Glitches & Sweat: A Response to Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa

An overture of bodies, movement and feels, Amit Noy reviews Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa.

Here is a body, deluged by a flood of their own sweat. They methodically collect their liquid efforts with the slit of a Mastercard, for deposition (taptaptap) in a measuring cup. Here is another body, slouched nude in a bathtub, surrounded by an abundance of brightly coloured wool. They knit with slashing needles and lecture blithely on “slut money”. Here is a third body. This body goes by Harold, and they perform through the Zoom-verse. Harold is a potted plant. Harold, a co-performer explains, is a little shy.

These are some of the bodies of performers I saw at Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa, a five-day festival that took place from 1–6 December at the Herald Theatre in Tāmaki Makaurau. There were panel discussions, workshops, a slew of performances, and (of course) miles of foyer chit-chat. The festival, founded and curated by Artistic Director Alexa Wilson, included 19 artists from Aotearoa and Australia. All the artists offered generous and individual projects. After five days, I left feeling the cumulative effect of gentle expansion. Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa and its artists activated the dynamic field of possibility that lives, however deviantly, under the sign of ‘experimental dance’.

‘Experimental’ requires a certain unknowing, a process of getting lost. We can think of ‘experimental’ as a fugitive disidentification with the proper and the placed. The artists of Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa collectively opposed the staid enclosure of certainty. Instead, they staged performances that were open questions and conversations, embedded with acrimonious critique and tender scenes of pleasure.

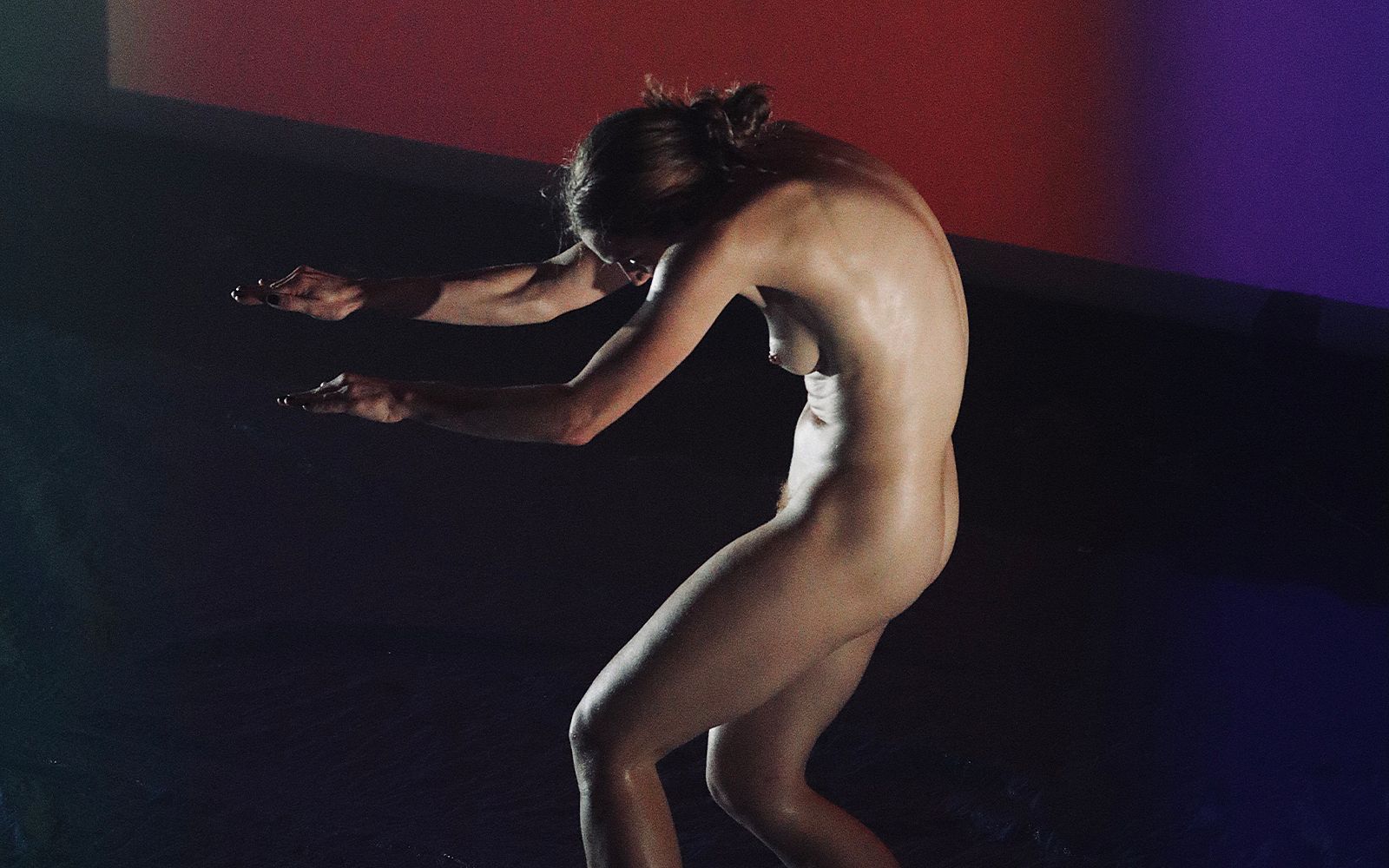

Oliving McGregor in Performing Object I

Two solo performances engaged differently with the ongoing question of wearing clothes. In David Huggins’ Performing Object I, Olivia McGregor performed a micro-dance enveloped by many plastic picnic stools (the cheap, foldable kind you buy at the Warehouse, ideal for languorous campouts at the beach on hot summer days). Olivia lay on their side with their back to us, and alluded to movement: slight twitches of the feet and fingers, a quick gliding motion of the scapula. Notice the curve of the torso like a flat hill. Notice the matter of their naked body, co-present with the picnic chairs.

I feel a bathetic tenderness in the reclining body of Performing Object I, like Laura Aguilar’s self-portraits in the barren outskirts of Long Beach. When McGregor, still entangled, stands up, I sense their body as scaffolding, and I attend to their collaboration with the chairs, and the quiet strain of their metal bolts, who hold it all together. I move with Performing Object I in a different experience of relation, where thoughts drip into me as ice thaws.

As some bodies collapse into kinetic lack, others sprint towards violent surfeit. Katrina Bastian’s Soliloquy in Sweat drives perversely towards the expulsion of bodily fluid to the untzzz untzzzz of indefatigable techno, and a 20-minute ticking countdown. Sheathed in a plastic suit, she moves with spider violence through a choreography of vicious gesture and hurling-leg virtuosity. Bastian works to produce as much sweat as she can, and in doing so, she gives us the opportunity to observe the material labour its production demands.

Katrina Bastian in a Soliloquy of Sweat

Who can afford to become a dancer? Bastian performs to further ensnare herself in the twin rhythms of money and sweat, a labour economy whose principle Paul B. Preciado names “the compulsive reproduction of the excitation–frustration cycle to the point of achieving the total destruction of the ecosystem.” It’s scathing, embodied ‘institutional critique’, staged in conversation with those who popularised the form in the visual art world – Andrea Fraser, Hans Haacke, and others. As Bastian collects her excretions with a credit card, and squeezes sweat from the cling film that had been wrapped around her torso, I watch it dribble into the measuring cup. Soliloquy of Sweat sets forth sweat as the material currency of dance work – an ephemeral, often exploitative labour economy.

I peer into the cup post show (it’s left onstage) and see globs of congealment, akin to sour milk or semen. The opaline stuff stands as the fetish object of dance’s ableist obsession with hard work and impressive physical feats as a requisite to any claims of value or legitimacy.

Failure is a counter, a strategy for another way: “It quietly loses, and in losing it imagines other goals for life, for love, for art, and for being.” val smith’s quietly epic i’ll grow back was performed by val smith, Naarm-based artist Forest Vicky Kapo via Zoom, and their collection of plant life, present digitally and onstage. The performance lived multiply: val smith ‘live’ onstage, Forest Kapo Zooming in on an iPad, and their cohabitation in a Facebook livestream displayed on a floor-to-ceiling projector. (The livestream is still available on the Facebook event page; I recommend it.) Kapo and smith spoke to each other, about gender and embodiment and –

“Are you happy with your body? The one that you’re in?”

“I am…. Complicated.”

“Are you performing?”

“In theory, yeah.”

“I feel a really strong urge to hide right now.”

“The passionfruit isn’t so happy with their role tonight.”

The livestream glitched, like they always do. I felt a keen sense of loss listening to Kapo’s voice disconnected from their moving Zoom body, and witnessing smith’s existence queerly doubled, their screen presence always reflecting their actions 20 seconds ago.

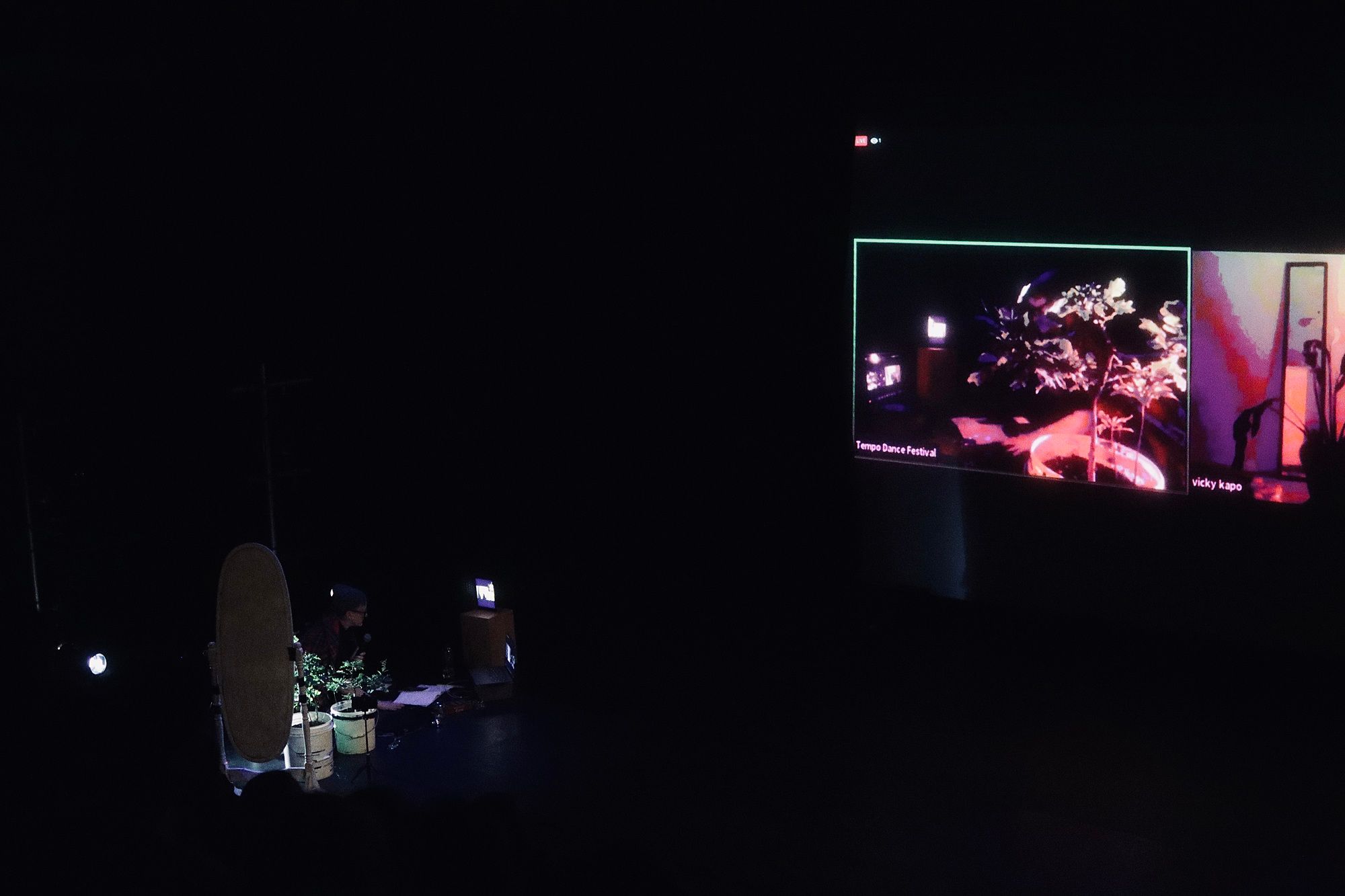

val smith's I'll Grow Back

Glitches are tiny, precise cuts. They leech on the myth of “straight time” to make space for queer, trans-generative openings. Their hiccups index “the world’s ongoing refiguring”. Kapo and smith dived around the singularity of live performance, choosing instead to swim in the ensemble of affect we call the internet. Liveness and presence became a general field of multiple feelings, like the many appendages of a starfish.

We were floating in a sea of empathy. Drawing tarot cards and conducting readings for their plant companions and each other, Kapo and smith mapped a non-anthropocentric kinship, in which we were “not human alone, but human with many.”

Body island. Body is land. Body, I land. Kelly Nash’s Body I(s)land, performed by Kelly Nash, Nancy Wijohn, Daniel Cooper, and Rosie Tapsell (with sound by Rowan Pierce), stemmed from their collective practice of ConTact C.A.R.E., a bodywork method founded by Dale Speedy focusing on a constant “moving away from pain”.

Body I(s)land tracks how we land in our bodies, in moments that limn death and quiet bliss. Throughout the performance, a screen in the upstage left corner showed slow-motion footage of people careening down hills in cheese-rolling competitions, airborne babies caught after being thrown out of burning buildings, and strange, engrossing shots of reclining horses and AA batteries. I watched an astronaut work through the gentle bloat of gravity on the moon, and I thought of my body (never not dancing) as what Deborah Hay calls a “spewing multidimensional reconfiguring nonlinear embodiment of potentiality”.

Kelly Nash's Body I(s)land

Co-present with the video, live performers sketched the contours of their own sensual curiosity in questing dances of perception. They vibrated their kidneys, wrapped themselves in foam hands and rolled across the floor, and wrestled with a tightly sealed jar of pickles. A voiceover asked us to consider the absurdity of the whole ‘I’ in favour of the innumerable I/eyes of our anatomical existence: the ‘I’ of my left patella, or the ‘eye’ of the soles of my feet. All my innumerable ‘I/eyes’ loved this dance.

The afterglow of performance is a gossamer field of wayward, unreliable memories. It’s made-of-life status makes it difficult to catch. We might, following Fred Moten, say: “some [performances] want to run things, other [performances] want to run.” Some views from the week that have yet to escape: Joanne Hobern and Jazmine Rose Phillips in Magnificent Violent Sparkles,dancing a torpid, banana-slug duet amidst the residue of a brawl with two heads of lettuce. When they slid across the shards of leaf on the floor, their flesh squeaked. Rebecca Jensen’s video animation in The Effect, of her skin cascading into emptiness, the matter of her face rising and falling in playful ribbons. Virginia Kennard in Disssordered Deficit of Active Attention, walking her half-dozen skeins of yarn like dogs on leashes. There were others, too many to name.

I leave Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa with gratitude and respect for the artists’ intelligent courage. Alexa Wilson curated a festival that blossomed with difference. It was a joy to see such care and respect given to dance and performance by artists and audiences.

Thank you for your gifts. In a pandemic, to be together in a black box is a quiet miracle.

Feature image: Virginia Kennard in Disssordered Deficit of Active Attention. All images courtesy of Courtney Rodgers.