A Gentle Communion: Considering 'Sleeping Arrangements'

In an exhibition that pivots around so tender a subject as the AIDS crisis, Francis McWhannell finds warmth, sophistication, and an exhortation to reflect and to learn.

In an exhibition that pivots around so tender a subject as the AIDS crisis, Francis McWhannell finds warmth, sophistication, and an exhortation to reflect and to learn.

I sit in the gloomy, almost oppressive environment of the Blumhardt Gallery at the Dowse Art Museum, in which a small but dazzling piece of curatorial handiwork is on display. Beneath me is a bench covered in pale-green vinyl, patterned with spots that are rough to the touch. The surface feels non-slip. It would not be amiss on the floor of a bathroom. I quickly think of urinals and just as quickly feel a flush of guilt for coming up with so stereotypical an association. Curated by Simon Gennard, the 2017 Blumhardt Foundation/Creative New Zealand Curatorial Intern at the Dowse, Sleeping Arrangementscentres on a series of quilts made by renowned textile artist Malcolm Harrison (1941–2007). These works provide a departure point for a meditation on the ‘AIDS crisis’ of the 1980s and ’90s, and on queer histories in Aotearoa more broadly.

Before visiting Sleeping Arrangements, I resolved to carry out as dispassionate a critique as I could manage. Once inside the exhibition, I worry that my mission is folly.

Heavy subject matter, and not a little daring. Although he is gay, Gennard is too young to have had any direct experience of the crisis. For queer people, AIDS is (quite understandably) a potent trigger, being a cause of both tremendous human loss and – as Susan Sontag famously noted in AIDS and Its Metaphors– a further stigmatising of the already stigmatised. Shows dealing with the illness have come under close scrutiny in the past. When, in 2015, openly gay gallerist Michael Lett reimagined Implicated and Immune, a 1992 exhibition at the Fisher Gallery (now Te Tuhi), mainstream critics were mostly positive; Artforum, for instance, included the show as one of their ‘critics’ picks.’ Some members of the local queer community, however, charged Lett with trendy revisionism, reading the inclusion of artists from his stable in place of previous participants as opportunistic, rather than an attempt to pay homage to the original exhibition by picking up on one of its central concepts: allyship.

Before visiting Sleeping Arrangements, I resolved to carry out as dispassionate a critique as I could manage. Once inside the exhibition, I worry that my mission is folly. Born in 1985, at the outset of the AIDS crisis, I too lack direct experience. Worse, I’ve proved inadequately sensitive in the past. Discussing THE BILL, a multi-part exhibition organised by Artspace and other Tāmaki Makaurau galleries in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Homosexual Law Reform Act 1986, I referred to a man in an image by the inimitable Fiona Clark as an ‘AIDS victim,’ ignorant of the agency-robbing effect of my choice of words. My impartiality is compromised. I know Gennard and one of the artists personally, and I am bound to give them the benefit of the doubt. A key Harrison work, AIDS Quilt Dedicated to Simon Morley (1991), is owned by my uncles, Tim McWhannell and his partner of decades Terry Stringer. Reading the attendant wall text, I discover that the work was commissioned by a family friend, Rob Calder.

The normality of queerness was never questioned at home. And yet, for much of my youth, I didn’t want to be gay.

In addition to being tethered to the show through multiple human connections, I am deeply touched by Sleeping Arrangements. It speaks immediately to my complicated relationship with my queerness. In so many ways, I have been tremendously fortunate. First, I have lived through a period of rapid and radical improvement in the experiences of queer people in Aotearoa, and especially gay white men like me (when one considers how slowly conditions are changing for women, Māori and people of colour, the pace is nothing short of astonishing). Second, I have always enjoyed the support of my family. The son of an actor and artist, I grew up surrounded by queer people and allies. In addition to my ‘gay uncles,’ I have ‘lesbian aunts.’ I dare say a head count of my parents’ friends would reveal as many homos as straights, perhaps more. The normality of queerness was never questioned at home. And yet, for much of my youth, I didn’t want to be gay.

*

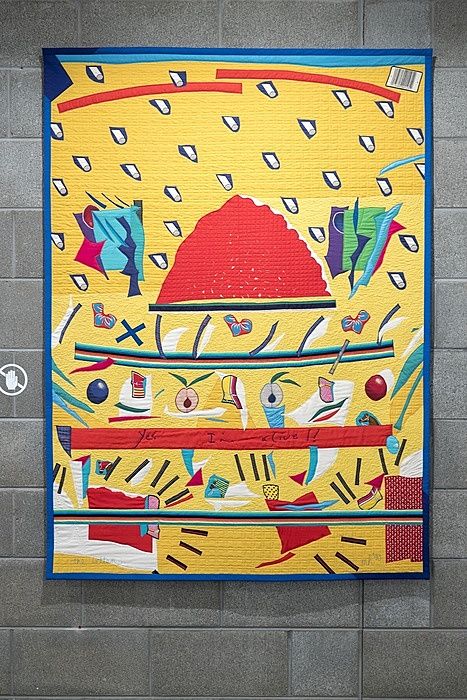

I hover in front of a Harrison quilt called The Letter (1990). Scrawl-stitched across a band of red is the triumphant phrase “Yes I’m alive!!” The heady colours of the work pulse in the low light. I spy a piece of fruit and, unbidden, images of childhood swim into my mind. Playtime at a Grey Lynn Primary School with a dwindling roll. My first class photograph. How proud I was of my pink trousers and the fact that the girl next to me was wearing the same sneakers. I was a stereotypical poof: gentle, ‘feminine,’ enamoured of fabrics and all things shiny. Five-year-old me would have been wholly entranced by all this vibrancy and softness, would almost certainly have started touching the quilts. I was, inevitably, bullied at school. I appear to have blocked out quite a few experiences, but I have a particularly clear recollection of being ‘outed’ at intermediate school as a long-time cross-dresser, by a girl who had gone to kindergarten with me and remembered that I had worn dresses and skirts by preference.

As puberty hit, I did a pretty good job of repressing a queerness that must have been glaringly obvious to all who knew me well. I abandoned dreams of becoming a fashion designer, began wearing skateboarder attire, despite not knowing the first thing about skating (it was the early 2000s). I forgot how much more comfortable I was in clothing that wasn’t made for boys. I elected to go to a relatively conservative high school, Avondale College, which boasted more than 2500 students, a massive and active Christian movement, but no visible queer presence. I have a sharp memory of joining in on a conversation about the aberrational nature of homosexuality (“I just don’t understand it at all”), betraying my family, friends, and of course myself. It took a year-long exchange away from Aotearoa for me to come to terms with being gay. I came out at 18, albeit somewhat tentatively, telling my mother, “I’ve fallen in love with someone, and he’s a man.”

I watch shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race with a mixture of relief and envy, wishing I had been born a little later, wondering how else I might have performed my self were I to have rejected hate, rather than bending to it.

Things changed fast – for me and for the wider community. By and by, people stopped called me ‘faggot’ in the street. A few years ago, I found out that a ‘Rainbow Club’ had been established at Avondale College. Today, I see young gay people, practically children to my eyes, holding hands and kissing in central Auckland. Social media, for all its problems, facilitates solidarity. I watch shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race with a mixture of relief and envy, wishing I had been born a little later, wondering how else I might have performed my self were I to have rejected hate, rather than bending to it. At the same time, I try not to forget my position of relative privilege. Unlike people I have met from other countries, I have never really feared for my life because of my sexuality. Unlike my current partner, I have never faced rejection from my whānau. Unlike any number of people I have not met, I am comfortable and confident enough to live and to speak about my queerness. Indeed, I struggle to imagine not being so.

*

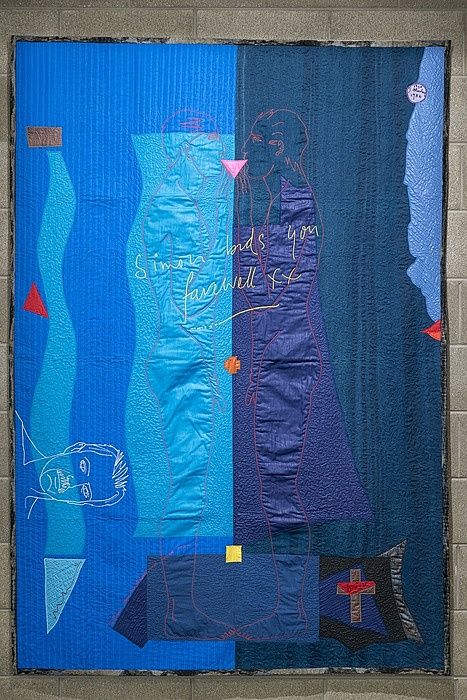

The Morley quilt is dominated by a pair of naked men, their red outlines burning through a background of blues and purples. Strung between their mouths is a glowing pink triangle. In the lower right-hand corner is a cross, draped with a cloth labelled ‘h.i.v.’ Marriage equality is surely the big public queer achievement of recent years, here as elsewhere. But it does not speak especially loudly to me, no doubt because one of the liberating aspects of my queerness is electing not to participate in ‘heteronormative institutions.’ More exciting are developments surrounding HIV/AIDS, which has hung like a dirty winter cloud over my entire sex life. Drug treatments are now available that yield an ‘undetectable viral load,’ making people who are HIV-positive effectively negative. The prophylactic PReP lately received selective government funding. The disease is no longer a death sentence; it is ‘manageable.’ We are, perhaps, on the verge of shaking off one more major stigma.

In an attempt to reclaim some measure of objectivity, I go back to the start of Sleeping Arrangements, begin reading the texts more closely, try to reinvent myself as a party at once more and less interested. My impression is that Gennard negotiates his dicey chosen terrain with exceptional intelligence and elegance. Knowing his deep dedication to his research and writing, I suspect he was at pains to ensure that his curatorial approach was maximally careful, sensitive. Yet his writings, including a truly superb catalogue essay, are not weighed down by caution. If Gennard clawed at his hair trying to get his phrases just so, little to no anxiety finds its way into the experience in the gallery. Harrison – who never ‘came out’ publicly, but whose sexual preference was something of an open secret – is handled with a deceptively easy sophistication.

It is important to remember that for most of Harrison’s life, the artist was legally bound to silence.

Harrison’s quilts abound with representations of men. They are recognisably homoerotic. But they are not festooned with strident sexual imagery of the sort employed by more radical queer artists of the same generation, such as Robert Mapplethorpe or, closer to home, Paul Johns. The Morley quilt, the most overtly gay work on show, was originally intended to be woven into a larger quilt, a context in which individual authorship would have been largely invisible. Gennard alludes to the possibility that Harrison’s ‘reticence’ was a product of the different moment in which he lived, noting, “It is important to remember that for most of Harrison’s life, the artist was legally bound to silence.” But he also suggests, compellingly, that the quilts might be thought of as calculatedly evasive, exemplars of what Nicholas de Villiers has termed ‘queer opacity,’ a strategy that refuses full disclosure and explicitness, embracing instead insinuation, slipperiness. The artist’s complexity is enhanced, rather than diminished.

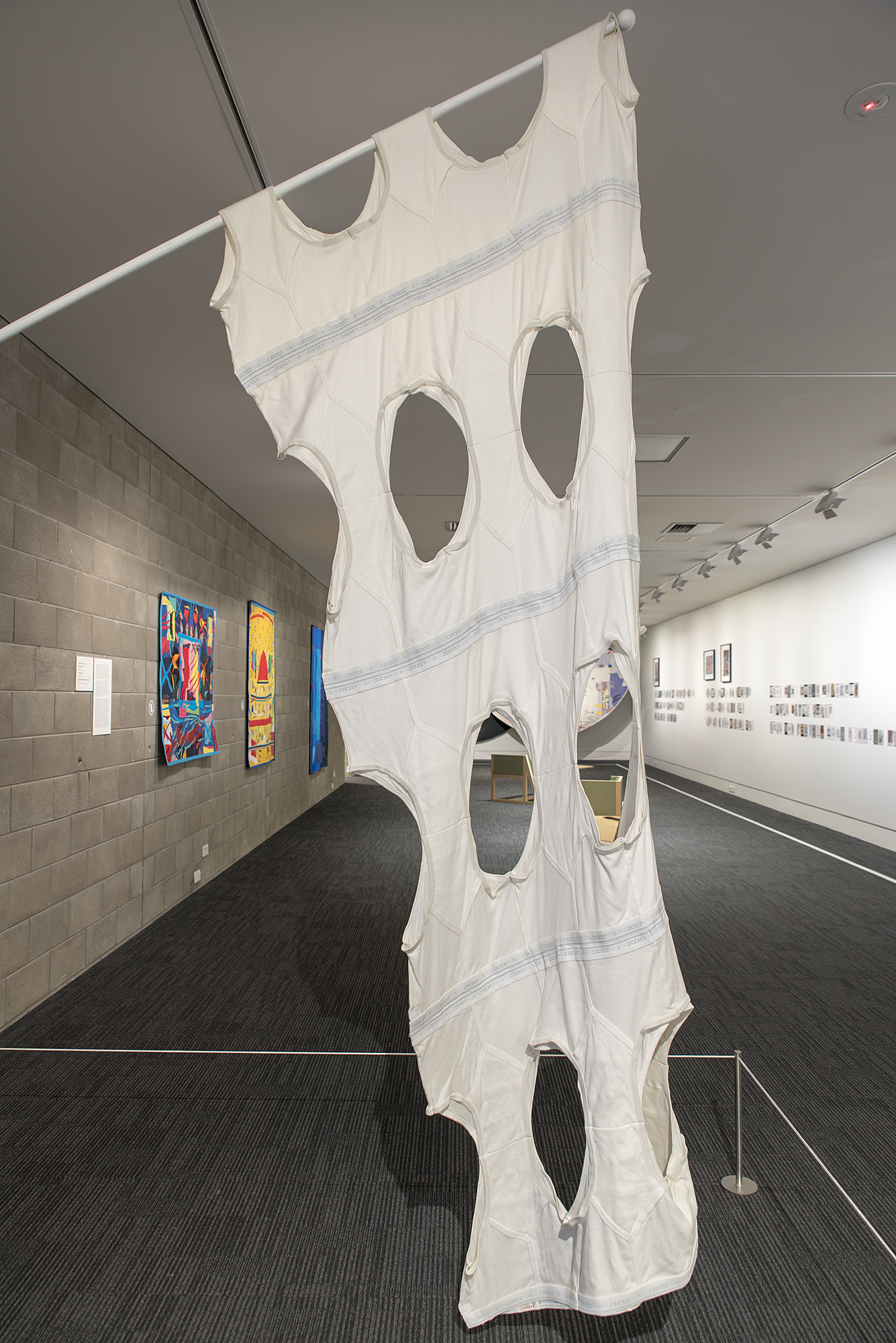

An alternative approach to Harrison’s discreetness is presented by the somewhat younger Grant Lingard (1961–1995), who died of AIDS-related complications. Gennard observes that Lingard’s Flag (1994), composed of white Y-front underpants, is “unapologetically political.” The artist did not intend the work to be equated with the white flag of surrender, describing it instead as “a small Up Yours, victory for me the artist.” The monumental scale of the piece, intensified by the closeness of the gallery space, immediately puts me in mind of flags used to claim territory or territorial victory. There is an echo of Joe Rosenthal’s Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jima (recently reinterpreted as a pride image by the well-named Ed Freeman), but with the Stars and Stripes replaced by a patchwork of garments immediately connoting dicks and arse.

The pairing of Harrison and Lingard is inspired. The use of fabric in both cases implies closeness to the body, cueing intimacy, sensuality and sex, indirectly but powerfully. As Gennard indicates, the works are united not only materially, but also by a certain quality of ‘coded-ness.’ Harrison’s Night Swimmer (1991), for instance, includes several male-looking heads superimposed with lines or crosses that quietly suggest lives scrubbed out, whether through death or through processes of moving on from failed relationships. The title is especially enigmatic. It sounds like a euphemism, but I can’t pin one down. I am reminded of a reference in Witi Ihimaera’s 1995 novel Nights in the Gardens of Spain to evening visits to the Tepid Baths in downtown Tāmaki Makaurau. I think, too, of a night-time beach swim I once took with a boyfriend, a situation that should have been unutterably romantic, but was in fact marred by a constant anxiety that swimming in the dark is practically begging for trouble.

Equally, white briefs have long loomed large in the gay imagination, even achieving fetish status.

Flag speaks loudly to gay male audiences. Gennard notes that, today, the presence of Jockey underpants immediately recalls the brand’s strikingly homoerotic advertising campaigns involving those icons of masculinity, rugby players. Equally, white briefs have long loomed large in the gay imagination, even achieving fetish status. In a 2017 series of photographs by Gui Taccetti, similar underpants feature as fixtures of gay sex ritual, all the more erotically charged for their apparent grubbiness and smelliness. In Flag, the garments are clean, but they might otherwise be impregnated with body fluids – intoxicating or horrifying, depending on your perspective. Lingard’s banner contrasts with and complements Harrison’s four works perfectly, answering dazzling ornateness with stark elegance, coy meditation with proud irreverence. Together, this small group of works does a remarkable job of suggesting the plurality of gay male attitudes and experiences in the recent past.

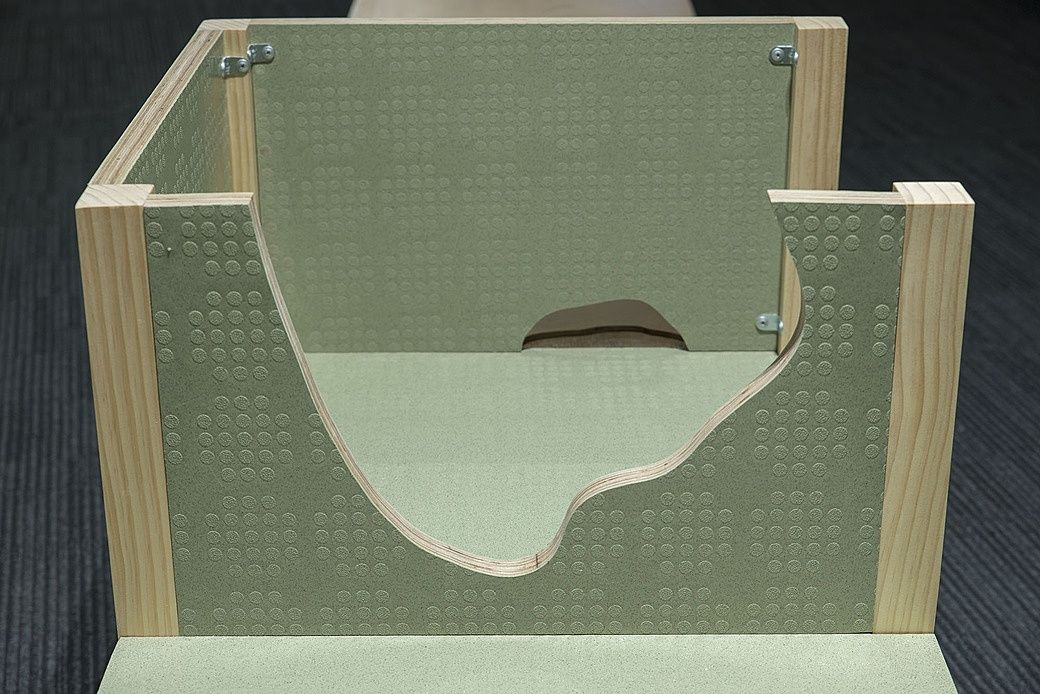

The other works included in Sleeping Arrangements are by living artists, who consciously address recent history from the position of those growing up in its wake. Zac Langdon-Pole (b. 1988) presents two associated works: a poem originally recited by his uncle, Brendan Pole, to members of his family shortly before his death from AIDS-related complications; and a ‘gloss,’ comprising extensive quotations from the likes of Judith Butler, Franz Kafka and Anne Sexton, which load the poem with additional interpretive potential. Micheal McCabe (b. 1994) has created a pair of benches, providing a site for reflection within the fabric of the exhibition. The postmodern vibe of the furniture, with its overall rigidity punctured by organic cut-outs, resonates with Harrison’s distinctly ’90s aesthetic, one that has lately come full circle and feels very much in sympathy with the design and fashion of the present moment.

Finding myself alone in the exhibition space, I begin to read the poem aloud, the better to capture it, make sense of it.

Although they make extensive use of verbal language, Langdon-Pole’s works are no more explicit in message than those by Harrison and Lingard. As the artist’s sister, Georgina, has noted, the poem in My Body … (Brendan Pole) (2015) has been reconstructed by the artist through conversations with his mother, Cathy Pole, who heard it first-hand. The text is made up of decorative letters taken from a compendium published in 1984 (the year of the first recorded case of HIV in Aotearoa). The presence of ‘historiated initials’ gestures towards the complex and manifold narratives that lie behind the relatively concise poem. The overall ornateness of the letters makes the text difficult to read, suggesting the processes of corruption that have come to bear on it between its utterance in the early ’90s and its ‘documentation’ in 2015, as well as the sense of a meaningful but disrupted connection between nephew and uncle.

Finding myself alone in the exhibition space, I begin to read the poem aloud, the better to capture it, make sense of it. The pacing is necessarily slow, producing an effect of laboured hesitancy that feels achingly apt: My body / A clot / Of inscriptions / Flayed by / Sacred hunger / Clinching nothing. The text speaks across the bunker to Harrison’s works, inscribed as they are with phrases that are similarly lush and enigmatic. In Eclipse (1991), bracketing a creamy male nude with pink nipples and pale peach genitalia, is a verse that resonates with body and land: Softened shapes of mountains loom / winging high across sighted haze / shapeless in their barbarities / constructing sites for sun to laze. I think, too, of Kendrick Smithyman, writing of the sparseness of much everyday communication in New Zealand: We communicate, in the resonant silences / between my words. Also, are your words.

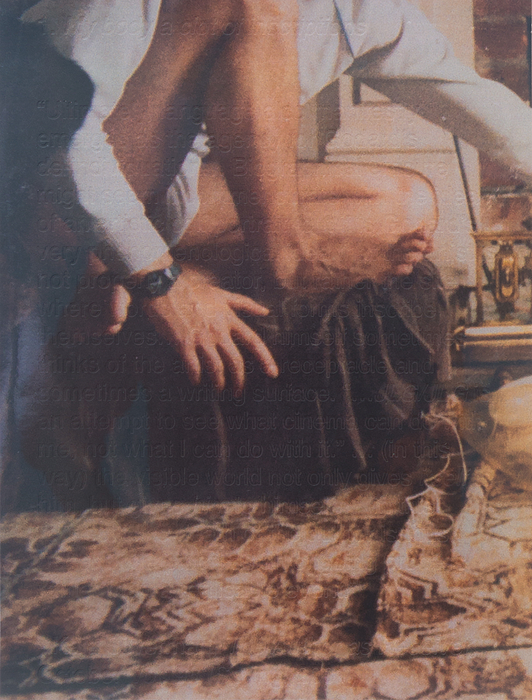

In order to overcome the glossiness of the images themselves, and the reflective quality of the glass that protects them, I have to oscillate before the display.

The inclusion of Gloss (1–6) (2016) drives home the point about the complexities of language, while also adding a note of academic depth, drawing attention to the importance of critical theory in the development of contemporary notions and understandings of queerness. Enlarged fragments of a single image taken from a family album have been debossed with the quotations. Again, the texts are difficult to make out. In order to overcome the glossiness of the images themselves, and the reflective quality of the glass that protects them, I have to oscillate before the display. Again, I feel compelled to read aloud, engaging in a process of retrieval that feels ritualistic, involving dance and incantation, while also reminding me of the deciphering of handwritten letters, a demanding process that involves actively trying to lose oneself in the world of another.

McCabe’s waiting outside (2018) assists a similar practice of losing oneself in contemplation. Like the works of Harrison and Lingard, the benches are tactile; they invite touch. They, too, are imprecisely evocative. The title puts me in mind of the experience of waiting at a sexual health clinic prior to having bloods taken or, worse, waiting for the results of a ‘fast test’, dwelling on the possibility, however slim, of being found HIV positive. Gennard notes that the seats are not especially comfortable, but they also visibly invite visitors to linger in the space of the exhibition, to reflect on its content and its possible implications. The vinyl on the benches gives them the faint feel of a community facility, one that is made to endure through countless cycles of clients. On them, we are all in it together. They stress parity, oneness.

Glancing over at My Body … (Brendan Pole), I notice a capital A formed by a knot of human bodies and am reminded of a newspaper article by David Famularo in the Dominion Post (12 September 1997). In it, Harrison discusses his interest in art of the Middle Ages, suggesting that it is “based on purpose and not the ego (of the artist).” It occurs to me that Sleeping Arrangements operates in a similar way. While it does honour to the artists involved, recognises their achievements, it shies away from making claims about their importance. Harrison and Lingard are not – as they so easily might have been – positioned as overlooked or undervalued figures. Nor is there any sense that the show is courting attention. It emerges as at once bold and unassuming, daring and gentle. Its mission is beyond itself.

I feel summoned to talk to aunts and uncles by blood and otherwise; to learn more about the hardships and losses experienced by queer people before my birth, but also the pleasures and gains; to develop a better sense of the rhythms of uncertainty, rebellion and kinship that pulse through the queer experience still.

For much of my life, I have shied away from avowedly queer groups and events, partly because I have deemed my sexuality a single aspect of my person, partly because I have enjoyed the backing of a family that has allowed me that understanding, and partly because the world has been growing safer for me, rendering queer support structures less immediately essential. However, as I get older, and better recognise the changes that have taken place during my life so far, questions of the collective assert themselves more strongly in my mind. Sleeping Arrangements encourages me to reflect and to engage more deeply. I feel summoned to talk to aunts and uncles by blood and otherwise; to learn more about the hardships and losses experienced by queer people before my birth, but also the pleasures and gains; to develop a better sense of the rhythms of uncertainty, rebellion and kinship that pulse through the queer experience still.

Subtly, warmly, and without finger-wagging, the show advocates for the telling of queer stories, the learning of queer histories, the shoring up of queer communities and values. Gennard writes that “together, these artists engage in an intergenerational conversation about sexuality’s ambivalence and complications.” And so they do. But Sleeping Arrangements also instigates broader conversations, not only among the gay men like me who are its logical primary audience, but also among any people who happen to stop by. Independent of a specialised context, like a pride festival or a symposium on queerness, the show represents something we could do with a bit more of. I sit in the gloomy, almost oppressive environment of the Blumhardt Gallery at the Dowse and feel uncommonly full of hope.

Sleeping Arrangements

The Dowse Art Museum

21 April – 19 August 2018

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.