From Each According To His Need: How Our Tax System Punishes the Poor

This week, guest writer Kyle Rainsford talks about taxation as social policy -and why ours is actually an antisocial shambles.

We don’t talk about tax very much on The Pantograph Punch —probably because unlike music, theatre or television, it doesn’t throw itself in our faces. Unlike a certain segment of TradeMe political subforum-dwellers, we still manage to sleep at night knowing that we part with it, but we don’t think in any depth about its role as a social mechanism beyond that. The other issue of course, is that tax tends to be written about in alternately boring and hysterical ways by most commentators, creating what is at once a tedious maze and a labyrinth of terrors to the ‘average working Kiwi’.

Thankfully, this week’s guest writer Kyle Rainsford has risen to the challenge…

We’ve got a pretty broad consensus that taxing the rich and feeding the poor is a good idea in New Zealand. While communism is now a dirty word, Marx’s maxim, “from each according to his ability; to each according to his need,” has survived Douglas and Thatcher.

And it has survived for pretty simple reasons. Capitalism denies those without cash access to food, shelter, education, and healthcare. Since leaving people to die isn’t morally palatable for most of us, people of most political persuasions agree that we should intervene to correct this basic injustice. (There is the notable exception of the ACT Party, whose members either believe charities will solve all poverty or that bootstraps nourish the underprivileged.)

Except we don’t, really. Although we implement programmes to redress some of the harm from being born into a poor family, we snatch much of it back with taxes. Our tax system is biased against the poor; it punishes those who can’t make ends meet and rewards the middle-class consumer.

Tax is important. The impact of taxing is just as important as the impact of spending. Most of us would be unhappy with a welfare system that gave money to Paul Holmes and John Banks. Our tax system misses the mark just as badly, yet no-one seems to know about it.

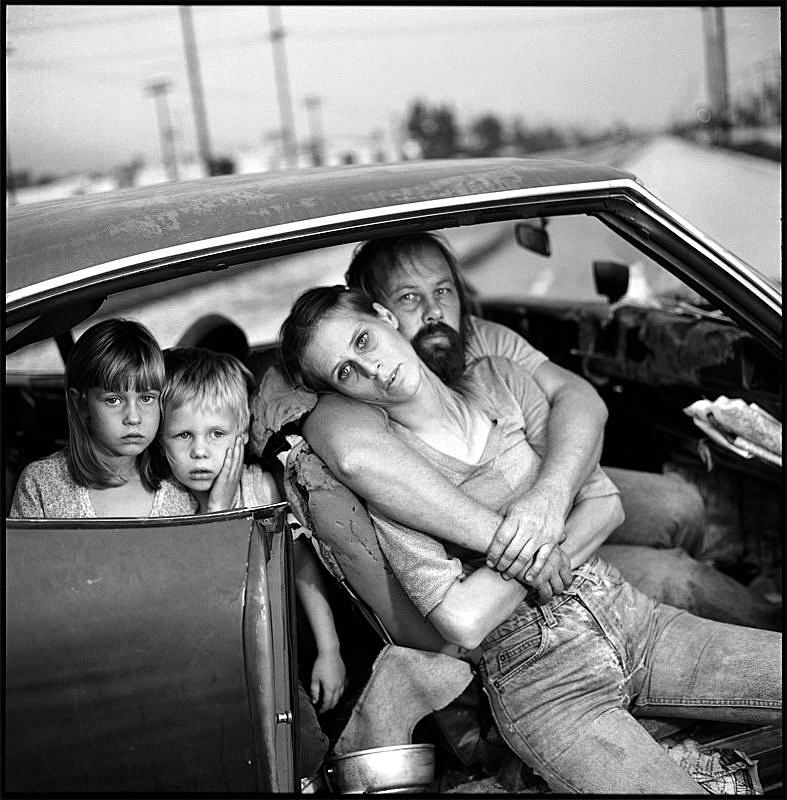

This clip art drastically oversimplifies the issues with taxation as social policy. Worse, it falsely depicts what you can type into a calculator.

We Giveth, and We Taketh Away

New Zealand is pretty good relative to most of the world at spending to relieve poverty. Our welfare, healthcare, and superannuation systems are laudable for what they say about our compassion and what they accomplish in mitigating the worst of human hardship. Relative to the rest of the world, we established certain ‘from cradle to grave’ commitments early and we meant to go on. Suggesting any of this be dismantled is a call limited to a few out on the lunatic fringe, while in the middle there’s an (occasionally grudging) acceptance that these systems are a must for a civilised society. We do shirk our obligations in some key ways, of course, and a lot of these involve targeting demographics that might otherwise benefit from these systems for the sake of populism. Think forcing solo mothers back to work when theire youngest child starts primary school, or cutting off their allowance to go into higher education. Or giving the young unemployed pre-pay cards rather than actual money and budgeting assistance.

More broadly, how we pay for these expenses undermines these achievements. We say that our tax system is “progressive”, meaning the rate of tax is lower on the first dollar of income each person earns than it is on the millionth. This makes sense, because if $1000 is all you earn in a year, it’s probably all going to go on food and rent. If you earn a million dollars, you can feed and shelter a few dozen people and still have money left over to buy yourself a new TV.

Tax systems that are progressive are better at ensuring that we aren’t depriving the poor of the very basic needs in terms of food, shelter and clothing for their survival. But progressive taxation also provides other benefits. It slows the growth of income inequality — which is correlated with higher prison populations, low maths and literacy scores, and social mobility. If you’re tired of reading and don’t mind the minor tangent, check out an excellent talk on this below by Richard Wilkinson.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cZ7LzE3u7Bw]

Progressivity is good. The other options are not so great. Flat tax systems - where each person pays the same percentage of tax no matter how much he or she earns - operate in a number of tax havens (small and stable territories that specifically make themselves into attractive places for rich people and big companies to relocate and retain money that would otherwise be taxed fair and square – think Luxembourg, the Cayman Islands – even the Cook Islands). It could be said that the tax systems of countries like Russia or Hong Kong also come close to the horizontal ideal, too. Not coincidentally, they each lack a modern welfare state of the kind we do in New Zealand, and income and wealth inequality runs rampant.

The only option worse than a flat tax system is a regressive tax system. Tax systems are “regressive” where the rate of tax decreases for those who earn more. Under this system, poor people pay more tax per dollar than rich people. Regressive tax systems abound in the history books alongside slavery and feudalism. They were repugnant to the notions of equality that flourished as democratic institutions flexed and asserted themselves. A regressive tax system represented a less visible but equally offensive way of denying social mobility, of ensuring a static regime of master and servant where the latter had no way of becoming the former. To that hoary old classical liberal cliche of ‘equality of opportunity’ (everything, anywhere – having the same chance to succeed) it was unthinkable. Outrageous.

And, surprisingly, modern New Zealand may have one.

Household basics (15% goods and services tax not pictured) at a Far North community foodbank in August 2012. (The Bay Chronicle)

You’ve got Progress, You’ve got Congress

Most liberals are passingly conversant with the expenditure side of this obligation. Yes, the New Zealander will say, let us provide a safety net for those who “fall on hard times”. (The euphemistic phrasing makes it sound as though no one is born into poverty.) We can probably all name half a dozen welfare schemes. But fewer of us could explain our tax system.

New Zealand has two main taxes: income tax and goods and services tax. Income tax is the tax most people are aware of. People pay income tax on money they earn, irrespective of what they do with it after that.

Here is our progressive income tax system in a nutshell: the first dollar of income everyone in New Zealand earns is taxed at 10.5 cents. So is the next, up to and including the fourteen-thousandth dollar. From dollar number 14,001 to dollar number 48,000, it is 17.5 cents. Above $48,000, the rate is 30 cents in the dollar, and we hit the maximum of 33 cents in the dollar at $70,000.

These numbers are misleading, because people often quote the highest income tax rate that applies to them, even though the majority of their income is taxed at a lower rate. A successful lawyer or New Zealand Herald columnist earning $100,000 a year pays income tax of only $25,000. Though she will quite happily tell you her marginal tax rate is 33%, she is only paying 25% of their income in tax.

But so far so good. Poor people pay 10.5%, rich people pay 25%. We’re still fulfilling our end of the social contract, right? Everything looks fair.

Not quite: the problematic part of our tax system is GST. As a “consumption tax”, everyone pays GST on things they buy to consume in New Zealand. Most countries (the United States excepted) have GSTs, but New Zealand’s is the harshest in the OECD.

Unlike virtually all other rich Western nations aside from Denmark and the Slovak Republic, our GST applies to basic food from the supermarket. Unlike Australia and Canada, our GST applies to transport. Australia’s GST is at 10%, and Canada’s is 5% — ours is 15%.

Why does it matter that our GST is particularly aggressive? It matters because GST is a regressive tax: poor people pay a higher rate of GST per dollar of income they earn than the rich do. Since our GST is especially harsh and especially high, it hurts poor people more than equivalent taxes do in other countries.

At first glance it might not seem right that a tax charged at a single rate — 15% — can affect the poor more than the rich. The same rate applies to everyone. But since people pay GST on goods and services they consume, and since poor people consume more of their income in a year than rich people do, GST ends up taking more of a poor person’s total income.

The figures are startling. The poorest decile of New Zealanders spends 105% of their income on goods and services that have GST. (The figure is more than 100% because the average person in the lowest decile borrows money to make ends meet.) The total tax bill for the poorest decile, if we take into account both income tax and GST, is a staggering 26%.

By way of contrast, someone comparatively well-off — earning, say, $50,000 a year — will actually pay less of her income in tax than someone in the poorest 10%. In fact, people earning $50,000 pay an average of 22% tax, the lowest rate across all earners in New Zealand. (After $50k, the percentage of her income a person pays in tax increases again.)

These figures show that New Zealand’s tax system is truly regressive. Those in poverty pay the most tax, but each dollar more a person earns is taxed at a lower rate. In some ways, this reflects neoliberal capitalist views on the social worth of taxpayers: poor welfare recipients are punished, while middle-class consumers are rewarded.

We can laugh, but there's not many Lucky Duckys in NZ right now.

The Worst of a Bad Lot

We are alone in our regressivity, and we should be ashamed of it. Effective tax rates for the very poor in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom are all much lower than ours. They all increase for higher incomes, whereas ours decrease.

They tax the rich more, too. The highest tax rates in all three countries are over 45%, and they tax capital gains (the gain from the increase in value of assets like property and shares) too. New Zealand’s highest rate is 33%, and we exempt most capital gains. Even the United States, not exactly a bastion of progressivity, has a more progressive tax system than we do. The poorest Americans pay about 18% federal tax, while the richest pay 30% or so.

Our tax system is shockingly unfair. This might be the result of New Zealand’s aggressive neoliberal reforms in the 1980s. Douglas reduced the tax rates for the rich and introduced GST, which disproportionately affects the poor.

The 2010 National budget compounded the problem. It increased the GST rate and simultaneously dropped the top income tax rate. While Key and English said the tax switch was “revenue neutral” (the same amount of money would come into the Treasury’s coffers each year), they did not mention the distributional and social effects of their cuts.

Proposals to address poverty in New Zealand, and policy questions about welfare, need to start with a consideration of the tax burdens poor New Zealanders face. A New Zealander moving from unemployment to employment faces one of the highest tax barriers in the OECD. When we hear stories about cleaners who have to work two or three jobs to keep their families fed, we should remember that one of the reasons this occurs is because New Zealand cleaners take home less pay, after tax, than cleaners in other Western countries.

There is a strong moral case that we should not tax the very poor at all. Labour made some tentative steps towards it in their 2011 campaign (by making the first $5,000 a person earns tax-free and removing GST on fresh produce, though it appears they will abandon both), and it has been a key plank of the Greens’ tax policy. But at the very least, we should all agree that we should not be punishing them.

We boast in New Zealand that everyone “gets a fair shake”. But the poor don’t. We tax them relentlessly, and don’t ease up until they’ve made it to the middle class — our tax system is a pretty big hurdle in the way of social mobility and genuine equality of opportunity. We’re not fulfilling our end of the social contract. It’s time we changed that.