Interior Histories: Fragments Of A World At 40

Eloise Callister-Baker on NZ's pioneering photographers

Throughout time, those in power have constructed the reality that governs and constrains our actions and identities. At any given moment this reality looks like concrete walls and perfectly straight yellow lines on asphalt roads, but it only takes a few insistent voices to reveal how chaotic and bizarre it all really is, how much is predicated on unsupported but long-held assumptions, how much can change in years or months.

Take our adherence to a normative history of art in which men have been the artists and women, if granted access at all, are always prefixed with the “inferior” subclassification of female artists. Events in the 1970s marked a change to this - but more than forty years on those traditional paradigms are still writ large, and the story of that progress has buried in the pre-internet depths. Thankfully, strong people at home and across the globe continue to demand that the art world grows up and gains a mature sense of how the past informs the present. This year, my mother, Dr Sandy Callister, curated an exhibition of New Zealand women artists for the Adam Art Gallery in Wellington, contributing another voice to the chorus that creates this demand.

When writing about art it is often useful to establish a distance between yourself and your subject for the sake of criticality. When a close friend or a family member – let alone your own mother - is the artist, director or curator of a show there is a taboo when it comes to writing about it – it’s just best not to do it. But this time I didn’t have the patience to take a step back and wait on an in-depth piece by someone else that may never arrive. My belief in the artists in this show, and my desire to celebrate and protect what Sandy has achieved drives to me flip off that particular taboo along with anyone that may criticise putting my pride in my own mother before “do’s and don’t’s” of criticism (thanks Sandy for this confidence). This is an opportunity to further realise an aspect of art history that has insignificant documentation and attention, so that current practitioners can have new insight into those that paved the same path they walk.

Forming a lifelong friendship with Janet Bayly (an artist whose work features in Sandy’s show) when flatting together escalated Sandy’s interests in art photography and the histories of photography. Sandy’s devotion to photography led to her writing her PhD on the photographs taken by New Zealanders fighting as soldiers or working as medics, journalists and officials in WWI, which she eventually made into a book, The Face of War: New Zealand’s Great War Photography. Sandy has also been collecting art, especially art photography, and involved with various galleries throughout her life. But it was more recently, after she explored an exhibition of Joanna Margaret Paul’s photo and film work at Robert Heald’s gallery in Wellington, that she felt drawn to understanding further possible connections between Bayly and Paul’s works.

I grew up enchanted by the sombreness captured in Bayly’s polaroids of a frail pink dress caught in a breeze, which Sandy displayed in our home. Years later, she took me along to that Paul exhibition. In this way, Sandy’s interests influenced my own.

It quickly dawned on Sandy that Paul’s work, which has continued to gain traction throughout New Zealand and in London beyond her death in 2003, was “contemporaneous with Janet’s and equally unknown.” As she discussed this with curators and people involved with art, she began to realise there were many women artists in New Zealand who had experimented with photography and film right on the brink of its recognition as a form of art in the 1970s and 80s. Gradually, a list of artists and the works to be included in the show formed, and the necessity of the exhibition became clear.

Fragments of a World: Artists Working with Film and Photography 1973 - 1987 displays 30 rarely seen works – Sandy describes them as “intelligent” and “quiet” – by a handful of New Zealand women artists. Sandy deliberately left “women” out from the title: “You don’t keep saying it’s a male artists’ show, so why do we say women? I am resistant towards language that traps and constrains and makes it less accessible to a younger audience.” She also made it clear to me that she did not want the show to be pigeonholed as perpetuating gender as a binary but rather a show that features artists who “resisted categorisation” and deliberately played with the notions of performing identity and gender in their works.

Jennifer Higgie, the co-editor of the internationally renowned art magazine Frieze, often signs off her Instagram posts that profile barely known but incredible women artists with “Bow down”. Higgie also provides more general posts on women in history, such as a cave painting of a woman’s handprint, indicating that the first artists may have been women. New or old, Higgie’s imperative rings true - when women break down hierarchies and create powerful art, they deserve to be worshipped. And this highlighting of great women, disseminated globally through social media, is now becoming more common, particularly with younger people – the traditional gatekeepers aren’t as persuasive, if they read them at all. Fragments partly operates as a form of redress for artists who society failed to recognise – but, like Higgie’s Instagram, it’s also a celebration and recontextualisation of their works so they may speak to new generations.

It contains a selection of films and photographs by Janet Bayly, Minerva Betts, Rhondda Bosworth, Jane Campion (yes, the Oscar award-winning director), Alexis Hunter (world-renowned for the ways in which she incorporated feminist theory into her work), Paul and Popular Productions. The artists chosen for this exhibition all “demonstrate their embrace of and struggle with established conventions and hierarchies in the art, film and photographic worlds.” The tensions of the time in which they operated are well known, and many of the battlegrounds they documented remain unsettled now: economic and environmental crises, intersectional feminist movements, anti-war protests and African-American civil rights.

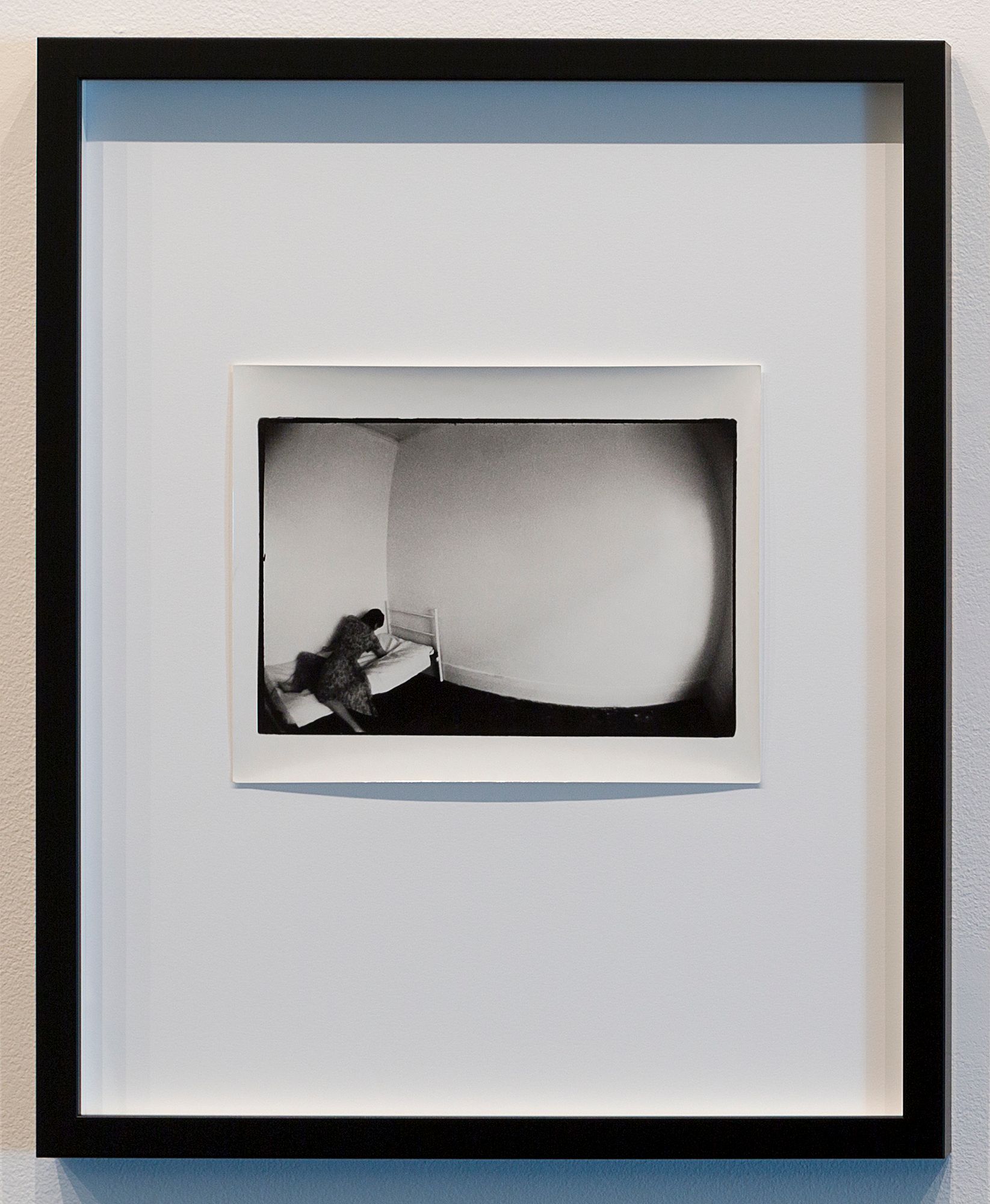

Even in the art world there was a tension between old orthodoxies and the new. How were schools and galleries to label photography: was it a serious art form? Or was the camera its own mechanical eye, constructed for documentation but little more? Forcing the issue, the brave women artists who Fragments commemorates wielded theirs cameras anyway, intending to make art whether there was a consensus on its legitimacy or not. Their experimentation and disregard for ‘correct’ technique – evident in the use of rough edges and test prints in Bosworth’s works and the physical manipulation of images with paint and a blade in Betts’ – was an attack on a status quo as decided by male deans, critics and dealers.

In 1975, The Active Eye exhibition at Manawatu Art Gallery became New Zealand’s first major survey of contemporary photography, symbolising a definite shift in this country toward recognising photography as art. The exhibition also recognised that women photographers were under-represented in this and other survey exhibitions and publications. The next year, the book Fragments of a World, which partly inspired the name of Sandy’s exhibition, featured the photographic works of 31 women artists, having initially received 200 entries following a nationwide advertising campaign for submissions. Of course women were making art – they always had been, here as anywhere – but what these publications and exhibitions realised is that they weren’t being seriously considered as artists.

This was, and continues to be, a worldwide issue. “Works in Progress”, a New York Times Style Magazine article that came out earlier this year, provided its readers with a list of women artists “we should have known about decades ago”. Unsurprisingly, many of the subjects were elderly by the time they finally received the recognition that their significant works had called for since conception. One artist featured in the article, Carmen Herrera, was 99 years old when she was interviewed. “There’s a saying that you wait for the bus and it will come,” Herrera told the interviewer. “I waited almost a hundred years!” Michelle Stuart, another of the featured artists, 82 and still in practice, claimed that she always had recognition “but being a woman, I’m not a big star somehow. You reach a certain point and there’s a glass ceiling.“ Each of the artists featured had lived a fantastic, colourful life; each has endured.

“I had been educated in an institution that taught that women’s art was inferior because of its subject matter. That enraged me.” Rhondda Bosworth stated at a panel discussion several days after Fragments of a World opened. “I never believed in this inferiority. Feminist writers have said the personal is political. It made me realise that I don’t have to worry that people may say my work is too personal, I don’t have to hire a plane to fly over the Andes to take a spectacular photo.” As Sandy explained to me, when the works featured in Fragments of a World were made they “didn’t fit into a nationalist narrative” unlike the well-known images from that time by artists like Laurence Aberhart and Ans Westra. Instead, these works are highly personal. On first impressions, they are complicated and difficult to categorise – yet their shared connections make the show a comprehensive account of the time and its lasting issues.

The works depict a performance and examination of self – often incorporating or questioning femininity – and emit the perspective of an inside world, although not in a sentimental or nostalgic sense. “They demand quite a lot of the viewer, you have to slow down and think what this work is about,” Sandy observes.

Many of the works also feel imbued with the sort of darkness that sometimes appears sinister or mournful, but tends to be inherent to most deeper explorations of the self. At a distance, the series of Paul’s photographs appear black with only pinpoints of light. On closer inspection, it seems like she hid with her camera in shadowed places while hunting down or becoming mesmerised by light – an illuminated washing line through a window, a streak of sun along a curtain. But this light is alien, and always at a distance. This use of low lighting is also employed by Bosworth and Bayly. In several of Bosworth’s works, a woman in black lies in various poses on a sterile white bed in the corner of a room – shadows creep towards her from the edges of the frame. In three blue-tinted photos by Bayly, she either faces a mirror or faces away from a mirror – her hair and small movements have blurred her face. There is an uneasiness to these images that comes from the way the subjects present themselves. The artists have given me permission to be a voyeur, but it’s a mixed blessing - the internal world they present to me is distorted, twisted.

Campion’s black and white short film, A Girl’s Own Story, operates in much the same way. It follows the occasionally interweaving stories of three school girls, Pam, Gloria and Stella, during the 1960s in Australia and depicts scenes of their adolescent experiences. The expected and the totally discomfiting sit side by side: an obsession with The Beatles and claustrophobic notions of suburban purity, but also parents who speak through their daughters in order to communicate with each other, incest between two siblings, and sexual discovery.

While the works in Fragments direct “our attention to the gaps and slippages in all histories of representation”, it is not fitting to describe them as solely historic, or a curated representation of another time – we do not see them through a film of dust. Indeed, Sandy claims that they aren’t even a part of this time continuum as we know it: “Situated outside our iconic image inventories, the works appear as fragments isolated from the continuum of time. The world they show does not feel like ‘seventies or ‘eighties that we have come to know through the lens of their peers...” This quality of being anachronistic by omission makes the show surprisingly fresh – something that can inspire viewers now despite the works being decades old.

Exhibition wall text highlights how the artists collated were among the first to experience with new media of the time. “These artists foreshadow how technologies now mediate our desires and inner thoughts; they are eloquent harbingers of our Instagram era.” And many of the images in Fragments do work at a phone-sized scale - Bayly’s SX-70 polaroids, Bosworth and Betts’ film images and Hunter’s images of a bloodied wall being axed down and a foot bleeding because of an uncomfortable silver high heel all reflect in some way the intimate stakes and/or subject matters of many Instagram feeds. The works are also a contrast to the maximalist (and often male) likes of Jeff Koons, Michael Parekowhai and Damien Hirst, who prefer to upsize rather than refine. In Sandy’s eyes, this type of “monumental, trophy signature work” is reaching its end.

In its place, these works speak to, predict and reflect how the internet generation capture and curate their own experiences. In the images that capture the artists’ faces and bodies are traces of the self-curiosity and performance that leads us to taking and editing selfies on our cellphones – the size, simplicity and instantaneity of which all aid in this exploration. Bayly once wrote about Polaroid that “the square SX-70 frame seemed potentised by its miniaturised scale” – now, the same can be said about the potential and intimacy given to us by our cellphones. At a discussion on the show, Bosworth confirmed her support for the possibilities of the cellphone selfie: “I love what’s happening with photography. Mass selfie taking validates my thoughts on what people really need.”

Meanwhile, the seriality of most of the works mirrors our modern desire to storify - to use multiple images to tell a story or reinforce a point. Bosworth says that the combination of photographing herself and displaying these images in series rather than one-offs was intended to create a fictionalised archive of the self. And if I delve into my own internet back pages - my archives of GIFs, photos I have taken, reblogs of things I like, this too is a partly fictionalised world. I have curated my own self within an edited, imagined milieu. Most likely, the Fragments artists weren’t using their art speculatively, to predict how information online would be presented to and consumed by us - but their correlation to these processes seems eerily relevant.

As goes Wellington, so does the world. “Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers?”, challenges an exhibition now showing at the Museé d’Orsay in Paris. The show’s foundations rest on new research that has reassessed women’s “extraordinary contribution to the growth of the medium.” It aims to show “how women embraced the photographic medium as part of an artistic and professional empowerment strategy, and conquered territories which were previously the preserve of men.” Although women have had this involvement with photography since its invention in 1839, the show and its accompanying publication are, surprisingly, the first of their kind in France.

Like Fragments of a World, the French show offers thrilling and necessary reassessments of history, though they may only be effective to a point. These exhibitions are creating sparks throughout the world, but sparks don’t start a fire – they get rained on, stagnate in the damp and eventually fizzle out. What Sandy sees as the necessary ignition for this fire – what she hopes for along with the many who have embarked on similar projects – is that this evidence of women artists who have created work in the past can bring confidence to a younger generation. This generation of artists, like those involved with North Projects, Enjoy, Fresh ‘n’ Fruity, Blue Oyster Art Project Space and many other project spaces, were already going from strength to strength before these shows, and cater for diversity that Fragments of a World cannot as a product of its time. But to have a sense that we are not alone in our vision is empowering. Take this opportunity to re-examine.

Fragments of a World will travel to the Michael Lett gallery in Auckland next year. It will also be made into a small publication.

Cover image: Janet Bayly, Self Portrait /Blue Face (detail), 1979/2002, four colour Lambda prints from SX-70 Polaroids. Courtesy of the artist in Fragments of a World, curated by Sandy Callister, Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi, Victoria University of Wellington (photo: Shaun Waugh)