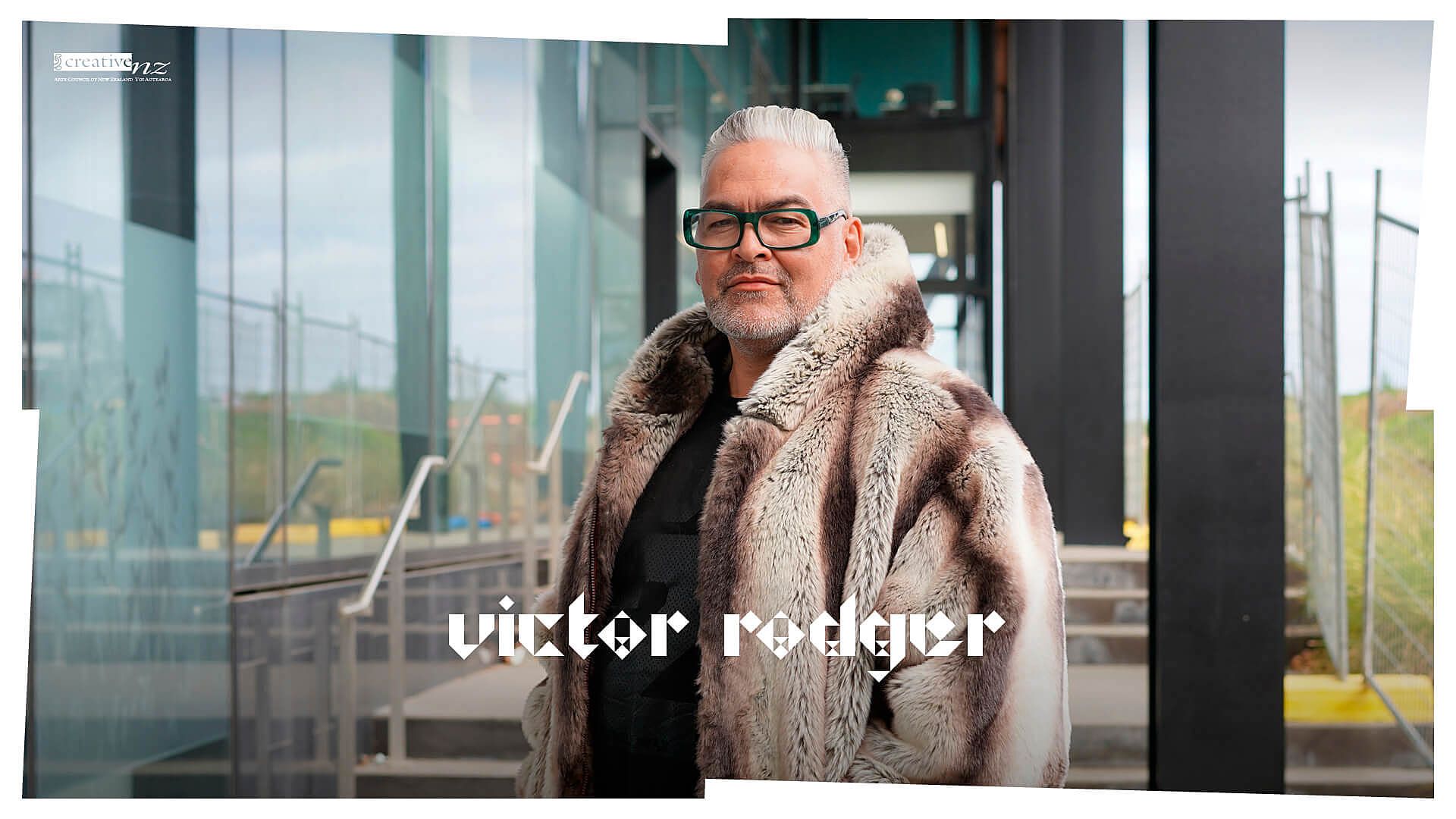

Good little Sāmoan Boy: An Afakasi Story

How did being dressed as a good Sāmoan boy influence critically acclaimed playwright Victor Rodger ONZM to broaden the spectrum of situations and characters presented within the Pasifika canon?

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Christchurch, 1977. I’m seven or so, sitting cross-legged on the front lawn of the house I live in on the east side of town with my mother and my grandparents.

A seven-year-old Victor smiling for a photo to send to his grandmother, Matalena.

Mum is taking a photo of me for my Sāmoan grandmother, Matalena, a woman I meet once in the 70s and once more in the 80s, both times out of sight of my father and most likely without his knowledge.

Mum wants Matalena to know that she is raising a good little Sāmoan boy, even though she herself is pālagi; even though my father – Matalena’s son – is MIA. So Mum has dressed me up as her idea of what a good little Sāmoan boy should look like.

I’m shirtless. Husky, as they used to say back in the day. A junior Poly-Buddha with a fringe. A thick, white shell necklace has been wrapped once around my neck, like a choker, the rest left to dangle in between my nipples. My hands cover my puku – whether by self-conscious design or unconscious coincidence, I’m not sure.

My tongue pokes out of my mouth in an approximation of a smiley pūkana, I am wearing a lavalava for the first time (a gift from Matalena that she made herself, I later learn). It’s watermelon-coloured and features various geometric designs in black and brown. I don’t know how to tie it properly. Neither does Mum. It’s held together with safety pins.

The ensemble is finished off with my mother’s thick, chunky black and silver platform jandals, which already snugly fit my wide seven-year-old feet.

For me, I’m playing dress-ups. No different from putting on a cowboy outfit or a pirate eye-patch. And, like those costumes, the good little Sāmoan boy is something I can put on and then take off, as I like.

The good little Sāmoan boy is something I can put on and then take off, as I like

At the time Mum takes this photo I haven’t given a second thought as to what it means to have Sāmoan heritage, at least not on a conscious level. But whenever I meet the odd Sāmoan relative, with their invariably hard-to-pronounce names and hard-to-decipher accents, I can never get away fast enough. There’s always a level of discomfort. And this is never truer than whenever my father makes one of his rare appearances. The emotions he stirs up are complicated for both my mother and myself. For me, none of these emotions are positive.

Not yet, anyway.

*

I look at this photo of me as my mother’s version of a good little Sāmoan boy over 45 years later, and I’m full of questions.

What did Matalena think when she received the photo? Did she look at it and sigh “kalofae” as she smiled sadly? Did she laugh at the platform jandals? Or was she moved by the effort that my young pālagi mother went to, to try and prove that her fatherless son was somehow still a tama Sāmoa, a son of Sāmoa?

Matalena is long dead. Whatever happened to her copy of that photo? Does it still exist?

Part of me thinks I look ridiculous, especially in those platform jandals. Another part of me recognises that, other than ridiculous, there is something else I look: uncomplicated.

*

It’s decade or so before I wear another lavalava. By then I’m in the first throes of embracing my Sāmoan heritage, but that is precisely when things get complicated.

By the late 80s I’m a young cadet reporter on a newspaper, fresh out of high school. I’m the only brown face in the newsroom. I answer the phone each day with “Talofa, newsroom.”

When a story is published about a Sāmoan taxi driver in Wellington being fired for wearing a lavalava to work, I decide to show my idea of Sāmoan solidarity: I put on a lavalava in the men’s changing room and then walk into the newsroom.

One of the pālagi photographers is amused. “How’d you tie it?” he asks as he lifts the camera up to his eye and prepares to take a photograph of me. I can feel myself blush.

“Safety pins.”

On one level nothing has changed since that photograph Mum took of me in 1977, although this time I have elected to put my Sāmoan-ness on myself rather than being told to wear it.

The photographer looks disappointed. He puts his camera down. Doesn’t take the photo of me in my lavalava. Maybe he thinks the exact same thing I am thinking in that moment: Bad Sāmoan.

It is ironic that I eventually chose to embrace my Sāmoan heritage, given that my father left my pālagi mother to do the hard yards by herself. And yet, on reflection, it makes a certain sense. I had a lifetime of being Othered, with variations of “Where are you from?” from curious pālagi, and then the ubiquitous (but misguided) follow-up once I revealed my Sāmoan heritage: “Do you go back?”

Well, yes, I went to Sāmoa for the first time just before I turned 12, but I wasn’t going back. I was going. And the highlight was not getting in touch with my roots; instead it was reading Sidney Sheldon’s thoroughly filthy potboiler Bloodline, which contained roots of an altogether different kind.

I had a lifetime of being Othered, with variations of “Where are you from?” from curious pālagi

Ultimately, my upbringing was the reasonably common (though not entirely universal) afakasi story of the outsider: Too brown for the whities, two white for the brownies; both sides ready to tell you what you were and, more to the point, what you were not.

My father was an absolutist. He didn’t believe in the concept of being half-caste (a term I myself no longer use, even though I still sometimes employ its Sāmoan transliteration).

“You’re either one or the other,” my father insisted back in the 80s when we first began to dance around each other, trying to establish something that resembled a relationship.

Was he right, all those years ago? Do those of us who are mixed race need to choose one side over the other?

Too brown for the whities, two white for the brownies; both sides ready to tell you what you were and, more to the point, what you were not

I’m never entirely sure when to tulou or not to tulou. About all I can say in Sāmoan is “Thank you”, “Where’s the sapasui?” and “Do you want to sleep with me?” There are moments when I’m not sure how to be.

And yet there I was in a bar in São Paulo in 2009, crying as I watched the devastation of the tsunami in Sāmoa. And, once again, I didn’t have the language to explain how I felt. But I knew how I felt in that moment: Sāmoan, hard.

*

I’m still one of those Sāmoans whose heart begins to beat with fear when that song comes on – you know the one? The one that means you’re gonna have to get up and aiuli your cousin/mate/relative/whoever when they’re up there doing a siva. When you’re gonna have to try and pretend you’re swaying unselfconsciously to the music even while everyone else looks so free and you feel like a self-conscious un-co with arms of lead.

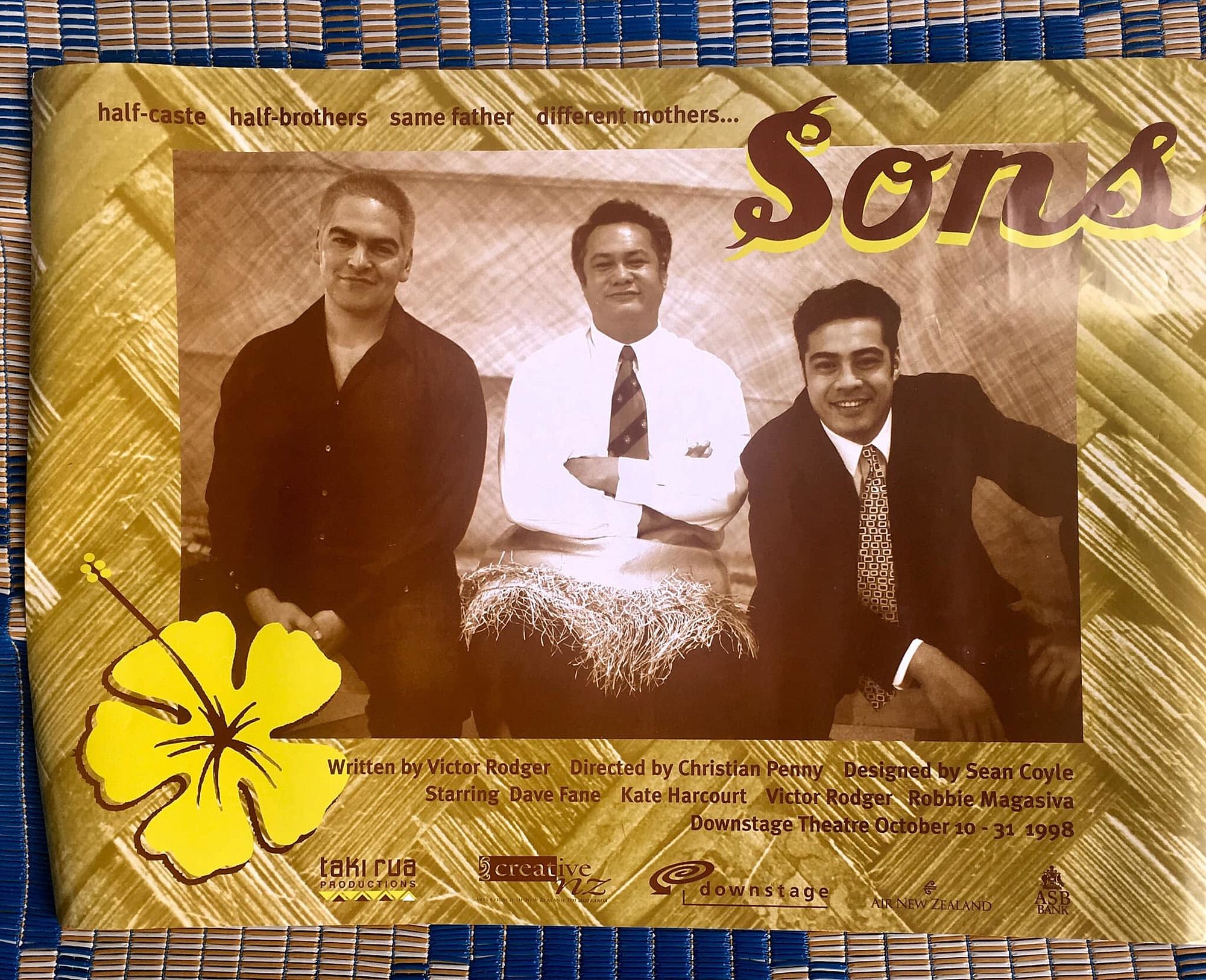

It’s all there, in my first play SONS.

I wrote it in 1994, partly driven to represent my specific part of the Sāmoan spectrum, the part that has no language, no knowledge and yet a desire to belong.

The main character in SONS is Noah, a young afakasi Sāmoan–pālagi who has no clue about his Sāmoan heritage. His half-brother Lua is aware of this (but unaware that they are half-brothers). He ropes Noah into doing a dance at a Sāmoan fundraiser. It’s a set-up: to get one up over the clueless afakasi. Noah dances, despite his reservations. He’s terrible.

The scene is played for comedy.

*

On the opening night of SONS in Christchurch in 1995, the MC called me onto the stage after the play finished. Not to take a bow. But to dance.

And so there I was, dancing, in utter silence. My auntie Leitu‘u got up to aiuli me. Everyone else in the audience just sat there and watched, in a yawning uncomfortable silence that felt like it went on forever.

Life imitated art.

And it fucking sucked.

But, as I have come to learn, it’s all just a part of the journey. Where bits of it really fucking suck. But those bits are far outweighed by the other bits.

For years my rallying cry has been that my face, and others like it, may not be the face of Sāmoa but that we all are a face of Sāmoa. Some of us love Jesus. Some of us couldn’t give us a shit. Some of us feel the fear when it’s time to siva. Some of us feel free and don’t give it a second thought.

My face, and others like it, may not be the face of Sāmoa but that we all are a face of Sāmoa

Some of us end up writing plays that deal with racism in New Zealand (Ranterstantrum) or about being gay (Black Faggot) or that skewer Pasifika academics, politicians and ministers (Uma Lava). FYI, my favourite line from that play is “fuck you and your fucking vā.”

Clearly, I didn’t grow up and become that good little Sāmoan boy that my mother dressed up in a lavalava all those years ago.

But through my work, where I have consciously tried to broaden the spectrum of situations and characters presented within the Pasifika canon – I have, in my own way, embraced being a tama Sāmoa – a son of Sāmoa.

I couldn’t imagine my life any other way.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photograph Edith Amituanai