The Dignity of the Whanganui: A review of Flow by Airini Beautrais

Elizabeth Morton reviews Flow: Whanganui River Poems by Airini Beautrais and falls in love with the Whanganui river as well as Beautrais' poetry.

Elizabeth Morton reviews Flow: Whanganui River Poems by Airini Beautrais and falls in love with the Whanganui river as well as Beautrais' poetry.

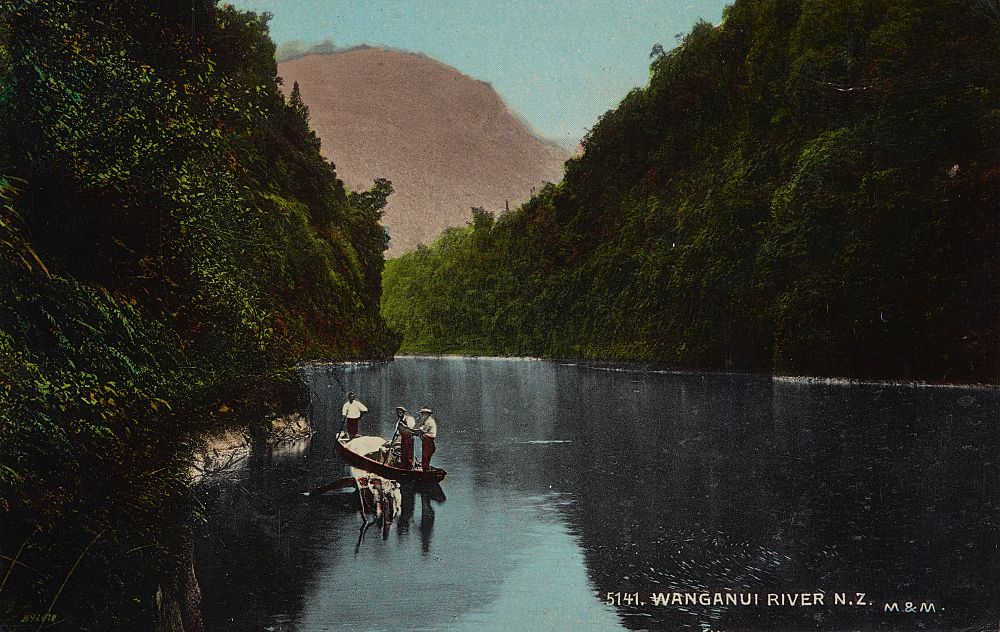

Here’s a riddle, of sorts. What is 290 kilometres in length, drinks from Mount Tongariro, and is a legal person?

Airini Beautrais’ Flow captures the personhood of Whanganui River, exhumes its legacy and the people who have loved and fought by its waters. As of 2017, Whanganui River was granted the status of legal person, as part of the Whanganui River Claims Settlement. This is a person steeped in history with the usual skeletons in familial closets; with spats and episodes of ugliness and loveliness. It is a macro-being, a dissipative system, of membrane and parts.

I don’t know the Whanganui all that well. It’s not the river of my childhood and it doesn’t feature in the architecture of my life. I had a garden creek, at best, with eels, and petrol rainbows, and neighbourhood dogs that gobbled its ducklings. It was no more than a trickle.

I’m writing this on an airplane, guilty of sullying the planet with a wake of carbon emissions and plastic pottles of unseasonal vegetables. I am returning from a river journey. My father and I were chasing the River Wye in a little Kia Corsa, crossing back and forth over it, walking amongst the riverbank wildflowers and dumped outdoor furniture. It is not my river either, but the chase was rich in its variations, and with each bend came a new set of people, a new feeling of holiness or the mundane. All the while I thought about Beautrais’ poems; how peopled they are, and how political.

Beautrais writes the biography of a river that is fouled by dairy farming, urban waste, and deforestation. The health of New Zealand waterways is a hot topic just now, and Beautrais tackles it with delicacy, introducing us to characters who speak of the ‘good old days’ without giving us a stern talking to or a waggling of the finger.

Travel has a way of messing with your circadian rhythm. On this airplane I’m not sure whether to sleep, watch a trashy movie, or whether to jog around the fuselage aisle. Hours bleed into hours. Time dilates. I’m somewhere over Bagdad.

The health of New Zealand waterways is a hot topic just now, and Beautrais tackles it with delicacy.

I have Flow spread on my fold-out tray. Beautrais’ poems flirt with time travel, and are non-linear, with eddies and tributaries, arranged as a mash up in three sections: ‘I Catchment,’ ‘II A body of water,’ ‘III The moving sand.’ The river is a manifestation of time. A line from Borges comes to mind: ‘Time is a river which carries me along, but I am the river.’ The temporal does not exist in the absence of conscious events. And the river is inseparable from its inhabitants. The river is where histories converge. Colonial and pre-colonial (‘No Pākehā. No surveys’), deciduous and native, flora, fauna, and ‘disposable nappies.’ The river has stories to relate, and, as Beautrais writes, ‘The greatest stories of all time are geological.’

In the first section of Beautrais’ collection, poems are located and date-tagged. She offers a map, so one can follow the river around. There’s ‘Orākau, 1864’ and ‘Manunui, 1928,’ for instance, paddling back and forth to ‘Taumarunui 2014.’ Having no geographical bearings whatsoever, these tags were an orientating force.

The poems themselves are atmospheric and expository. The first commences with rich depiction of a point in Taumarunui where the Ongarue and Whanganui rivers converge:

Two rivers meet, at an acute angle,

hold a point of ground in their fork.

Although this place is called Cherry Grove,

there are only a few cherries,

and not the edible type. Looking down Whanganui,

one bank grows willows and Japanese walnuts;

the other, corn and half a tōtara, unbranched

by the wind. It’s the end of a dry summer

The poem that follows takes us into a realm where every entity along the riverside has an élan vital, a sort of elementary life force. The landscape is witness to the blood-spilling of men at war. Orchard tree, palisade and hill all communicate with the reader. The field speaks:

The soldiers dug their ugly sap,

then swarmed into its earthen gap.

The cannons groaned, the fuses took,

With every booming shell, I shook.

Ahead lie verses that grapple with dark themes – there’s the 1916 Kākahi murder-suicide, the New Zealand land wars, floods, and falling branches. But these are related dispassionately, and counterweighed with moments of reprieve. At one point Beautrais overhears a conversation about ‘the three Ps of the Treaty of Waitangi,’ with the speaker offering ‘people, peace and … pineapples.’ This comic moment transforms into something profound, as Beautrais ponders conversational intervention and the sense she ‘shouldn’t be here.’

There is a hint, here, that the writer is uncertain where the boundaries of what she can talk about lie. She is careful. And she is an assiduous researcher. In an interview with Victoria University Press, Beautrais tells, ‘I felt a responsibility not to bend the facts when it came to Māori. Those aren’t my stories to fabricate.’ There is no poverty of Māori narrative, though, and Beautrais lets it take the front seat in her river story.

Beautrais’ work is abuzz with occupation. There are fishermen, bushmen, rail workers, woodchoppers, farmers and road workers. But this is more than a catalogue of crafts. Nature can stand on its own two feet. There are some wonderful images, like:

Sunrise lights the valley’s pipe,

spits polish on the camera lens

or:

The first snow falls

like sugar, sown

breath-thin

on each blank mountain’s face

Beautrais’ Flow is an ambitious enterprise with breadth of scope, and assortment of form. Beautrais proves she is no one-trick pony. She does sonnets and quatrains, and pieces that delight in wordplay and alliteration:

The chain clanking,

the clouds closing

we waded through wetness. Waste is the word for it.

Feeling each footfall, scenting the foetid

slurry of shrubbery sliced with the slasher.

The fog had a freshness I felt through the flannel

cloth of my shirt: it clung to me, clammy

Rivers are the bellwethers of the health of our environments. On the final day of chasing the River Wye, we met a fisherman at breakfast. ‘There are salmon and trout in the River Wye,’ he said through a mouthful of brined lox and egg. ‘It’s coming back to life.’ Later, my father and I leant over a bridge in Glasbury, watching dragonflies zip above the water, and cows supping from the riverbank, oblivious to any conservational blot.

I have fallen in love with the Whanganui River from afar.

In Flow, Beautrais tiptoes in the deep end of things. She has an envious nimbleness of touch. She sees the dignity of the Whanganui, which is the dignity of personhood. As we head towards the mouth of the river, in no particular chronology, we register the sea:

And each wave curling in to the shore

is like the sea saying what are you waiting for?

Flow is a movement of water, a pulsing of blood vessels, a passage of time. With Beautrais’ collection, every poem feels necessarily placed, perfectly considered, and yet surprising. This is a work that demonstrates the potency of this poet, her range, and her ability to use language to take the reader dancing. If the river is bellwether of environmental health, the poem is the gauge of the condition of culture, and, of this, I am encouraged.

I have fallen in love with the Whanganui River from afar. From this airplane I resolve that my next river episode will be a local one.

Oh, and as to Beautrais’ audacious title, I can assure you, this poetry flows.

Flow: Whanganui River Poems is available from Victoria University Press.