Growing Up Queer

It wasn't easy growing up queer in 1970s rural Otago. Emer Lyons pays tribute to The Changing Shed by Michael Metzger.

A few months ago, I read Maggie Nelson’s tribute essay to Eileen Myles, in which Nelson writes:

Eileen's particular manner of wielding the personal in public provided me a way to think about the personal in public – how to continue violating my own privacy in my work, an art which has always come naturally to me, for better or for worse – without the antiquated baggage of the ‘confessional.’ That doesn't mean there's no shame in the project. It means there's a productive dialectic between one's bravado and audacity, on the one hand, and a startling – indeed shameless – exploration of powerlessness and shame, on the other.

Leaning into shame through autobiographical performance can instil power in the performer and the audience, through both the shared and startling elements of the narrative. Michael Metzger threads the track of queer bildungsroman, familiar to small town quares from rural Otago to rural West Cork, and startling those who find this story unfamiliar. This unsettling power play opens a dialogue between the performer and the audience, a dialogue that moves beyond the play into minds. The personal is political. The personal is worth repeating.

The (un)embodied reality of growing up queer in rural Otago

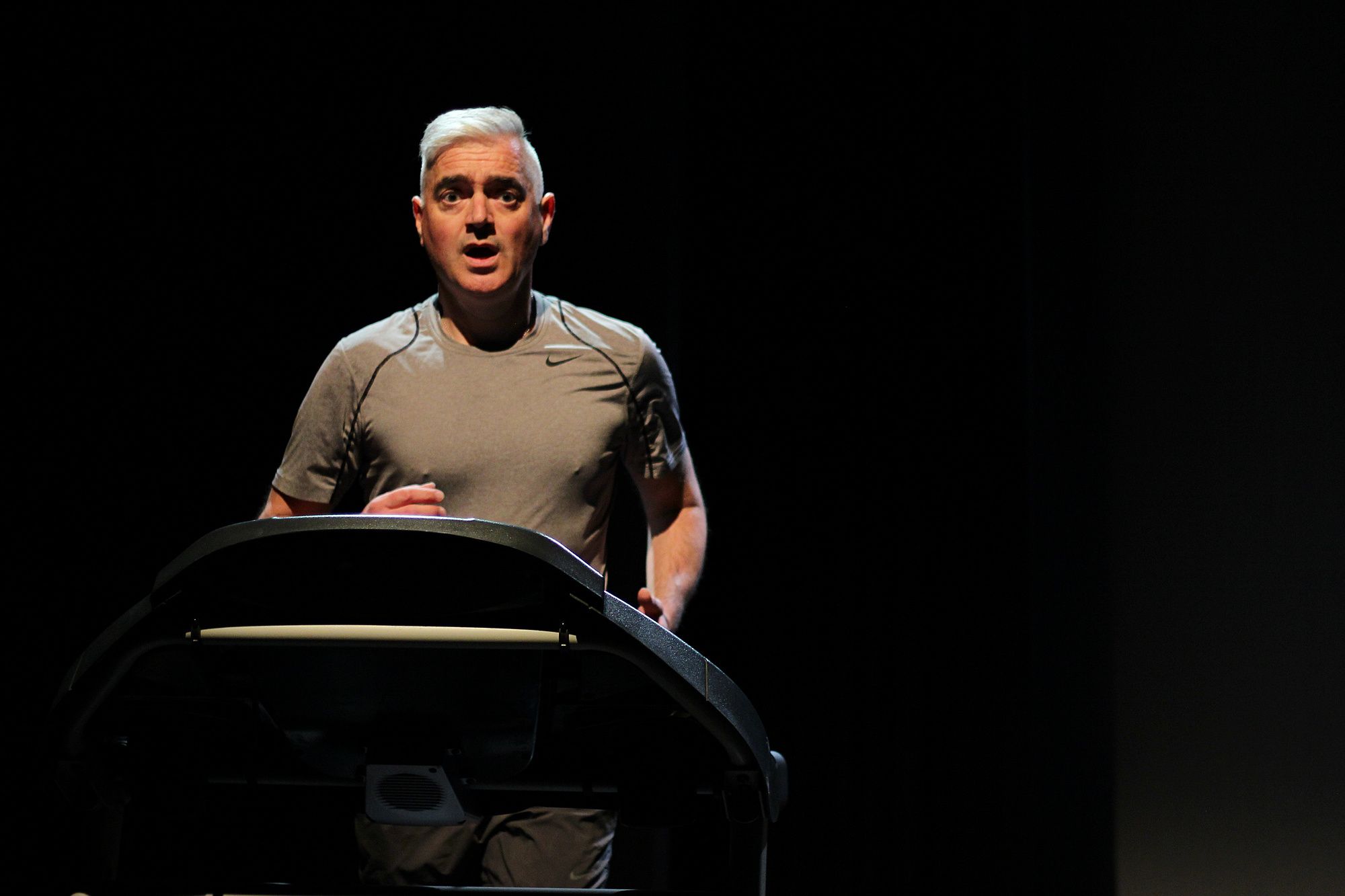

The Changing Shed is an active remembering by Metzger of the (un)embodied reality of growing up queer in rural Otago. Watching Metzger’s one-man show dredged up memories of fearing my body and its physicality as a teenager and into my twenties. He never stops moving during the play. He runs on a treadmill, he shapes the exterior of the changing shed on the floor in white tape, he punches a punching bag (not metaphorical, a real punching bag) after knotting and heaving it upright on a rig, he makes a flower arrangement. The play is a result of years of stillness, of being unable to move in the world at his full physical potential.

Michael Metzger in The Changing Shed. Photo credit: Jordan Wichman.

Metzger addresses the silence of the bullying he experienced in the changing shed by moving around it. Vignettes of memories inhabit the space, with Metzger’s athletic ability at the core. He is now physically fit. And angry. Rage is different from anger. Rage protects the self against further exposure and further experiences of shame by both insulating the self and actively keeping others away. Anger directly invites contact in order to get one's needs met.1

Metzger feels compelled to suppress his anger. People tell him he is nice. As he punches and sweats and punches and sweats, we see anger leak from him. He says he is not nice, but timid. I know this differentiation well. Physical education in secondary school haunted me each week. I would ‘forget’ my gear or engage with minimal enthusiasm once forced by the teacher. I didn’t care to win. I somehow found myself on the hockey team, once. That once, I played for five minutes. I kept to the wing and prayed the ball would come nowhere near me.

I was a queer kid who didn’t know I was a queer kid

I was a queer kid who didn’t know I was a queer kid, at an all-girls Catholic school in West Cork, Ireland. I was loud and loved anything to do with performance, not understanding that when I grew out my orange mohawk into long, blonde-highlighted, straightened locks and tried to find a boyfriend, that I was engaging in performance. At the same time, I wasn’t a traditional tomboy. Or maybe I was but then I wanted to fit in.

Hanging out with my friends was my primary pastime, usually while we waited outside a liquor store harassing passers-by to buy us booze. Writing this now, I am just back from the gym, where I go a few times a week. I walk everywhere. I don’t drive (an exceptionally queer demarcation). I practice yoga. I am trying more and more as I get older to live in my body, to inhabit it physically in a way that terrified me when I was young.

Queers often feel compelled to be the best in show, the outgoing, extroverted performer. When we are stage performers, the audience confuses the self with the self on stage. The self that runs on treadmills into, away from and towards the past. The anger on stage is performed in The Changing Shed, while being a real emotion. When Metzger steps into the street, people won’t expect anger, even after being told, pointedly, that he is angry.

The dead weight of toxic masculinity permeating like Lynx body spray on a teenage boyfriend’s hairless armpits

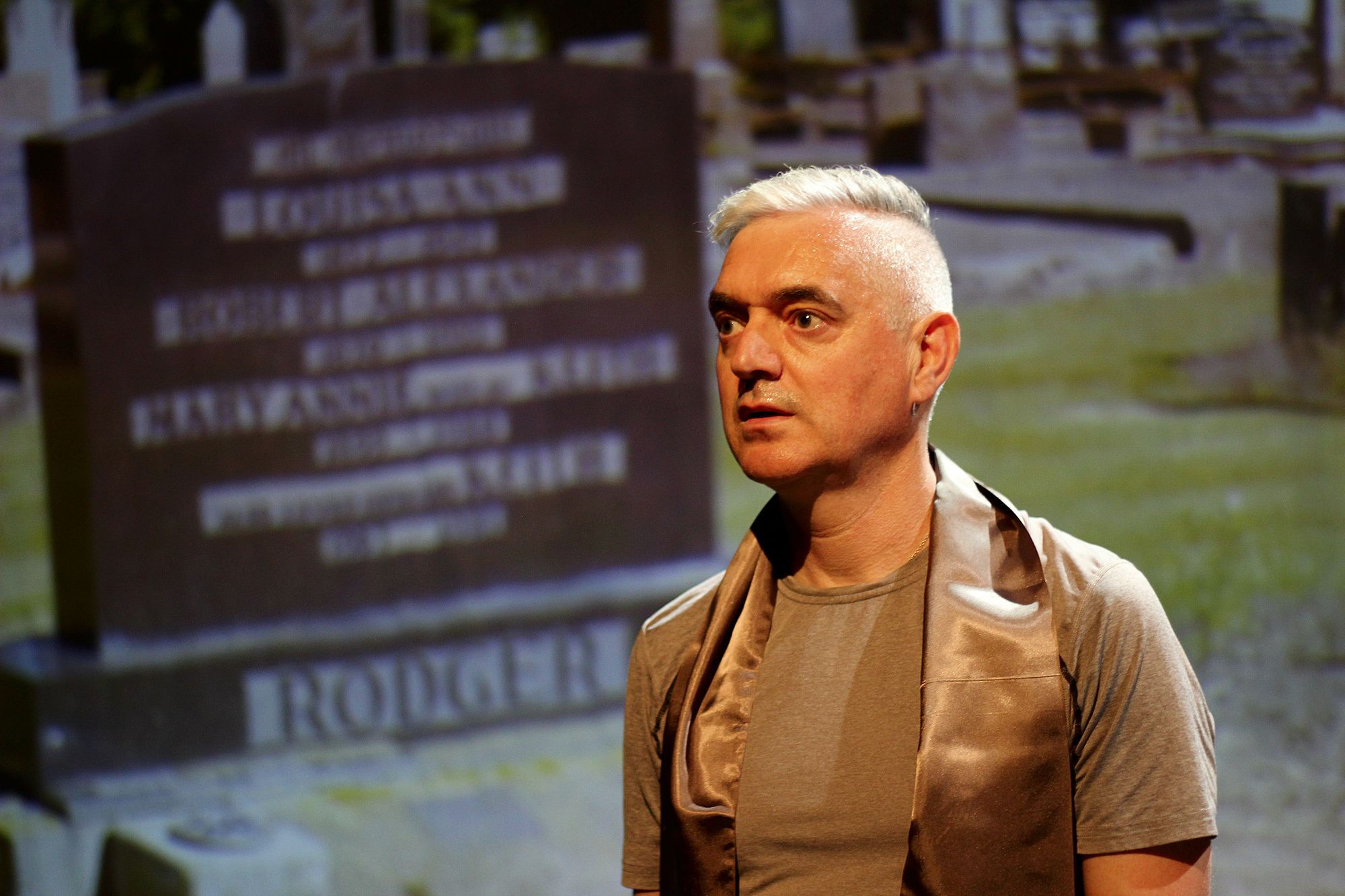

Metzger began work on the play for his PhD through Deakin University, Melbourne. The play was part of the 2019 UNESCO Cities of Literature Short Play Festival, under the title The Killing Shed,for which Metzger received a Dunedin Theatre Awards nomination for Outstanding Performance. The iteration I saw at the Dunedin Fringe won the overall prize for Best Theatre 2021. The play, I am sure, will continue apace to rack up accolades because of Metzger’s performance – he blooms like a fresh wound. There is a vulnerability in his body, his anger and timidity scratch each other to intimacy. My mind pauses, circles, replays as he knots and hoists the punching bag. It hangs animal heavy and ready for skinning. It swings and preoccupies. The killing shedbecomes the changing shed becomes all space occupied by the dead weight of toxic masculinity permeating out of bags like Lynx body spray on a teenage boyfriend’s hairless armpits.

Photo credit: Jordan Wichman.

In autobiographical performance, the performer gives pieces of themselves away. Metzger carefully frames the moments he is willing to share. He tapes them off in the space, in his mind. Not every memory is shared, or is a shared memory. The struggle to tell is captured in The Changing Shed through jump-started memories, before the search for words, enough or right, fails to restore the memory whole, and Metzger moves to the next.

There are never enough words or the right words, there is never enough time or the right time, and never enough listening or the right listening to articulate the story that cannot be fully captured in thought, memory, and speech. The pressure thus continues unremittingly, and if words are not trustworthy or adequate, the life that is chosen can become the vehicle by which the struggle to tell continues.2

The Octagon Club was the perfect location for The Changing Shed. The high ceiling reverberated Metzger’s rhythmic trumps on the treadmill. The bare surroundings of the huge space left a clinical silence throughout the performance like the inside of a bell jar.

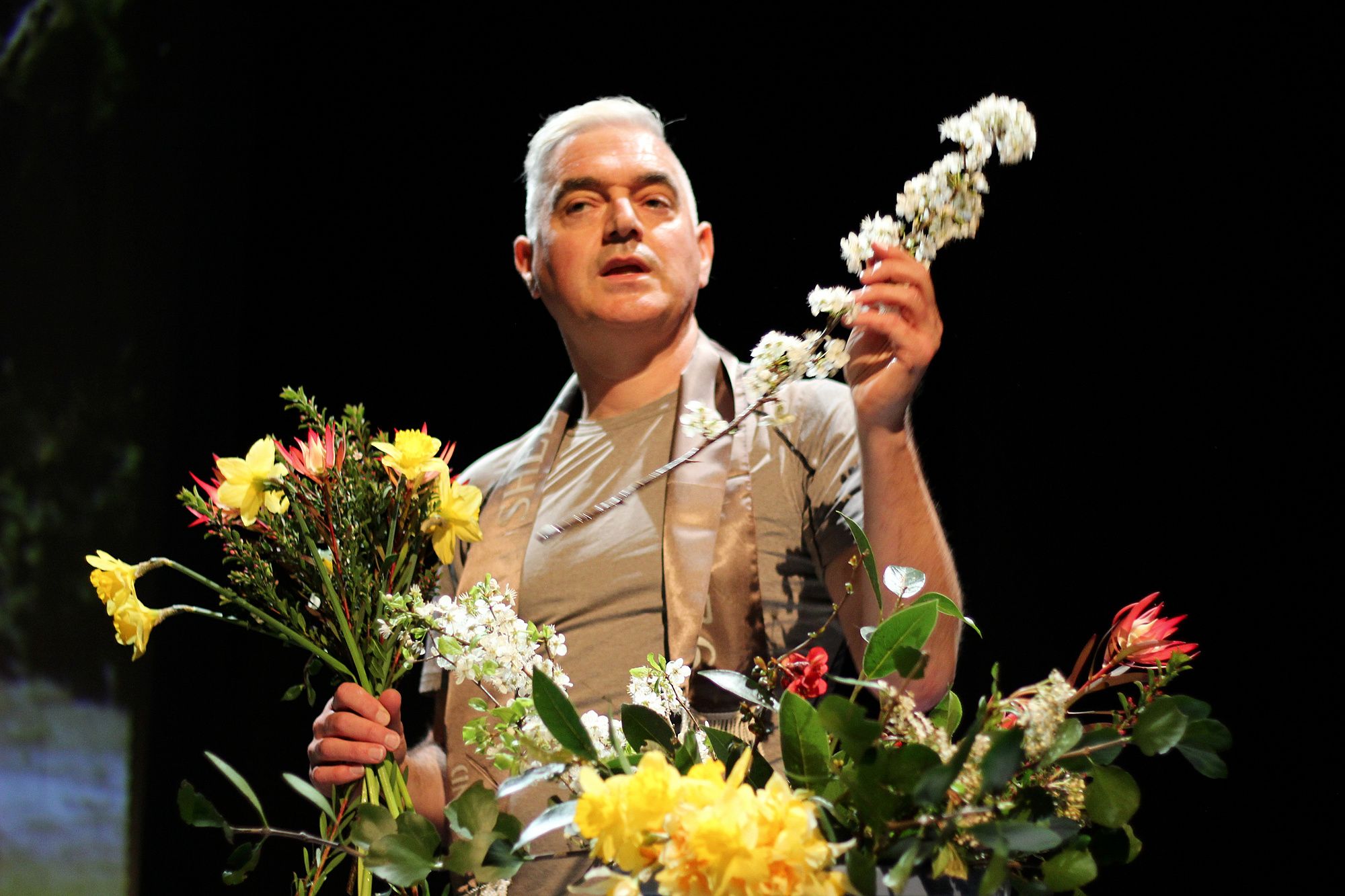

Photo credit: Jordan Wichman.

I am left, predominantly, with the image of Metzger arranging flowers. There is a bucket full of flowers. The props lie around the stage as if by chance, as if without thought. He plucks stem after stem from the bucket as he speaks about his father, displacing/displaying his grief in a bouquet. A bouquet fashioned with precision, spiralling out above and below, seeming to resist containment like a memory. Like the right word.

He bought the flowers himself.

[1] Kaufman, Gershen. 1974. “The Meaning of Shame: Toward a Self-Affirming Identity.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 21(6):571

[2] Caruth, Cathy. 1995. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press. p. 63

Feature image credit: Jordan Wichman