The Future of Craft in Aotearoa

Lana Lopesi in conversation with Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Karl Chitham and Anna Miles about the possibilities of a fresh approach to the word and the idea of ‘craft’.

Lana Lopesi in conversation with Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Karl Chitham and Anna Miles about the possibilities of a fresh approach to the word and the idea of ‘craft’.

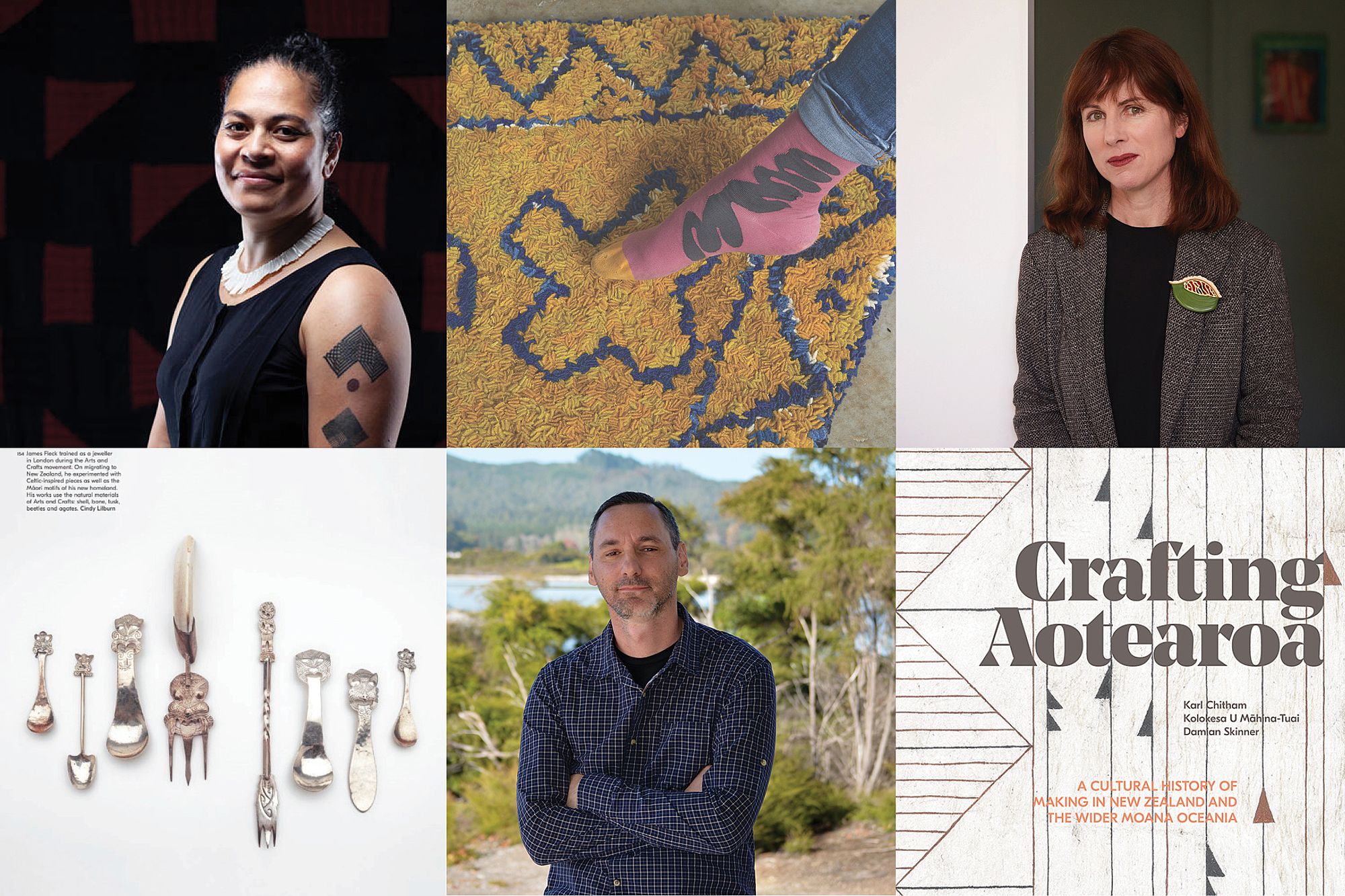

Last year the landmark book Crafting Aotearoa: A Cultural History of the Handmade in New Zealand and the Wider Moana Oceania was released by Te Papa Press. The love child of Damian Skinner, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai and Karl Chitham, Crafting Aotearoa was the result of many years of work and many more conversations, and when reading the book it’s clear to see why. Expanding the limits of what the word ‘craft’ can encompass, the book “proposes a new idea of craft – one that acknowledges Pākehā, Māori and wider Moana Oceania histories of making, as well as diverse community perspectives towards objects and their uses and meanings”.

In addition to writing by Skinner, Māhina-Tuai and Chitham, another 66 contributions by various community members and experts add more perspectives to what is a crafting history of this place. To get some more insight into what craft in Aotearoa actually is, the relentless (and somewhat tired) devaluing of craft compared to art, its disintegration from our educational systems, as well as what the future of crafting in Aotearoa might look like, I sat down with Crafting Aotearoa co-editor and co-founder of cultural academy and consultancy Lagi-Maama, Kolokesa U Māhina Tuai; fellow Crafting Aotearoa co-editor and Director of The Dowse Art Museum, Karl Chitham; and art dealer and Senior Lecturer in Visual Arts at AUT, Anna Miles.

Lana Lopesi: I know there a few big issues that we’re looking to discuss today, but to start I’m interested to know, what is the most memorable piece of craft that you’ve experienced recently?

Anna Miles: I’ve been thinking about Vita Cochran’s rag rugs that she exhibited at the gallery last year. I am fascinated by what she set out to do. She chose to make rugs from modernist paintings in which the painter would never had made the innovations they made in their work, had they not been steeped in the world of textiles and domestic life. So there is something incredibly defiant about her view; she was proposing a very different view on the significance of the textile arts, making you think about that time in history in which tapestries were more valued than paintings.

Vita Cochran, After Paintings, 2019, installation view, Anna Miles Gallery.

Henri, 2019, parallelogram, 980 x 700mm (total length including acute corners, 1280mm).

Henri Matisse, The Pink Studio, 1911.

What is difficult to account for is just how much potency those rugs of Vita’s acquire because of her makerly passion and fastidiousness. They are materially amazing items and are quite discombobulating. I suppose they make me think of a really important aspect of craft, which is the way it evades the explicit; its power can’t easily be accounted for.

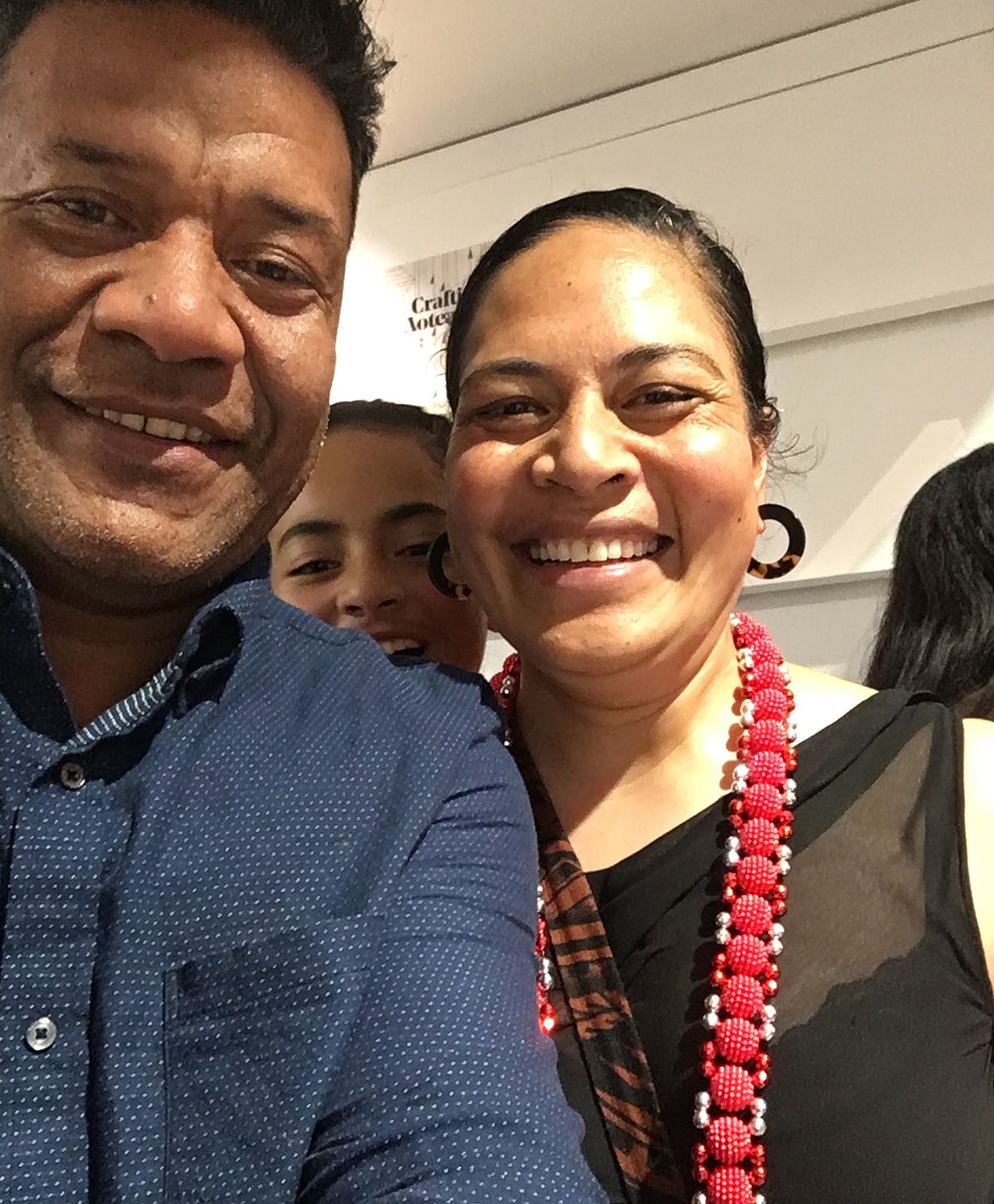

Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai: For me it was a red beaded ‘ula, which I was gifted when we had the Auckland launch for Crafting Aotearoa. It was made by Tanuvasa Esekia Taituave, the father of one of my Sāmoan best friends. I went to visit my friend Marisa at her house in Ōtara and I admired these beaded ‘ula that were hanging in and decorating her house. I asked her who had made them, and she replied that it was her dad. He had a stroke a few years ago and is now retired, and for him it’s quite a soothing thing to do. Marisa couldn’t come to the Crafting Aotearoa launch, but her husband Kiki came and gifted me an ‘ula, which was bling red. He said, “I know it’s blingy,” and I was like, “It’s very Tongan.” Tanuvasa had purposefully made it in the colours of Mate Ma’a Tonga.

Karl Chitham: I’m surrounded by a lot of objects, and I have to think very carefully about what ones have resonance for me. But actually, it’s one of the items that Kolokesa and I are going to have in an upcoming show that we’re working on (Ā Mua: New Lineages of Making, showing at the Dowse, 4 April – 26 July). The piece is called Te Nehenehenui and was made by Eugene Kara. I saw it in an exhibition at Waikato Museum as part of the Puhoro ō Mua, Puhoro ki Tua exhibition, and it stopped me in my tracks. It’s the first piece that I got really excited about it. It was the style of carving, the approach he had used to its design, and the way that relates to the story. It was about King Tāwhiao, and while I’m not from there and it’s not my story I felt like it signalled a shift in carving practice that wasn’t just about conforming to international sensibilities for the market, or a Māori sensibility for it to go into a marae project. It was a stand-alone piece that was about this connection with the whenua.

I don’t hold craft in any weird, low kind of hierarchical position. I understand everything as craft when it’s done very well, including art.

LL: Listening to you all talk about these items, what I can hear is the specific resonance of something which feels almost like an anchor point for a wider love of craft. What was it specifically that got you into the work that you’re doing now? And, more generally, what actually is craft in Aotearoa?

AM: I was really fortunate to go to primary school in the mid-70s, in a time in which the educational adventures that had been initiated by Clarence Beeby were still very much alive in the culture. And that was a time in which art was not separated from craft in our experiences as students. In fact, it dominated the curriculum. In this context, making in New Zealand wasn’t simply a leisure or recreation activity. It was utility as much as pleasure and it occurred in a highly protected economy.

Obviously I don’t hold craft in any weird, low kind of hierarchical position. I understand everything as craft when it’s done very well, including art.

While I’m accepting of the word ‘craft’ now, what I’m not accepting of is this hierarchy where what they make is ‘traditional’ or ‘craft’ and not contemporary

KMT: In the work leading up to Crafting Aotearoa I was really anti the term ‘craft’. The work of the makers I was working with was also described as craft, and while I’m accepting of the word ‘craft’ now, what I’m not accepting of is this hierarchy where what they make is ‘traditional’ or ‘craft’ and not contemporary, where it might be shown in a museum but not a gallery.

I had never worked with Damian [Skinner] before, so when he proposed the Crafting Aotearoa project to me, my only question was, are you open to me critiquing the word ‘craft’ and he said yes. And I replied, okay I’m in. So if we were successful in what we aimed to do with Crafting Aotearoa, then craft in Aotearoa is multi-faceted, multi-perspective, multi-media, handmade as well as human made.

KC: I grew up in a family that didn’t have any making practices, at all. It was a lifestyle that was a bit devoid of aesthetics. And in that sense, I felt like I was a bit removed from that kind of history that you have Anna, or even the kind of history that you have Kolokesa. Then I did my degree in contemporary jewellery – I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I actually only chose it because I had a friend that was doing the course and I couldn’t decide what else to do, so that was really my introduction to craft. But from that point it’s become a part of my life.

In terms of what craft is now, I do still struggle with the term – not because it’s a bad term, but because of the expectations that other people put on it. I remember having a conversation with Maggie Gresson from Artists Alliance and she did a programme called ‘The Dirty C Word’ and I was like, is it dirty? So that really started me questioning the terminology.

When we started working on Crafting Aotearoa and talking about the word ‘craft’, we quickly started to realise that the distinction was about the relationship with studio craft and fine art, and I remember Anna saying quite firmly, in one conversation, that she’s “so sick of the debate, there isn’t a debate”. And I remember thinking, well from our perspective there isn’t but people still have this hang-up about the term. So, when we were talking about the book and how to talk about craft, it became very much about the handmade, and makers of excellence and quality, and not so much about the word.

All of these practices can be craft, all of these practices can be art, all of these practices can have whatever name you assign to them, but these are all amazing practices.

Damian and I tested some of our ideas at a symposium in Dunedin (which was an early version of the introduction to the book) and a Māori weaver in the audience was so angry. She stood up at the end, shouted at me and said, “We do not make craft.” I thought, wow, that’s a really strong reaction to a word. That was really the catalyst for us to push home that all of these practices can be craft, that all of these practices can be art, that all of these practices can have whatever name you assign to them, but that these are all amazing practices. And that’s how we move forward.

AM: The book champions the spaciousness of the category. I mean that is probably one of the most significant things it can achieve. Its inclusivity makes it a very powerful thing.

KMT: While writing Crafting Aotearoa, it was really important for me to expand the handmade to include a human-made aspect, which includes things like oratory and knowledge about dressing someone. There’s an element of craft in knowing how to wear something, what materials to use; it’s knowledge and skill that not everyone has and which needs to be acknowledged. The question was how you deal with these practices, which are temporal but also have been crafted. So, in the end I had no issue with the term ‘craft’, but also because I had felt comfortable that we had really tried to explore it and define it and elevate all the practices that can be included.

AM: Well perhaps the book offers something like that innovative educational programme [previously mentioned] that was launched when people like Doreen Blumhardt were specifically hand-picked to become specialists and go out into schools all around the country. You’ve done something that is both powerful and very positive about craft. I suppose I’m really interested in where the conversation is going now that this has landed. I’m really interested in the objects, I’m really interested in the critical force that they have. I’m interested in those objects in your book because they are very potent things, their qualities and their criticality cannot be easily accounted for, and that’s why I think craft is critical and there’s a lot of work to be done in terms of actually, really, talking about the objects and making cases via the objects.

I am interested in the way in which in every aspect of education, from primary to tertiary, we have witnessed an evisceration of craft (and art – I’m not going make that distinction) from the curriculum. One of the interesting things I found in Crafting Aotearoa is that you historicise the introduction of craft to formal education from primary school up, but no one has written the history of its degradation, how the wheels fell off, how this whole innovative aspect of education in the country has died, and it has died. I talk to tertiary educators around the world and they’re constantly talking about their students’ mental health. We’re constantly talking about wellbeing but our education has become less ambitious.

KC: It’s also happening within the wānanga system. I find that, in some ways, more disturbing because I know that mainstream education is cyclic, things do come and go, but in the wānanga system its talked about a lot that all the art forms associated with the marae are essential to our knowledge and understanding of toi Māori, and if those things are falling off and not being replaced then there are serious issues.

There are conversations happening about this everywhere. In our national art gallery directors’ network, the impacts of this educational deficiency are something we talk about every time we meet, and I feel very anxious about that.

My problem is whose definition of art are we advocating for? How can we fill in the knowledge gaps to understand the diverse communities we have?

LL: I’m interested, then, in other spaces in which we learn and pass on making practices. A lot of the makers you work with, Kolokesa, sit outside of mainstream education.

KMT: I understand, Anna, where you’re coming from, and totally get it. But it also frustrates me because it feels like we’re operating in this one mode, so how can we approach it from a different way? For example, in primary school, how can we acknowledge where each child has come from, and the living communities that they’re part of, and the making practices that come with that, because it all links to that idea of wellbeing. There’s currently, today, not enough recognition and awareness that our living communities in all these different contexts are thriving. How can we create awareness around the way that people continue their practices and protocols, and pass them down, how do we create awareness around that, and how can that inform some of the bigger policies?

It’s like the current conversations and advocacy around the arts; my problem is whose definition of art are we advocating for? Because at the moment people are operating on current Western understandings of what art is, so how can we fill in the knowledge gaps to understand the diverse communities we have? In a way this is similar to what we did with Crafting Aotearoa, because only then can you genuinely advocate.

We’ve all got so much to gain, and it seems to me that craft is one way we can easily share things, knowledges and culturally resonant traditions.

LL: Throughout this conversation – when we’ve talked about Crafting Aotearoa and craft in Aotearoa more broadly, as well as what the future of craft looks like – this idea of being multi-modal or multi-perspectival, expansive rather than limiting, keeps coming up. So how can we work toward this multi-modal craft future?

KC: Conversations like this are important, and that was something that did come out of the process of the book rather than the book itself. The initial conversation, which was seven years ago, with significant people in the world of craft, was predominantly a Pākehā space. While we were doing the book, we had lots of discussions about how craft is not only a Pākehā space, and about what that space could be. And so, we then had meetings with people from the Moana and then again with some Māori makers. And that was really what we did; had many, many, many discussions with many groups, about the use of the word ‘craft’ but also just about craft practices generally, and I think it did come back to what Kolokesa was talking about. The practices that exist already are there for a reason – they’re used all the time and they’re the things that people value. So, putting more emphasis on those things is important. In the book we do talk about non-traditional craft spaces (from a Western perspective). Those conversations are a part of the next step, because if you don’t privilege them by talking about them, then how do they get a profile?

I agree with what Anna is talking about as well. It’s important to think about mainstream education and to put some emphasis on craft and making, because it’s about our ability to talk about that out in the world, and not everybody has access to making practices.

KMT: Yeah access is a big thing. Haruhiko Sameshima and Mark Adams [as Studio La Gonda] were the photographers for Crafting Aotearoa. And one of the things that we talk about [in the book] are contexts within churches, like White Sunday, which is such a rich space where you can see the latest trends of making and adornment. Haru took the photograph in the book for White Sunday and he said that over the many years that he has been photographing he had never had access to come into a space to see this. And yet, it’s just down the road. So yes, access is a privilege, but we need to do it in a way that is safe for the community. We need to create spaces in which we can highlight what’s happening and say, hey here’s the richness of Aotearoa. Otherwise it’s going to be the same conversations, the same terminologies.

AM: You’re talking about sharing, and that’s a great example. We’ve all got so much to gain, and it seems to me that craft is one way we can easily share things, knowledges and culturally resonant traditions. Anni Albers wrote in 1965 that so far are we from actually engaging our tactile sensibilities that we just put the bread in the toaster, we don’t put our fingers in the dough. And I think we should all be putting our fingers in the dough together.

Feature image (clockwise from top left): Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Vita Cochran’s Henri, Anna Miles, Crafting Aotearoa, Karl Chitham and jewellery by James Fleck.

Disclosure: Lana Lopesi is on the Illustrated Non-Fiction judging panel of the 2020 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Given that she was commissioned to write a short essay for Crafting Aotearoa: A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the Wider Moana Oceania, she excused herself from any judging deliberations on this book.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Blumhardt Foundation. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.