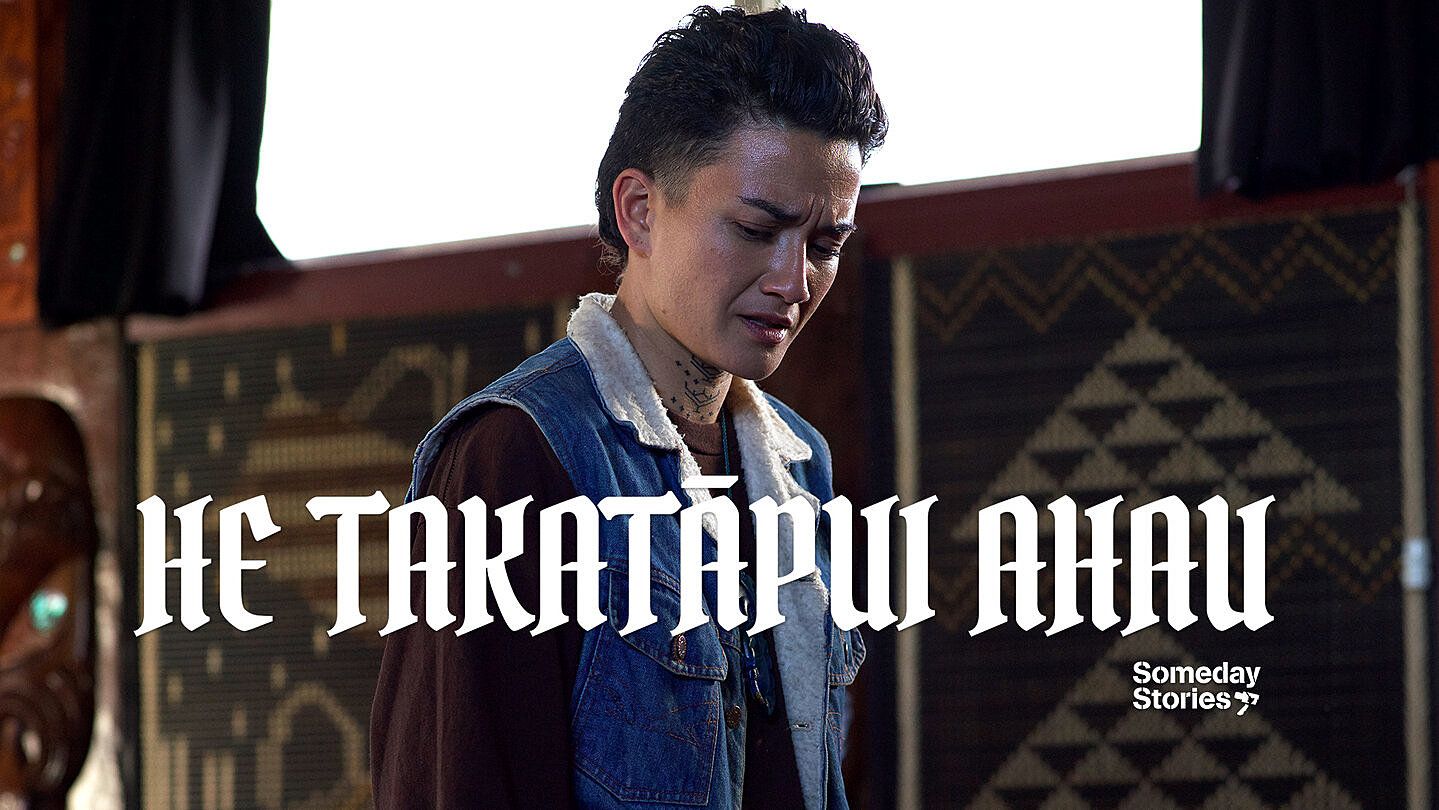

He Takatāpui Ahau

Sinead Overbye with her gorgeous boo, filmmaker Alesha Ahdar, on making a film that the takatāpui community is proud of.

As a part of the Someday Stories short film series, this month a film about a takatāpui non-binary person’s experience of returning home to their marae was released online. He Takatāpui Ahau was written and directed by filmmaker and multi-disciplinary storyteller Alesha Ahdar. As well as being an amazing filmmaker, they are also my gorgeous boo! Because of this, I was lucky enough to be witness to the creation of He Takatāpui Ahau.

In May, we travelled to Auckland to film over two days. The filming experience was new and intense, but Alesha brought a sense of calm and peacefulness to the set, making the experience memorable and lovely for all involved. We sat down to talk about their filming experience, and what He Takatāpui Ahau means for the takatāpui community.

*

Sinead Overbye: We’re here to talk about your film He Takatāpui Ahau. Tell us what the film is about.

Alesha Ahdar: The film is about a takatāpui non-binary person who has decided to go home to their marae for the first time since coming out to their everyday community. They have borne witness to homophobia and transphobia in the past from their family, and they’ve seen it on the whānau Facebook pages, so they don’t know how it’s gonna go.I think that the main character was right in being nervous to go home, because it was what they thought it was going to be. But then they find acceptance in an unexpected place.

I think the film is like a manifestation of my own personal fears. But it’s also my own hopes for myself and everyone like me. I want them to feel comfortable to go home to their marae and find acceptance. But it’s not just on us takatāpui to create that comfort at home; we need to be met halfway.

SO: What does ‘takatāpui’ mean to you?

AA: Well, regarding my own identity, ‘takatāpui’ for me means that I am queer and non-binary. I use all pronouns – she/her, he/him, they/them, daddy (laughs). But also, ‘takatāpui’ is a form of resistance. It’s resistance against what the coloniser did to Māori in bringing homophobia and transphobia to our lands. And it’s also like, resistance to the Western idea of the LGBTQIA+ community, because it’s different when you’re Indigenous and your queerness or gender identity is directly linked to your whakapapa. It’s directly linked to you being Māori. We all know, so many rainbow spaces are racist. And I wrote a poem about it! Or, I wrote a rant about it. That’s takatāpuitanga to me, it’s resistance and it’s a direct link to your whakapapa Māori and pre-colonial Māoridom.

That’s takatāpuitanga to me, it’s resistance and a direct link to your whakapapa Māori

SO: I guess that’s why I really like ‘takatāpui’, because, from what I understand, it’s like your Māoritanga comes first and then your gender identity and sexuality. But I feel like some other people are defined by their sexuality and gender as if they don’t have culture. But I feel like with ‘Takatāpui’, culture comes first. I’m Māori, and everything else is just linked with being Māori.

AA: I agree with that, but then I might say that whakapapa comes first. I also like using the word ‘Takatāpui’ because the word itself has gone on its own haerenga and has been evolving since the 1980s. It no longer means ‘same-sex partner’. It does, but now it means so much more.

SO: It doesn’t just mean ‘close friend’ anymore.

AA: Yeah! It means so much more. And because everyone I know who uses that word, we’re all so different, but we’re all also together. There’s a togetherness. It’s like a cool club!

*

SO: What do you think people would see, or what do you want people to see, in the main character, Blayke?

AA: I hope that, for one, the takatāpui community might see someone who’s like them. I hope that when people see Blayke, they see themselves represented or their community represented. Because the person who performs as Blayke is a part of the community, is non-binary. And so I hope that when the community sees Blayke, they see themselves. Almost 80 percent of our cast and crew was either takatāpui or a part of the LGBTIA+ community. Which is very cool and done on purpose.

SO: Why was that important to the film?

AA: I guess there are a few reasons. Many of our cast and crew were people that we already knew, who we already loved. People we know in real life. Another was for the Fourth Cinema methodology, which we tried to put into practice, which is basically: whoever you’re representing is represented in all other aspects of the film, not just on the screen. (Shout out to Barry Barclay and Merata Mita – if someone could send me Barry Barclay's book Our Own Image, that’d be great!)

And also, just for safety. It’s nice to be on a set where there’s not much explaining to do and everyone kind of just gets it. Even though on set people were still learning about takatāpuitanga. It felt like a good space for people to learn about this part of takatāpuitanga.

They’re [Blayke] just going home to their marae as their full self; that’s the journey that they’re on

SO: I really like how we get to see Blayke with all of their friends at the start of the film. I feel like a lot of Māori and queer content can be kind of bleak and depressing, but in He Takatāpui Ahau we get to see Blayke being peaceful and joyful and with their friends.

AA: It was important for me to make it very clear that Blayke is already out. Blayke knows exactly who they are. They’re just going home to their marae as their full self; that’s the journey that they’re on. That’s why I loved having their ‘chosen family’ there. I loved showing Blayke being with their community. And plus, the representation of Blayke’s chosen family is an ode to my chosen family, because I love them so much (hey Lizzie and Levi!!).

We see our community in so many different ways on screen. It’s not often that it’s just straight-up wholesome vibes. And so many members of the community that I know are so wholesome with each other. Super cottagecore! But you know, as an example, there’s no drugs or alcohol involved in this film. And drugs and alcohol tend to be a huge part of the representation of our community on screens. It is a part of our community, but it’s not the only part.

*

SO: How did that feel, directing a film for the first time?

AA: Filming was such an intense experience. I’m not going to glamourise it, because it was really hard. Especially when you’re making a film for your community, who are underrepresented in the media and in film crews. The pressure is huge. And even though it was a beautiful weekend, and it was nice and calm – you know, I wasn’t like those directors you see in Hollywood movies who are just yelling at everyone. I was the opposite. What I was putting out there was very calm, but I felt a lot of responsibility. It was a very serious weekend for me.

It was really lovely to have so many people on set who were close to us. We basically had a noho weekend, where we stayed on the marae. It was really nice to have a marae being fully run by takatāpui people. But, yeah. It was great to have such gorgeous support!

It was such a huge undertaking. But that was why it was so nice having people like cinematographer Fred Renata, actress whaea Tanea Heke and other elders like whaea Ngaronoa Renata there. It felt like it’d be okay.

It was a rollercoaster. Balancing being super grateful, pumped and motivated for my community, but also feeling the intense pressure of doing this. Doing it for the first time and for your first time, having it available online for free when released. It’s such a public debut; it’s not like it’s going into cinemas. Anyone in the world can watch it.

It’s daunting, but I’m ready and I was always ready, so that maybe some takatāpui people’s lives could be better for it, and maybe some whānau members might be motivated to become more accepting and loving towards their takatāpui whanaunga. At the end of the day, it’s pretty scary but it might help the world become a better place. So it’s worth it.

I hope our wider Māori community will consider helping their takatāpui whānau come home

SO: How was it working with your cast and crew? You had some big names there. And before you shot, you had already had time via Zoom and on the marae for whakawhanaungatanga. What do you think it meant to them to be involved in the film?

AA: I know that filming meant a lot to everyone who was on set. I feel like there was an acknowledgement that this is a pioneer film. Tanea was really excited to be a part of it because she wants to make the world a better place for her moko. So anything she works on, she wants it to positively impact their lives. This meant so much to me, that she was so on the kaupapa. And also, having Fred there, he’s a well-known cinematographer who worked on films such as Merata Mita’s Mauri, it felt like they were really tautoko-ing us as young people. Like, they are our tuākana, but also in some ways we are tuākana to them.

SO: What do you think that you were giving to them, knowledge-wise? What did they take away from it?

AA: Definitely the overall kaupapa and message, and having the opportunity to reflect, in case someone they know is transgender or non-binary. For them to know that… well basically, that in te ao Māori, we all belong on our marae. I think that would’ve been cool for them. I hope so.

SO: I want to pick up on that, the idea that in te ao Māori we all belong. That seems to be a big purpose of this film, to be a conversation starter.

AA: First and foremost, I hope that the takatāpui community feels hopeful and heart-warmed. But also that our wider Māori community will consider that maybe they might want to help their takatāpui whānau members come home. Or perhaps they might reach out… and that’s not for me to say how any marae should run, it’s just an example of a best-case scenario situation for a takatāpui person. For them to find that acceptance and know that they belong there.I also just ultimately hope that our Māori communities will self-reflect. I hope that other people will find it a very self-reflective film, too.

That is just straight-up logic, for me. No one can tell me that we’ve never had any tūpuna takatāpui

SO: What do you think people need to reflect on?

AA: I think the beautiful thing about film, and this film, is that people are privy to the experiences of someone that they otherwise would never know about. And so maybe people could consider that what they think is funny, for example transphobic or homophobic jokes, might not be that funny. And, you know, what people talk about in their kitchens and on their whānau Facebook pages might be stopping people from going home to their marae, and that maybe we should think about that.

SO: I totally agree. And I think this film really will prompt those kinds of reflections. I like the idea of He Takatāpui Ahau being a hopeful story, a positive story, a best-case scenario, as you put it.

AA: Yeah, I just think marginalised communities need to see hope on their screens, and I think takatāpui need to see themselves on screens. Like, we see the Gay male best friend all the time on screens, but we don’t see, like … takatāpui means so many things to so many different people, so here’s another point of view that we’ve never seen before. So, yeah, a bit of hope.

SO: Did you want to say anything about the experience of learning about tūpuna takatāpui that we don’t know about?

AA: I don’t know how much to tell you. Basically, Blayke goes home to their marae, and they discover tūpuna that were just like them. I think that that is just straight-up logic, for me. No one can tell me that we’ve never had any tūpuna takatāpui. The kupu that we use, for example, the word ‘non-binary’, that’s new. But the āhua and the way of being, that’s not new, and I just won’t accept anyone telling me otherwise. No fucking way!

*

SO: It’s so interesting having oral histories and thinking that many of those tūpuna may have just fallen off the radar, or away from what we know about. But they definitely existed. I think you’ve written a fantastic script.

AA: It was hard to write that script. I got really protective over Blayke, the main character, I didn’t want anything bad to happen to them. Even though I know that something has to happen in a film – there have to be challenges and obstacles and character development – it took me ages to find peace with it.

SO: Anything else you want to say about the filming experience?

AA: It was really nice having my boo on set. It was nice having takatāpui on set being takatāpui on a marae. It was really powerful to be able to put into practice what this film is about.

SO: I was very grateful to be there, supporting you. Can you tell us what’s next for you?

AA: Nothing. I’m giving up; I didn’t like it! [Laughs.] What’s next? I dunno, I would like to see more takatāpui people go into the writing and directing space.

I also have to point out that this is a ground-breaking film, right?

SO: I also have to point out that this is a ground-breaking film, right?

AA: It is. This film is world history, not only for its content, but it’s the first film about a takatāpui non-binary person, which is also written, directed, produced and edited by takatāpui non-binary people. And that’s how it should be.

I’ve actually got a bone to pick. Like, you know, some funding agencies, for example, they’re like, “Oh, we want diverse stories and diverse voices”, but they’re not actually willing to put in the groundwork to get those voices to where they expect them to be. I never knew how to write a script before this. My friend Ashley Williams taught me how to write a script by putting Post-it notes on a mirror.

I’m really lucky that several people supported this idea so much that they helped me learn how to present it the way the industry wants you to. People want these diverse voices but aren’t willing to help them learn.

If anyone out there has a spare $120,000 to make six new films by takatāpui for takatāpui, hit me up!

SO: What would helping them look like?

AA: I just think the problem is that writers are not the only storytellers. But for something like a film to be commissioned, it must be written, and it must be written in a complicated, specific way, right down to what font it is, what size it is. It’s so specific, how that story has to be presented to funders. And I think that that is a huge problem. Because everyone says, “Māori history and oral storytellers”, but if you want diverse voices, why aren’t you willing to hear those stories in diverse ways?

SO: So that is a huge barrier, then.

AA: Yeah, I think that it’s a huge barrier because not everyone’s a writer, but so many people are storytellers. And also, in this industry, you do months, years of work for no money to maybe have your film commissioned. So you have to be privileged to afford the time and resources that will get you to that stage.

I’d actually love to see more opportunities for new and emerging filmmakers. So if anyone out there has a spare $120,000 to make six new films by takatāpui for takatāpui, hit me up! [Laughs.] It’s really shit, though, so many people have stories to tell, but the process of getting your story into a script is really complicated. I’m not really a writer like that, which is why I’m thankful for the support I had to get it there.

SO: Do you wanna say anything else?

AA: Sinead’s cute! [Laughs.] And thanks, Someday Stories!