Finding Each Other in the Dark

Every Māori person has, to some extent, a story of loss through colonisation. Te Mauri o Pōhutu speaks to that, gently.

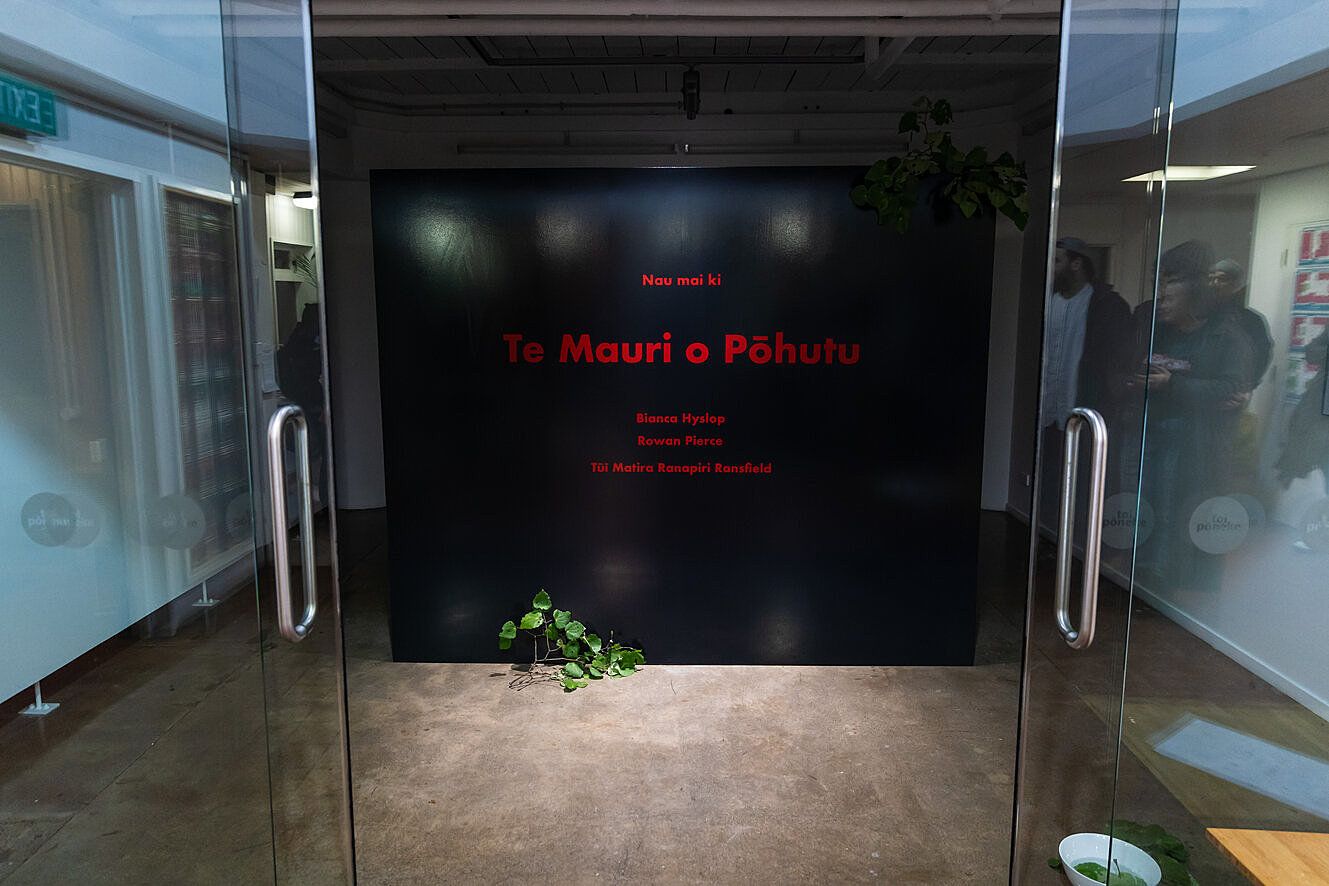

Te Mauri o Pōhutu is a new exhibition at Toi Pōneke as part of the Kia Mau Festival. Bianca Hyslop, Rowan Pierce and Tūī Matira Ranapiri Ransfield have created a series of works that speak about the loss of mātauranga Māori due to cultural assimilation. The exhibition consists of a series of video works and photographs, and a live performance that occurs every Saturday at 2pm. It’s an exhibition based on a previous theatre show. The collection of different elements ensures there is a lot to capture the observer.

Every Māori person has, to some extent or another, a story of loss. Whether this be loss of whenua, loved ones, language, or disconnection from whakapapa and mātauranga Māori, these losses resonate through our lives. The impacts of colonisation are real, personal and specific to each one of us. My nan grew up speaking te reo Māori in the home, but it was beaten out of her at school. She was led to believe that her language was bad, and everything associated with te reo Māori was frightening to her. She didn’t teach te reo to any of her children.

For me, this exhibition speaks to that loss, but gently. The artists grapple with cultural disconnection and the loss of mātauranga Māori through their series of connected video works. This happens, mostly, through movement. In many of the videos, there are people who are reaching out for something, just beyond their grasp. This evokes thoughts of our disconnection from mātauranga Māori, due to our tūpuna, for various reasons, being unable or afraid to pass it on.

Te Mauri o Pōhutu, 2021

The videos play on loop as I arrive, beginning with the sound of children’s voices speaking. We stand in a darkened room as they laugh with each other. One of them squeals, “Ka hoko au i tētahi aihikirīmi!”The others laugh and chatter, “Titiro, he tangata!”

Suddenly, the first video, Penny Diving (2019), appears on the screen. The footage is of the bottom of a murky green river. We are swimming in the river, searching for money. Our hands reach out to feel around in the mud. We find a coin, turn it in our palms, and keep swimming. Our hands are lit in a green light. It’s the sensation of searching that resonates with me here – that we’re looking for something in the depths. For me, the penny we find stands in for the mātauranga the artists are craving to reclaim.

In the next work, Ngā ringa kuia mau ringa moko (2021), we are shown a black space. A kuia’s hand slowly reaches out from the darkness and moves in slow motion across the screen. The kuia’s hand shakes in a strong wiri; the moko’s hand reaches from the other side, tentatively, perhaps unsure of whether there’ll be anything to meet her in the darkness. When the hands finally meet, they grasp each other tightly. The kuia reassures her moko, holding her arm firmly in place. We want what the kuia’s hand offers us. We want all her knowledge and her expertise. We want to remember what mātauranga we have lost. This video ends with the hands being torn away from each other, suddenly, by an invisible force.

The journey towards reclaiming te reo and mātauranga Māori can sometimes feel like swimming blindly in the depths

In the description of this exhibition we learn that Bianca Hyslop’s kuia Ginger is the holder of her family’s mātauranga. Like my own nanny, Ginger is of the generation of Māori who were strongly discouraged from, and even punished for, speaking Māori. Also, like my nanny, Ginger developed Alzheimer’s, which disrupted the possibility of passing her cultural knowledge on. When I see the kuia’s hand breaking away from her moko, I think of our mutual pain at losing the mātauranga of such brilliant tūpuna wāhine.

The journey towards reclaiming te reo and mātauranga Māori can sometimes feel like swimming blindly in the depths. We try to reach out, grasp what we can. But it can be difficult to see clearly in the murk of colonisation. The videos make me reflect on what we’re looking for. I feel as if I’m searching for my ancestors in the dark, asking them to guide me. Sometimes it’s like moving through water. But I’m surprised each time they reach back to take my hand.

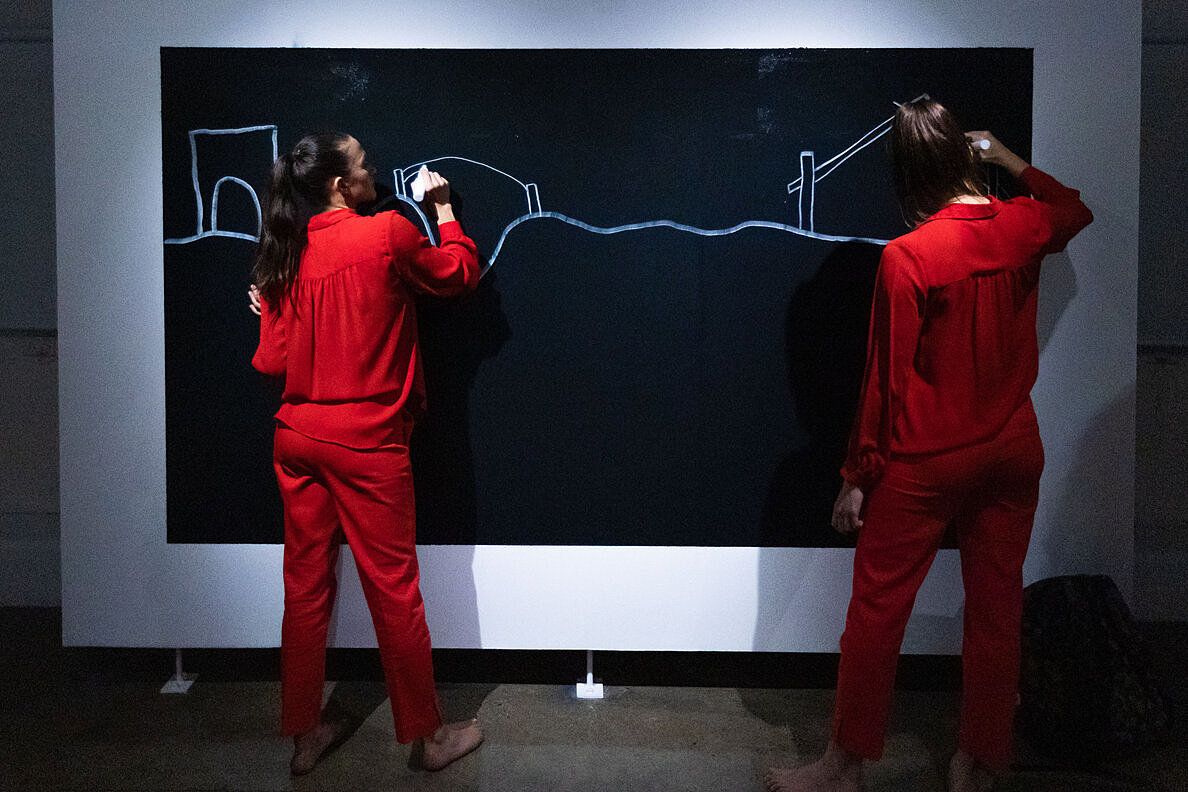

The live-activation movement component of the exhibition involves two dancers dressed in red, moving towards each other. The audience is gathered around them as they begin. At the start, their movements mirror one another. They dance, move closer, embrace and pull away. They move in tandem, mirroring each other’s movements. At one point, before they move to the other designated stage, the two stand at a large blackboard and write on it, Te mauri ka tū, te mauri ka oho, te mauri ka ora, te mauri ka rere.

Bianca Hyslop and Paige Shand, Te Mauri o Pōhutu, 2021

The dancers, Bianca Hyslop and Paige Shand, move past us, barely acknowledging that there’s an audience. They seem to exist in a state of tapu. Perhaps, they are in another world – a place of memory and inner monologue – where only the two of them exist. They move fluidly and elegantly through the space. Their arms reach out for each other in the dark, but also draw away again. Sometimes I think they could be siblings. At other times I imagine they’re two versions of the same person. At other times, they are like lovers, or like an ancestor and descendant.

In the second half of the live activation, a voice overhead begins singing the words that they’d written on the blackboard, Te mauri ka tū, te mauri ka oho, te mauri ka ora, te mauri ka rere, te mauri ka tau. I begin to think that the dancers represent something more profound. That one is the person, and the other is their mauri.

At the end of the live performance, the two dancers move behind a projector screen. A light from behind them projects their shadows, so we can see them moving. Here, at last, they seem to become one magical being, their shadows overlapping and morphing together.

A healer once told me that you can’t help others unless you are first healthy within yourself. Experiencing this show reminded me that to be healthy, we must take care of our entire being – the body, the mind, the wairua and our whānau. And we must also take care of ourselves culturally. Having been in a state of constant stress for the past few weeks, this whakaaro resonated with me. To stay alive, I must take care of myself and my mauri.

Te Mauri o Pōhutu,for me, was an exhibition of healing. It was about reconnection, to our mātauranga, our whenua, our kāinga, the places we belong. The show is full of hope and grace, and a myriad of artworks that will resonate differently with every viewer. But I think that’s a good thing. It feels triumphant. It feels like coming home.

Bianca Hyslop, Rowan Pierce and Tūī Matira Ranapiri Ransfield

Toi Pōneke

9 – 26 June 2021

*

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Kia Mau Festival. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.