Four Pacific Female Painters: A Review of This is a library

An exhibition that features four female Pacific painters is a rare thrill, writes Ioana Gordon-Smith.

I only came to know of Teuane Tibbo when her work was included in the 2013 Auckland Art Gallery group exhibition Home AKL. Tibbo (1895–1984), a Sāmoan-born and later Auckland-based painter, is often noted for the fact that she began painting aged 71, in the mid-1960s, without any formal training. Her work quickly gained the attention of galleries and artists alike. She became the first Sāmoan to hold a solo show at a dealer gallery (a distinction that, as many commentators have noted, reveals more about the Pākehā dealer system than anything else) and was well regarded by prominent New Zealand painters, including Pat Hanly, Michael Illingworth and Tony Fomison. Despite being a highly favoured artist, with work acquired by most major New Zealand museums, Teuane Tibbo isn’t a household name.

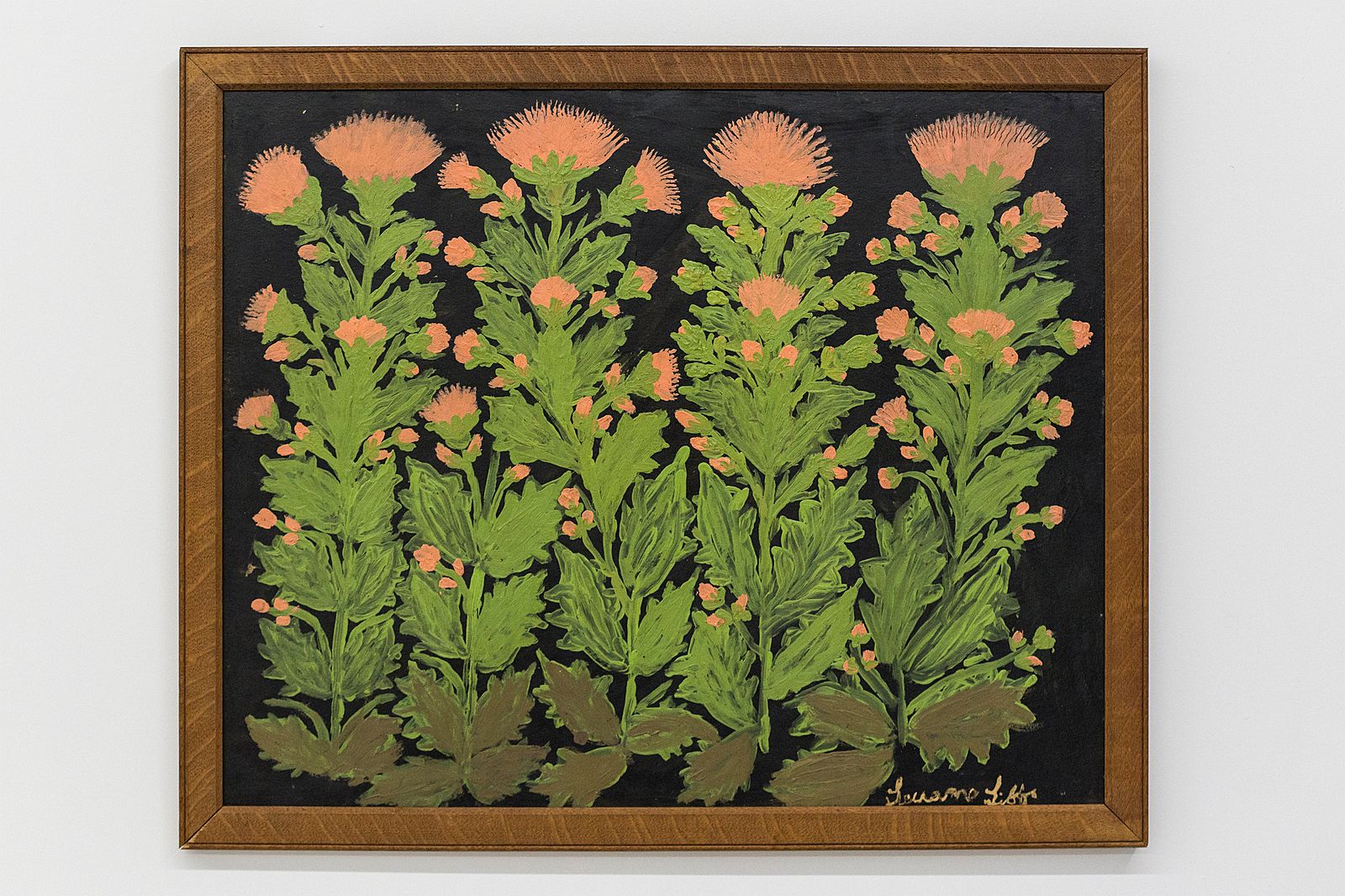

This is a library, curated by Hanahiva Rose, places the work of Teuane Tibbo alongside three contemporary female Moana painters: Claudia Jowitt, Christina Pataialii and Salome Tanuvasa. This is the first time I’ve seen Tibbo’s work since Home AKL. Rose’s selection is pleasingly generous, including six of Tibbo’s paintings. Tibbo’s floral works are a particular pleasure to view in person. In Poppies II, floating bouquets of flowers lean towards the centre on a backdrop of electric sky blue. Opium Poppies is a particularly stand-out work; thickly dabbed petals in bright corals and pinks against cool greens and blues.

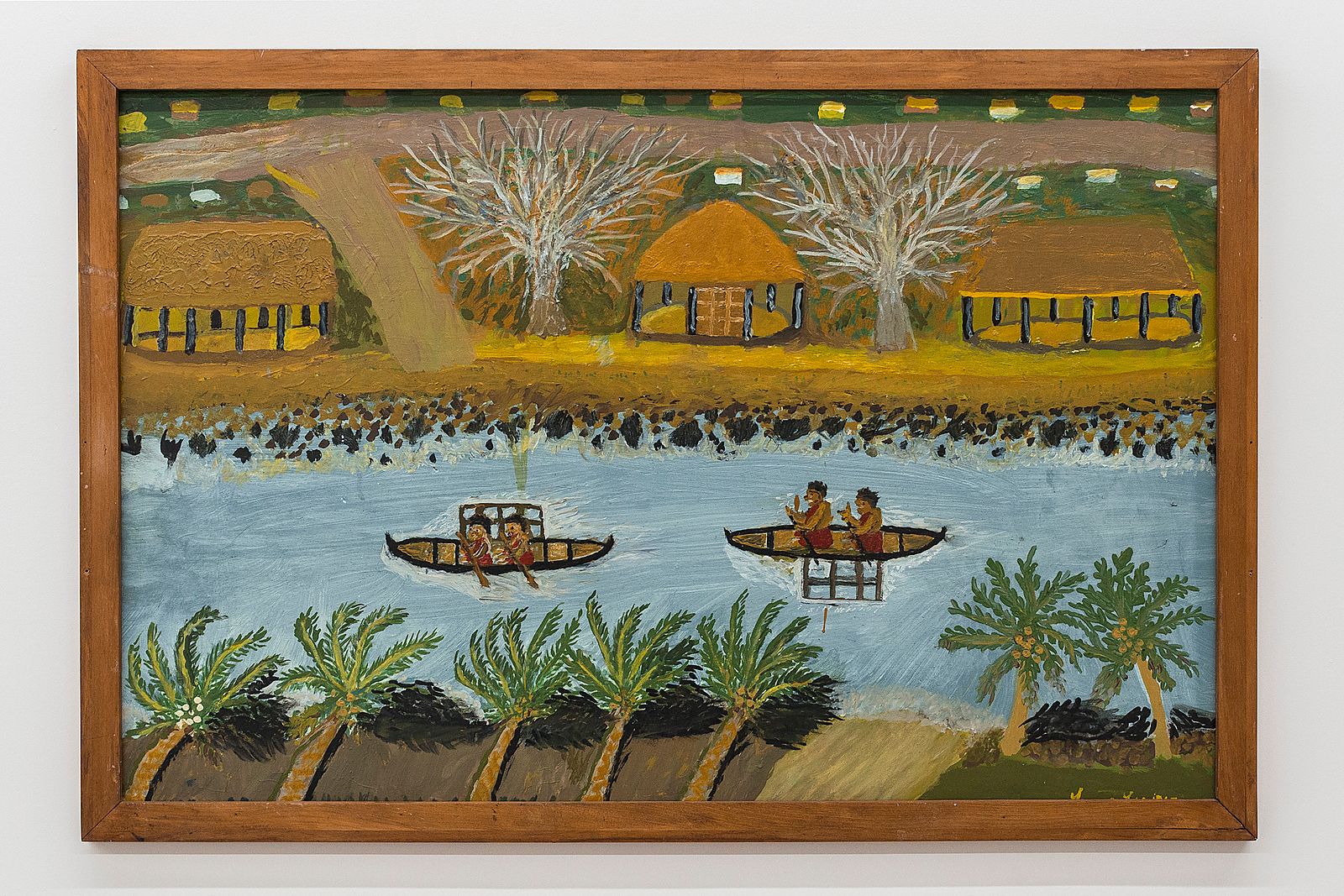

In Enjoy’s back gallery are Tibbo’s works depicting Sāmoan scenes. These compositions are denser, busier, filled with rows of canoes, fale, people, coconut trees and implied action. Like the floral works, forms are made with an economy of brush strokes; people painted without hands or feet and just dots for eyes. The works also distinctively combine multiple points of perspective. In Untitled, 1967, for example, the shift from a high perspective to a frontal perspective makes some supposedly upright trees look like they’ve been flattened by gusts of wind.

At the simplest level, This is a library is notable simply for presenting so many of Tibbo’s works at once. But the exhibition text also suggests connections or influences between Pacific art history and contemporary Pacific practice. The show features a range of types of connections, some direct. Five of Salome Tanuvasa’s paintings and two of Claudia Jowitt’s works, for example, have been made either in direct proximity to Tibbo’s works or specifically for the show.

Other connections lean towards the thematic or formal threads. The media release notes that “Tibbo’s work can be seen to foreshadow consistent themes in a new generation of artists: memory, place and the idea of home”. They’re broad themes that could draw together many a selection of diaspora artists, but, for sure, site and place are consistently echoed across each of the selected artists’ practices. By far the most interesting connection, though, between Rose’s selection of four painters is a particular disregard for painting genres, and the consequent spread of figuration through to abstraction and approaches to materiality.

Salome Tanuvasa’s works, with her now distinctive approach to squiggly marks, hum with a sense of being made in immediacy to context. Tanuvasa works with a range of signs: loops, squiggles, globular forms, streams, rows of angular and curved marks that mimic lines of handwriting. Some visual influences might be guessed at – Tanuvasa’s suite of three smaller works echo the greens, blues, pinks and corals from Tibbo’s Flowers II, for instance – others might be missed. Perhaps the most surprising feature of Tanuvasa’s works is not her marks, but her treatment of the canvas. Each work has had its corners cut so that the edges fold up, creating an in-built frame. Resembling something like flattened cardboard lids, the lifted edges/frames suggest both a self-reflexiveness and self-sufficiency.

Christina Pataialii’s paired paintings, Nana (2018) and Boy’s too young to be singing the blues (2018), are both portraits of the artist’s grandmother, the titles hinting at intergenerational concern. Across both works, large, gestural swathes of paint flit between the figurative and the abstract. Implied forms – a sharp, angular neck, shoulders and torso, or a softer, shadowed vase – sit alongside, under and over various marks overlaid and erased over fields of colour. The push/pull between composition and gestural marks is made more cacophonous by the mix of materials – acrylic, charcoal, house paints and patches of untouched drop cloth.

Claudia Jowitt’s most recent works, which use shells almost like a canvas or frame, are particularly stunning. Strings of paint beads criss-cross in dense layers over the shell’s cavity like latticework. The dense patterning of small orbs, made up variously of acrylic as well as coloured freshwater pearls, silver leaf, masi and vau, resembles something like a coral reef, or at least the sense of an ocean home. The show nicely includes a range of Jowitt’s work across media, from the more sculptural works through to framed watercolours. Together, they give a sense of an artist testing out how materials, application methods and patterns derived from female and Pacific contexts might extend outwards in multiple directions.

While the exhibition text suggests various types of connections, thematic and formal, it’s hard to tell which ones express and deliberate, and which are simply broad strokes. There’s clearly some background context too, which could only ever be partially known. One of Tibbo’s works in the exhibition, for instance, comes from Claudia Jowitt’s private collection, another from the Jowitt family collection. A lovely text by Jowitt in Femisphere outlining her discovery of Tibbo’s work further suggests a level of dialogue or influence that exists outside of the public eye.

It’s uncommon to be able to view this much painting by female Moana artists

That said, I’m not sure the exhibition was ever intended to make any grand claims, content rather to simply allow varying threads to be made, regardless of the intention. In fact, what’s most thrilling walking through the show is the distinctiveness and strength of all four painters. It’s uncommon to be able to view this much painting together, or at least this much painting by female artists, or this much painting by Moana artists, and certainly not this much painting by female Moana artists. Let’s not underestimate how rare that is. Looking back at group shows of Pacific and Māori painters, I can really only think of Pacific Materiality, curated by Natasha Matila-Smith, or Ngahiraka Mason’s Five Māori Painters.

In both the exhibition’s intent and its title, I’m reminded of the similarities between libraries and exhibitions. Following the proposed closure of Auckland University’s specialist libraries, a number of commentators noted that the problem with not having a physical space isn’t simply access, it is the elimination of the chance find. Similarly, exhibitions work most successfully by removing the need for a Google search and placing work directly in front of you.

In thinking about what we know of Moana painting, current and past, exhibitions persist as our primary encounter. In presenting these four artists together, This is a library reiterates the importance of a physical space that allows for leisurely perusal across works – the chance encounter, connections made between painters – and unfortunately how notable it is that, in 2020, we’re still trying to build the database.

This is a library

Enjoy Contemporary Art Space

13 Mar – 18 Apr 2020

Feature image top of page:

Claudia Jowitt, Vasua (for Teuane), 2020

All images courtesy of Cheska Brown