Fire

Justine Jungersen-Smith on parenthood and anxiety.

I have two children. Every day I am their mother. My anxiety, and my devotion, never leave. They have made themselves comfortable in my body.

*

Look, there. A house is on fire. See the green slope of the hill? See the long low row of flats? There's a street light in the smoke. The fire is so close to where I am standing, at the window of my own house, my small child looking out too.

*

My mother used to dream that her unborn child was a lizard. She had taken some antihistamines early in her pregnancy and she felt sure, late at night, that they had affected her somehow, that she would give birth to something strange, a reptile baby As a child I didn't like this story, of course. But now that I've had children of my own it seems a very reasonable surmise. I can see her very clearly: lying in bed in the dark, feeling a lizard darting around inside her body.

*

There's an image I hold on to, I guess it is more of a scene, or even a memory, given I can feel it in my body as if I have actually lived it. I am submerged in deep water, and I swim down and down and under, like a dolphin swims I guess, although that is perhaps too joyous a simile for something that appears involuntarily in my mind in moments of stress, small and large. It is an attempt to outrun something I don't want to think about, to sink down, to swim under the thing, to escape it by putting a great weight of water above me.

*

It is dark, and we are sitting across a table from each other and my friend, holding her cigarette far away from her body so her clothes won't stink when she goes home to her babies, leans in close and says: when I was pregnant I would would walk on the far side of the footpath in case a car came up over the curb to kill me and my baby. And there is the car, roaring into my mind from stage left, revving its engines, waiting to pounce. It's very shiny, all hard metal and velocity. And now that I have seen this car once it will reappear without me asking it to. Anxiety comes, so often, in the form of repeated visions.

What are the thoughts you must run away from? I ask my friends, parents of young children for the most part, kind people who don't mind me sifting around inside their secret selves for a while. And they say: tsunamis. Earthquakes. Balconies. Driveways. Any body of water large or small. Imagining a baby falling out of a window, again and again. Imagining Melancholia's asteroid appearing above the curve of the earth, every night, for the whole first year of a baby's life.

My friend keeps a seat-belt cutter in the car in case it somehow becomes submerged, small bodies trapped inside. Another friend used to walk through crowds holding her pregnant stomach in case someone punched it. At night she would not be able to sleep, her mind so busy imagining worse. And once I hear all these stories I feel as if I can see them, so many people, suddenly stopping at the beach, breath quickening, or stuck in the throat as they say, even though the ocean is calm and flat, even though it is such a perfect day. So many people shaking their heads, quickly, sharply, trying to get the thought out; the thought holding on, stuck like a cat's claw, stuck in a soft part of the body until the children are rounded up, dusted off, taken home to warm beds.

My own vision is dystopian. The earth is getting hotter, after all. When I least except it, when I am cleaning the kitchen, or walking to pick up my kids, I imagine a parched world, artificial intelligence running free, our babies living on, somehow. And then I imagine diving, swimming down under deep water, away from all these thoughts.

Heat

The baby has a fever. Her arms are flung out on either side of her naked body (ribs), just a nappy (is it wet is it wet?). Short rapid shallow breaths all night, her hand reaching out to check I'm still there, still lying next to her. And I'm there, of course I am. And I feel as if I have a fever too, for I feel her fever in my own body.

*

When my first child was four I went to Berlin for a weekend. It was the first time I had ever been away from my little boy. We were living then in a small city in Germany, two hours from Berlin one way, two hours from Prague the other. I had left our apartment, caught the tram to the train station, found my seat on the train to Berlin, all with my heart in my mouth, as people say, but, truly, it felt just as if my mouth, my face, was so filled with heart that I couldn't get any air in or out. But as the train picked up speed (windmills out the window blurring faster and faster) I felt I could actually feel the edges of my body begin to firm up, to close in: there is no one else here but me, my body said. Just me. And in that moment I saw how clearly my self had changed since having a child. My body, my cells, were no longer my own, and I didn't know what to do with that vision.

When my husband's mother was dying she lay in her bed in the hospice and worried about my brother-in-law, her youngest child, her baby, hitting his head on the edge of the bed. She would wave a hand out, made floaty with morphine, the hand hovering in the air near the sharp metal of the bed, covering the edge so a little toddler head would not smash into it, blood in soft baby hair, a lump like an egg. In reality, the toddler was nineteen, sitting in the hospice lounge rocking madly on a mustard-coloured rocking chair, way too much speed bouncing in his body for the situation he now found himself in.

All over the world there are old women walking up corridors with baby dolls in their arms. Their minds have gone somewhere else, floating somewhere above their bodies, busy in ways we don't understand (the past glowing all around them). And there they are, these old women, rocking dolls in their arms: hush little one, go to sleep. If I keep walking the baby will stay asleep.

*

This way, says the baby if I try to roll on to my other side, with my back to her little body. I must lie curled right around her, small feet resting on my thighs, soft head under my chin. Stroke stroke goes her small hot hand (on my cool arm, on my own cheek), as the night gets darker and then lighter. As the sun begins to wake up the baby finally rolls away from me and falls asleep.

Fear has many eyes

It's not hard to see the air actually trembling around new parents. It looks like static sounds. If I had to draw it I would make it look like a haze of small coloured balls buzzing around their heads, pushing against their skin, getting in their eyes. It's so much easier to let the worry in when one is sleep deprived. There it is, on a loop: finger-painting, protein, enough fresh air? Not enough greens, too much TV, tetanus lurking somewhere, in the house (rusty nails), in the garden (rose thorns, it's true). All the big and the small fears mixed up together, scale no longer relevant, every single one felt.

What is the source of this fear? Where does it begin, two sticks rubbing together? Zygmunt Bauman has written about the existential tremors running through these present times: inequality, injustice, uncertainty creating an experience of what he calls liquid fear.1 Those two words next to each other are very good, I think, not least because fear does feel like such a liquid thing in the body, slipping up and down under the skin, running in circles around the heart. Bauman describes liquid fear as diffuse, scattered, shape-shifting: fear of unemployment or homelessness, fear of drought, floods, earthquakes, fear of assaults, pollution, terrorism, financial meltdown. Fear of unhappiness. Fear of, of course, being afraid.2

It certainly seems, to me, as if we are all trying very hard to outrun fear, while simultaneously trying to balance (arms outstretched) on the line between feeling too much that it hurts and feeling enough to still be able to dance, baby. And sometimes I wonder if it is less about living in these present times than it is simply a condition of being alive. Perhaps it's just that we are all getting older? Is this what aging feels like? Being unable to swim under the fear anymore? Imagining our own brittle bones, little fluttering bird hearts giving up the ghost at the slightest BOO.

Everything is so untidy

We are in a traffic jam. We sit, not moving, for an hour, car after car. The children are terribly restless. Why are we stopped? they say. Why? Why? And, well, what to tell the children? Because a motorcycle has crashed into a truck in the tunnel? Because that small space (so small and narrow it is enough to make one want to dig in the earth just driving through it) is filled with blood and guts? Bodies and metal are inseparable (machinery will be required). People are lying dead, and we cannot just drive over dead people. That's why we are not moving.

*

I am in my front yard having a fag with a new friend while our babies run around shrieking inside, up too late (doom ahead). The new friend leans back against the fence. She blows the smoke from her cigarette straight up into the night air, and she says: my friendships are better now that I have had children.

Yes.

What is it? Life and death. Bodies. Desperation.

Do you remember a baby crying (not your own) and your milk coming down? A child's grazed knee feeling like it was your very own? You had to try so hard not to look down at your own knee to check for the injury, so huge was the empathy, so thin was your own skin.

I used to imagine myself on a long-haul flight, strapped into my seat, reading a book. No one could ask me for anything. No one could ring me. The flight would go on, and on, and there I would sit, needing nothing but to remain sitting there, alone. It's a normal enough fantasy for a parent of small children, I think, and other parents have told me similar, this desperation to be alone, to be where they don't have to look after anyone for just one moment. Presumably this is the fantasy of most people who look after anyone requiring constant, compassionate, all-consuming levels of hands-on care. This wanting to run somewhere, back to somewhere (being young shining somewhere behind you? Drinking and dancing, the sun coming up, sleeping all day). Someplace where they might find themselves again, where they might find the edges of themselves in tact, the edges no longer so soft and blurry from so much empathy.

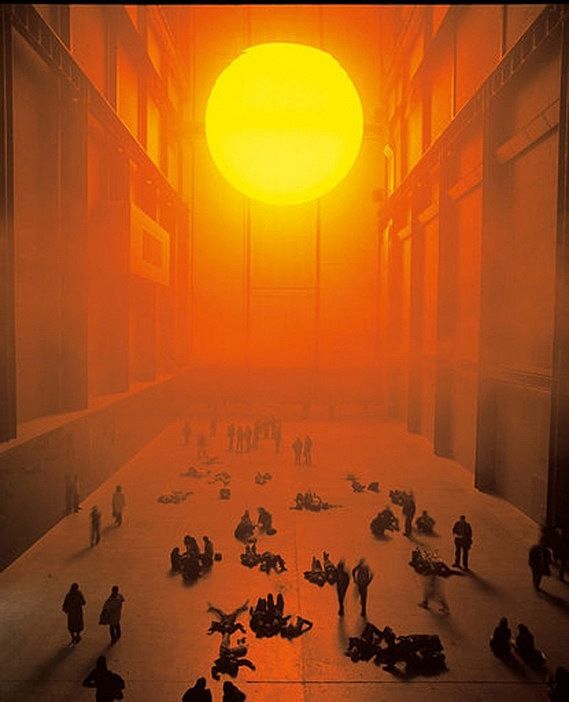

"Olafur Eliasson, The Weather Project, 2003. Installation view, Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. Photo: Tate Photography © Olafur Eliasson"

It really helps, I think, to have unholy habits. Once you have wiped down the bench so well that it glows, the very air sparkling above it, then you can go outside, you can go outside and smoke secret cigerettes in the dark where no one can see you.

I have never not felt the crying of my babies in my body.

It is enough to make one lose one's mind.

These fragile bodies, these collapsible selves.

The ability to feel into

I couldn't watch Game of Thrones when my children were small, my friends tell me. Or Breaking Bad. Or True Detective. There's no joy there, none at all. Yes. It's hard to watch or read certain things when there are small children sleeping somewhere close by. Hardest when they are very young, with little tiny fists, long eyelashes on soft cheeks, legs still bowed from being curled up so tightly inside another body. So many laptops shut, books closed, films walked out of. Loud humming. Heads turned, sharply, to shake the image out of our minds before it lodges there. Eyes firmly closed. Fuck that shit. Too much heartache. Too much sexual violence. No. Here we all are, eyes closed and angry, all of us willing a safe and kind world into being for our children to grow up in.

*

In The Art of Cruelty Maggie Nelson quotes Lionel Trilling: “It is possible that the contemplation of cruelty will not make us humane but cruel; that the reiteration of the badness of our spiritual condition will make us consent to it”.3 And certainly that's how it feels, sometimes. I actually thought, watching a boxed set of E.R. (of all things) while I breastfed my newborn, that all the blood I was watching was making my milk sour. A mad thought, perhaps, but it felt real enough at the time.

The world is on fire

When I first started thinking about anxiety, and parenting, and how these things looked next to each other, I thought it was just about bodies. Anxiety running in the blood, which could be ameliorated with the right drugs, or exercise, or nicotine, or recycling more, or simply being around kindness. But this feeling, of too-thin skin, the feeling that empathy had become another sense, appearing involuntarily like taste or smell, of being at the mercy of such big feelings, and all the time, began to seem relevant to not just my body, but to the whole world. When I looked around me it began to seem as if the whole world was feeling these big feelings, everyone sunk down deep in a trembling crisis.

There it all is, in Horace and Pete, that sustained scream calling itself a sitcom: life and death and rage for the taking. Even the latest series of Girls seems somehow nostalgic, a new heaviness settling down upon it. Emily Nussbaum has argued in The New Yorker that “in a post-Louie world…all the best sitcoms deal in melancholy and rage”.4 And fear, I would add: every episode of The Leftovers trembles with existential fear. And, even though my body doesn't much like it, I open my eyes wide for these melancholic entertainments. For they make me feel as if the whole world has a little baby, as if everyone is running around with skin too-thin, as if we are all holding hands (so tightly) while we look around us at the world we have found ourselves in. Perhaps ZygmuntBauman is right. Perhaps we are living in a time when it really does feel like the future is slipping through our fingers.

Perfection

When I think about the future I put the music on, loud. There's nothing like dancing with a giddy toddler in your arms. It's enough to get through the day.

*

A warm little hand in yours while you wait to cross the road.

Such soft baby skin.

*

We all have to sleep at night. That's part of being a parent. When they are small it goes like this: shhh little one, shhhhh (pat on the bum like a drum). And, when they are a bit older, it goes like this: lie down close, feet touching under the blankets. Shhhh, here is something your grandparents told me when I was little. I had terrible growing pains. My arms and legs ached all night. They said to me, so softly: imagine a rose inside your body, inside your heart. Not the stem of a rose, who wants thorns in your heart? No. Just the flower part. Very pink petals, dark pink in the centre, lighter pink moving to very light pink on the outside. Can you see it? The rose is glowing. It's glowing so pink and warm. And the glow is growing, it's getting bigger and bigger and it is beginning to spread out from your heart and into your chest. Don't think about ribs and muscle! Think about your body as a vessel, not substance. It's just for holding the glow. The glow is so warm. It's spreading to your legs and your arms. It's making your fingertips and toes tingle. It's filling up your face and pushing up against the very top your head. Your whole body is warm and pink and glowing and it makes you feel so happy and because you feel so happy and warm you can go to sleep.

And you do.

*

My little daughter wakes me every morning with the small squeak of a baby animal. She pushes her nose into mine, rubbing our animal noses together, and she can tell by the amount of enthusiasm I have for this game what the day will bring. Don't be so tired mumma, she thinks, this very small child. She pushes her face in so close and fills it all up with a smile and whispers let's get up mumma. And so each day begins. This small warm baby animal refuses socks, her warm feet becoming colder, skipping across the floor on feet of ice, her brother the same: why will you children never wear clothes?

*

Some days it helps to imagine you are in a music video. If you shake your body in a move most often your children will shake their bodies too.

Some days it helps to listen to chord changes with the right emotional weight, on repeat (head up close to a speaker the better to feel the music in your body). On those days, if you let the music right in, then it will be all you can do to stay in your seat and not leap into the air with all the pure motherfucking joy of being alive, on this planet, at this very moment.

*

Here is a mother, walking up five flights of stairs with headphones on, Missy Elliott on too loud, the music smashing into her eardrums. When she gets to the top she will feel a laugh beginning in her chest, it will bounce around inside of her for a moment, and then the laughter will leave her body and make its way out into the world.

Biology

My husband's mother was a physiotherapist. She worked for a while in a hospital as part of a chronic pain management team. She used to tell me about pain channels, about how once a body has felt pain for too long in one spot it will find it very hard to forget. The nerves running up and down between the injury and the brain will not know how to stop running, they will perform pain every moment, regardless of whether the injury has healed or not. And maybe this is how it works with love, and devotion, and care. Once you have felt a baby's crying in your own body it is very hard to stop feeling it, even once your baby has grown up. This is how empathy works, isn't it? When we see someone get hurt our brain starts sparking and trembling in the same place it would if it was our own body that was suffering the pain. I like the fleshiness of this, the idea that thought and feeling are so tangled up together in the body. And I like the idea that empathy can be measured, that it can be seen with an MRI, that you can actually see hormones doing a jig somewhere, deep underneath the ribcage.

I read recently that some of a baby's cells can remain in her mother's body, for ever after, even once the baby has been born. It happens the other way too, mother-cells can make their way through the placenta and into her baby's body. And the cells don't just float around in the bloodstream. They get comfortable in the lungs, thyroid, muscles, liver, heart, kidneys and skin. This idea, this phenomenon, of bodies containing the cells of genetically distinct individuals, is called microchimerism, after the fire-breathing Chimera from Greek mythology, a hybrid creature described as part serpent, part lion, part goat.

I'm no scientist. The fine print doesn't interest me particularly. But microchimerism? That got me. In fact I felt as if it had me by the throat, and so I chased it, all the way across the internet, looking at once for proof of my changed bodily self as well as something that would negate it, something that would cut the strings of my maternal body quick-smart.

Microchimerism looked at first like a little rat, its long tail snaking behind it while it scurried through all manner of websites, most all devoted to mother Mary all blue and golden, sitting fatly full of her baby's cells. Microchimerism is, it seems, a useful tool for singing maternal hymns so loudly that there is no way any other stories can be heard. And it fucked me off, so many people sitting smugly with their hands on the biological Bible, so many people using the idea of a particular sort of maternal body to claim that devotion and care are biologically determined.

So I chased the Chimera instead. A Google image search renders the Chimera monstrous. Sometimes it has dragon wings on a lion's body, with a snake's head for a tail. Or it has two or three different heads, or goat horns on a lion's soft face. There are sometimes lightning bolts, always claws. It's always ready to pounce. But it's right there, in amongst all the roaring and the claws, that microchimerism loses it's little rat's tail I think. For the idea of being a Chimera glows a bit, doesn't it? There are possibilities there. Perhaps human beings are not the distinct biological entities we have always imagined. Perhaps the boundaries between self and non-self are not quite as powerful as they seem. Microchimerism encourages an idea of connectedness with other bodies, other selves, so that, quite quickly, I can imagine a future where we understand ourselves not as distinct selves but as chimeras, new types of humans: strange humans. Strange humans with magical bodies, joined together in so many echoes, running on a fuel of empathy and compassion and rage and joy. And this vision is enough for me, I think. It's enough to get through the afternoon.

Chaos

Maybe the future really will be like Fury Road. A parched world, breast milk running through tubes, silver mouths, tumors and scars and everyone going so fast, with the music turned up so loud. It's such a corporeal experience, going to the movies; the bass travelling through the seats and into the viewer's body, all the better to feel as if we are ourselves actually balancing on a pole above a speeding rig, so close to falling off but only wanting to go faster. Remember that feeling? Remember going too fast in a car? Taking too much acid, walking down a too-dark alley? Or, if you prefer, standing in a church in St Petersburg while a choir sings and all you can do is stand with your head back, looking up at all the gold and feeling the music right up inside you, pushing out to the very edges of your skin? Such big feelings, everywhere, there for the taking.

My great-great-aunt Rimor was so devoted to being alive that every morning of the year she would swim in the sea between Denmark and Sweden, in winter cutting a hole in the ice before jumping in. She ate only potatoes and would only talk to my grandparents through the letterbox slot in her front door. She spoke multiple languages, and was a translator for the King of Denmark. My great-great-aunt Rimor was mad, of course, but she was also very clever, and both fearless and fearful. And this seems like real life to me, fearlessness and fearfulness existing simultaneously, either rearing up when we least expect it. It's wild to be alive, after all. There they are, fear and joy and rage, devotion and anxiety, all bound up together like a big pile of snakes. Grab them, I will try very hard to say to my children. Grab all those snakes, for you will see once you are up close that they are not just snakes, oh no. If you look very hard you will see they are actually dolphins diving through a mass of coloured balls. They are transparent luminous creatures on the branches of a tree. They are the weather. And, when you least expect it, you will feel them all, every one, while you are walking along the street with a small hand in yours, light rain falling, gumboots in puddles.