Failing to Care: NZ's Public Health System and our Transgender Communities

“If you’re basically afraid of the health system, then you’re not receiving equitable care.”

“If you’re basically afraid of the health system, then you’re not receiving equitable care.”

Ten years have passed since the publication of the New Zealand Human Rights Commission's 2008 document To Be Who I Am: Report of the Inquiry into Discrimination Experienced by Transgender People. New Zealand’s public healthcare system is still failing to adequately meet the needs of our transgender communities.

To say our system is failing isn’t an incendiary claim. At every level of healthcare, it’s the reality experienced by many transgender patients attempting to navigate our public systems. It’s also the reality that was systematically and explicitly outlined a decade ago in the report where, amongst other disheartening findings about inconsistent and poor standards of care, the Human Rights Commission found “major gaps in availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of medical services required by a trans person seeking to transition.”

To say our system is failing isn’t an incendiary claim

When Amanda Ashley, a transgender woman, and her wife Lisa started looking for information about how to receive hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in October last year, they too experienced inconsistencies in responses from service providers. Of the twelve different general practitioner (GP) clinics in the Rodney District that they contacted, two were supportive and interested in improving their ability to care for LGBTQI clients, but many, despite multiple follow-up emails, did not bother to respond.

Lisa also says that several practices specifically stated that their doctors had neither knowledge nor experience in this area, nor had the intention of broadening their scope of practice to encompass transgender health. Ahi Wi-Hongi, National Coordinator of Gender Minorities Aotearoa, says this is a common occurence for the transgender community, “Most trans people don’t expect their provider to be supportive, let alone competent….For the most part, the providers just don’t know anything about trans people.”

The situation can be much worse in provincial and rural areas of Aotearoa New Zealand, where there are fewer GPs and specialists, and long waiting times for appointments. That means, for transgender people who don’t have the financial means to travel long distances to trans-friendly healthcare professionals with expertise in managing their health needs, there are limited options. These involve engaging with local services where they risk discrimination, psychological trauma associated with being misgendered, and with receiving incompetent care; forgoing accessing healthcare services altogether and desisting in their efforts to make their bodies align with their gender identity; or paying for services from the private sector.

“If you’re basically afraid of the health system, then you’re not receiving equitable care,” says Duncan Matthews, Project Manager of the Northern Region Transgender Health Work Plan (a joint regional project involving the Northland, Waitemata, Auckland and Counties Manukau District Health Boards [DHBs]). “That’s not a unique problem to transgender people, but it doesn’t make the problem any easier or different to solve than [those of] other minority populations.”

*

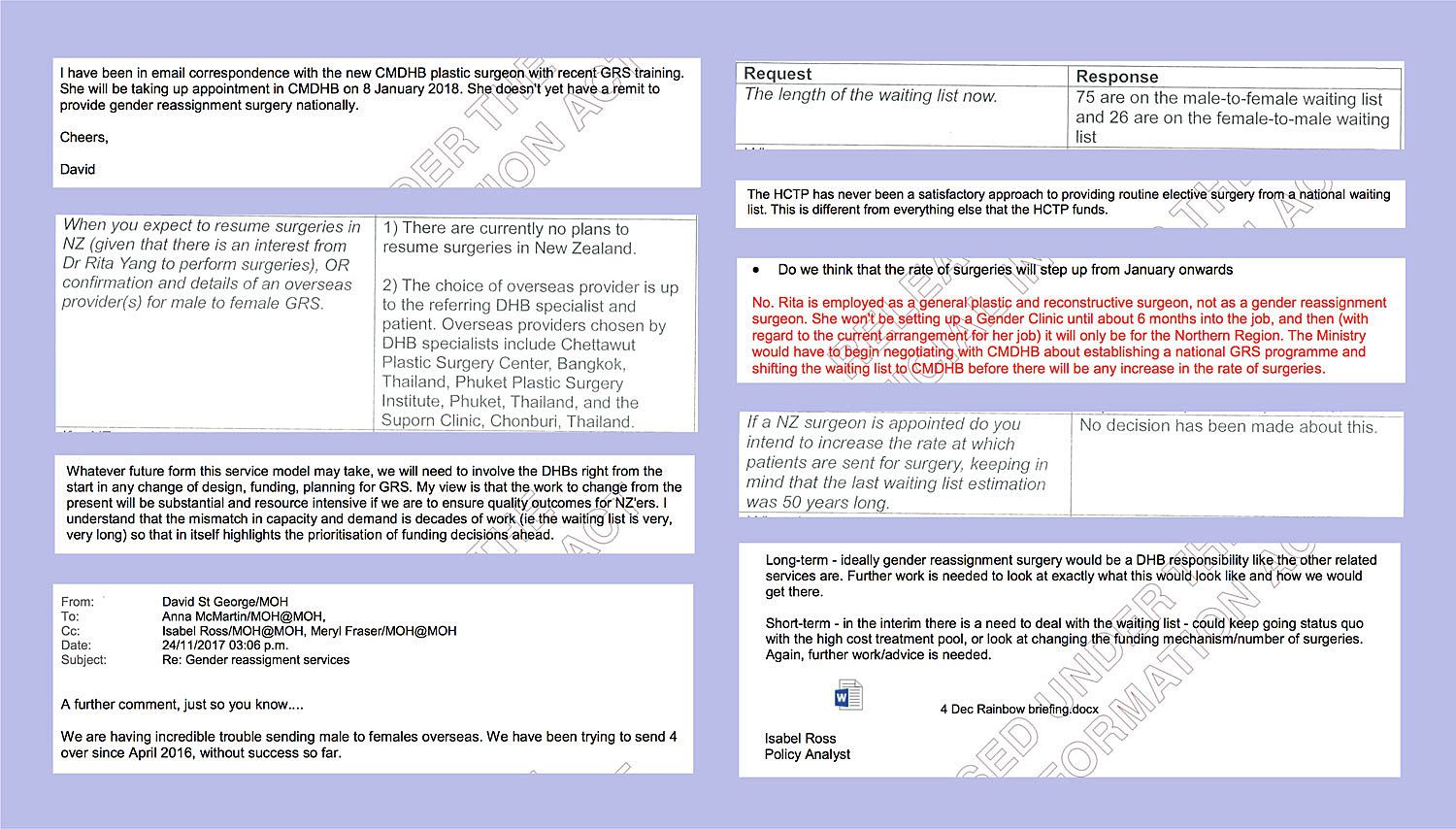

Not all people who identify as being transgender want to have gender reassignment surgery (GRS). But for the many who do, it is near impossible to access through the New Zealand healthcare system. Information released under the Official Information Act from the Ministry of Health this year reveals that, as of March 2018, there are 75 people on the male-to-female waiting list, and 26 on the female-to-male. This is likely an underestimation of the true demand for these surgeries, as many transgender people don’t go through the process of getting themselves on these lists; it’s seen by many as a fruitless endeavour.

The truth is that this ‘waiting list’ is a misnomer on several levels. Firstly, there has never been a nationally funded GRS service. Traditionally, applications for funding have had to be made to the Ministry of Health’s High Cost Treatment Pool, with successful applicants receiving their procedures in the private sector, either in Aotearoa New Zealand or overseas in the case of all female-to-male surgeries. Secondly, the word ‘waiting’ gives the impression that these procedures are within realistic reach for those who join the queue. However, even before Mr. Peter Walker (until this year, New Zealand’s only plastic surgeon with the expertise to perform GRS) retired in 2014, only one female-to-male and three male-to-female surgeries were funded every two years. For a transgender woman who meets the eligibility criteria to be added to this list today, that would be a minimum wait of 50 years.

In the first year of medical school, we are encouraged to critically deconstruct what good healthcare accessibility means. There are many ways of defining meaningful access, and multiple determinants that influence its realisation: affordability, availability, geographical accessibility, accommodation and acceptability.[1] With respect to GRS, there are many complex issues in each of these dimensions of access that are significant impediments to timely and appropriate service provision.

Some of the larger problems revolve around the funding model and surgical infrastructure. The Ministry of Health knows that the current system of providing GRS is highly inefficient and unsustainable. In an internal email, Chief Advisor of Integrated Health Dr. David St. George wrote about the “incredible trouble sending male to females overseas. We have been trying to send 4 over since April 2016, without success so far.”

The challenges and delays to this system of sending patients overseas for major operations are numerous: some patients have relocated over the years to smaller DHBs that are more reluctant to engage in the process; a patient and support person taking a month off work to go overseas presents considerable hurdles; and some patients require preoperative reassessment as they haven’t been seen for a decade. “All of this points to the need to establish a service in NZ,” concludes Dr. St. George’s message.

Nearly every transgender patient and ally I’ve spoken with said that the state of being transgender, and the accompanying need to take hormones or undergo surgery, is widely perceived as “just a vanity exercise,” or a lifestyle choice by doctors and members of the public alike

Furthermore, though not mentioned by Dr. St. George in his email, some transgender patients are deterred by the current requirement to go overseas to receive profoundly life-changing operations. Overseas medical systems like Thailand’s, which has many of the world’s most experienced experts and pioneers in GRS, may provide excellent operative care, however some transgender people find the prospect of going overseas and the lack of continuity of care once they return to Aotearoa very daunting. Melonie is one such person and says, “There’s no way I want to leave New Zealand...to have major surgery like that…It’s much better to have your family around...at least your friends or something. Taking somebody to Thailand to accompany you, that adds to the cost of doing things…and then flying back after just having major surgery…obviously people have done it many times but it does sound sort of dangerous and a little foolhardy to go and have major surgery and then go on a flight back again.”

The MoH appears to be considering several potential options of what the service infrastructure may look like, with each option requiring exploration, including discussions and negotiations with potential providers. One of these options involves Dr. Rita Yang, New Zealand’s only plastic surgeon with training in GRS, who is currently employed at Counties Manukau DHB.

Ultimately, the internal MoH emails show that plans for improvements to publicly-funded GRS provision are still in their nascent stages. This seems incongruous, however, with the indicative timeframe (by 1 January 2019) within which the Northern Region Transgender Health Work Plan 2017 aims to achieve the objective “wait list times for surgery are reasonable.” So how do the MoH’s plans fit in with those of the four DHBs that are part of this Northland project? What are some of the barriers from the DHBs’ perspectives with regards to rolling out a GRS service?

“It’s just all a big mess with everybody on different pages,” says Duncan Matthews. “I’ll be the first one to admit that [the indicative timeframe] was optimistic…The biggest thing which the Auckland DHBs are worried about, and it’s been happening since day one, is that if we make GRS available in Auckland, then what’s going to happen is a whole bunch of people are going to suddenly find that they live at level 1 number 11 Edinburgh Street (which is the Rainbow Youth centre in Auckland) so that they can access these surgeries. So the DHB is really keen to do it in partnership with the Ministry of Health slash force the other DHBs to do it, or buy the procedures from Auckland so that Auckland doesn’t end up wearing the cost for everybody in New Zealand who wants these procedures. I think that’s one of the biggest concerns.”

During our conversation about transgender healthcare accessibility, there’s a moment when Matthews expresses frustration at all the other factors that are outside his or any member of the transgender community’s ability to control. He makes a grim joke about the state of the leaking and mouldy Middlemore Hospital buildings being another barrier to creating a surgical service, before adding “in all seriousness, my understanding was that theatre time was basically maxed out in Counties for the plastics service as is…so even the ability for Rita to book theatre time to do some of these procedures would be difficult.”

*

Advocates for transgender patients often frame their reasoning behind the imperative need for improvements in healthcare and surgical care accessibility in the context of human rights and equity. International standards of care provide clear medical justifications for providing both HRT and GRS, the latter of which is a necessary and effective pathway for some transgender patients that enables them to live fully in their gender identities. If our healthcare system thus fails to make either of these services accessible to all transgender patients, it is infringing these patients’ human rights to appropriate healthcare.

However, too often advocates find these arguments hold little credence with many New Zealanders. Nearly every transgender patient and ally I’ve spoken with said that the state of being transgender, and the accompanying need to take hormones or undergo surgery, is widely perceived as “just a vanity exercise,” or a lifestyle choice by doctors and members of the public alike. Based on assumptions like these, strong objections arise to any publicly funded services for transgender-specific needs.

“People always view giving money to transgender health as taking away from something else”

“People always view giving money to transgender health as taking away from something else,” says Matthews, who has used inequity in access arguments in funding proposals for transgender surgical procedures in the past. He acknowledges that the decision determining what groups of patients, and how many of each kind, should receive funding for the same surgical procedures (such as mastectomies and hysterectomies) is a difficult call to make if the various patient groups all have genuine clinical needs. However, he feels that transgender patients have to battle a double layer of difficulty in receiving funding for life-affirming procedures, due to discrimination and the misconception that being transgender is a choice (thus putting the onus on transgender people to pay for the procedures that facilitate these ‘decisions’).

Lisa Ashley is particularly baffled by people who see her wife’s being transgender as a choice. “Because who is going to choose to have such a difficult life? Willingly? And we have to go out places...people stare at us...sometimes we get comments...Who’s going to choose that? You know? It’s like putting a label on yourself.”

Moving forward, Duncan Matthews hopes to also include health economic analyses in future proposals to DHBs for increased funding for gender-affirming surgeries. He believes that communicating the value obtained through these procedures via measures such as Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY) will help gain traction in acquiring further funding. QALY is a unit used in analyses of the cost-effectiveness of health interventions, which is calculated based on the understanding that health is a function of both duration and quality of life (1 QALY = 1 year lived in perfect health). Though there aren’t many studies analysing the economics of gender-affirming surgeries or GRS, Matthews says it’s very easy to argue that even with the most conservative estimates of improvement in quality of life per year, this value becomes very significant over the multiple decades of transgender patients’ lives.

Of course, there are limitations to using yardsticks such as QALY-based values, and the way our country should spend on medical care has always been, and will continue to be, hotly debated. And while quantitative analyses may be instrumental in championing various investments such as transgender healthcare and surgical services, it is important to remember that ours is not a system that is wholly numbers-driven. As do many other countries’ health systems, we fund a range of costly medications and interventions for a range of diseases despite these decisions not being very economic; in line with the vision of the World Health Organisation’s 1946 constitution, our healthcare system strives to uphold patients’ dignity and honour their fundamental rights to “the highest attainable standard of health.”

*

In introducing an aspect of an empathy-driven approach to healthcare planning and allocation, however, we also introduce inequality into our healthcare systems. Empathy is malleable, after all, and susceptible to bias. In this manner, pervasive societal beliefs about gender and those who do not fit neatly within prevalent, socially-constructed understandings of gender (some of which have been described above) can have far-reaching impacts on the health of our transgender community.

One such pervasive ideology formally perpetuated by Western medical systems is that of the transgender identity and experience being a state of pathology. Though the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) updated the previous DSM-4 diagnostic label of gender identity disorder to exclude the term ‘disorder’ in a symbolic shift, the new label of gender dysphoria is still a psychiatric diagnosis. This updated diagnosis does little to challenge the widespread supposition of transgender identity as a psychiatric illness, one that necessitates medical interventions such as psychotherapy, hormone therapy, and surgery.[2] It also continues to subject transgender patients to explicit and implicit stigma toward mental illness on multiple levels, from the level of the individual to the institutional. Stigma about mental illness has known pernicious effects in preventing people from accessing services, limiting people’s opportunities in life, poorer quality of care for people with mental illness, and on the lower prioritisation for public resources allocated to mental-health services.[3]

In an article on the influence of the medical model on transgender identities and experiences, Austin Johnson writes that the medical authority over gender variance via continued psychiatric diagnoses has resulted in the development of a hegemonic medical model of the trans experience of gender:

“Positioning transgender experience and identity within the medical model creates the following three‐step process of becoming transgender: (i) experiencing discomfort and distress surrounding gender throughout life; (ii) acquiring a psychiatric diagnosis for gender variance; and (iii) accessing gender‐affirming medical interventions. While the content of the diagnosis, in terms of language used and descriptions given, has shifted over time to be less damning of transgender people, the form of the diagnosis has continued to sustain this narrowly defined process of transgender identity.”[4]

The diagnosis of gender dysphoria and the prescriptive narratives of the transgender experience as defined by this medical model can undermine the autonomy of transgender people in two significant ways. Firstly, it absolves society from considering and reflecting on its complicity in perpetuating gender ideology, transphobia, or cissexism, by concentrating on embodiment as being the root of distress around misalignment between a person’s assigned sex and gender identity. Secondly, many transgender people will internalise the pathologising world views about their own identities that are so heavily built into this model’s architecture.

Many transgender people, advocates and researchers see the latter point as a necessary compromise within the current medical systems they navigate. A diagnosis, however harmful to the transgender self-concept, is formal recognition of medical needs and can be crucial for facilitating access to services and medical insurance. Professor Judith Butler of the University of California, Berkeley, believes that this paradox of bodily autonomy for transgender people – in which “the diagnosis leads the way to the alleviation of suffering” yet “the diagnosis intensifies the very suffering that requires alleviation” – requires considerable changes in our society’s thinking:

“...the norms that govern how we understand the relation between gender identity and mental health would have to change radically, so that economic and legal institutions would recognize how essential becoming a gender is to one’s very sense of personhood, one’s sense of well-being, one’s possibility to flourish as a bodily being. Until that time, freedom will require unfreedom, and autonomy is implicated in subjection. If the social world must change for autonomy to become possible, then individual choice will prove to have meaning only in the context of a more radical social change.”[5]

*

Yet there are some changes – many changes – that can and need to be made now. Dr. Jo Scott-Jones, a GP in Opotiki and medical director at Pinnacle Midlands Health Network, wrote an article in NZ Doctor last April following a session listening to LGBT patient representatives about the LGBT community’s experiences of health services in the Waikato region. Many transgender patients face numerous barriers in their attempts to access basic healthcare. Dr. Scott-Jones wrote that the stories that emerged in this session were “...a depressing reflection on the state of primary care, an indictment of our attitudes and skills, and a description of the multiple barriers gender-diverse people experience when they try to access basic primary health services.”

As humans, we all have internal biases and prejudices. Acknowledging these, unravelling them when and where we can, and working on minimising their impact on our patient care should be part of every healthcare worker’s ongoing professional commitments

As humans, we all have internal biases and prejudices. Acknowledging these, unravelling them when and where we can, and working on minimising their impact on our patient care should be part of every healthcare worker’s ongoing professional commitments. Dr. Scott-Jones concluded in her article: “Failing to learn how to overcome our innate prejudices, failing to learn how to talk about intimate and personal behaviours and issues, and failing to learn how to be non-judgemental and respectful of everyone is not an option if you are a GP.”

However, as Taine Polkinghorne, a trans man and human rights advisor for sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics for the Human Rights Commission, stated in an NZ Herald op-ed earlier this year, while we are exiting a period of trans erasure “we are not yet entering a period of trans visibility.” The implication of this for the medical sector is that most members comprising our workforce will require education and training in order to unpack the stereotypes and misinformation we have acquired throughout our lives, and to develop the cultural competencies necessary to provide services that empower, rather than harm, our patients.”

*

Which subtends another question: what kind of education, how much, and at what stage(s) of training?

According to Professor Warwick Bagg, Head of the Medical Programme at the University of Auckland, transgender health-related content in the current curriculum in the School of Medicine is covered during two lectures on “Medicine and LGBTQI People,” small group tutorials focusing on a discussion of issues presented in these lectures, one “Sexualities and Inclusivity” lecture (in addition to a general “Sexual History Taking” lecture), one sexual health small-group tutorial including LGBTQI-inclusive cases, and an optional medical humanities paper in gender studies (“Sexuality, Gender, and Sex Diversity: Queering healthcare”) in the third year. Some students feel that the quality and quantity of teaching about transgender health is insufficient. One student, who asked not to be named, said that although the non-optional lectures and tutorials outlined above do technically touch on some aspects of transgender health, “the emphasis isn’t really on transgender patients.”

When asked if there were any barriers towards incorporating transgender-health-related topics into the curriculum, Professor Bagg replied, “There have been no barriers to the changes we have made, other than finding the time in a busy medical programme. As with all areas of medicine, we [are] constantly juggling, managing the overwhelming content, with what is appropriate for undergraduate learning and what might be better taught in postgraduate settings.” Jen Desrosiers, who teaches the public health module for medical students at the University of Otago, also says that the barrier to increasing the quantity of undergraduate teaching about transgender health is primarily to do with curriculum time. “We have a full curriculum, and it has been (but is no longer) a struggle to make the space for this curriculum. Also, this is a relatively new area for research and practice, so there is not a robust evidence base for best practice.”[6]

The transgender-health-related content in the Otago Medical School curriculum is covered during four hours of total contact time set for teaching about gender diversity. During these hours, Desrosiers says that students learn about gender as a construct and the relationships between gender and health, spend time at Qtopia (a community group for gender-querying youth), practise asking patients about gender, and learn about the health pathway, where the specifics of health needs, prescribing, gender affirmation surgeries and support systems are discussed via tutorial and role play.

It’s a hopeful sign that some of the institutions training our country’s future medical professionals are increasingly recognising the need to inform students about transgender health issues. Current working professionals, most of whom did not receive any training in their undergraduate degrees, may need to participate in self-directed learning for a while longer, though there are efforts to make relevant education available via the DHBs.

Part of the legacy Duncan Matthews hopes to help build during his time as Project Manager of the Northern Region Transgender Health Work Plan is to make online education modules on cultural sensitivity when engaging with transgender patients a permanent part of the DHB staff websites. “Changing it through the DHBs, having those training modules and information available, the DHB being in the pride parade…is part of changing the culture of New Zealand as well as the culture of the DHBs.”

[1] Penchansky, R., & Thomas, J. W. (1981). The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care, 19(2), 127-140.

[2] Teich, N. (2012). Transgender 101: A simple guide to a complex issue. New York: Columbia University Press.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Association of County Behavioral Health & Developmental Disability Directors, National Institute of Mental Health, The Carter Center Mental Health Program. (2012). Attitudes toward mental illness: Results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[4] Johnson, A. H. (2015) Normative accountability: How the medical model influences transgender identities and experiences. Sociology Compass, 9, 803-813. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12297.

[5] Butler, J. (2006) Undiagnosing gender. In P. Currah, R. M. Juang & S. P. Minter (Eds.), Transgender rights (pp. 274-298). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[6] Desrosiers, J., Wilkinson, T., Abel, G., & Pitama, S. (2016). Curricular initiatives that enhance student knowledge and perceptions of sexual and gender minority groups: A critical interpretive synthesis. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 7(2), e121-e138.

The lack of a robust evidence base for what might comprise an optimal curriculum for tertiary students to increase their knowledge and skills to care for sexually- and gender- diverse groups was a finding in this review paper published by Desrosiers and colleagues, which was used as a framework for developing the current curriculum at the University of Otago.