Why Can't We All Just Get Along? The Literature Edition

Tusiata Avia, Vaughan Rapatahana, and Maria McMillan talk to Literature Editor Sarah Jane Barnett about how, in a world full of unexpected, unknown and unconscious bia, we can all just get along.

In a world full of unexpected, unknown and unconscious bias – our own and other people’s – sometimes it feels easiest to stand in our own monocultural or monogender corners, feeling lonely, looking at our toes, too scared to talk to or about each other. But. Ew. How do we have fun together without inadvertently fucking each other off? In this 4-part series looking at visual arts, literature, theatre and public commentary, we ask some experts for their ideas about how we can all get along.

Edition 2: The following is a conversation between poet and performer Tusiata Avia (Samoan, Palagi), poet and academic Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Atiawa, Ngati Te Whiti), poet Maria McMillan (Pākehā), and poet and Books Editor Sarah Jane Barnett (Pākehā). They agreed to approach the conversation as a talanoa, a Pasifika way of relating personal stories in order to learn about an issue, rather than forming an argument or adversarial problem solving; the process is its own outcome.

Sarah Jane Barnett: I need to start by saying I’m nervous. I’ve been an editor at The Pantograph Punch for a year, and in terms of what this conversation is about – structures of power, who has the right to speak – it’s been a fucking humbling experience. Before being an editor I didn’t realise how much my Pākehā identity informed my behaviours.

What really brought it home was when researcher Belinda Borell (Ngati Ranginui, Ngai Te Rangi, Whakatōhea) came to talk to the Pantograph editors at our strategic retreat. She showed us the research Alternatives to anti-Māori themes in news media, the first theme being ‘Pākehā as the norm.’ While I’ve always identified as Pākehā, the conversation hit home in a way it hadn’t before. I've become more active in understanding the experience of non-Pākehā writers.

Framing our conversation is Janis Freegard's work on inequality in publishing in Aotearoa. To summarise, her 2015 report revealed that while there is the appearance of gender equality, there is no such equality in terms of the ethnicity of published writers. As Freegard states: 'Of 68 titles, Pākehā writers got 91% of the pie; Māori writers and Asian/Indian writers got 4%…and Pasifika writers got 1%.'

Pākehā writers are 4 ½ times more likely to be published than a Māori writer, 3 ½ times more likely than an Asian writer, and 8 ½ more likely than a Pasifika writer.

To put those percentages into context, the 2013 New Zealand census showed that 74% of New Zealanders identify as Pākehā, 15% identify as Māori, 12% as Asian, and 7% as Pasifika. If we compare those percentages to Freegard’s stats, it means that Pākehā writers are 4 ½ times more likely to be published than a Māori writer, 3 ½ times more likely than an Asian writer, and 8 ½ more likely than a Pasifika writer.

What are your experiences of power imbalances in Aotearoa literature, or ways in which you've been prevented from having a voice?

Tusiata Avia: Thanks Sarah Jane for being willing to go with a talanoa type kaupapa – it takes the pressure off and let's me say whatever comes to me without having to construct an argument. For me this is talanoa in the va – an open conversation without needing an outcome in a relational space.

One of the first things that came up for me reading the Freegard stats is the voice in my head that said: ‘See, Tusiata, they didn't just publish you because you are Pacific’ – because of course – compared to Pākehā we are underpublished. I can't tell you how many times it's been suggested to me that I've been published because I'm Pacific. Not because what I've written is good or has merit, but solely because I'm ticking some Pacific funding/ equity box, and therefore a real deserving (i.e. Pākehā) writer is being penalised.

This, by the way, isn't just limited to when I've been published – it's the same story for when I've received residences, fellowships, awards, grants, invitations to festivals, jobs and the way I've been programmed in festivals. Early in my career, when my show Wild Dogs Under My Skirt was produced for the first time in a professional theatre, I was told by an industry 'professional' – in that just-so-you-know kind of way – that I was no doubt being included in that theatre's programme because I was brown.

Why do we have to be reviewed together? Because, of course, we are brown.

That was also the week that Unity Books in Wellington racially profiled me for the second time, accused me of shoplifting and publically humiliated me, just weeks before the book version of Wild Dogs Under My Skirt hit their shelves. I've never been able to step foot inside Unity since – the thought still makes me sick to my stomach.

Sarah: What an incredibly difficult experience. Racial profiling is the horrible flipside to accusations of favouritism.

Tusiata: We – I can probably speak for a number of us because I've had this conversation with a number of published Pasifika writers – are always dealing with this silent, or not so silent, accusation of special (i.e. undeserved) treatment. That anyone believes the odds are stacked in our favour needs to stop right here. Let's all just stop and read Freegard’s stats again: Pākehā writers are EIGHT times more likely to be published than a Pacific writer. EIGHT.

Back to this ‘special treatment’ bullshit. It leaks quickly and poisonously into your consciousness and then you're second guessing everything: ‘Am I only getting that book contract/writer in residence/award/grant/fellowship etc. because I'm Pacific?' It's insane. It's racism worming its way into your insides and eating its way back out and leaving a trail of shit in its wake. When you are only viewed as a colour – when that is the only lens the literary world will see you through – it is hard not to then see yourself that way too.

The most recent review of my most recent book Fale Aitu/ Spirit Housewas titled 'Young, Gifted and Brown.' The review was nice enough, but I was reviewed with two other Pacific writers (Courtney Sina Meredith and Simone Kaho) who are both superb writers, BUT, why do we have to be reviewed together? Because, of course, we are brown. This incenses me. Stop drawing a line around us. Stop othering us. Stop making us into an exotic, niche sideline. Stop ghettoising us. We can cut it with the big girls and boys in the mainstream, thank you very much! Yes, we are Pacific, and proud of it, but we are writers. Let us be writers.

Vaughan Rapatahana: Kia ora mo tenei kowhiringa. So, where to start, eh?

I am not monocultural nor monolingual and nor is my whānau. We are multiethnic. The English language is not our prime medium. I have lived overseas for a large proportion of my life – in Republic of Nauru, Brunei Darussalam, PR China, Hong Kong, Brunei Darussalam, UAE among others. We continue to go back and forth – rather like a talanoa moves incessantly between conversation, story, conversation actually (see Jione Havea in Black Marks on the White Page) – between Aotearoa, Philippines, Hong Kong SAR. My point? I reckon I have a pretty good insight as what being marginalized is like. And certainly also in this skinny country when growing up in Mangere and living in Matakaoa.

None of this is a surprise: Māori, Pasifika, Asian writers are proportionately under-represented... Write in our own languages and be damned.

Marginalization occurs when the dominant culture rules regnant over other cultures and maintains this power base via hegemony; cultural capital, colonization often via bloodshed (I could quote several fine books here, including The Blood Never Dried by John Newsinger) and so on and so forth. The dominant culture is of course Anglo-American, vested in the English language and enforced and encapsulated by male plenipotentiaries and female surrogates. They will not give up their power willingly.

As throughout Aotearoa New Zealand and specifically in the field of literature as Janis Freegard has shown and as Paula Morris has also pointed out fiercely in a recent article. None of this is a surprise: Māori, Pasifika, Asian writers are proportionately under-represented and will continue to be so long as the regime remains. All the more reason therefore to write against its strictures, tenants, mores, monopoly games.

Sarah: Yes! How do you see writers doing that?

Vaughan: The element of Pākehā guilt permeating New Zealand life does enable some avenues for non-monad authors to keep on writing. So seize such opportunities, I say. Take hold of them to resonate further your non-mainstream voice. Write in our own languages and be damned, I say. Tusiata – there are some damnably fine writers such as yourself who I think would be published anywhere, given the scenarios and stereotyping you have witnessed. There is an ongoing battle here. This is not a playground scrap. Ka whawhai tonu mātou – struggle without end.

Maria McMillan: I come from a mostly monolingual English-speaking Pākehā family, both literate and literary, my father is a journalist and the house I grew up in was filled with books. Writing and reading were enormously valued.

I don't think we can separate out what is happening in New Zealand literature from the power dynamics in wider New Zealand society, the racism, the sexism, and the legacy of colonialism and its on-going enforcement. My own background undoubtedly eased my path to both writing and eventually being published, and I’ve received some rock solid support. It feels to me that around Wellington (which is the writing community I know best), there’s a huge upsurge of women engaged in writing, publishing and criticism; it’s intergenerational, supportive and tremendously exciting.

I don't think we can separate out what is happening in New Zealand literature from the power dynamics in wider New Zealand society, the racism, the sexism, and the legacy of colonialism.

Despite that, I’m acutely aware of undercurrents and attitudes that feel hostile. When I see middle-aged New Zealand male poets write demeaningly of their wives, or of their cocksure fantasies about young women, it's boring and familiar and it’s getting published. And as Vaughan's recent essay pointed out, the entrenched sexism has been going on for one hell of a long time. I think women’s and men’s writing is probably received differently as well. I think particularly of some of the negative reviews of Pip Adam’s books. From a male writer I wonder if the originality and intelligence would be more readily accepted.

Sarah: An excellent point – I think you're right.

Maria: Then there’s the familiar double whammy of gender and ethnic marginalisation playing out again and again in reviews like the one Tusiata mentions. Or more recently where our Poet Laureate (in her mid-40s) was referred to as 'feisty,' a 'gutsy young woman' and a 'warrior poet.' Albeit well intentioned, I do not believe those phrases would be used about a 40-something Pākehā male poet.

I don’t think of New Zealand literature as pale, male and stale at all. Despite structural and systematic challenges, despite hostilities, despite under-representation, we have a literature whose guts, and mind and life force is held by women, by indigenous, and by minorities. When I think of who is pushing, and expanding and extending what the literature is, I think of Tusiata, Hinemoana Baker, Gregory Kan, Chris Tse, Tina Makereti, Hera Lindsay Bird, and Witi Ihimaera. I think of the blossoming of small presses Anahera Press and Seraph Press, specifically started to publish a greater range of voices. I think of the South Auckland spoken word scene. They are at the heart of the entire realm; publishing, financial resources, and the attitudes of some reviewers need to catch up.

I don’t think of New Zealand literature as pale, male and stale at all.

I’m not for a moment denying the limited access some groups have to engage in New Zealand literature. I think about who has access to literacy itself, and the ability to read and write at even the most basic levels. Māori and Pasifika are over represented in poor literacy rates, as are kids from lower socio-economic backgrounds. For a long time, it was known that the particular methods employed in New Zealand literacy teaching were failing, and were particularly failing Māori and Pasifika; those methods were continued anyway. The kids weren’t flawed, their needs weren’t different, the method of teaching was flawed. We are never going to have a literature that truly represents the brilliance of our diverse if kids aren’t given the building blocks to tell their stories.

Sarah: When reading your messages I hear anger and frustration, but also determination. As you say Vaughan, it’s an ongoing struggle, and as Maria points out, many of the writers who push us forward are from under-represented groups. While Aotearoa’s small population is challenging in terms of funding and a robust review culture, it does allow writers and presses to take risks and change the literary landscape in ways that might not happen in a larger country.

As a Pākehā editor, I think about how to create a space that is inclusive and equitable. Tusiata, I think your experiences of being ghettoised and othered are Pākehā editors, reviewers, and festival organisers trying (and failing) to create that space. I am not defending their choices – simply putting a marker in the sand to say, this is where we are. I often see Pākehā, myself included, get tangled up in trying to ‘do the right thing,’ but through that process they erect a wall between themselves and the other person. Pākehā guilt, for sure, but also I suspect Pākehā fear of failing. Pākehā culture values clear, precise answers, but people don't connected in this way. How can we be messy together? What collaborations have worked for you?

Tusiata: How can we be messy together? It is all intrinsically messy – this whole relationship between PoC (people of colour), the literary community and the wider community in Aotearoa. And it’s painful. Sarah Jane, you mention Pākehā guilt and (my) anger and frustration: it’s all that and a whole lot of sticky, spiky, stinging threads running through this space.

I listened to Reni Eddo-Lodge, author of Why I’m No Longer Speaking To White People About Race, speak about white privilege and structural racism at a Christchurch WORD Writers Festival event recently. She spoke in a way that articulated things I have only been able to say in poetry. I’ll probably quote her at some point.

What is hopeful for me, Sarah Jane, is that you’ve started this talanoa (open-ended conversation) acknowledging your own Pākehā privilege as the editor here. It’s an important dynamic in this va (relational space). It’s a dynamic not often acknowledged, in fact, this is a first in my experience. In my experience, white privilege is almost always invisible to white people. A quote from Reni: “To be white is to be human; to be white is universal. I only know this because I am not.” Herein lies the mess.

For me, collaborating is not an issue – I am doing this all the time... I’ve had commando training in learning to survive, and even succeed, in white institutions.

For me, collaborating is not an issue – I am doing this all the time. As a PoC working with a Pākehā literary community (we know that the publishing world is overwhelmingly Pākehā), I am doing this with every single transaction. I’ve gotten good at it. But then I’ve been training for it since I started school in Christchurch in 1971 at age five. I’ve had commando training in learning to survive, and even succeed, in white institutions. One of my lifelong, constantly repeating lessons is, to quote Reni again, that “It’s truly a lifetime of self-censorship that people of colour have to live. The options are: speak your truth and face the reprisals, or bite your tongue and get ahead in life.”

Sarah: What I’m hearing is that collaboration has always been on someone else’s terms.

Tusiata: Biting your tongue is a way of life, a way to get by, a way to succeed, an automatic safety default mechanism, but it’s also always accompanied by the sick feeling in the gut, the stone lodged in the aching-robbed-of-speech throat – the instinctive response of the body to the white privilege that you are subject to in the most subtle and the most outrageous of manifestations.

Luckily for me and my sanity, for the last seventeen years my poetry has been my voice, the place I can un-bite my tongue, where I can express the things I’ve wanted and needed to, the things that I don’t dare to in my daily dealings with a world of white privilege. This space here is not one I am used to expressing this kind of stuff so freely in – to be honest it feels pretty risky – my fear in this moment is that I come across as Angry Brown Woman railing against the poor old literary community and all white people. But some of my best friends are white.

To answer your second question: what collaborations in the literary community have worked for me? Collaborations with other PoC come to mind immediately, but if the literary community is white, by definition, then I really have to think about it. What has worked for me where I didn’t have to bite my tongue or be on my guard?

Here’s one: working with Coca Gallery in Christchurch as Writer in Residence; the Pākehā curator took ownership of their own cultural gap in consciousness and didn’t expect me and the other PoC to do the work for them. On top of that, they were willing to advocate for the PoC and other diverse artists with the (white) hierarchy. That was a huge relief – to be taken care of like that! And to not be expected to be spokesperson for all brown women. To witness that curator do their own personal/cultural work, and take responsibility for their own shit, was a revelation for me. It was a beautiful and vulnerable thing, it bridged the va, it built respect and mana and forged a friendship between us.

Sarah: The curator sounds very self-aware!

Tusiata: That’s what it takes: recognising your own privilege and then being willing to be open and vulnerable with it. It’s uncomfortable and we’re human, and when shit gets hard and embarrassing and shameful, we want to move on from that uncomfortable moment and maybe look instead at the bright side. But that’s a deflection.

You – and here I’m talking to Pākehā – have got to be willing to at least consider your privilege. Recognise it. Educate yourself.

You – and here I’m talking to Pākehā – have got to be willing to at least consider your privilege. Recognise it. Educate yourself. Read Reni’s book. Or something else. Do the emotional work around it. Feel the discomfort. Then, we can start truly being in this mess together.

Maria: That's really interesting what you say Tusiata, and though you have every reason to be, you don't sound angry; you sound tired and tolerant.

Guilt has been brought up a few times, and I think it is probably rife among the Pākehā literary community, who – as I think Sarah was saying – do want to do the right thing. I had a fair crack at feeling guilty for a long time, so I know all about it. I think a lot of well-meaning Pākehā are totally up for doubling over in pain for decades at a time over how crap our ancestors and contemporaries are behaving around the whole stealing someone else's land, language and self-determination thing. And then white privilege – in Pākehā online communities there's this crazy calling out each other on privilege stuff. It's descended from being a useful acknowledgment of how society works, to a point scoring and self flagellation.

I also think, as a Pākehā who cares about justice, you come to realise the extent of injustice imposed through colonisation and it's easy to feel a real sense of not belonging. I think a lot of people go through the feeling of holy crap, this is stolen land, and I don't really belong here. And I don't really belong anywhere else, and I have a culture premised on being crap to other cultures. And what does make me?

Sarah: These are definitely feelings I’ve had to work through.

Maria: Those feelings can get twisted in to bad or embarrassing behaviour, like worry and doubt which leads to people making up rubbish about Māori and Pasifika getting advantages or having it easy. It also leads to the co-option of culture, because sometimes it’s easier to pretend you are Māori or Indian when you don't like the implications of being Pākehā. You believe you are spiritual and nice and decent so really deep down you must be Māori. Or seeking endless approval from Māori (who might be, you know, busy), and deciding every single thing anyone Māori says should be revered no matter how ridiculous.

Guilt, I think, is understandable and un-useful. The reason that I bring all this up is that in order to actively engage in the struggle, to be in, really in the mess alongside Tusiata and others, who don't have any choice about it, we have to feel comfortable in our skin. We have to know who we are and what we're made of.

For me, to really start being okay, it was about figuring out my own blood ancestry and the stories of my family being in Aotearoa... the idea that I had honourable ancestors and could myself be honourable.

I saw someone on Twitter responding to what must have been your talk at the Queensland Writers Festival, Tusiata, when you said we need to know what combination of molecules we're made up of. The tweeter heard you and it moved him and made him think about understanding their queer whakapapa. You gave them a moment of understanding.

I had my own turnaround moment in a decolonisation workshop run by the wonderful Freedom Roadworks group. Marie Laufiso, one of the facilitators said, “Find your honourable ancestors.” For me, to really start being okay, it was about figuring out my own blood ancestry and the stories of my family being in Aotearoa. Let me say, we need to unblinkedly acknowledge the history of colonisation and racism perpetuated by Pakeha, but after years of guilt ridden confusion and not understanding what role Pākehā had, the idea that I had honourable ancestors and could myself be honourable was big.

The reason I bother talking about this is that as Pākehā, with the privileges that bestows, we can make more meaningful contributions to the struggle for justice, whether in or out of the literary community, if we have a good sense of who we are, of knowing our own ground, of not being entirely tied up in knots with guilt. We're more likely to support movement of thought among other Pākehā when we get to the point of believing that we're all equally capable of decency and goodness and brilliance. We need to hold our own integrity.

Vaughan: Yunno, I wanted to write more about why people of colour (PoC, although Indigenous is a far better term) are in the sheer minority of being published or being publishers, eh. Yes, white privilege and potency, which impels PoC to exist on a lower socio-economic plateau, whereby books, publishing, even bloody reading, let alone writing anything, is a no-no because there is no money to buy books, let alone find the time to write/read them – too bloody exhausted anyway, eh.

As for becoming an editor, how does this work if you drop out of school to support your whānau by working in the local abattoir when Dad is in prison?

As for becoming an editor, how does this work if you drop out of school to support your whānau by working in the local abattoir when Dad is in prison? And part of this abiding process is – as Maria cogently mentioned – PoC all too often have issues with regard to at least English language proficiency anyway. All interrelated with this general cultural misalliance is the point that the monad publishers tend to publish some Indigenous themed work solely to earn $$$. I can include along this continuum work by women, transgender, gay folk – although of course this is slightly less so now.

Sarah: You say Indigenous is a better term than PoC. Could you expand?

Vaughan: People of colour is the loser in the binary opposite of that term and a term designating people of no colour (white). See Derrida for his notion of binary opposites, whereby there is always a more powerful component. PoC is not the powerful binary opposite. Indigenous (with a capital I, generally) describes the first settlers of a space; they are 'native' to a land and do not have some commonality of colour. Think Welsh and Scots, both of whom were severely oppressed by the same Anglo forces and lost land, language, culture accordingly. Manifestly they are not PoC. Indigenous in relation to Aotearoa NZ is Māori – especially as grounded in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

What then of Polynesian qua Pasifika and Asian writers? If they have lived in New Zealand generationally for some time and/or are born here, they are indigenous (small i). Yes, they are indeed not represented sufficiently regarding their published work, but this will change as statistically they overhaul the Pakeha majority. More these latter indigenous groups, as well as Spanish-speaking, French-speaking et al minorities, are producing their own works in their own tongues regardless; there are Filipino newspapers here, as written in Tagalog and English.

We have our own tradition of mōteatea or song-poetry and we perform this in another parallel realm within Aotearoa.

To continue, most/many Indigenous are not interested/are light years away from the topos (traditional themes) of Pākehā majorities anyway. Nor – importantly – do we write in English language formats, when we write at all, eh. Our Māori and Polynesian tradition is oral. We have an ontological difference as to our ao, our tikanga, our kaupapa or subject matter and the concomitant method/manner of delivery. This is a key point in this our talanoa. We are existentially DIFFERENT.

Which leads onto this prime point too: we have our own tradition of mōteatea or song-poetry and we perform this in another parallel realm within Aotearoa. This tradition includes waiata, ruri, oriori, and haka te mea te mea te mea. Indigenous are doing it for themselves – at least to a degree in this country. Screw the mainstream publishing ethos.

Sarah: Mainstream publishing is just one avenue.

Vaughan: I would like to say the poetry slam at the Going West Festival on Saturday night was most enjoyable, not only of course, because of the talent and the delivery, but because of the wide cross-section of Kiwis working together. The judges were Renee Liang, Karlo Mila and myself. The organisers were Doug Poole and Penny Howard. MC, Zac Scarborough. Deliciously multi-ethnic. And the competitors were all brilliant – Māori, Pākehā, Samoan, and all three genders too. No condescension, No ego trips. It shows that indeed we can all get along at a literary event and in a wider nexus.

And, you know what, eh, Aotearoa New Zealand will become, is becoming more and more multicultural, much to the apparent disgust of Winston Peters et al. There will continue to be a major demographic shift towards Indigenous and PoC and mestizo or mixed race.

There are already (literary) collaborations, for example last years' Twelve Heavens poetry compilation and performances instigated by this country's increasing Spanish-speaking population, including Spanish translations of Māori poetry. There are also more small presses publishing almost primarily Māori authors such as Kiri Piahana-Wong's Anahera Press, and Anton Blank's fine Ora Nui series. And, of course, Huia. I should have mentioned them in the talanoa. This country is changing.

Sarah: We're at the end of this talanoa. Drawing on what Maria said about 'honourable ancestors,' I thought we could end by sharing our 'literary ancestors.' Not necessarily who inspires you (although that too), but a writer whose voice gave you permission to write in your own voice. For me it's Anne Kennedy for her inventive and unashamed poetry about domestic spaces, motherhood, and the experience of women. I will never stop loving her work.

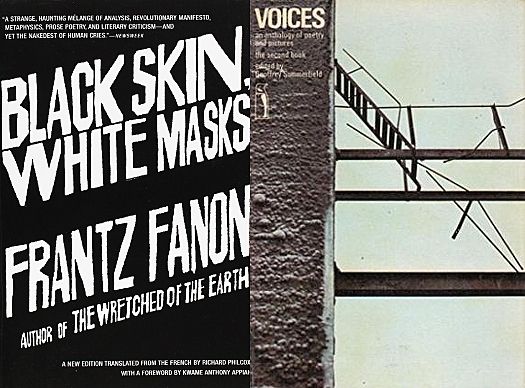

Vaughan: Te Whiti o Rongomai – goes without saying for me: "Just as night is the bringer of day, so too is death and struggle the bringer of life"; Frantz Fanon – key harbinger depicting need for decolonialization in works such as Black Skins, White Masks, and The Wretched of the Earth; Hinewirangi and JC Sturm for their honesty and courage writing against the regime in Aotearoa; Sylvia Plath for her confessional work which is brutal yet vital. There are several others, but these are bedrock for me.

Maria: Voices was this amazing UK series of anthologies edited by Geoffrey Sommerfield that came out in the late 60s early 70s. They were floating around our house when I was a kid and were very eclectic and global; not just Europe, African, and the Americas, but Asia and New Zealand. They were diverse gender-wise and ethnicity-wise. They felt political and alive, and I learnt about writing as being part of a long tradition, and about writing being something people did to be part of the world.

I learnt about writing as being part of a long tradition, and about writing being something people did to be part of the world.

I mentioned earlier growing up in a house full of not just books but New Zealand books. A wonderful seventh form (Year 13) English teacher, Helen Leahy got us studying The Bone People, Owls do Cry and Katherine Mansfield. The Bone People was only a few years old so the idea that contemporary Aotearoa literature was part of a long tradition was reinforced. I was going to mention Plath and Fleur Adcock. Later I got absorbed into Adrienne Rich's poetry which I have mixed feelings about now. But she was a phenomenon to me, to be writing these lengthy conversational yet absolutely poetic pieces about important stuff. She changed language.

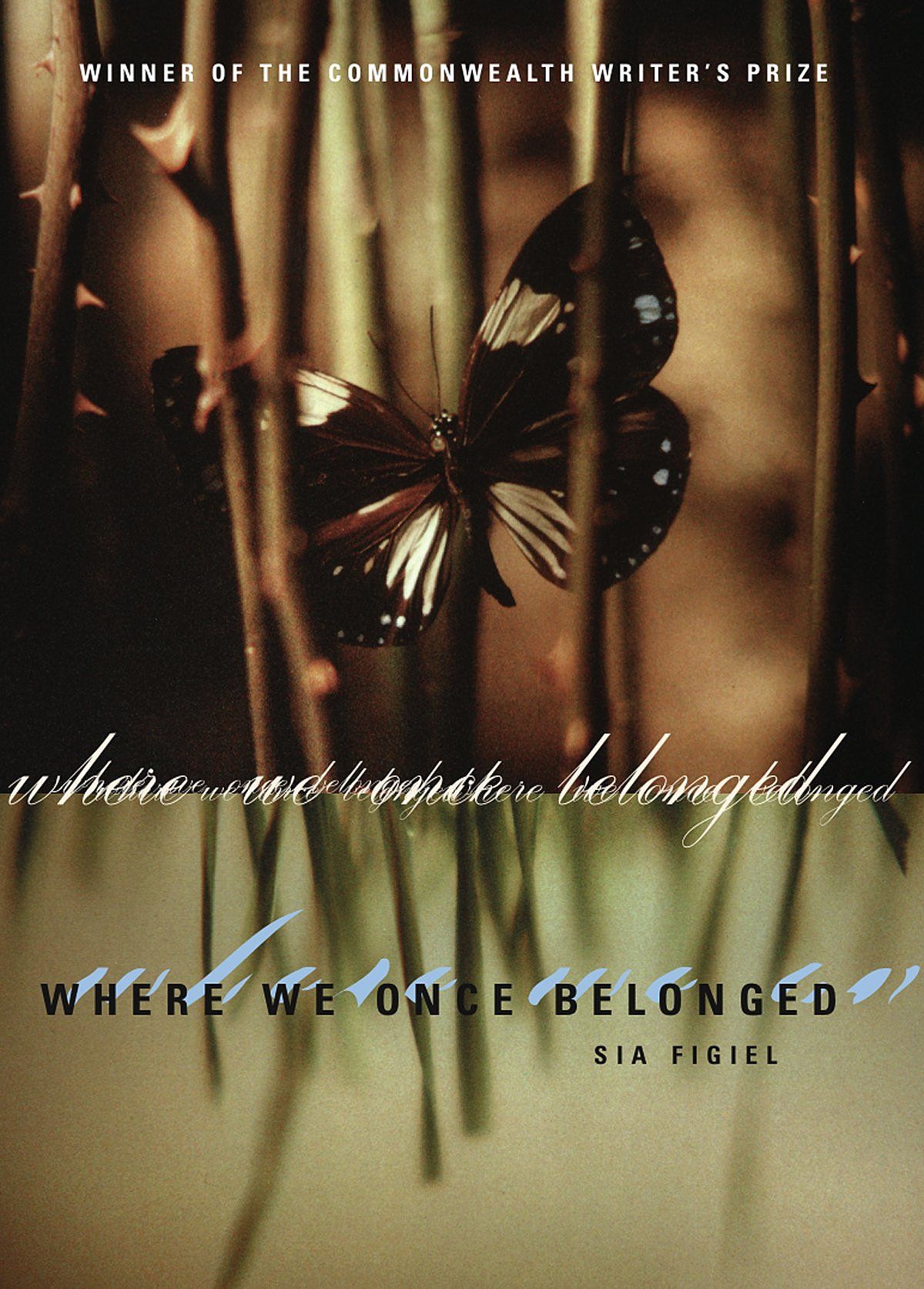

Tusiata: Like for so many Pacific people, Albert Wendt was the wayfarer for me – he was the one to write us into the white space. I was so obsessed by his first novel, Sons for the Return Home, that when I found it in the library in my first year at uni I smuggled it out because the library was closed and I had to finish it that night. But it was Sia Figiel’s Where We Once Belonged that opened the door for me. I remember sitting up with a start and saying out loud in my cold London flat, “This is possible?” It wasn’t long before I had made the return home to New Zealand to do what I had thought was impossible – to write myself into that space.

I love it when a writer or a piece of writing opens that door for me or allows me to open that door for myself. Sharon Olds has done that for me – her work is unflinching, searingly and beautifully honest to the bone. Selima Hill’s poetry. Sapphire’s novel, Push. Anne Lamott’s books on writing. The adventures of the Samoan goddesses will inspire me forever. Although, mostly I have to research their stories in libraries, my connection to their stories is profound – their voices will keep ringing in my work till I go to join them.