Global Visions of Unstable Futures at The 5th Auckland Triennial

The 5th Auckland Triennial brings us representations of the real, the unfinished and the performative. Richard Shepherd takes us on a guided tour of his favourite pieces in the show.

Auckland’s 5th Triennial opened a few weeks ago with the title ‘If you were to live here…’. CNN-sounding name notwithstanding, the curatorial premise of the show is to give an account of the experience of locality in an interconnected and unstable world. With only a sprinkling of artists from Europe, the majority on show live and work around the Pacific Rim, circling from the Far East to Singapore, Australia and New Zealand to Brazil, Central and North America. This selection of artists positions Auckland in a new assembly line of economic and cultural exchange as it resists the Trans-Atlantic hegemony. In this way, these art events expose a key desire of contemporary art: to not only represent the world, but to reveal its active part in its ideological and material construction.

The world today is characterised by an unprecedented circulation and movement of people, of capital, of ideas and images. The terrible paradox is that the mechanisms that accelerate this circulation and those that attempt to slow it down or bank it in the Caymans can be violent and destructive. Globalisation isn't some abstract, ethereal process. It involves material on-the-ground events. That greasy feeling in your mouth after a Quarter Pounder is the mouthfeel of globalisation.

These giant global exhibitions are two things at once. They are a symptom of globalisation and they take globalisation as its primary subject matter. They have spread to over 100 events across the globe: Seoul, Shanghai, Havana, New York, Sao Paulo, Bucharest, Berlin, Sharjah, Sydney, Marrakech, Johannesburg and on and on. In 2012, 620,000 people went to the Gwangju Biennale and it's a city of 1.4 million people. But big numbers aren’t the point. Their significance, and contemporary art's in general, is that they can make this process visible. Artworks can show us where abstractions become crushingly real. They show us the form life takes under the heat and pressure of history.

In the 21st century, progressive politics – and a good deal of science-fiction - knows that there is no more land far, far away. “Over there” does not exist. There is only here, everywhere. The Triennial tries to give us a pulse-reading, a map, of this kind of thinking. For the most part it is not a pretty picture. In ‘If you were to live here…’ the iconography of accelerated travel, exchange, conflict zones and diversity that have marked earlier international exhibitions has been suspended by something more cautious and slow. Exhaustion and survival rule the day. Art in the age of austerity maybe?

Black Moon, by American artist Amie Siegel is staged on location in California and Florida at foreclosed housing developments built with “speculative fever” during the US’s massive housing bubble of the 00s. It begins with a group of young women in army fatigues and automatic weapons arriving at what appears to be an abandoned town after descending from the nearby hills. Long tracking shots reveal the familiar image of standardized suburban housing. Some buildings seem only half-finished. Everything is coated with red-brick dust. The whole scenario speaks to a Ballardian landscape of blight and exhaustion. At one point the troupe of would-be revolutionaries take shelter from the desert heat in an empty swimming pool surrounded by the browning grass and fallen palm tree leaves. One woman pathetically clutches a hose that extends out of frame, perhaps in some gesture of remembered intimacy.

Showing at the Gus Fisher gallery is Albanian artist Anri Sala’s video The Long Sorrow. Although the title does have a noirish ring to it, it’s much less reliant on film history and cinematic narrative than Siegel’s contributions, though architecture is still a central focus. The piece is named for the building it takes place in: the lange jammer, a high-rise apartment building in Berlin near where the wall used to be, named by its own inhabitants. It was built in the 1970s in the German Democratic Republic and is part of a larger complex of mass social housing, that Judas of modernist architecture.

The film begins inside a small, bare apartment facing outwards at a window and is projected in the gallery at more or less 1:1 scale. The frame is static and we can hear traffic sounds, voices and most clearly a jazz saxophone. There is something on or just outside the windowsill that is difficult to discern (Sala loves showing how little we see). After several minutes the camera zooms very slowly towards the window but the effect is one of the window approaching you. Bells start chiming and the music responds in plaintive tones. The set-up is revealed and we realise that the indiscernible object is the back of free-jazz musician Jemeel Moondoc’s head; he is suspended outside the window of the 18th story. The camera travels outside and meets Moondoc in an extreme close-up of his face, eyes closed, fully absorbed in a trancelike mimicry of his environment.

In Kirby Dick’s film portrait of Derrida, the philosopher speaks of the myth of Narcissus and Echo. Echo is cursed by the Gods to only repeat the fragments of her beloved’s speech who famously gets distracted by his own reflection. But for Derrida, Echo is “loving and infinitely clever” and through her repetition claims his words for herself. He says, “In repeating the language of another, she signs her own love.” The film (including one’s experience of it) seems to embody the conditions of both Narcissus, absorbed in an inner world, and Echo, singing her love song, barred from each other. This reading seems confirmed by the final few images of The Long Sorrow. Moondoc disappears but his music remains, lingering over a wide-angle panorama of the whole housing complex in a potent sign of loss and failed promises.

*

In the adjacent room we encounter another door entrance, this time as video projection. Nothing moves in the frame except for a gentle swaying of branches hanging above a door that is set in a heavy black stone wall. The image would be reminiscent of live-feed surveillance, were it not for the camera’s ground-level positioning, directly in front of the door, as if waiting for something to emerge from it. The wall text for the piece, The Most Difficult Problem, informs us that the door is actually the entrance to a set of WWII tunnels dug under Albert Park, the western edge of which directly connects with the Auckland Art Gallery and the room Maddie Leach’s work is installed in. There is a small text provided on a bench which reads as an early 20th-century newspaper article about the splendours of the New Zealand glowworm that the writer had experienced up an “old drive”. Albert Park or the tunnels are not mentioned. Playing on loop in the room is piano music from an operetta composed by Paul Lincke (we read that he was “honoured” by the Nazis in 1937). The tune, ‘The Glow Worm’, was made famous in post-War America by a jazzed up version by Johnny Mercer (who wrote, among other things, the words to ‘Moon River’). The swarm of references does not diminish what is actually a sparse, minimalist experience, tinted by the sweetened nostalgia of the music. Leach seems to want to build some imaginative experience of distance into an object that is literally right next door.

*

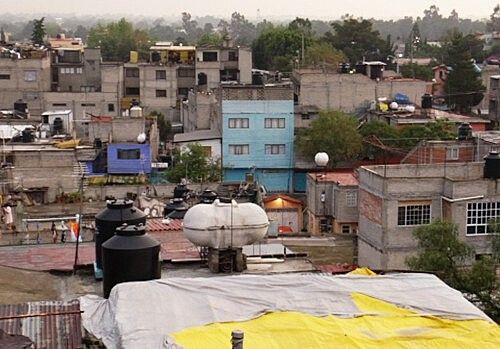

Jacques Rivette once claimed that every film is a documentary of its own making. Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas has made a film titled Autoconstrucción (literally self-construction). It’s part of a much larger suite of projects that include small assemblage objects made from found materials, music and books. The artist has described it as a kind of “slow sculpture” both in form and its subject matter. The film is composed of a series of static long takes that depict the artist’s hometown of Ajusco, near Mexico City. The town has a history of squatting and occupation by families and migrant workers going back to the 1960s. The camera lingers on the sites of improvised construction, not just dwellings but the various accumulations of involuntary invention that come with actively-used shared spaces. Interspersed with these images are unsimulated sex-scenes (only heterosexual couples of various ages in the excerpt I saw, though the full film is 62 minutes long) shot on location in the bedrooms and rooftops of Ajusco.

The detached style and everydayness of it diminishes the sense of seeing something subversive or outré. But it is one of the very few works in the Triennial that has a direct erotic element. Viewing the long take can be a transformative experience. After-images of sexual encounters, the free (if often clumsy) movements of desire superimpose on scenes of a cluster of sagging bricks. The desire for everything real, raw and unsimulated could be seen as a response to the widespread feeling of inauthenticity produced under a global commodity logic. Autoconsctrucción, of course proposes nothing less “constructed” and its communal ethos of means-over-ends looks exhausted and, as the town sits atop a volcanic landscape, unstable. Behind this image of spontaneity and survival is REDCAT, a commissioning body housed in L.A.’s Walt Disney Concert Hall.

Photographers Yto Barrada and Bruno Serralongue are exhibiting works at Artspace on K’rd. Barrada’s images from her native Tangiers juxtapose children at play in domestic settings with images of the half-finished and unfinished built environment that is the Triennial’s signature. Modernity is indeed an unfinished project. The suite of photos on display seem to be awkwardly removed out of larger bodies of work and it is difficult to piece together a cohesive atmosphere from what we get to see. Serralongue ‘s images are all taken from a long-term project based in Kosovo that will document that nation during its first ten years of independence. Like Barrada, Serralongue produces images against the flow of clichés that cohere in other media streams. For Kosovo it is the time of fragile rebuilding. Serralongue is drawn to small-scale economies on the street but also signs of incorporation into the global fabric. A photograph outside a conference room carries the signatures of Rockefeller and Soros.

*

Many of these ‘documentary’ works include an important performative element. Black Moon ends with a wonderful uncanny moment where one of the troupe (who are all styled and cast as if for a runway event) finds a high-street magazine in the desert surrounding the gutted housing. Flicking through it she is shocked to discover a feature section titled ‘Revolutionary Chic’ that features the members of the militia, including herself, as fashion models [1].The film proposes that this crisis (and capital in general) is always already ahead of any critique that traffics in clichés. In Siegel’s Winter a young pale-skinned girl with tight red curls speaks te reo Māori over an imagined presence as if communicating with past loved ones. This short sequence serves as a utopian response to the antagonisms present in Luke Willis Thompson’s Untitled. The participants in Autoconstrucción are not from the area and were hired from classified ads placed in Mexico and Los Angeles. It is worthwhile seeing them as workers as well as ‘performers’. Much like in the pornography industry that the film quotes, they earn a wage and produce value. We are waiting, after all, for the money shot.

Jonathan Beller, in The Cinematic Mode of Production, argues that the worldwide production, circulation and consumption of commodities and images (which today are the same thing) follows a cinematic logic. Digital technology has brought “the industrial revolution to the eye” and today “to look is to labor” [2]. We are all now engaged in various kinds of screen-work that demands our attention in every intimate and ultimate sphere of life. Which is all to say that we the audience are performing too. We circulate from screen to screen for our pleasures and unpleasures, or perhaps just for a whiff of gossip by the wall-text. The spectacle makes the audience as once Ford made cars.

But unlike the captive audience of individuals in the cinema-factory, the audience in the exhibition and the ‘social factory’ at large is mobile, reflexive, chatty. The visual and semiotic composing of things, of ourselves, of worlds is now – at least in the over-developed West – the dominant form of productive labour under the neoliberal model. Power will try to cloak itself in invisibility, in immateriality, by annexing the qualities of openness and autonomy. The Triennial’s focus on embodied performances embedded in impersonal social forces and abstract economic ‘flows’ enables us to feel a sense of this, even as it constructs us as witness and co-worker.

*

For me, two of the most crucial works in the Triennial where many of these themes come together are Allan Sekula and Noel Burch’s film essay The Forgotten Space (showing at the Film Archive) and Ryoji Ikeda’s sound installation A [for 6 silos] at Silo Park on Auckland’s recently developed waterfront. If, for Beller, value is produced in the blink of an eye and, like Eric Packer in Cosmopolis, we are speculating into the void, the forgotten space of globalization is the sea. Sekula and Burch’s film reminds us that 90% of the world’s cargo still travels by sea on enormous ships staffed mostly by workers from the developing world. This labour is largely absent from the heated discussions over the instantaneous and ‘imaginary’ money trades that are meant to characterise our economy.

One of the reasons for this is due to ‘containerisation’. Sekula’s narration describes the container as the “acme of order…anonymous, odourless, abstract”. This contradiction of ubiquity and invisibility is beautifully illustrated by an image of a container stack’s shadow cast on the motile ocean waves. The sun passes behind clouds and the shadow pulses in and out of sight. All the liquidity in the world does not diminish the homogenous dimensions of the container. The film focuses on the recent histories of four major port cities: Rotterdam, Los Angeles, Hong Kong and Bilbao, and conducts interviews with workers, managers and port authorities. One man, working as a crane operator 30 meters up at the Rotterdam port, spends his shift looking straight down through a small window four of five feet in width. The strain on his eyes, his whole body and concentration is such that shifts cannot last more than four hours. Increasingly, however, these kinds of jobs are being made obsolete by automated machinery that can work 24 hours a day. Such is the fate of Bilbao where de-industrialisation accelerated by shifts to cheaper labour markets elsewhere has seen a rapid decline in its maritime activities since the 1980s. In its place are the shimmering icons of the “new economy”: gentrification and cultural tourism.

Which leads us to Ikeda’s site-specific installation in Silo Park at Wynard Quarter. As a place that has been purpose-built to host events covered by the international media, it has been botoxed to conform to international media standards. Its website informs us that it is situated on reclaimed harbour land and was once a primary site for the storage of petro-chemicals. The six silos were used as cement stores and the website boasts that a substantial amount of the city’s foundations were once housed in their cylinders. Today, the area’s industrial past has been transformed into the same promenade of chic restaurants, condo-style apartments and marinas that litter cities all over the world. Ikeda has installed six modestly-sized speakers in each concrete cylinder that produce a sustained ‘A’ tone (the concert pitch used to tune musical instruments) that reverberates in the hollowed out structures. Each speaker plays dozens of tiny variations in frequency of the concert pitch that are taken from its almost 300 year-old history. Today, it’s defined by the ominous-sounding International Organization for Standardization as 440Hz. The piece mimics the relic it’s housed in and is a kind of living fossil that traces the outlines of its own history. 440Hz is also the frequency of the telephone dial tone (remember those?). I imagined the silos becoming a complex of radio beacons, sensitizing the concrete to some kind of alien signal from a distant future to be bounced off the urinal atop the ASB bank building nearby.

And so we are left with a heightened sense of suspense. Call waiting. Sekula and Burch wonder if the container is a Trojan horse that has turned on its masters. The works in the exhibition are full of these broken promises and heralds of disasters come to roost. But amongst the ruins there is also the expertise of everyday life; its pleasures and inventions. No one might be able to imagine a different future but there are signs that survival might not be the only order of the day.

[1] The spread was made on commission for the film by Eden Batki and can be viewed at the website http://www.edenbatki.com/Black-Moon

[2] Beller, The Cinematic Mode of Production: Attention Economy and the Society of the Spectacle. Dartmouth College Press: 2006, p.2, p.9