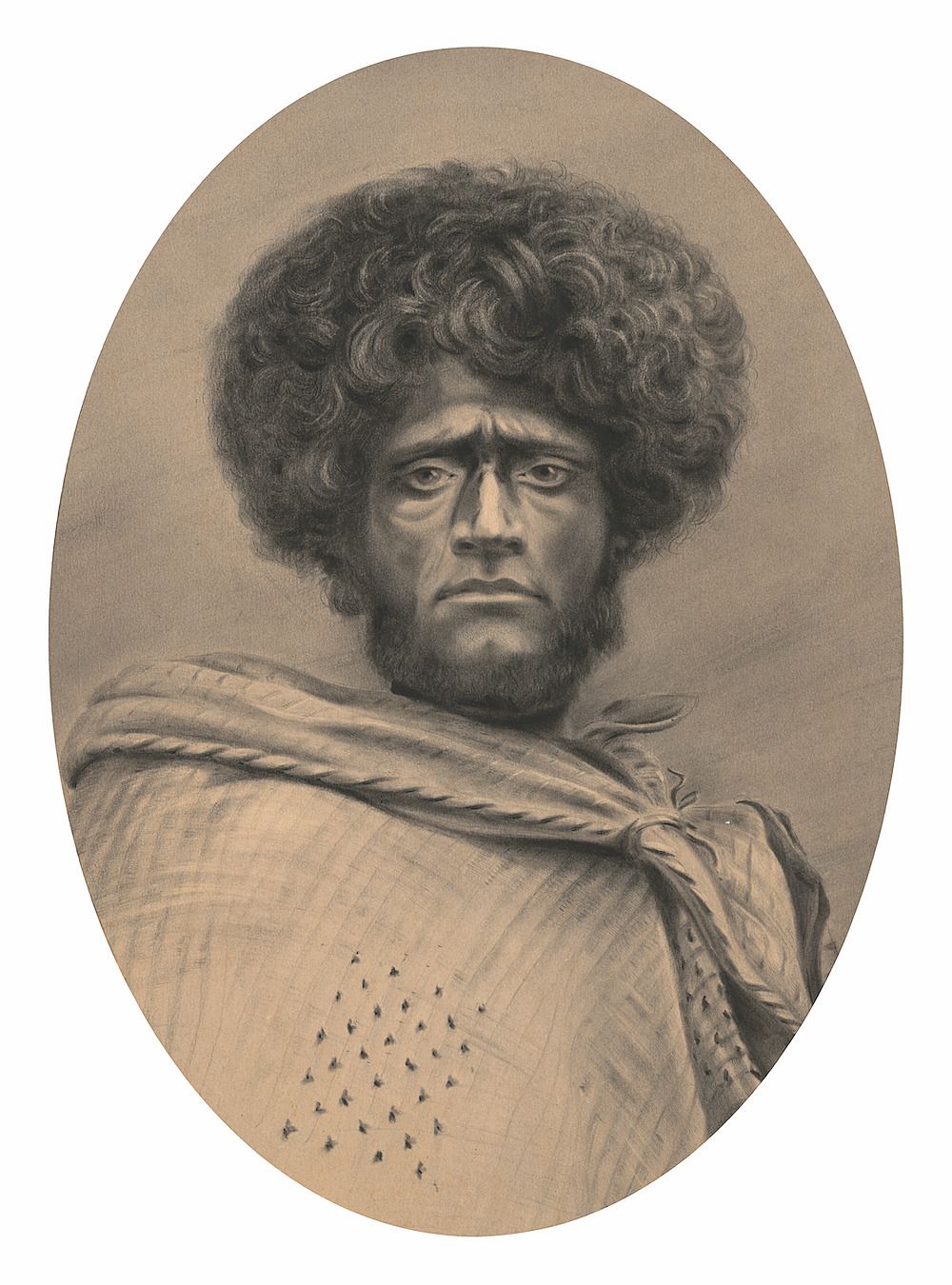

In Hidden Light, photographs are framed and hung across the charcoal grey and white walls of a dimly lit gallery. They also lie within Victorian frames, carte-de-visite holders or viewers, and in albums inside perspex display cases, or are cast onto a blank wall by a digital projector that silently clips through each image. During its run, the exhibition will see changes; some photographs will be swapped out, and the pages of some albums will be turned to reveal new images. The first ‘photograph’ the visitor likely encounters is actually a digital print of a charcoal drawing by Charles Méryon – a copy of a daguerreotype portrait taken by an unknown photographer of, it is believed, Piuraki, also known as John Love (Hone) Tikao, a Ngāi Tahu rangatira. The true daguerreotype’s whereabouts is unknown. Méryon’s copy of it, dated 1846, which has been printed onto the wall next to the introductory wall label, is in the collection of the National Library of Australia. In this portrait, a kind of afterimage, Tikao faces the camera’s lens, but his gaze seems to be fixed over the viewer’s left shoulder. He wears a large cloak, maybe a kaitaka, wrapped and tied across his left shoulder. Hall makes a case that Méryon’s portrait of Tikao is the first evidence of photography in Aotearoa, but more interesting is how this image, at the beginning of an exhibition of early Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha and Te Tai Poutini photography, goes beyond this quite narrow, geographical category and outlines how this story or history is far more global. Tikao himself was a sailor on a French whaling vessel for a number of years during the 1830s, lived in France and England, and learned to speak French, German and English before returning to Akaroa near the end of 1839 (Tikao’s nephew Hone Taare Tikao retold Tikao’s story to James Cowan, who wrote an article based on it for The Akaroa Mail in 1918). The unknown maker of the original daguerreotype was perhaps a naval officer on board Le Rhin– a French warship sent to Akaroa in 1842, on which Méryon was a cadet –or another visiting French warship. Or perhaps the maker was Didier Joubert, the French businessman who was associated with the first daguerreotypes taken in Sydney in 1841, who is known to have spent a week in Akaroa in 1842. There is also a link between this daguerreotype and Pierre-Marie Alexandre Dumoutier’s plaster life-casts: when sailing around Aotearoa on Jules Dumont d’Urville’s Astrolabe voyage in 1840, Dumoutier made a cast (one of many) of a Ngāi Tahu man at Ōtākou, who could also be Tikao. Dumoutier’s casts were soon documented in daguerrotypes, and copied and published as lithographs once the Astrolabe returned to France. Many years later, these casts would be rephotographed by artist Fiona Pardington (Ngāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāti Kahungunu, Scotland) in her series The Pressure of Sunlight Falling. Despite the questions around the provenance of this opening image, the lost daguerreotype portrait of Tikao provides an example of how photographs and images of photographs – even at this time – transmuted form and were rapidly disseminated, and were tied to the movements of peoples and the processes of colonisation, rather than region.

Hall tells me that he believes there would have been hundreds of daguerreotypes and thousands of ambrotypes taken in Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha at this time, of which only a handful have ever been found. Among those, a few have made it into Hidden Light. These early, usually half-plate, ambrotypes are extraordinary objects. Often housed in a small, ornate frame or velvet case, the emulsified images in each are captured in glassy grey tones, and their surfaces are run across with cracks and stains. Most locally well known from this period are the photographs of Alfred Charles Barker, taken, at least initially, with a camera he made with a candle box and a telescope. Large reproductions of his glass plate collodion negatives are displayed prominently across one wall. These prints hint at the materiality of the original objects, with the negatives’ cracked edges and murky surfaces being held onto in the ink. This selection of Barker’s photographs focuses on his portraits, mostly of his family, including some of his eight children. But there is also Barker’s well-known shot of the newly constructed Government Buildings in Ōtautahi, another of a group of Ngāi Tūāhuriri men dressed for the welcome of Prince Alfred, and two portraits of farm-hands at Grasmere Station. Having been enlarged, these portraits offer up plenty of detail, particularly of their subjects’ clothes. They feel like biographies rather than portraits, the images curious yet sensitive. The vivid deterioration of the negatives contributes to this, though Barker’s habit of photographing people in his garden, amongst the scraggly branches and foliage, gives them a wild, almost proto-Gothic air compared to the formality of the later carte-de-visite portraits by studio photographers seen across the gallery.

Looking at them, you can’t help but notice how healthy the rivers looked then compared to now, in particular the Waimakariri

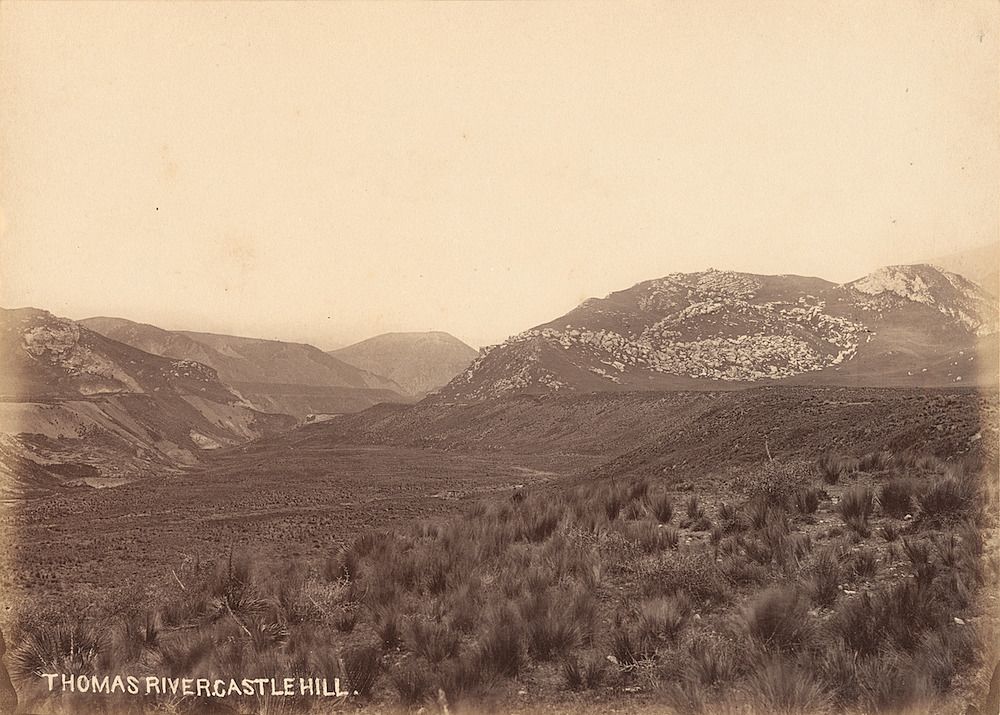

After Barker’s portraits, the exhibition turns towards wider Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha and Kā Tiritiri-o-te-moana. The landscape becomes the focus here, in the photography of Herbert Deveril, Daniel Louis Mundy, Edward Percy Sealy and Hanwell Williams. A solar-enlarged photograph by Mundy of Benmore Station holds a central place on the wall. Many of these photographs are especially beautiful, in particular those of Williams, whose moody landscapes are less pictorial, and instead have a sense of the underlying and raw forms of the land, cast in the tawny and grey tones of the film. At the same time, these landscapes impart the gradual reach of colonial land claiming into Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha’s interior and high country. Sealy’s photograph of the peak of Aoraki is revealingly displayed in an album overleaf from a map study by him of Te Manahuna’s sheep stations and topography: as well as being a photographer, Sealy was a keen mountaineer and the region’s district surveyor, and so involved in the systematic mapping of land that was about to be, or had already been, divvied up between colonists. Deveril’s photographs show this same colonial reach more literally, as he was specifically appointed by the government to photograph its growing infrastructure – in this case, the bridges that had been built to cross the rivers of Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha. There is a starkness in these photographs as the bridges cut each composition across the middle. Looking at them, you can’t help but notice how healthy the rivers looked then compared to now, in particular the Waimakariri. Tussocks, harakeke and other vegetation grow along the banks of each river, and the water is high and blurry as the current whirls by the camera’s long exposure. Similarly, Mundy’s photograph of Benmore offers a glimpse of a more primordial landscape, with harakeke, toi toi and stands of beech forest growing amongst tussocks on the surrounding mountain slopes. Reproduced in the catalogue, but unfortunately not in the exhibition, is a pair of photographs taken in 1871 by Barker of a whēkau (laughing owl) tethered by string to a tree branch, where it turns and fiercely stares down the lens. Within the next half a century, the whēkau would be declared extinct – another victim of the rampant degradation of the natural environment that followed colonisation.

The works that make up the Te Tai Poutini portion of Hidden Light focus on the mining industry, as photographers joined the miners who flooded the region after the beginning of the gold rush in 1864, but there are also a number of portraits and scenic work. Thomas Pringle’s photographs of Kā Roimata-a-Hinehukatere are stunning compositions of dramatic, glacial formations of rock and ice. The glacier was much larger back then – if Pringle were to stand with his camera in the same place today, it would barely appear in the frame. Streetscapes of Hokitika, Māwhera, Kawatiri, Ross and Totara Flat feature rows of weatherboard banks, stores and hotels, and blurry figures caught in motion as they cross the image. James Barrowman and James Ring’s photographs of mining operations, buildings, crushing machines, sluices, and hydraulic pumps settled on blasted and scarred landscapes demystify the pristine grandeur of the landscapes in the rest of Hidden Light. These photographed mining operations are all of coal, the primal, grimy engine of Aotearoa’s growing colonial economy. Hung together, there is an uncomfortable link between the images of coal mining and of the glacier, which has since melted and shrunk.

*

The day I visited Pohio’s Raise the anchor, while researching this essay, was one of the first autumnal days of the year, the cold wind in the surrounding oak trees mingled with the steady rush of cars moving along Harper Avenue behind me. I was on foot, and the installation felt much further from the road than I first thought; when I stood close to the work, the horse-mounted rangatira seemed to eyeball me back. Pohio later told me that he wanted this to happen, for the fourth wall to break down and for the image to grab the viewer by the shoulders, shake them, and tell them you are here. He hopes this action draws attention to the gap around our history in our education and national psyche. It is important for Pohio that Raise the anchor finds something site-specific to draw a connection from in each location that it is installed. When shown at SCAPE, this was the site of a historic Waitaha urupa and the Bridge of Remembrance near Cambridge Terrace; at Toi o Tāmaki, it was Gottfried Lindauer’s portrait of Hakopa Te Ata o Tū which was hung inside the gallery on Pohio’s request,as part of the work. In Athens it was the Phaleron War Cemetery, where several Ngāi Tahu are buried, and in Kassel it was Jacob Grimm’s drawn copy of Sydney Parkinson’s etching The head of a New Zealander which was found by the artist on the Grims Weld Gallery walls, confirming the decision to install upon the Weinberg-Terrassen. In its current place, Raise the anchor draws some of its significance from Little Hagley Park, historically where Māori would camp when visiting the fledgling Ōtautahi, and where a massive Ngāi Tahu delegation camped when they brought their case for a land and reserves claim to the Native Land Court in 1868.

Pohio has said that his practice, Raise the anchor especially, is about excavating information and letting his projects control where and to what they lead him. He was drawn to the original photograph by its astonishing imagery, with the horse-mounted rangatira who appear to be characters from a Western such as John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960). The cinematic impression of the work is sustained by the narrow, but not panoramic, ratio that Pohio has used – a style famously devised by Abel Gance in his silent film Napoléon (1927), and achieved by filming the chaotic battle scenes with three cameras and later joining the footage together into a triptych. Horses themselves are a key motif in Pohio’s work, as in photographic and cinematic history they call to Eadweard Muybridge and his pioneering work in the late 1870s with motion-capture photography of moving subjects, most famously horses, realising the point where photography, painting and cinema merged. Muybridge’s horses have since become a symbol of modernity, and it is significant that horse riding as a practise was quickly picked up by Māori soon after horses were introduced by colonists. Escorting dignitaries by horseback to the gates of the marae, preparing them for the pōwhiri ceremony, sits within this particular notion of modernity.

The idea that historical photographs are colonial encounters and can never be separated from imperialism should cast some doubt on what they can truthfully tell us about the past

Historical photographs, like those included in Hidden Light and repurposed by Pohio for Raise the anchor, can slow us down. We can be jerked out of the vortex of images of all kinds that we see day to day. The idea that historical photographs are colonial encounters and can never be separated from imperialism should cast some doubt on what they can truthfully tell us about the past. However, many of the photographs in Hidden Light do reveal histories that subvert the kinds of settler narratives that are told and retold: Tikao’s engagement with the world on his own terms; the rapid claiming, commodification and despoiling of the land that followed on the heels of land surveyors and spread along the roads and bridges into the open country; the immense coal and wider resource extraction that followed the hallowed gold rush – are all examples of what can be left out in the form of our history that we are typically aware of; one that is simplified and belies complexity.

Pohio’s Raise the anchor disassembles these histories in a different way, although there are similarities beyond the shared historical medium. The stories behind the photographers and photographs of Hidden Light and Raise the anchor outline the itinerant nature of the practice here during the 19th century, despite the shared local significance. The photographers and photographs of Hidden Light travelled widely and were reproduced and exhibited across Aotearoa and the world, mirroring something of how Raise the anchor also travelled and found connections wherever it went, uncovering an arrayed network of our past. Pohio’s Raise the anchor, however, as a billboard-sized installation, is markedly different. The photograph it displays offers an insistent moment in time, snipped out from its immediate before and after. It is a moment – when we catch sight of it – that steps out from historical memory into our path, one we cannot ignore as we go by.

The place names in this essay are from Kā Huru Manu, the Ngāi Tahu Cultural Mapping Project.

I want to acknowledge and thank the people behind the project.