Getting Comfortable

On bringing more of ourselves into our art spaces, curator and artist Siân Torrington in conversation with Maungarongo Te Kawa and Zoe Thompson-Moore.

My mum taught me to make bread and to sew. We did both on the kitchen table, the one that’s in my kitchen now. I’ve never thought of these things as art, but part of life. Part of the support system of being an artist. I can fix my clothes, alter them and make more. I can live on less – so I get time to make things. Craft is often taught or shared in intimate ways – passed down through generations and woven with stories and connection. Is it ok to talk about love and care in the same breath as ‘gallery’ or ‘art’? Is it ok to need warmth, encouragement and blessings as you learn in these spaces?

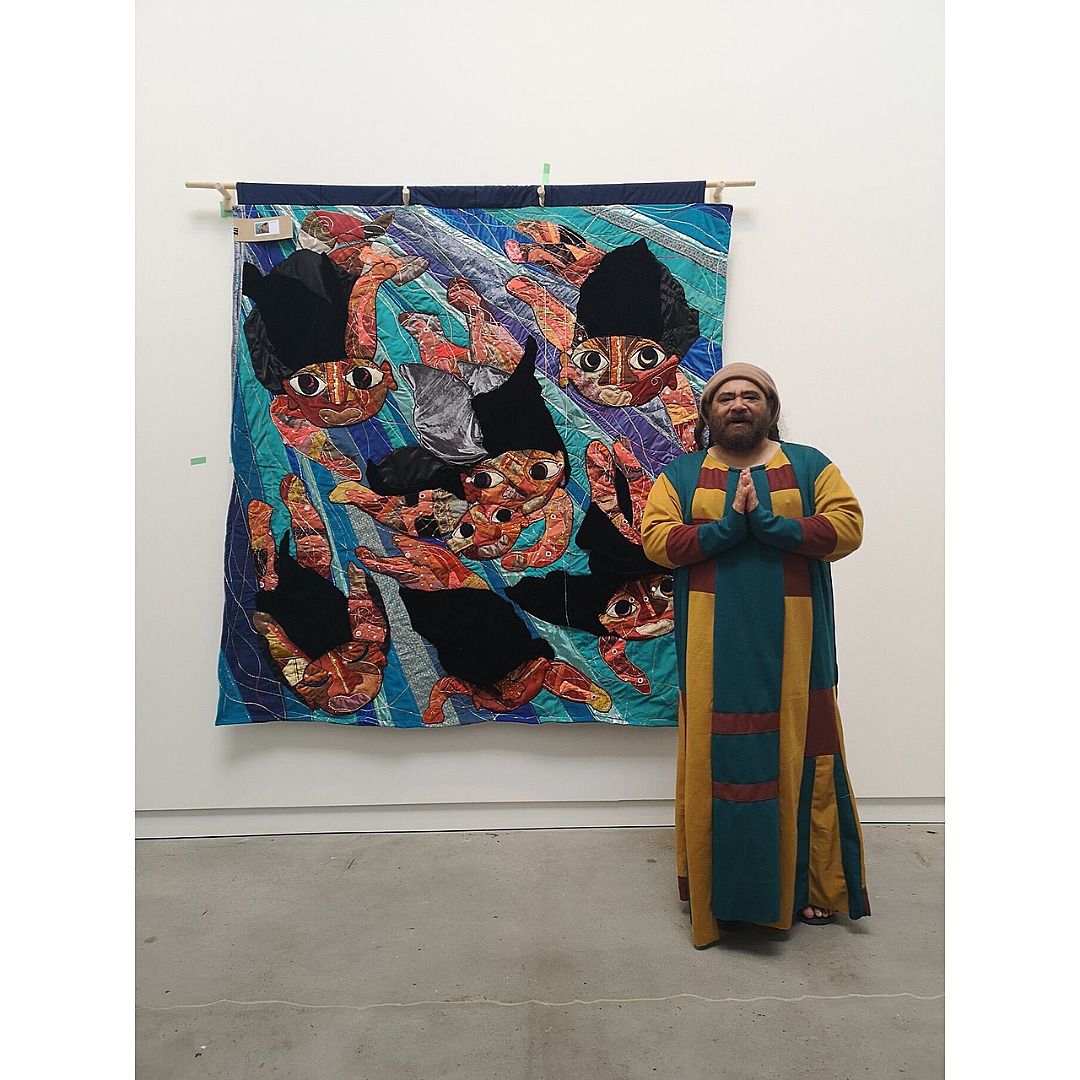

Maungarongo Te Kawa

Maungarongo (Ron) Te Kawa (Ngāti Porou) is a fabric artist, storyteller, quilter and fashion designer. He uses a multitude of fabrics and materials to create his distinctive narrative works and unique practice of workshopping personal stories into whakapapa quilts. As an artist, teacher and guide for others, Maungarongo is an expert at holding spaces for people to learn and create without judgement.

He has exhibited his work extensively, most recently at the Centre of Contemporary Art Toi Moroki (CoCA), Christchurch, Objectspace, Auckland, and Te Kōputu a te whanga a Toi, Whakatāne. He was awarded Best Futuristic Design at the 2006 Canterbury Fashion Awards and nominated for a Benson and Hedges Fashion Award. In 2019 he was also named the Adult Community and Education Aotearoa Māori Educator of the Year.

Maungarongo generously shared with me about the kaupapa of his practice, and what sustains him and others.

Zoe Thompson-Moore

Zoe Thompson-Moore uses practices and materials that relate to the everyday, such as bread, potato peelings and wool. By collaborating with others in making her work, she explores the relationships between creative work, and work in and for a household. She folds relationships with neighbours and galleries into processes of making, providing and sharing. Her art practice questions the relentless production required by capitalism, valuing instead community and processes that take place in their own time.

Zoe has exhibited most recently in From the Ground Up: Community, Cultivation and Commensality at The Dowse Art Museum. Her ongoing bread project,The making of bread, etc., with Enjoy Gallery, is documented in As needed, as possible: Emerging discussions on art, labour and collaboration in Aotearoa.

We first met over bread making as part of her project. When she sent me the image she took of my hands making bread, I saw my mother’s hands. Kneading, strong and capable, fast and sure, able to feed you. I use what my mother taught me to build sculptures. That soft is stronger than hard – binding, weaving and sewing pieces together until they can be as big as a building and last for months in the snow, outside, as strong as love.

What happens when the methods and histories of craft meet art and galleries? How do they transform and challenge each other? What might need to change for them to sit in comfort together?

*************************************

Siân Torrington: So Maungarongo, you’re talking to us from your home – where are you?

Maungarongo Te Kawa: I’m in a little town called Woodville, population 1200. I grew up here; my parents built the marae and are buried here. They are Ngāti Porou and moved here for work, a railway workers’ town. We’ve got a papakāinga, and I’ve got over 50 cousins here. It’s my turangawaewae, my home. I’m on Kahungunu and Rangitāne land, so I pay them big respect. I’m totally grounded here, in my dad’s old studio. I’ve got all sorts of permissions: to be messy, have tools everywhere, sleep here, have family, to make a garden out the side window. He fixed cars, built things in here, and it’s still got that energy. There’s a connection between him and me; it's special. I’m the youngest in my family. I’ve got permission to be the pōtiki, the fun one, the questioning one, and the one that picks up the baton from the generation before.

ST: How do you describe how you work with others, running workshops?

MT: It always starts with grounding. I let [the participants] know that I see them as whole beings; spiritual, emotional and physical. And I bring them to different spaces. The exhibition at CoCA in Christchurch was called Hīnātore. For six nights of the year, the Matariki sisters dive into the ocean, they go into a different world of soft light, phosphorescence, gentleness and rejuvenation.

For the workshops, we create space for ourselves, internally and externally. The tohunga, priests and priestesses who would have held sacred spaces like these, are all gone. We start by sharing our pepeha in a circle and talk about the energy we’ve brought in; our lives and expectations. When everyone has spoken, I know which kind of space or energy I need to call on. We make craft, but it’s more about the process than the finished product. I want them to take home the ability to make a creative sacred space that lets them connect with their ancestors and different positive energies.

We start by sharing our pepeha in a circle and talk about the energy we’ve brought in

I work with three basic principles [in my crafting]. Te Whare Pora is knowledge gifted to me from the weavers, and I pay homage to them. I see what I do as an extension of weaving rather than an extension of quilting. Back in the old days (this is how my tutor at Papaioea, Amy Kuru, described it to me), when a baby was born, the old people would watch that baby. When they knew it was a weaver, artist or poet, they would build a structure, a physical house, inside the compound called Te Whare Pora. So pō is night, rā is day; it’s the energy between male and female, black and white, yin yang. It’s the creative zone beyond our physical experiences of this world. I hold that spiritual space for the group, so they can be the voice for their creativity.

There are different ways of holding that space; naming it, chanting, writing about it. It’s actually a lived experience; this is what keeps me sane and rejuvenated. Creativity is a conduit, a way of chucking up those sacred walls and saying, “Right now, it’s all about me.” And then the magic starts to flow.

We connect with Hine-Te-Iwaiwa, the full, bright, white moon, the energy for midwives, poets, fabric artists and weavers. She’s the energy of growth, a millionth of a second before a flower pops open. This knowledge was gifted to me at the Indigenous Midwives Annual Conference to pass on through quilting. I always have kōrari stalks holding up my quilts; they’re a tribute, as I am a servant of hers. Her repeating patterns are my maths and algebra, a reflection and symmetry that’s bigger than us.

The midwives still sing to Hine-Te-Iwaiwa, chanting as the baby is born to bring the water forward and the baby out. She’s that big, fat, gorgeous energy that just keeps filling our soul, no matter what.

Fabric art softens people’s stories. It’s easier to access harder stories like family trauma, pain or grief through the tactile

A lot of those who come to my workshops are traumatised by school. When one culture wants to rule another, they’ll put in one royal family, one religion, one set of weights and measurements; but I tell my students, if our Egyptian whānau could build the pyramids without imperial measurements, we’re going to be fine.

The third one I use is Waipuna-ā-rangi, and that’s personal to me. I never get a block; I never run out of energy or ideas. So when students have a mental, emotional, spiritual block, I get them to close their eyes and call in someone from one generation ago who loves them unconditionally and ask them to put their hands on their shoulders. It’s a good opportunity for people to rewrite their whakapapa. It doesn’t have to be someone related to you. Go back, keep asking, create a line of champions for your fabulosity and imagine them in their finest kākahu. This line that goes for kilometres, right back before the Big Bang and galaxies, to Waipuna-ā-rangi, which is a pond full of all the good things we could ever want and need. All we have to do is turn up and ask, and it will be passed down to us through that beautiful river of whakapapa. So it’s also about making people’s “yes” bigger. It’s making the ask bigger.

So Te Whare Pora, Hine-Te-Iwaiwa and Waipuna-ā-rangi, that is what I’m there to share. It’s not about who will make the best quilt, or who’s done the most perfect sewing. That just totally bores me. We don’t just do a quilt with our pepeha, mountain, river, sky and meeting house. We pull in the beauty and mauri of the maunga, the smells, colours, flowers and sparkles. Dive into your river; what does she have to say to you? Nine out of ten times, it’s “Look after me.” When you hang up your quilt, all your moko, family and visitors should feel your love for your maunga and your responsibility for your awa. It’s not just a pretty picture, and it’s a different way of seeing the land.

Fabric art softens people’s stories. It’s easier to access harder stories like family trauma, pain or grief through our fingers, the tactile. My idea of a whakapapa quilt is a story that you can wrap somebody in, like aroha.

In a gallery there’s often one person championing you, and the people behind them are unsure

ST: Recently, you’ve been bringing these spaces into galleries – how do you warm them up?

MT: No two places are the same. Some are warmed up already; people are excited to see you. But it depends on who’s brought you there and why. Quite often, I get asked into a space to change the culture. They don’t tell me that; I figure it out halfway through, and that was really hard at the beginning. You just have to be as authentic as you can. Go in there with pure intentions, and nothing can move you. In a gallery there’s often one person championing you, and the people behind them are unsure.

As a Māori man, Gay, socialist, fat, you’re always being auditioned. Not just in art galleries but in life. You’re constantly being monitored – are you going to stuff it up? That’s how it is for our boys, teenagers, our men. We can be what we want to be on the rugby field, in the army, but you can’t be yourself on the street because it’s dangerous. So I try to reward the person that’s taken the risk to get you in there. If you stuff it up it could affect the next ten or 20 years of that gallery’s relationships with Māori artists. So it’s about giving. So little of it is about the end product.

I see art galleries as places that were never, ever designed for people like us. Now their doors are wide open, but there’s still a hangover. And why should they change? Just be honest – this is a white space for white people to talk about white art. Sometimes that’s just refreshing to hear, “This is about me and my experiences as a Pākehā.” You negotiate all the time, looking for the stepping stones across the raging river. Where's the safe spot? Where’s the next step?

I hung the Gay flag, burnt incense, had a Buddha, a Guanyin and a carving

I’ve been lucky to work with some outstanding curators, like Zoe Black and Sarah Hudson, who see me as well as the work, and relate to my process. Māori curators are trying to bring a minority into a majority space and reassure everybody that the world will not fall apart and that people will respond.

When I was in Gisborne and had my little shop, I painted the wall black and wrote a big peace poem in chalk. I got the Green Party newsletters and put them all in the window. I hung the Gay flag, burnt incense, had a Buddha, a Guanyin and a carving. There were about 20 booby traps that people had to go past to get into my shop, so I knew I was safe with whoever came in.

ST: I am just bundling these treasures up and putting them into my kete. Thank you so much for sharing all of this.

*************************************

Zoe Thompson-Moore: Nō Mannin Isle of Mann, nō Ingarangi, nō Aerana, nō Kotarana ōku tūpuna. I whānau mai au i Ōtautahi. Kei Waiwhetū au e noho ana, i raro i te maru o Pukeatua. I’m Zoe, and sometimes I call myself piecewerk when I’m making art. My primary responsibility is as a caregiver, and my kids have been little over the last ten years. Adopting that identity was about finding a way to find time for my creative practice. There’s a history of women supplementing the household income by working on textile-based work at home and getting paid per piece.

ST: The first time we met, we made bread together. I shared the bread my mum taught me as a child, simple everyday bread that rises while you vacuum. She had to reteach me in person as an adult, and stick my finger under the tap to feel the right warmth. That learning through the body was quite intimate.

ZT-M: It felt like an honour every time I spent time with someone at their home, making bread together. I’m sort of still blown away that people were really happy to have me and to share things with me. Their generosity and trust were the foundation of the project.

Zoe Thompson-Moore, The making of bread, etc.

ST: For me, making bread is a simple way to wellness and grounding. I don't know if I would have ever thought of it as art. Where did the project come from?

ZT-M: We live with this myth of scarcity, and I want to generate possibilities with my creative practice. I'm interested in the idea of daily practices that you tend so they can grow and develop. As an artist I’m still finding my way, and asking how it all comes together.

The breadmaking started when somebody at a wānanga I was at caught the sourdough bug. My previous sourdough bug didn’t last because the kids were too little, so I couldn't keep it alive. This time around, I got obsessed. I’d just finished motherload-motherlode (2019), a project where I saved our household waste for six months and then built a compost heap with friends that cooked for another six months. I was interested in this idea of generating something incredibly rich and potent out of nothing.

ST: It’s much easier to be an artist with no one to care for and no dinners to make – the lone genius staying up till two in the morning. I really resonate with what you’re saying about how those relationships of care feed into the practice.

ZT-M: What sustains us was a question posed through The making of bread, etc. My creative practice totally sustains me, and if I’m not attending to it regularly, I’m not very happy, which isn’t good for anyone. I work quite slowly, which can be hard in this fast-paced world. But things just take time. I sometimes feel that I want to work all night or all day creatively. But then people are like, “I’m hungry, Mum.” So there’s discipline involved and pulling myself back.

Zoe Thompson-Moore, motherload-motherlode (2019)

ST: When you say ‘open studio’ – is your home the studio?

ZT-M: Yes. I did a self-directed Artist Residency in Motherhood for a year at home. It was started by an artist called Lenka Clayton. Every Saturday, I went into my studio, aka the spare room, and did something. I’ve got years of exploration out of the stuff that was seeded during that time. In the end, I invited friends and interested people over for an open studio and celebrated what I had done in that year, including giving away the motherload-motherlode compost pile.

What was really great was many people came over that didn’t know me as an artist. They knew me as Zoe from Playcentre or the community garden. I’ve tried to bring all those people along as I’ve continued to make work. The workTo feel with the hand (tickling potatoes) at The Dowse helped me feel safe in the gallery. Before the work even got there, it had already been experienced by a whole community. We’d had conversations through me asking for their potato peelings to make the artwork, and they all came with me.

I sometimes think people didn’t realise they were eating an art project with The making of bread, etc. They were just eating, which was good cause people should be fed when they come to the gallery. And then there were the people who shared their bread recipes with me, my neighbours, and friends at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa who I shared loaves with because I was making ridiculous amounts of bread. All these people were experiencing what I was doing, not necessarily as an art project. We were sharing together and making connections.

Zoe Thompson-Moore, To feel with the hand (tickling potatoes), installation view, The Dowse, 2020. Photo: Ted Whitaker

A big impetus for the bread project was my maternal grandmother, who loved baking bread. She died when I was a baby, but my mum often tells me how similar we are. So that’s been spoken to me all my life. Dad talks about how you’d be in the car to leave after a visit, and she’d run to the vegetable garden to cut you some rhubarb or silverbeet. She wanted to be a scientist, but she had to be a nurse and help on the family farm when her brothers went to war. So I think about her a lot, and other people who’ve influenced me, they’re the people I dedicate my work to.

I think about what it means to have a values-based practice. Values are not outcomes; they’re actions, ways of being in the world. How do I want to be? In a gallery, I think about how I want to be in that space. Am I going to introduce myself to people I don't know? Because it can be so awkward. Galleries are just really awkward spaces sometimes.

Part of the bread project was trying to figure out, could I fit in that space? I realised I had something to give, and there’s a vulnerability when you give a gift. What’s incredible and unanticipated is the relationships it generated with people who wanted to hang out with me in the gallery kitchen. Who ate bread and talked to me about it. Now every time I see them at an opening, there’s something there. It’s kind of sacred.

Galleries are just really awkward spaces sometimes

ST: Yeah it is! That’s what I learned by doing that with you – that this everyday thing was really deep and sacred.

ZT-M: I grew up in church, and although I’m not religious anymore, I've been thinking about the Lord’s prayer a lot lately, “Give us this day, our daily bread.” Yes, it literally says bread, but it’s actually about presence. Today there’s bread in front of us that we’ve got to be with, so let’s pay attention to repeated acts of care and attention. There’s a lot of transactional stuff in the art world, but I aim to be relational in my creative practice. I feel a commitment to all the people I’ve done things with.

Then Enjoy moved into a new space where they had a kitchen, and I could actually make bread there. I tended to make the bread for when they had events happening to support these other artists. People often said, “Oh you’re making bread for us today. Thank you.”

It’s so lovely when people take care of you, and it doesn’t have to be a big thing. To just feel seen. I think the project highlighted the importance of Enjoy hosting in that way, and the need to invest in basics like plates or spoons. They’re a small team running around trying to do all the things, and, actually, these take energy and resources.

That this everyday thing was really deep and sacred

ST: If our values shift, then how we do things has to shift as well, including making time to be in the kitchen. And your work comes out of that, like the beautiful work made by potato peelings.

ZT-M: I was so surprised by that work. In a way, it sort of made itself, and I managed to get out of my head as it revealed itself. My hand was in it, and the hands of many others were in it. I did spend a whole day putting each of those potato peels in position in the gallery, but overall the way it unfolded was surprising and fun for me.

ST: There are so many ways that project could’ve ended up looking. I always think, with materials, there are two ways: you can make the material do what you want it to do, or let the material teach you.

ZT-M: Yeah, and even those blimmen potato sacks. I unmade and remade it the week before it went into the gallery because it was like, Zoe, you’re trying to make this material do something it doesn’t want to do. Sometimes I don’t trust my ability to go with the flow, so I want to control things. The potatoes turned out more wonderful than I could have imagined, because I just let them be. So that was a significant learning moment for me with my practice.

I also wonder, where’s the space for failure? We don’t really talk about all the failures

ST: I don’t have children, but I imagine my art practice is something like when a child pushes back and says, “I’m not that.” And my job is to accept that. I’ve learned over the years that pushing doesn't end up anywhere good.

ZT-M: We don’t make the work, the work makes us, and that’s really exciting to me. It’s an embodied way of being in the world. Sometimes you just have to put your hands into the soil, and although you can’t see anything, you can feel that something is there.

I also wonder, where’s the space for failure? We don’t really talk about all the failures, you just see the work in the gallery and it gets taken at face value. I think that’s why I take solace and grounding in just attending to something every day.

Do you feel like that sometimes? You finish something, but you don’t know what’s next. I can often feel the energy is starting to shift, but I still don’t know what the next thing is about.

ST: Until it rises! I remember reading a cook writing about making bread, and he said, “Don’t knead it continuously, take a break. It’s not just for you; it’s for the bread as well. Just let it have a little rest.” I love that description, it’s not just do, do, do!

ZT-M: Totally. I’m really interested in that. Sometimes the best thing to do when you don’t know yet is do nothing because it’s not nothing, it’s potential. How do you harness that potential? You’ve got to have that moment where you just wait.