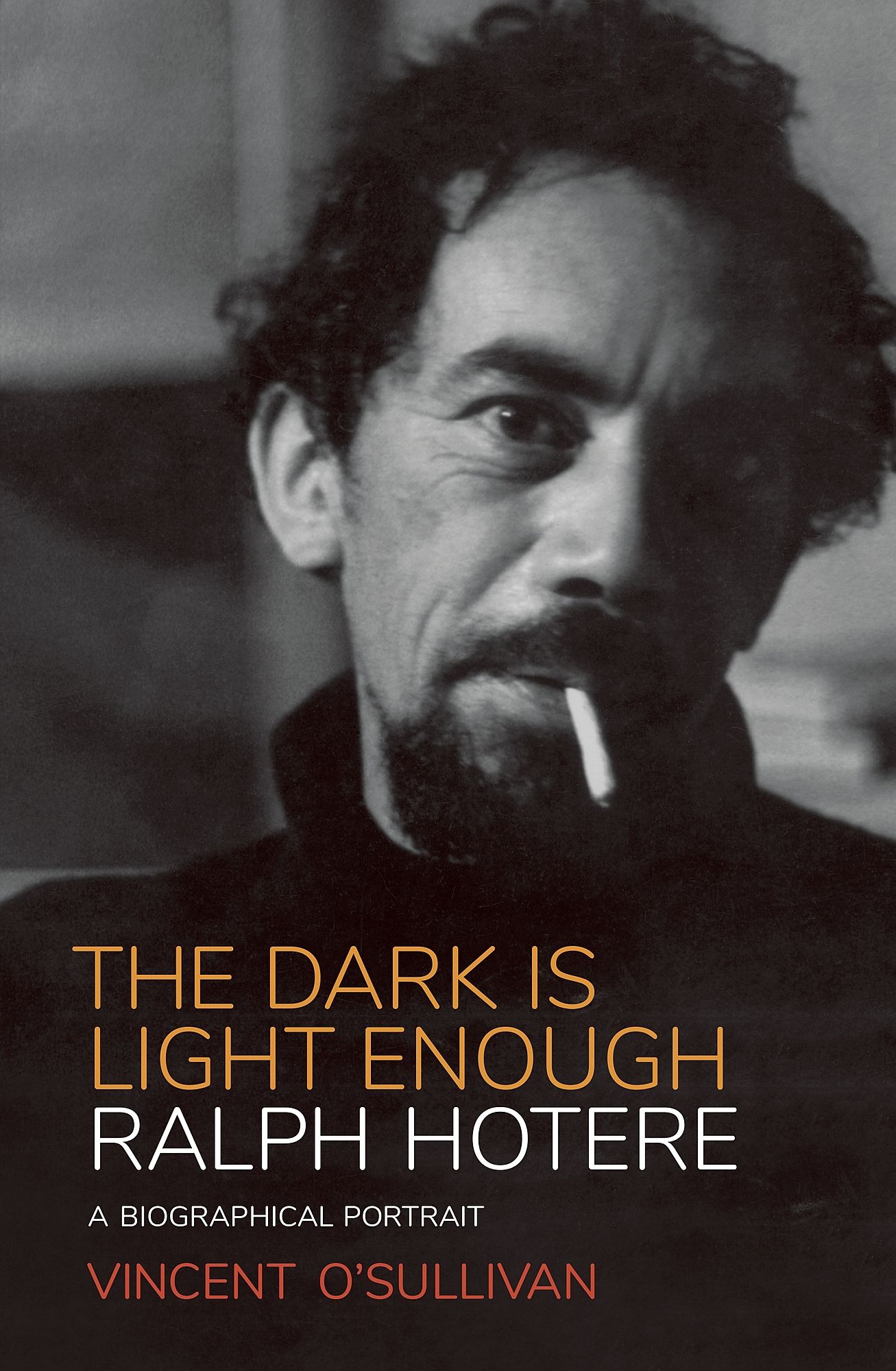

Feast of Riches: A Review of The Dark Is Light Enough

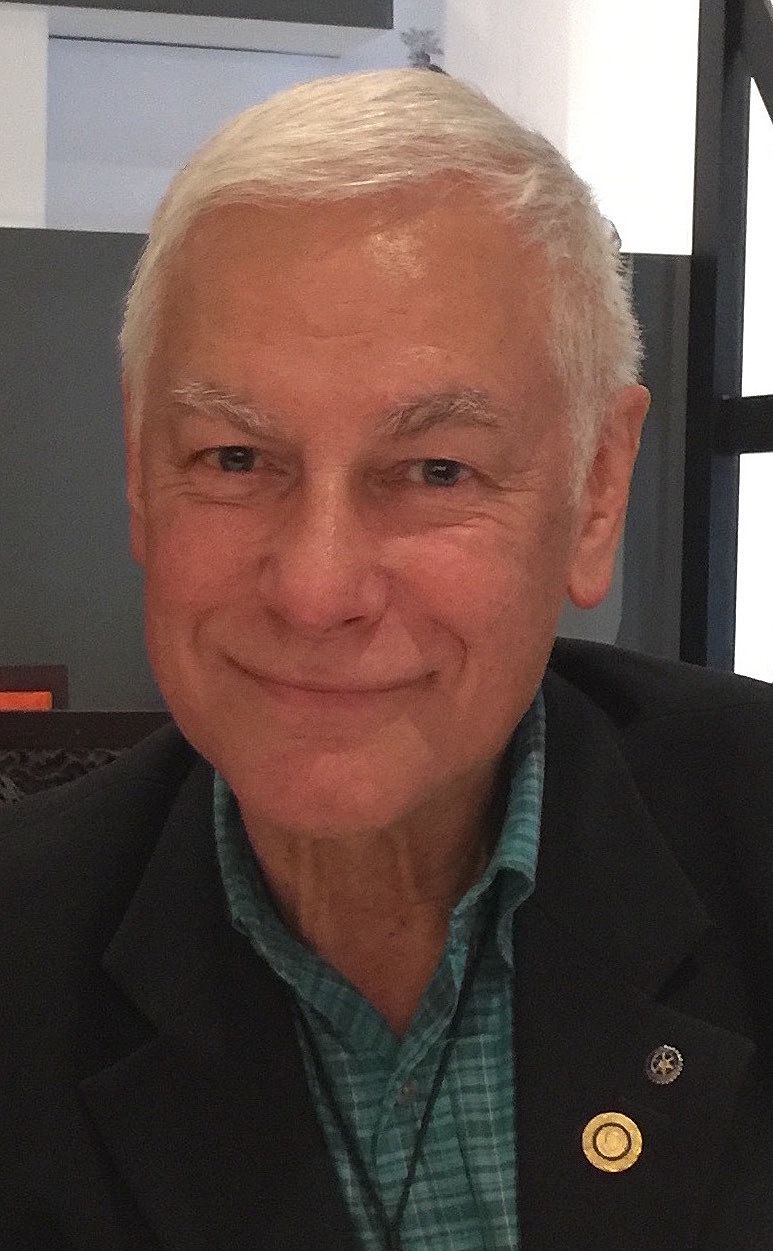

Dr Benjamin Pittman on the richness of the life of Ralph Hotere.

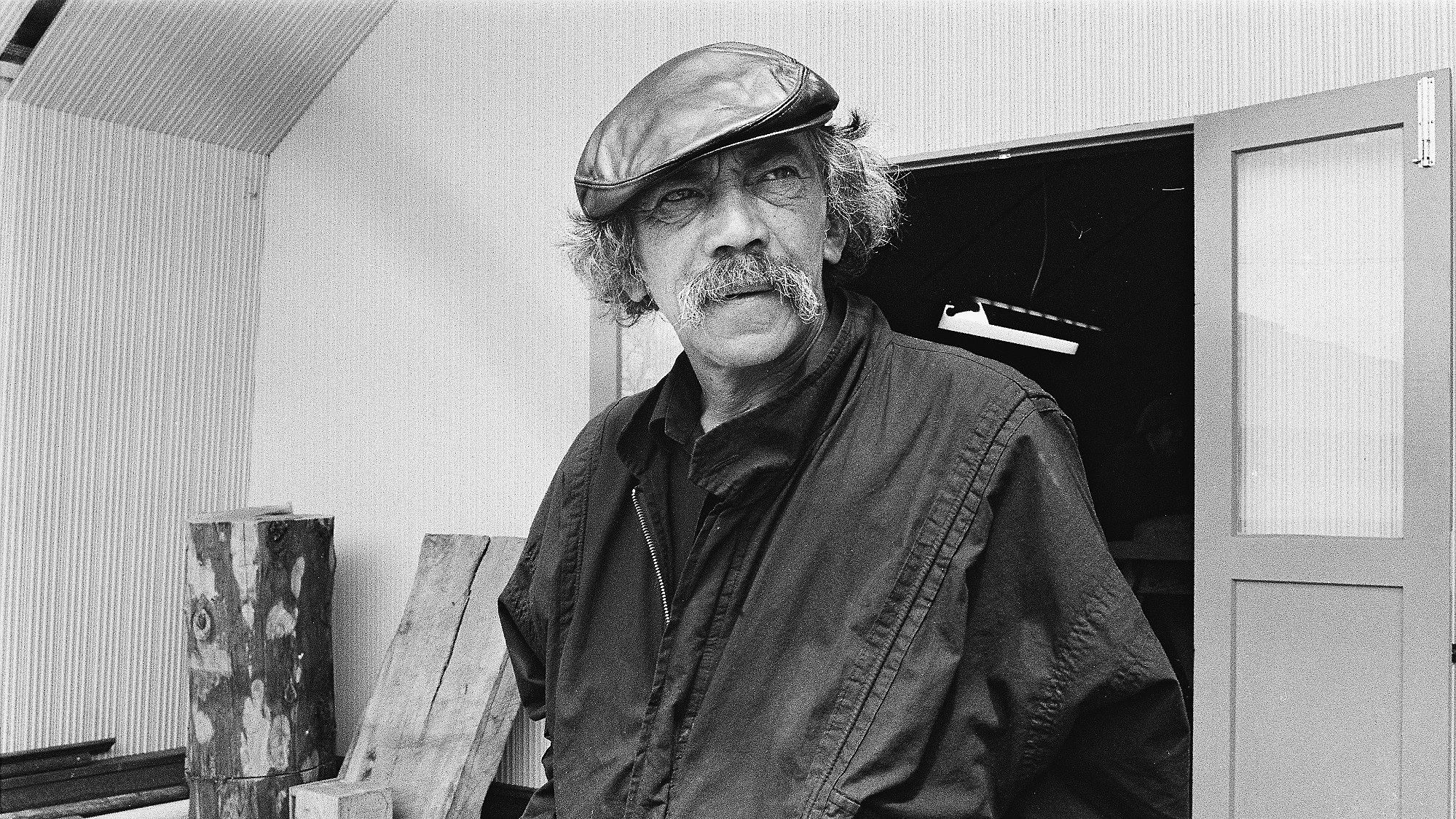

Vincent O’Sullivan’s biographical portrait of Ralph Hotere is a journey in memory and a celebration of a painter’s remarkable life as one of exploration and discovery. I first met Hotere in 1961. I remember especially his grin, and his penetrating eyes. I was 14 and attending Hūkerenui District High School.

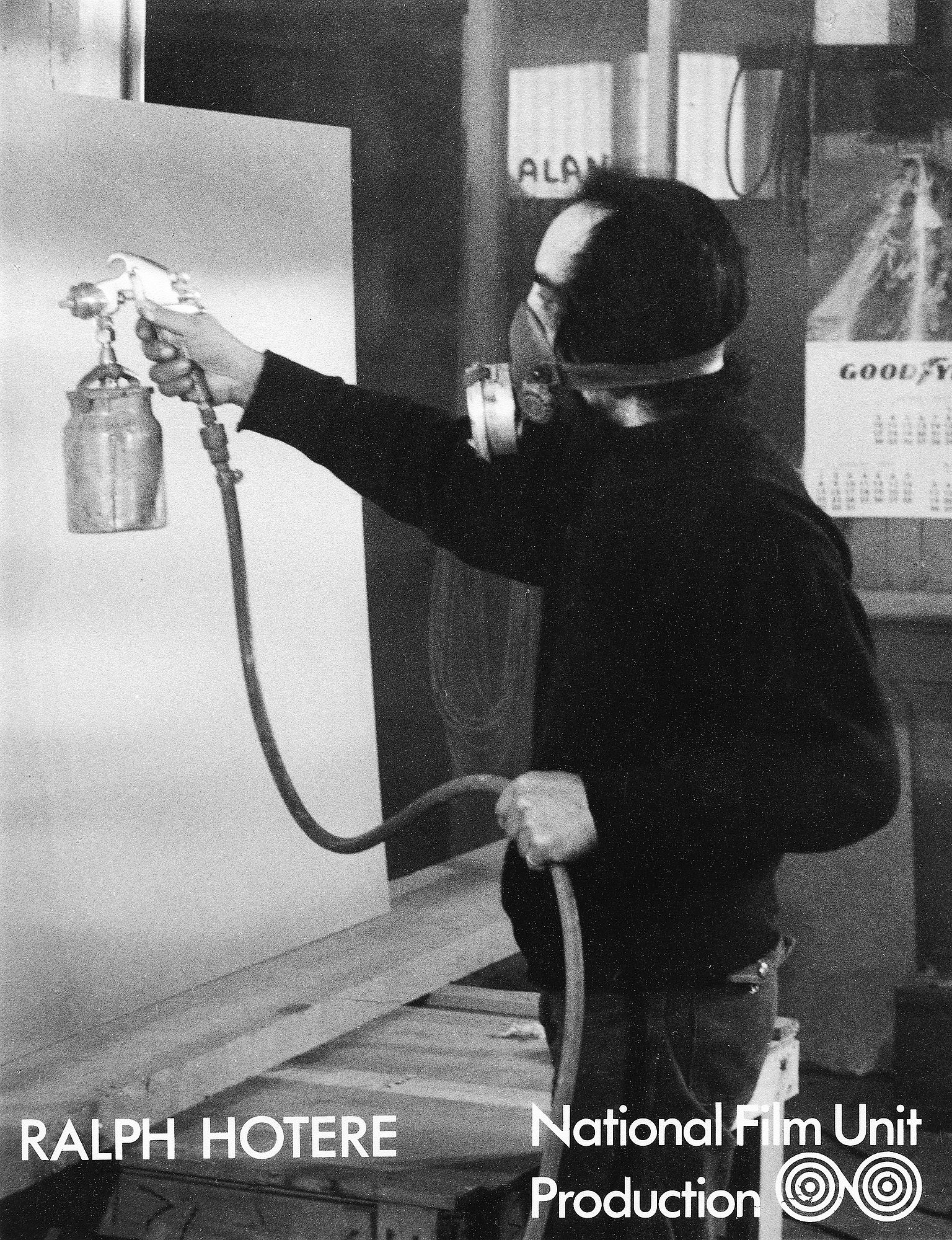

Hotere was not a man of many words, other than with those he knew well. O’Sullivan echoes this in a quote from Hotere: “There are few things I can say about my work that are better than saying nothing.” With this thought in mind, O’Sullivan has not included a single artwork of Hotere’s in this book, except incidentally in two photographs. Although comment has been made on the absence of his works, their conspicuous exclusion does something unexpected. It places the fullest emphasis on Hotere the man.

Through Hotere’s life, O’Sullivan deftly shares a time of significant development in contemporary Māori art, led by Tai Tokerau-based visionaries including Arnold Wilson, Selwyn Wilson, Kāterina Mataira, Muru Walters and Pauline Yearbury. From this we get a sense that the aforementioned artists were not so much developing a movement deliberately but instead, through their work, exploring and pushing creative boundaries as Māori artists, within a context of tradition. This was to trigger many discussions about what constituted Māori art.

In the case of Selwyn Wilson, Arnold Wilson, Kāterina Mataira and Muru Walters, we find they exercised another critical, influential and developmental role as teachers. Selwyn Wilson and Kāterina Mataira at Northland College in Kaikohe and Kaitāia College, Muru Walters at Kaitāia and Arnold Wilson at Bay of Islands College, Kawakawa. Adding to the artistic vitality of the north were visiting arts advisors and other significant teachers like Jim Allen at Kaitāia College, a close friend of Arnold’s, Selwyn’s, and Hotere’s. By carefully bringing together the details of these links and connections, O’Sullivan weaves a web for the reader, one representative of the whakapapa of Hotere’s artistic development.

Meeting houses in the north were generally unadorned

There were also essential enablers like Matiu Te Hau, who looked after Māori adult education at The University of Auckland and David James, the regional adult education tutor for Northland. James organised many meaningful art workshops and brought together diverse artists as tutors. I especially remember the potters Jack Laird and Wailin Hing, and a significant, extended painting and drawing workshop led by Selwyn Wilson at Whangārei Intermediate School in 1962. When it came to defining his space, these people were all part of Hotere’s broader world in the north.

In reading this text, I was reminded that location, of itself, was interesting for another reason: meeting houses in the north were generally unadorned and so, in a sense, regardless of artists’ awareness of and links to more adorned meeting houses in other parts of the country, local traditions allowed more of a blank, creative canvas.

O’Sullivan’s focus on relationships highlights his own understanding of their importance to Hotere. And throughout the text, they are treated as such. We find that Jim Allen studied sculpture at the Central School of Art in London, the same place Selwyn Wilson studied pottery, although those studies were cut short by his father's death. As was to be the case with Hotere’s own international experiences – including at the Central School of Art, and triggered by conversations with Allen – awareness of the arts on a more global stage was critical for all as individuals but equally in a collective sense, and was to have an increasing impact on New Zealand art.

These threads were further enhanced by artists like Robert Ellis and Louise Henderson. All were to become – along with Hotere himself – central to moving New Zealand art into a new and exciting international era. It was not merely about ‘doing’ but also about suggesting and opening up endless possibilities. Through O’Sullivan’s writing, I felt a subtle moment of realisation – that the austere, controlling and stuffy days of the academy at that time were numbered.

Understanding Hotere is about acknowledging contexts, time and place

.

All of this is important in presenting Hotere’s life and significant contributions to New Zealand art, both as a major contemporary Māori artist and a New Zealand artist. Understanding Hotere is about acknowledging contexts, time and place, beginning with his growing up in Mitimiti and its surrounds, where self-sufficiency and hard work were defining parameters. O’Sullivan generously gives much of this context.

The influence of the Catholic Church and its traditions were also pervasive, newly interwoven with tikanga Māori. For Hotere, it was thus the start of weaving a new cloak as a rich and warm gathering of multiple threads of people, ideas, history, identity, relationships and defining influences. This includes certain key events and elements in Hotere’s life: the death in Italy of his older brother, Jack, in December 1943 and then later the deaths of his parents, Ana Maria and Tangirau, events reflected in his paintings. There is also the story of how Rau became Ralph, a journey shared by many others of Hotere’s generation and before.

Within all of this, O'Sullivan's sensitive and inclusive writing comes from a friend's perspective, selected and tasked to do the job by the artist himself. At once, it tells many interwoven stories with deep insight and superb sensitivity and is reflective of Hotere the man and his generosity in every sense of the word. O'Sullivan has woven much of his book around the concept of whānau, indeed in a Māori sense but more widely to include all who have been an important part of Hotere's life. Having known so many of those mentioned, the scope and richness are palpable and deeply satisfying for this reader.

Much more could be shared from within this, O'Sullivan's feast of riches; the anecdotes, events and people. But, as is true of any feast, it is up to those who partake to sample, savour and enjoy, all in a very personal way, as I have.

.

The Dark Is Light Enough: Ralph Hotere – A Biographical Portrait, by Vincent O’Sullivan, is published by Penguin.