Complex and Disturbing: A Review of Ruth Watson’s 'Geophagy'

Ecology, second-hand clothes and the 'Anthropocene', Virginia Were chats with Ruth Watson before contemplating her latest exhibition at Gus Fisher Gallery.

Ecology, second-hand clothes and the 'Anthropocene', Virginia Were chats with Ruth Watson before contemplating her latest exhibition at Gus Fisher Gallery.

Entering the foyer of the Gus Fisher Gallery to see Ruth Watson’s Geophagy, you’re confronted with an enormous bulky stack made from recycled wooden pallets, which towers above you and kisses the stained-glass dome in the gallery’s ceiling. This wondrous Tower of Babel-like sculpture is one of four distinct works in the exhibition, and announces Watson’s first major solo show since 2012. Geophagy is the name for the curious practice of eating earth and Watson uses it as a metaphor for humans devouring the planet earth. Continuing with her longstanding interest in maps and mapping, she grapples with one of the most urgent issues of our time – our relationship to the environment – through a juxtaposition of environmental, social and cultural theory and personal memoir, which helps lighten the intense, at times intellectual mood of the show.

Tucked into and draped over this monumental stack are hundreds of items of second-hand clothing – a multi-coloured skin that sags, folds and festoons the stacked wooden pallets that form the armature of the structure. These grey cardigans, threadbare shirts and faded hoodies were purchased by the kilo and have all seen better days. No designer labels here.

This shabby clothing reminds me of post disaster photographs in which fragments of clothing are poignant reminders of individuals who lost their lives. These kinds of images contain a horror that more general disaster photographs lack. I’m also reminded of what aid workers describe as “the second disaster” which occurs when concerned and undoubtedly generous citizens donate vast quantities of clothing, blankets and other items. Sadly, these gifts are often of no use to those in need, causing logistical nightmares for aid workers and relief agencies who must somehow dispose of them.

All those plastic microfibers go out into the ocean when you wash them, and so fish are eating them and they are killing life on earth – but we don’t really think about this when we buy, let alone wash, our clothes.

It would be easy to make a connection between Geophagy and Christian Boltanski’s unforgettable Personnes for Monumenta 2010, at the Grand Palais in Paris. Boltanski filled the cavernous space with enormous piles of old clothing, some of which were continuously picked up and dropped by a crane to the accompanying sound of amplified heartbeats. Although Watson admires this Holocaust inflected work, she prefers to reference Venus of the Rags, 1967, a garden-scale version of the Venus de Milo facing a pile of brightly coloured clothing by the master of Arte Povera, Michelangelo Pistoletto. Watson’s use of clothing is particular. During our interview, she comments, “My Facebook feed regularly coughs up terrible news about environmental disasters, and the clothing industry is a huge contributor to this. We’re of an age where we can remember our mothers making most of our clothes and you would buy something as a treat. Now it’s the reverse – we buy everything and throw things away at the drop of a hat. The work is about a particular form of consumption – most of those clothes have got plastic in them. The stack is 200 kilos of clothing ordered from a company that sells second-hand clothes by the kilo. All those plastic microfibers go out into the ocean when you wash them, and so fish are eating them and they are killing life on earth – but we don’t really think about this when we buy, let alone wash, our clothes.”

Emanating from the monumental stack is an indistinguishable babble of voices, each one competing for your attention. Immediately you’re confronted by a feeling of excess. Too much stuff, too many opinions, too much information. Watson’s work is a fantastic evocation of consumerism gone mad and the way the world feels today. Overwhelming.

The voices come from five small monitors embedded at different heights in the stack (think Nam June Paik’s 1960s installations with televisions placed in unexpected places). One of them shows the disconcerting close-up of a masticating mouth. Yet another clue that Watson is thinking about consumption.

Stand close to the monitors and you’ll hear chapters from five writers and philosophers on Watson’s current reading list, including Susan Schuppli, whose article ‘Slick Images: The Photogenic Politics of Oil’ discusses how catastrophic industrial disasters, like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, have spawned a cascade of photographic images which have become complicit in the environmental wrongs they depict. Schuppli writes that scientists are debating whether we’ve entered a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene – which is another way to describe humanity’s profound impact upon the earth. “Anthropogenic matter is relentlessly visual in throwing disturbing images back at us from which we should recoil, were we not part of this same obscene metabolic order.”

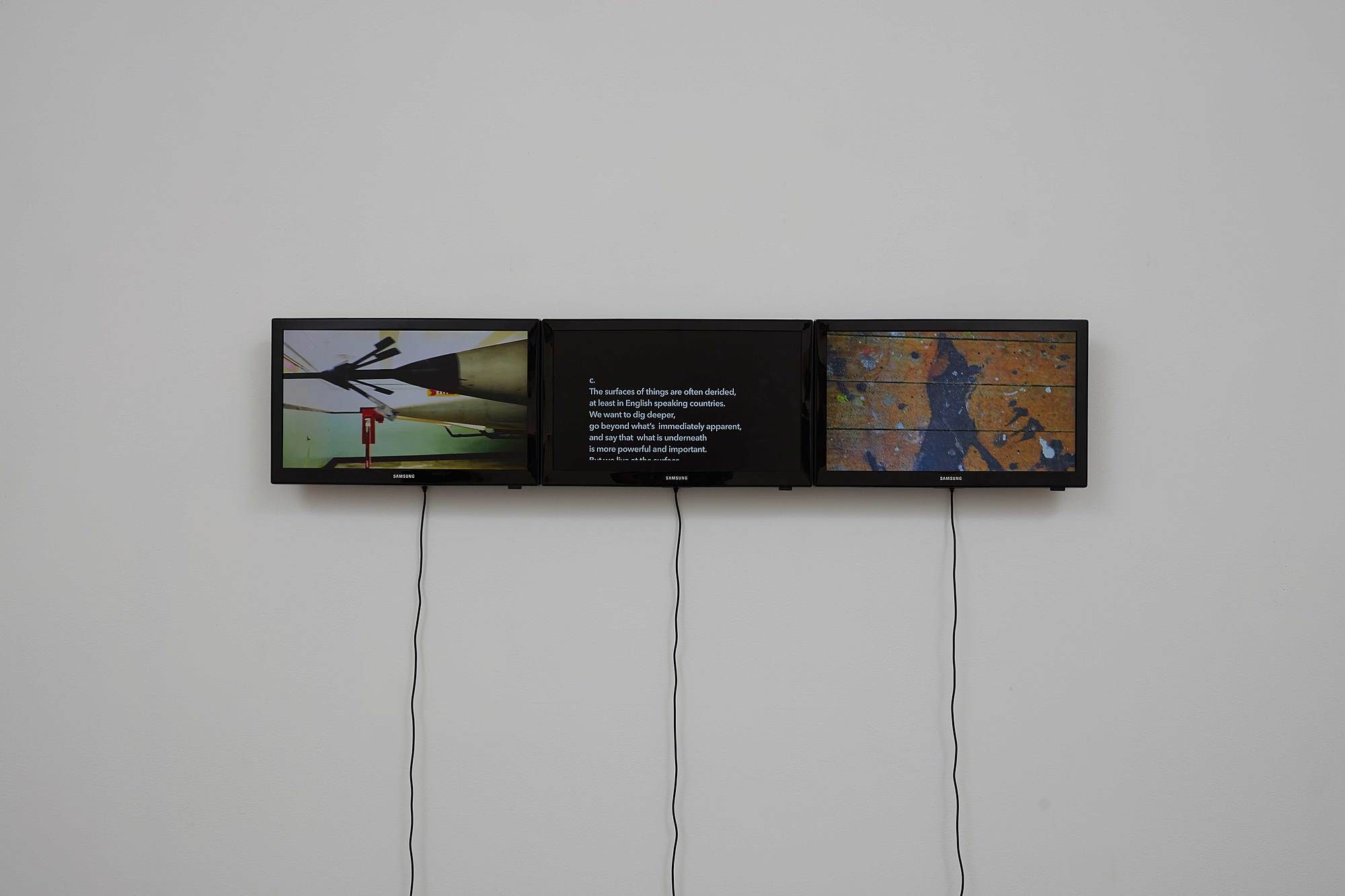

Of the four works in the exhibition, three were made specifically for the show but the fourth, The Surface of Things, was made while Watson was artist in residence at Headlands Centre for the Arts after winning the 2015 Fullbright-Wallace Arts Trust Award. This three-channel video meditates on the idea of the ‘surface’ – both physical and conceptual. In one of the three videos we see close-up footage of the floor of the Headlands studio with all its spots and speckles of paint accrued over its long history as a former military barracks and then as artists’ studios. In another we see footage Watson shot while visiting the decommissioned Nike missile site nearby. On the third screen Watson’s poetic text is a personal memoir which glides effortlessly over a wide conceptual terrain, considering the almost compulsive desire of artists to go ‘deeply’ into things while ignoring the obvious. She emphasises the importance of the surface, likening it to the earth’s crust, and the skin of our bodies.

On the opposite wall are nine framed photographs of maps Watson found discarded on the streets of Auckland, and collectively they’re titled, Transient Global Amnesia. These maps are in varying states of decay – a clever visual analogue for the sudden onset of memory loss caused by the medical condition described by the title. And perhaps also for the condition we humans are suffering from at present. The white flecks of the disintegrating maps find a pleasing echo in the fragmented pattern of the Gus Fisher’s terrazzo floor.

Watson’s narrative considers whether her own choice not to procreate was an ethical one, and concludes that it wasn’t.

The fourth work is Unmapping the World, 2017, a single-channel looped video whose dreamlike images include aerial footage of Antarctica, an educational video about maps, and personal items that look like family heirlooms – a green handkerchief, which may have belonged to Watson’s Irish great, great grandmother Sarah who emigrated to New Zealand. The spoken narrative shifts seamlessly between past and present, personal and political and we hear the tragic story of Sarah, who died in the family home while giving birth to her ninth child. We’re told that reading the coroner’s inquest into Sarah’s death was harrowing for the artist. Watson’s narrative considers whether her own choice not to procreate was an ethical one, and concludes that it wasn’t. Instead it may have come from a fear of having children, which dates back to this traumatic family event. Even though it occurred three generations ago, it continues to reverberate in the present.

Echoing Donna J Harraway’s discussion of pro-natalism in her book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, which is one of the voices you hear in the stack, Unmapping the World touches on overpopulation and the West’s condemnation of China’s one child policy. During our interview Watson comments, “It’s hard to take a position against, or even discuss, what some people in the world call “pro-natalism” and not be shot down as a fascist, communist or eugenicist – it’s a conversation we’re not allowed to have.”

In the video, Watson doesn’t elaborate on why someone’s choice not to have children may be considered an ethical one in the context of environmentalism. Rather, she assumes that the connection between overpopulation and ecological crisis is self-evident. Too many people, too much waste, too few resources. This is referred to beautifully in the Jorge Luis Borges quote at the beginning of the video: “Mirrors and copulation are abominable, since they both multiply the numbers of men…”

There’s a whirling and looping of time in Unmapping the World which underscores one of Geophagy’s key propositions – that although in the affluent West we’re taught to believe in our own agency, our ability to shape our destiny, isolated from the circumstances of the past, in fact we’re dominated by unseen forces – both past and present – that swirl around us in the age of late capitalism. Great, great grandmother Sarah’s awful fate and the way it has affected Watson’s life is offered as evidence of that.

Although Geophagy is undoubtedly a lament for the deplorable state of our planet in the Anthropocene, it’s much more nuanced and multilayered than many so-called environmental artworks. Watson has no answers.

Not surprisingly, over the last decade environmental art has become de rigueur as the ecological, social and political effects of climate change begin to bite deep across the globe. On our own doorstep savage and unpredictable weather wreaks havoc on our lives. Although Geophagy is undoubtedly a lament for the deplorable state of our planet in the Anthropocene, it’s much more nuanced and multilayered than many so-called environmental artworks. Watson has no answers. Rather than presenting us with gloomy statistics and images, or compelling us to take action before it’s too late, Geophagy combines different media – sculpture, video, photography and text – and different modes of expression – fiction, contemporary philosophy and autobiography – to echo the complexity of the situation and the seeming impossibility of understanding, let alone solving, this calamity. Despite the overwhelming evidence of impending environmental catastrophe and the urgent need to ‘do’ something, it’s far from clear ‘what’ individual or collective action we should take. In a word – overwhelming.

Geophagy

Gus Fisher Gallery

28 April 2017 – 27 May 2017-06-01

Exhibition Photographer: Sam Hartnett

All photographs courtesy of the artist and Gus Fisher Gallery