Rapua Te Mea Ngaro, Seeking That Which Was Hidden: A Review of He Taura Here

Ellie Lee-Duncan reflects on hidden identities in He Taura Here at Laree Payne Gallery.

I rest my bedroom door open on a rock, stolen from a gap in the weeds outside the communal dormitory at Hiruhārama, Jerusalem. The dormitory is garishly painted in yellow and lime green, each bed covered with worn and mismatched floral sheets. Thin curtains allowed separation between the beds of strangers, if desired.

I look into this view in Tia Ranginui’s (Ngāti Hine Oneone) photograph Hiruhārama (2016). This site was created by the Catholic Sisters of Compassion, who took in and cared for children in the 19th century, and in the 1970s was where the poet James K Baxter created a community of Māori and Pākehā, focusing on supporting each other. These beds have also been a focus of other Aotearoa photographers such as Anne Noble, Paul Johns, and Elliot Collins.

Baxter wrote of others in the community at Hiruhārama “who waken / early will break the veil of peace / with gunshots” to hunt non-native animals threatening the land.1 Tia herself stayed here as a child during holidays, and remembers being woken in the night by nuns with guns, and told to hold a spotlight while they shot down invasive, introduced possums. This is the bed she slept in. Lurid colours and old flowers seen here in the dusk light create the sensation of a childhood memory, just out of reach.

Hannah Ireland and Heidi Brickell install view.

He Taura Here is an exhibition of eight Māori artists at Laree Payne Gallery in Kirikiriroa Hamilton. The title refers to a cohesive pulling together of bound rope from disparate threads, and people from different iwi. Curated by Laree, these emerging and mid-career artists extend conversations begun in exhibitions such as Toi Tū, Toi Ora at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and the recent Waitohu at the Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato.

Hannah Ireland’s (Ngāpuhi) painted face in Teething (2021) is typical of the artist’s splotchy faces on glass - without an absorbent base of paper to hold the watercolour and house paint, the colours slide freely. The image is distorted, but carries the feelings of the artist who, never knowing her grandmother, was told by a stranger that they could recognise her tupuna in the shape of her nose.

Impossibly fragile, Conor Jeory’s (Ngāti Porou) work Object (2021) is a net with the handle carved from kauri, riddled with the swirls of carved passages. The net is of finely knotted human hair - the artist’s cousin’s, gifted to Conor by his aunt and uncle. Crafted from found materials, the artist’s time-rich process invites intimacy and close examination. Filled with the white stars of artichoke seeds, the net is hung diagonally in mid-air, as if in the action of a catch.

Conor Jeory, Object, 2021

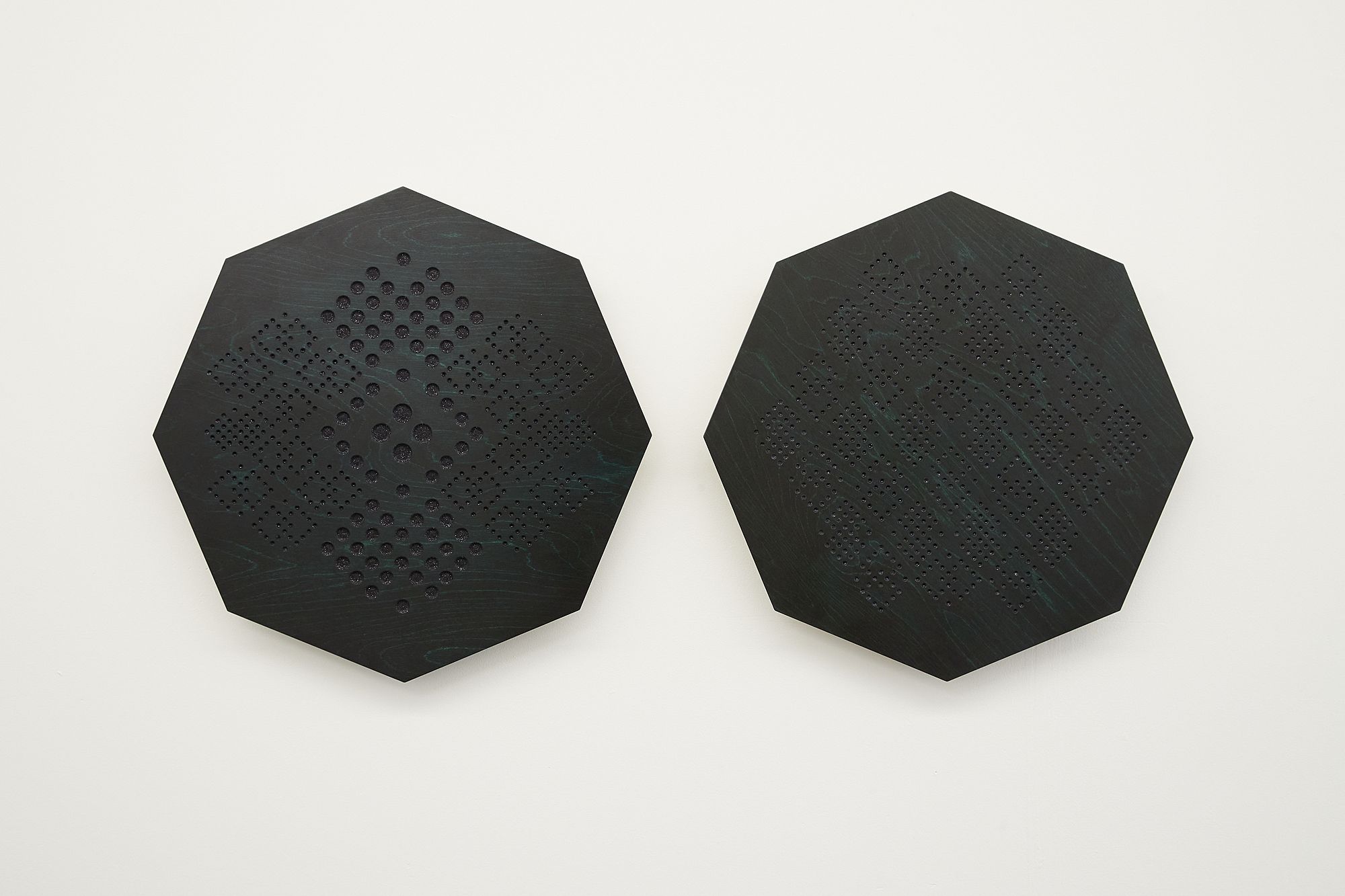

Vanessa Wairata Edwards (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Whakatōhea, Ngāti Kahu) has two works in this exhibition, both hazy wood-cut prints on enamel, and both, unusually, pressed from the reverse side of the wood rather than the carved print itself. The weight on the carved areas pushed through to the other side of the wood, and the printed images only softly emerge. In the front window, Peata Larkin’s (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Tūhourangi) Tongariro I is painted linen, slit patiently into triangle patterns like a tukutuku panel. Maioha Kara’s (Waikato, Ngāti Kahungunu, Te Arawa, Ngāti Porou) two large wooden works are also similar to tukutuku panels or crochet patterns, with their glittered cut insets on dark-stained birch merging her ancestor’s crafts together into geometric patterns.

Kahukura–Maker–Shadows–Whai–Buttons (2018), by Heidi Brickell (Ngāti Apakura, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Rangitāne, Ngāti Rongomaiwahine) is constructed from the offcuts of fibre from stretching her own canvases. Pieces of the fabric are stripped away, pulled together, glued in pieces to construct a new whole. The novelty of this process facilitates a highly personal wānanga for Heidi, who is interested in the fluidity of mātauranga Māori, "a continuum of knowledge with Polynesian origins, which survives to the present day, albeit in fragmentary form"2, and discovering what it means to see it embedded in her own psyche as a living, articulate force.

Jade Townsend’s (Ngāti Kahungunu) Soft cultural celebration (2017) has delicate threads of turquoise and rust-coloured fishing line, fringed with stamens, and dripping into the hanging heavy buds of pearls. Homesick for Aotearoa, while Jade was living in Thailand (pre-Covid) she would walk along the beach daily and gather the debris of discarded fishing nylon washed ashore.

Jade Townsend, Soft Cultural Celebration, 2017

Adding the stamens from Indonesian paper flowers to the sculptural quality of the unravelled fishing line, Jade stitched these, together with Chinese cultivated pearls, onto a postcard of a korowai from Te Papa - the artificial cultural debris entirely effacing the image from home. These express Jade’s experience of the “constructed idea of paradise”, inorganic, overwhelmingly polluted, and her attempts to retrieve elements from this “cultural debris”.3

Each of these artists is weaving together and reclaiming parts of themselves from cultural resources - precious, sometimes fragmentary, sometimes rediscovered, sometimes passed down. I was thinking of this in relation to the whakataukī “rapua te mea ngaro”, actively seeking out their hidden aspects of identity. While considering this, I looked up the word “ngaro” for all the other meanings and connotations. I found this treasure:

“Ko te wāhi e tārewa ana ko ngā roto kei waenganui i ngā whenua, ko ngā parumoana, arā ko ngā whenua e pā ana ki ngā moana, e ngaromia ana e te tai pari. Ki te Māori he whenua ēnei nōna: The part still unresolved relates to lakes within the land and the seabed, that is the land associated with the sea which is covered by the high tide. To the Māori this land belongs to them.”

Maioha Kara, Kānapanapa II and Kānapanapa III, 2020

As someone who calls Aotearoa home, and is trying to uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi, I often try to prioritise writing on tangata whenua artists. Of course, I will never wholly understand the specific negotiations these artists make with their identity. Even when I get things wrong, I feel this is my responsibility as an ally, and part of my passion to tautoko/support those whose whakapapa or identity has historically been marginalised.

I’m also on my own adventure of rapua te mea ngaro, meaning to seek that which is hidden; as Queer and non-binary, as highly disconnected from my European tūpuna, and as someone whose Chinese ancestry has been intentionally hidden out of historical cultural shame for generations. I think I’m the only living member of my family who passionately celebrates Chinese New Year, following traditions not handed down, but researched on Ecosia. I’m on my own journey, patiently lifting heavy rocks to look beneath them for hidden treasure.

Claiming identity is not discovering anew, but is an uncovering of self already there, like the latent land under sea. The artists in He Taura Here have been generous in sharing a small part of their own journeys here, communicating it in a way that transcends the limitations of written language. As the quote from Te Toa Takitini says, “this land belongs to them” even though briefly concealed by the flow of the tide.

He Taura Here

Laree Payne Gallery, Hamilton

27 January – 20 February 2021

Feature image: Tia Ranginui, Hiruhārama, 2016. All images courtesy of Laree Payne Gallery.

1 James K. Baxter, “Winter in Jerusalem,” in An Anthology of Twentieth Century New Zealand Poetry (second edition), selected by Vincent O’Sullivan (Wellington: Oxford University Press, 1976), 298.

2 Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, "Politics and Knowledge: Kaupapa Māori and Mātauranga Māori" in He Hautaki Mātai | New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 47, No.2, 2012, p. 33.

3 Jade Townsend, in conversation with the writer, Kirikiriroa Hamilton, 29th January 2021.

Editorial note: The previous version of this article incorrectly quoted one of the artists mentioned. We have removed this quote at the artist's request, and have replaced it with an accurate quotation.