Repositioning the Centre: Bepen Bhana's 'Frankie Goes to Bollywood'

Balamohan Shingade reflects on Bepen Bhana's latest exhibition and on the artist's refusal to relegate Indian New Zealanders to the margins.

Balamohan Shingade reflects on Bepen Bhana’s latest exhibition and on the artist’s refusal to relegate Indian New Zealanders to the margins.

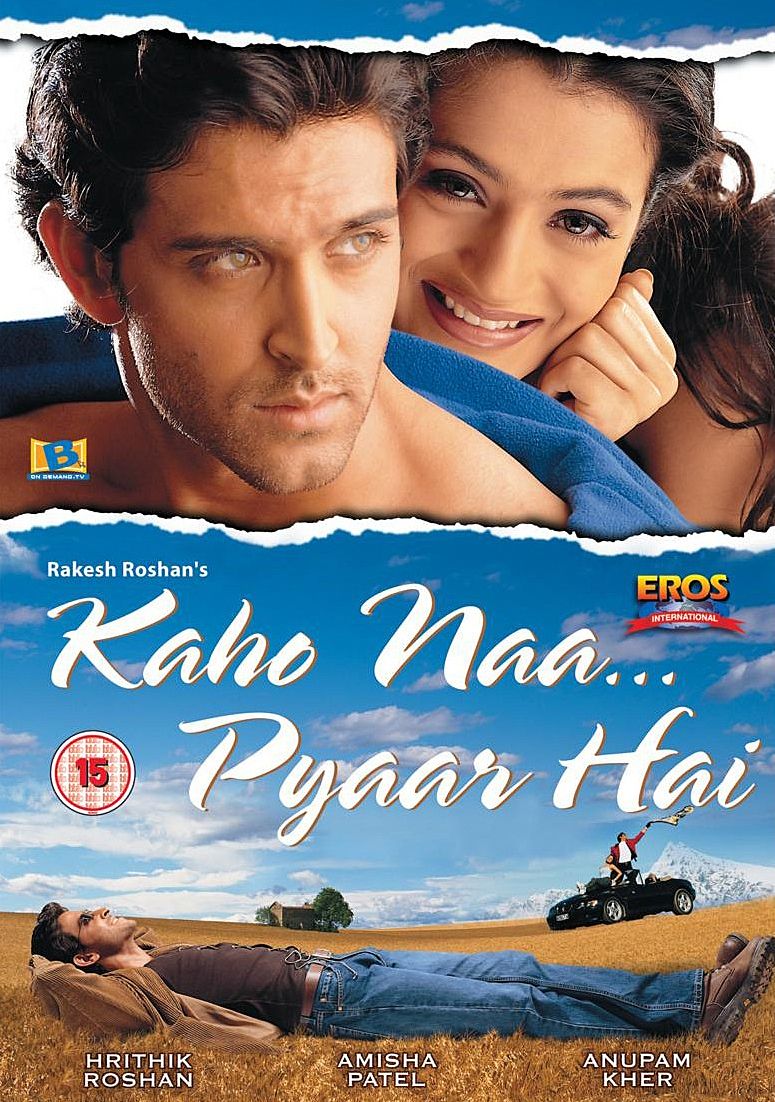

In the year 2000, as a nine-year-old boy, I was one of some 500 million people to see the blockbuster romance Kaho Naa … Pyaar Hai (‘Say … You Love Me’). The film was remarkable both for occasioning the debut of muscle-bound heartthrob Hrithik Roshan, and for being the first Indian production to use Aotearoa not just as a picturesque stand-in for Kashmir, but as part of the plot. With greedy-eyed shots of the Southern Alps, especially in the song and dance sequence ‘Na Tum Jano Na Hum’, New Zealand supplanted Switzerland as the freshest and most exotic location in Hindi cinema.

In her brilliant essay ‘A Stormy Affair’,[1] Auckland-based researcher Rebecca Kunin describes how Indian filmmakers became aware of Aotearoa as a location, how the country was strategically piggybacked into India on Roshan’s overnight fame, and the resulting increase in tourism – from 4,000 Indian visitors to New Zealand in 1997, to 17,000 in 2002. “Previous associations with New Zealand of prominent cricket players or mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary were replaced, at all levels of society,” Kunin writes, “with a new awareness of the beauty of New Zealand’s natural environment and its status as a fashionable holiday destination.”

It was during this time that my family decided to immigrate to New Zealand. Kaho Naa … Pyaar Hai became a talisman for my four-year-old brother and me. It was our only reference to the kind of life we were going to lead. My brother copied all of Roshan’s NSYNC-style dance moves (played out in the Wellington club scene), while I anticipated living in a manicured city full of alien citizen-extras.

My brother copied all of Roshan’s NSYNC-style dance moves, while I anticipated living in a manicured city full of alien citizen-extras.

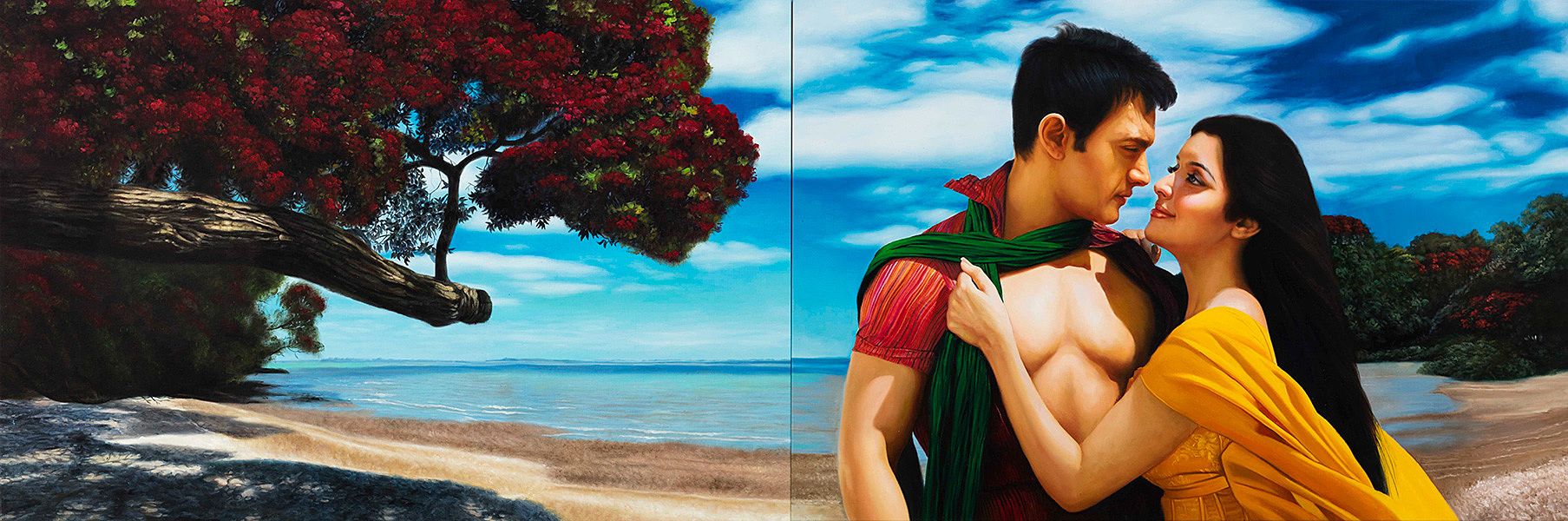

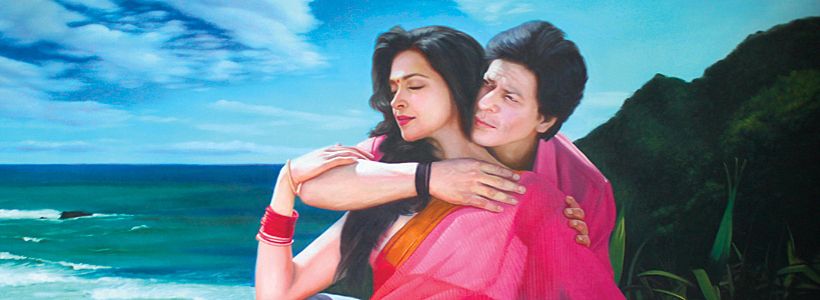

While I came to find out about New Zealand through Indian cinema, Bepen Bhana uses Bollywood to shape New Zealand’s perspectives of India and Indians. His recent exhibition, Frankie Goes to Bollywood at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, comprised a series of eight immersive, panoramic paintings, each portraying an alluring pair of Bollywood stars embracing in front of a spectacular West Auckland coastal scene. My favourite shows Deepika Padukone and Shahrukh Khan nestled in the flax bush above Māori Bay, Muriwai, in a pose possibly borrowed from the recent Chennai Express (2013). To be sure, the encounters are Bhana’s inventions. No Bollywood film features the flax bush, nor have the actors depicted frequented the Waitakere sites.

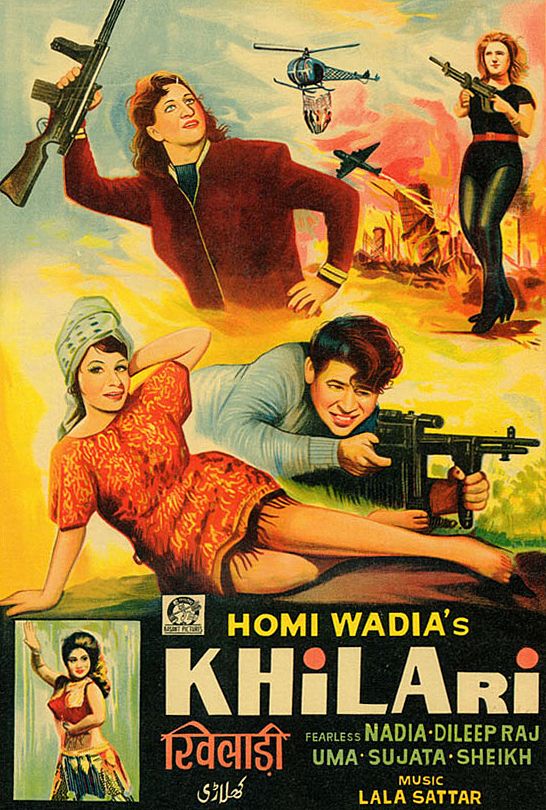

Bhana’s seductive, photorealistic works are reminiscent of billboard movie advertisements, and especially the paintings created by graphic-wallahs (sign writers) in India. Ubiquitous before the advent of digital printing, painted hoardings hooked in the audience with tantalising highlights from the pictures they promoted. The Wadia brothers, for example, didn’t need D. W. Griffith to tell them that all they needed to make a film was a girl and a gun. The poster for their 1968 release, Khilari, takes no chances. Three guns and four girls make the movie’s promise clear: a C-grade spectacle with violence, sexual titillation, and a thrilling encounter with the modern world.

Obviously, painted hoardings and their more recent printed counterparts are, in essence, commercial exercises. But their worth is not solely located in their effectiveness as advertisements. Such signs participate in the cluttered visual landscape of India, in which every inch of space is the site of a Darwinian struggle for survival. They’re found sandwiched between political slogans (cast your vote for the hammer and sickle), surrounded by public service messages (don’t waste water, you’ll need it later), defaced by government exhortations (pay your income tax and walk tall), and decorated with health regulations (get your child immunised). Sometimes, they’re lost altogether, obscured by competing advertisements. In amongst this kaleidoscopic clamour, the movie billboard becomes part of a wider dialogue between different users of images within a broader cultural context. It becomes a fertile ground for presenting, contesting and constructing new aspirations and identities.

If Bhana’s paintings are akin to billboard paintings/posters, then what is it that they present, contest and construct? It’s not every day that we happen upon Indian people in the New Zealand media, fewer still in pop culture spaces like television and cinema. I think of New Zealand’s Next Top Model judge Colin Mathura-Jeffree, the R&B singer Aaradhna, and the character Shanti Kumari (played by Nisha Madhan) on Shortland Street. The American representations are less flattering: the caricature Apu Nahasapeemapetilon from The Simpsons, or the socially incompetent astrophysicist Raj Koothrappali (Kunal Nayyar) from The Big Bang Theory.[2] Their success as characters relies on buffoonery and ineptitudes.

We could laud Bhana for adding to the visibility and positive representations of Indians in a Pākehā-controlled media, but should New Zealand’s Indian communities be waiting for the ‘mainstream’ to catch up? On whose terms should Indians be made visible? Bhana does not depict Indians succeeding in the Pākehā mainstream, but rather on their own terms. He titles his works in te reo Māori and Hindi, ignoring the ‘need’ for English as a mediating language. Members of the Indian diaspora see themselves reflected in their pop culture icons, and the New Zealand setting legitimates their connection with a new homeland.

On whose terms should Indians be made visible? Bhana does not depict Indians succeeding in the Pākehā mainstream, but rather on their own terms.

Most minority ethnic groups in Western countries seem tangled in a struggle for visibility and positive representation within a white-controlled establishment. #OscarsSoWhite, for example, went viral earlier this year when no African-American actors were nominated for an Academy Award. I remember feeling proud when A. R. Rahman won the 2009 Oscar for his score to Slumdog Millionaire – a movie Bhana detests. Rahman, a superstar composer in India, but relatively unknown in the West, suddenly ‘broke through’, big time, and was admired by the centre of power. While contemplating Bhana’s exhibition, I recalled my moment of pride and felt challenged. Bhana, I realised, would have insisted on celebrating Rahman’s success well before the Hollywood sheen. Bhana recognises the uneven playing field in which representation occurs, and shows in his paintings that Indians already set their own standards and ideals, and inspire their own audiences.

At this point, you may be concerned that we’re headed down a slippery slope towards separatism. After all, if migrant communities are so engaged with the media of an elsewhere land, does it not lead to their disengagement from the New Zealand public arena? In fact, the arena is already more plural than it might seem. Media outlets like Radio Tarana and HUMM FM, the Indian Weekender (‘pulse of the Kiwi Indian community’), Indian Newslink, and INDIANZ OUTLOOK all form part of the fabric of Aotearoa’s public dialogue. By creating these spaces, migrant communities are not disengaging from a mythical mainstream, but are instead making sense of their position on their own terms.

In my experience, the most prevalent attitude towards Bollywood from non-Indian New Zealanders is that it is either irrelevant, ridiculous, or both.

While Indian New Zealanders are generally enthusiastic about being involved with, and represented in, the ‘everyday’ news and entertainment industries, middle New Zealand tends not to show a corresponding interest in engaging with Indian media. In my experience, the most prevalent attitude towards Bollywood from non-Indian New Zealanders is that it is either irrelevant, ridiculous, or both: “heroes, heroines, and family feuds – so melodramatic”; “a silly song and dance every second scene”; “OMG – three hours long!” Even the term ‘Bollywood’ suggests an imitation, a rip-off, a taking from Hollywood. The fake version of the designer item, the parallel import, the simulation.

The title of Bhana’s exhibition riffs on the name of a 1980s band, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, asking us to consider what the difference is between going to Hollywood and going to Bollywood. There seems to be a centre and a periphery; Bollywood takes from Hollywood without inspiring reciprocity. Bhana uses the iconic actors of Hindi cinema to show a centre of power other than that of the familiar Euro-American film industry. With these paintings, the New Zealand non-Indian audience is required to assume the peripheral position to an Indian centre, to assume a passive role of observation and admiration. The film stars and the industry that brings them to New Zealand exert a soft power through allure and seduction, discreetly influencing our perceptions of India and Indian people.

The aspirational power each painting emanates invites us to review the stereotype of Indian people, not as awkward IT experts, meek dairy owners, or overqualified taxi drivers, but as self-possessed, strong-bodied, and beautiful people.

Main image: Bepen Bhana, Ko Amir rāua ko Asin i Otitori, Titirangi / Amir aur Asin Phrenc Khaaree par, 2016. Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

[1] Rebecca C. M. Kunin, ‘A Stormy Affair: An Analysis of Indian Film Production in New Zealand (1993–2003)’, in Sekhar Bandyopadhyay (ed.), India in New Zealand: Local Identities, Global Relations (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2010), 303–331.

[2] Incidentally, it is revealed in an episode of The Big Bang Theory that Raj tried to form a band called Frankie Goes to Bollywood as child, but that no one wanted to join, causing his parents to call on servants to be back-up dancers.