Writing on the Wall? Fascism and Antifa Presence on the Streets of Eastern Europe.

Murdoch Stephens travelled through Eastern Europe documenting the clash of ideology between the far right and the antifascist (Antifa) left as it appeared in and through street art

Murdoch Stephens travelled through Eastern Europe documenting the clash of ideology between the far right and the antifascist (Antifa) left as it appeared in and through street art. Content Warning: fascism, violence, faeces, hate speech, sexual imagery.

Radicals sometimes say,

“if you want to understand what's really happening in a society read what's scribbled on the walls, not in the newspapers”.

My first personal encounter of this kind was when some kid from high school tagged the wall of the Dunedin Countdown with a giant “Murdoch Stevens is a faggot”. “Fuck!” I thought... they spelt my name wrong. So one night I went back and changed “Stevens” to “Stephens”. Then I made “faggot” into “phaggot”. Why? To my younger self, it seemed the best way to refuse the absurd blackmail involved in trying to convince a brick wall of my straight credentials. I wanted to both refuse the slur and also to refuse the notion that being queer would be a slur.

And from that moment on I was also a little bit more suspicious of the gallant truth-telling of all that gets written on walls.

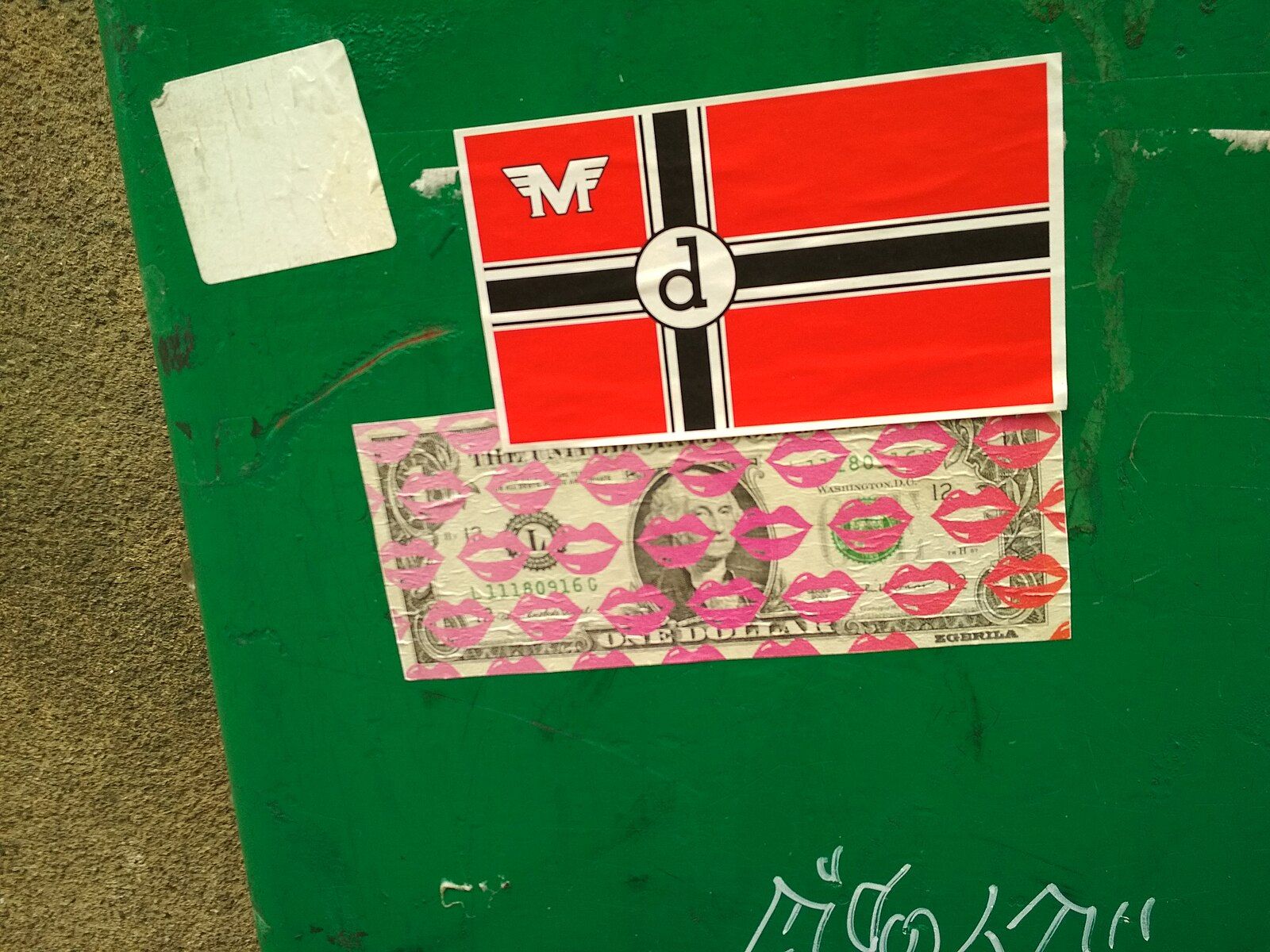

But who are today’s radicals? In the United States and across Europe new forms of far right politics have been emerging and gaining electoral representation. Alt-right, eurosceptic and populist are some of the terms being used to describe a resurgence of far right political forces across Europe, from the AFD in Germany, through UKIP's successful Brexit campaign and the anti-refugee borders constructed in Hungary. While these groups often draw from the fascist imagery and tone of previous far right groups, there are some differences – particularly with the use of irony and memes in the alt-right. The alt-right is an amalgam of old and new forces with no central platform apart from their opposition to some kind of left PC morality.

The alt right claims that today they are the radicals. They see the mainstream as ‘useful idiots’ for ‘cultural Marxists’. ‘Cultural Marxism’ is a term used as an attack against the left by the far right that suggests Marxist ideas – previously most obvious in economic and political circles – are now achieved through causes such as gender equality, gay rights and refugee protection. Cultural Marxism suffers from a 1950s ‘Reds-under-the-bed’ paranoia that sees all forms of advocacy, including mainstream media, as secretly driven by communist aspirations. With such a strong sense of persecution it's no strange thing to find the far right taking to the walls too.

The alt-right is an amalgam of old and new forces with no central platform apart from their opposition to some kind of left PC morality.

Some people don't seem to understand the impulse to contribute to public life by spending money and time on graffiti and street art. There are a few simple reasons: deep ideological commitment to the message being spread, the internal cred you get from tagging communities, or for personal or corporate branding and profit. There are many forms that this street art can take – spray painting, stickering, paste-ups, postering, tagging with a permanent marker and plenty of other imaginative mediums. In this instance, I am lumping them all together under the term 'street art' rather than 'graffiti' – as these two young German folks informed Bryan Crump, street art is focussed on appealing outwards to the public, whereas tagging is focussed inwards on the tagging community.

There's an even simpler answer to why people persist with making these marks in and on the public spaces: people stick stuff up in public places because they can. They have time, money or both. A more sophisticated version of this theory comes from Georges Bataille's The Accursed Share – a work of economic anthropology and theory that starts from questions of what a society does when it has surpluses. He offers two basic answers: we make art and we make war. While much street art aims for the first, that of the fascists and antifa is clearly of the second.

One curious, in between space is that of the Ultras – hardcore football supporters who sometimes stray into far right and nationalist politics. For example the Bad Blue Boys, who support Dinamo Zagreb, are well known for their Croatian nationalism and they use far right imagery in much of their art.

It is difficult to know what Bataille would make of the use of excess energy by the ultras. On the one hand sports unleash conflict through a process that is a proxy for actual violence and though ultras are not supposed to be hooligans there is plenty of crossover. But there is also sport as the exhibition of skillful beauty and limit testing which is more artistic. Unlike in New Zealand, these hardcore supporters use street art to both mark their home turf and to mark where they've been for away games. As with so many theories, the exoskeleton of Bataille’s categorisation is useful to understand how excessive energies can be deployed, but that doesn’t mean it should be used as a binary in which all examples can fit.

I am no fan of the brutish conservatism of the far right nor the facile resentments of the alt-right. The descriptive treatment of these street markings is not based on a lack of personal opinion, but for a preference to avoid premature of empty prescriptions. What is to be done about the far right? I don't have the one answer, especially not for regions that I am only beginning to be familiar with. However, I do think liberal democracy is more resilient than the credit given to it by clickbait driven forms of hyperbolic journalism.

Warsaw, the Polish capital, was recently the host to a 60,000 strong national day march that was used by the far right to make explicit comments for a white Europe which is against refugees. It took a couple of days before the right wing populist Law and Justice party gave a half-hearted rejection of these comments. And yet, on the streets of Krakow, I spotted this strange recurring poster without a smudge of graffiti on it.

How can there be a strong fascist movement but such posters also go up and stay up? It took a visit to Auschwitz to realise that while much of the world sees Auschwitz as a symbol of the concentration camps of Jewish people, in Poland it also signifies the place where thousands of Polish prisoners of war and resistors were murdered. “Reperationen Macht Frei” is not a call for reparations of murdered Jewish people, but of the cost to the Polish. As such it is a nationalist slogan, rather than an anti-fascist one.

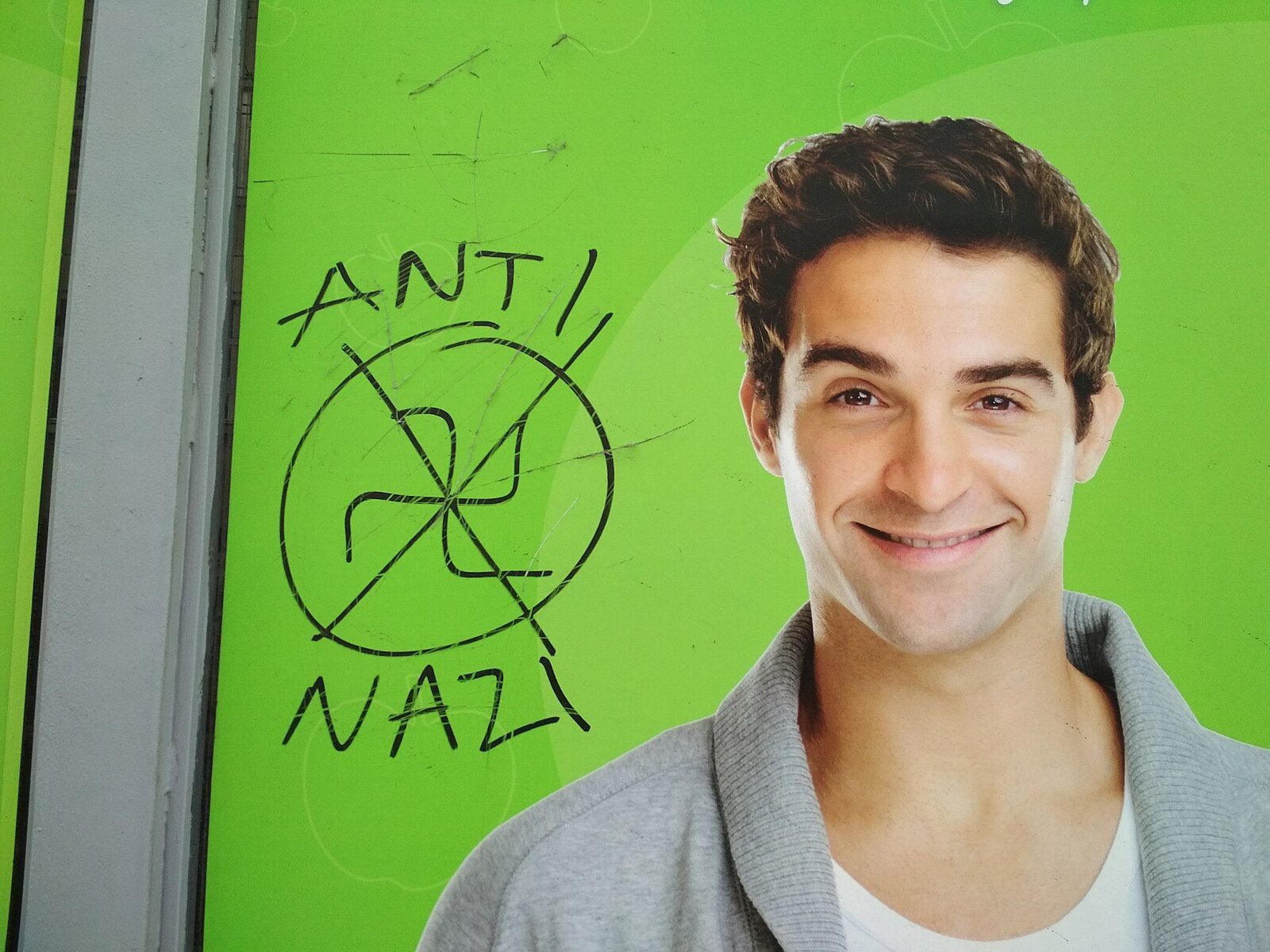

There are also plenty of anti-fascist, though not explicitly Antifa, signs around Krakow, especially in the former Jewish district which is now the hub of student and alternative culture. And yet whenever I see a 'no swastikas' symbol I closely compare the markers used, to see whether the Anti-Nazi intent of the prohibition symbol changed an original swastika or if the swastika was drawn as a part of the no swastika sign. Such are the challenges of negation – to paraphrase Ronald Reagan, “if you’re negating, you’re losing”.

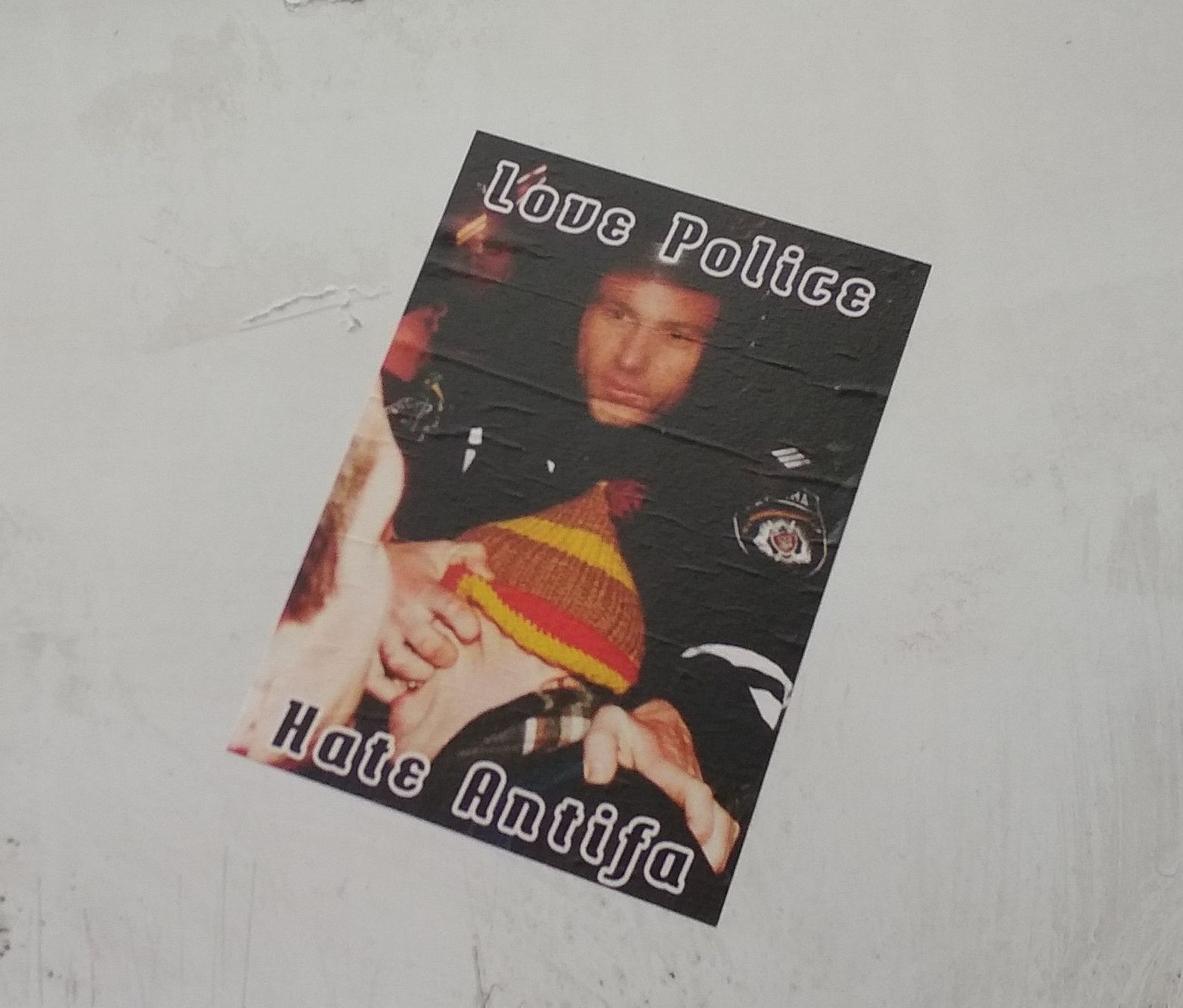

While most Antifa and Ultra are direct about their markings, some stickers made me question whether there was irony involved. Could someone really spend their own money making a non-ironic “Love Police / Hate Antifa” set of stickers?

This doubt quickly dissipates when noticing the sticker next to it. 'Stand Your Ground' has all the Crusader imagery that the far right loves, combining it with a reference to the 'stand your ground' language popularised in US gun control circles. Saint Michael may well be a reference to the Romanian fascist group 'The Legion of the Archangel Michael', otherwise known as the Iron Guard.

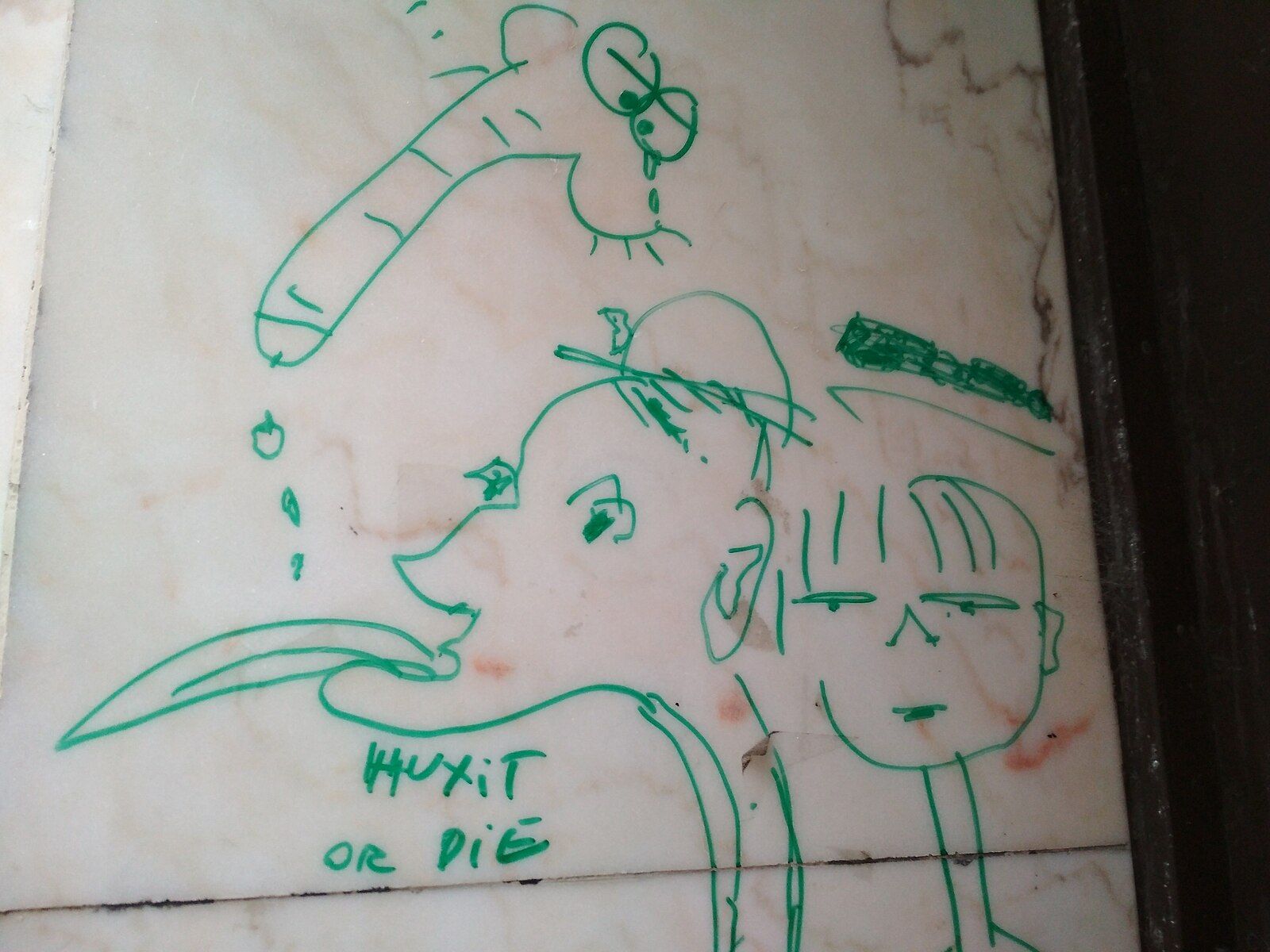

The troll-play of the alt-right can be seen in the wishes of many within other european states to have their own exit from the European Union (EU). “Hungary should have Huxit” (an already cliched , word play on the term Brexit), they suggest.

To the south, in Croatia and Slovenia, there is not the same right wing populist governments (despite some graffiti). I was particularly charmed by the anti-U graffiti of Zagreb where faint and messy signs gave the impression of a giant child, like Trump, making their first attempt at street art.

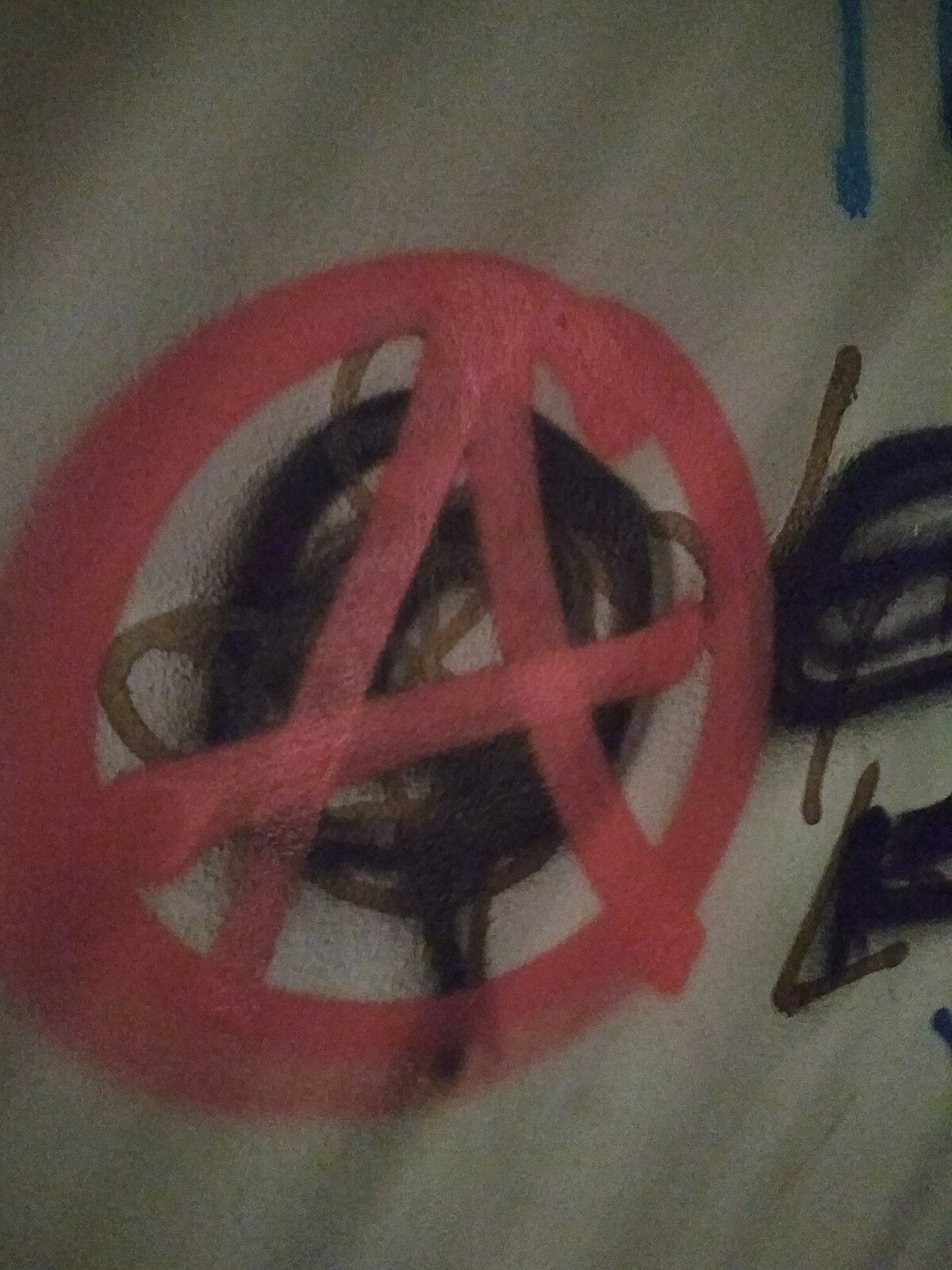

The streets of Zagreb and Ljubljana have much more Antifa presence. The traditional antagonists of Antifa – corporations, government, formal religion – were all well represented in the street art, though there were also plenty of pro-refugee, anti-border images.

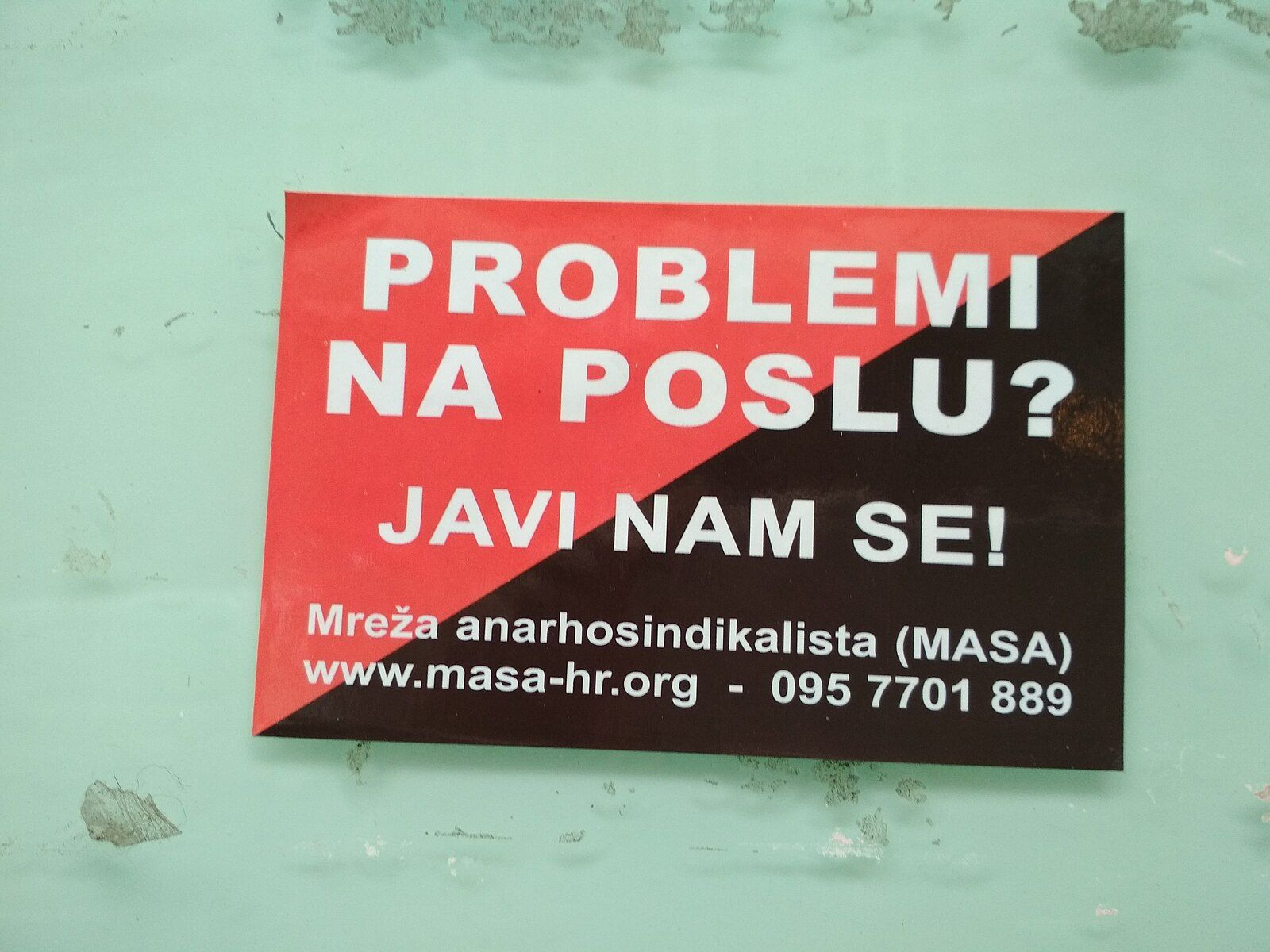

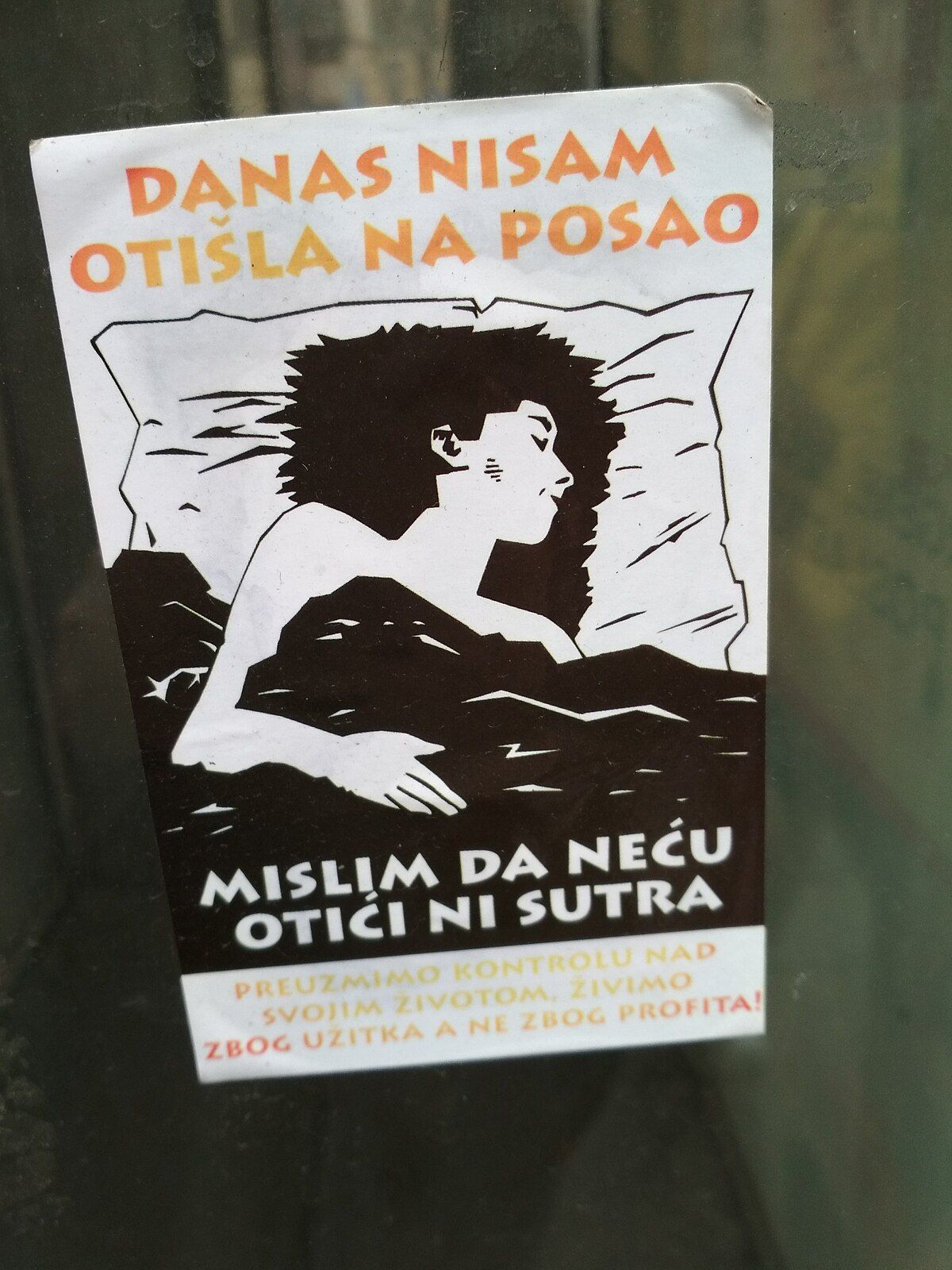

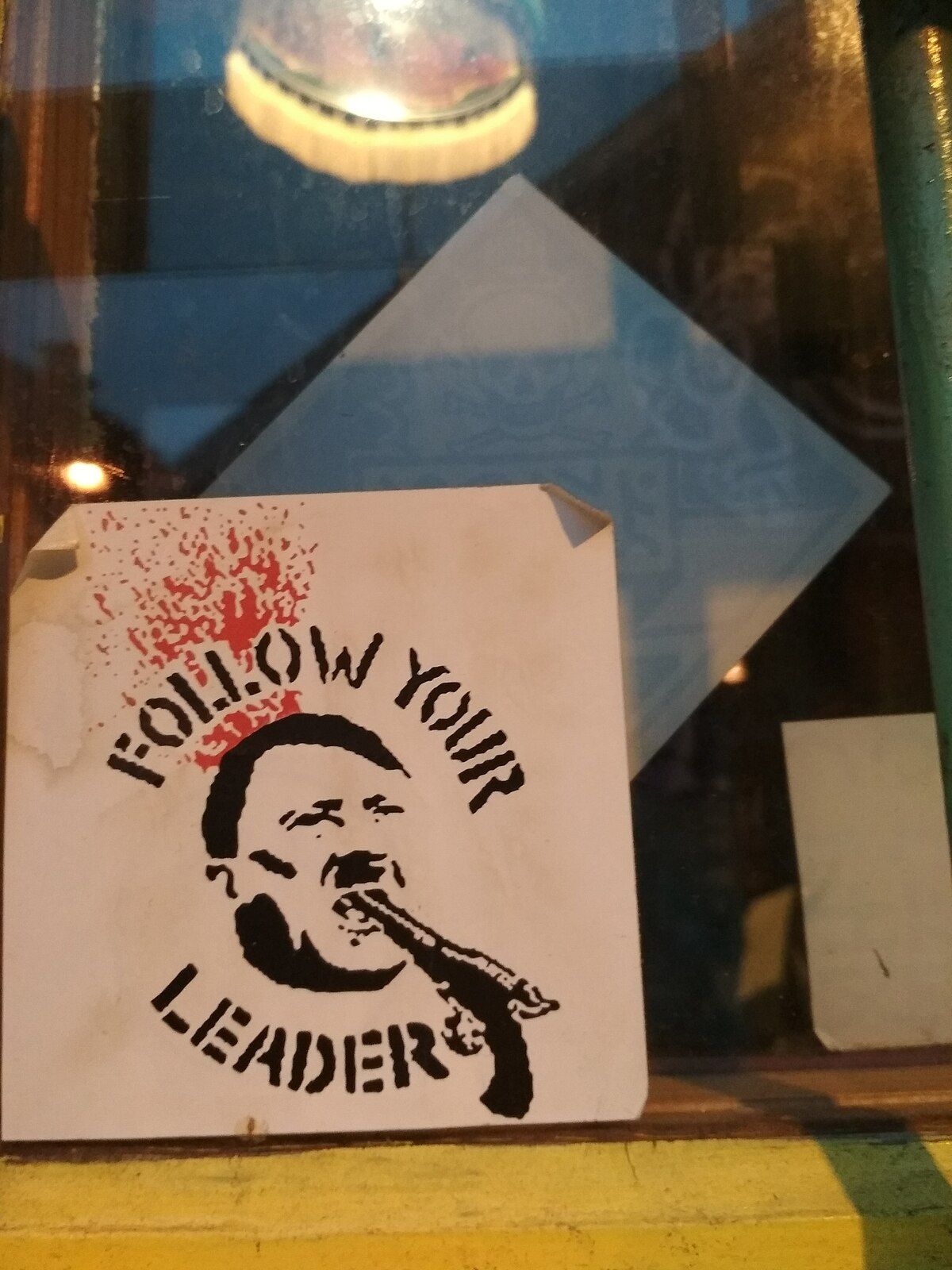

In both cities Antifa showed both humour and disdain for mainstream politics. One sticker, on the traditional anarchist black and red, mimics an ad from a bottom-feeding lawyer, reading ominously reading “Problems at work? Call us!” Another describes a woman who is skipping her work to stay in bed... and who'll do the same tomorrow.

The Ljubljana scene – bolstered by the antifascist strongholds of the Metelkova and Rog squats – is a hub for Antifa street art from throughout Europe. Using Google translate to decipher the various demands and witticisms was a real test of artificial intelligence: am I reading Croatian, Slovenian, Polish or something else? Some stickers, however, make their point clearly without English.

With Antifa sentiment so dominant in the city of Ljubljana, I imagine some of the resistance comes from places that are not the far right. In any situation that one ideology dominates, resistance may come any number of places.

Or maybe cops just get involved in the graffiti scene in Ljubljana too... I don’t know.

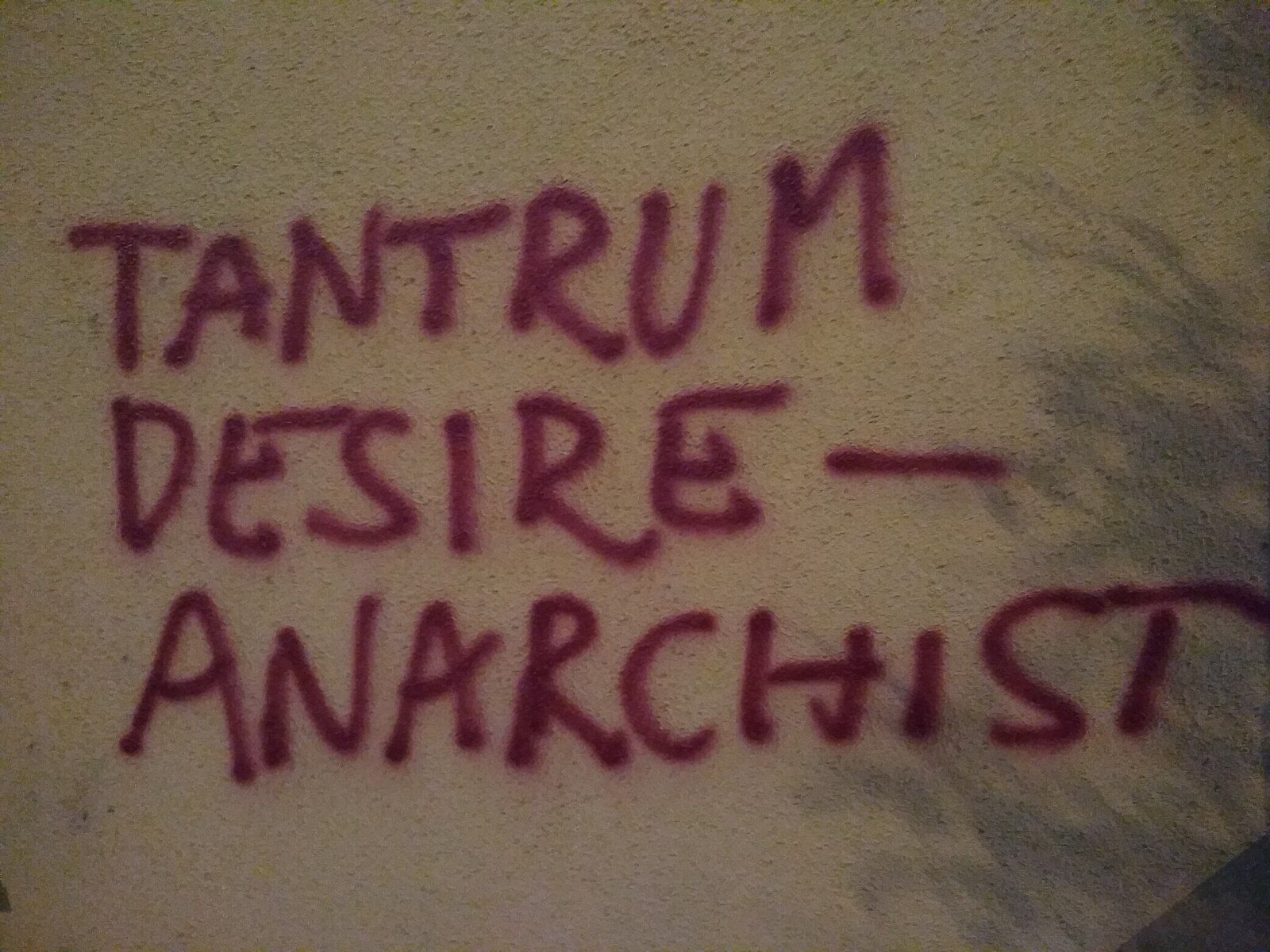

Ljubljana's most famous resident is Slavoj Zizek, and the place of the psychoanalytic school of the Ljubljana makes for an interesting juxtaposition with any binary reading of fascism and Antifa. Desire, resistance and impossibility all play a role in the struggle between the hegemony of Antifa in Ljubljana graffiti. I expect Zizek would be thrilled – enjoy your symptoms!

But most of those swastikas of Ljubljana were under erasure – undone, overwritten and obscured. Occasionally they felt less like an endorsement of Nazis and more like a clumsy attack on Antifa. As Greil Marcus describes in Please Kill Me the use of fluorescent swastikas by punks was meant as a rejection of the dominance of a postwar conformity. That those who used these symbols were shocked by the refusal of their viewers to see the postmodern bon mot shows both the enduring power of Nazi emblems and may explain the lack of use of these symbols by the far right in Hungary and Poland (as well, of course, as their association with German domination of both these countries during World War Two)

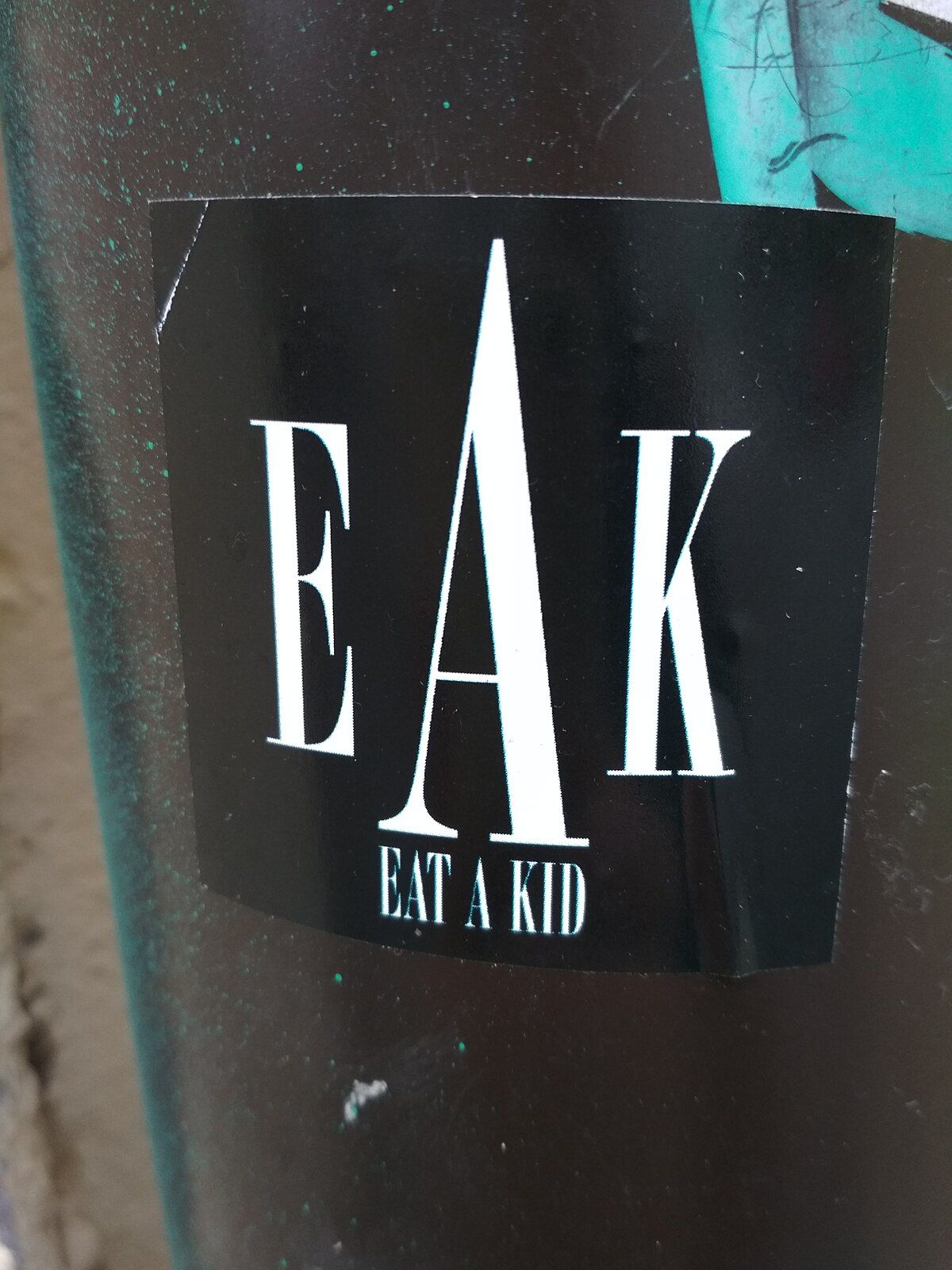

There are better ways to resist what feels like a domination of street art. First, we can resist the binary of fascism and anti-fascism by returning to Bataille's categorisation of excess and, specifically, the promise of art and invention, including inventive wordplay.

We might also take our categorisation to task through set theory by following the paradox that it is impossible to firmly establish the set of anything – fascists and antifascists; us and them – as those discrete borders rely on that which is excluded from them. For example, what have I missed by my framing of what counts as street art? Surely I have missed many small or obscure antagonisms.

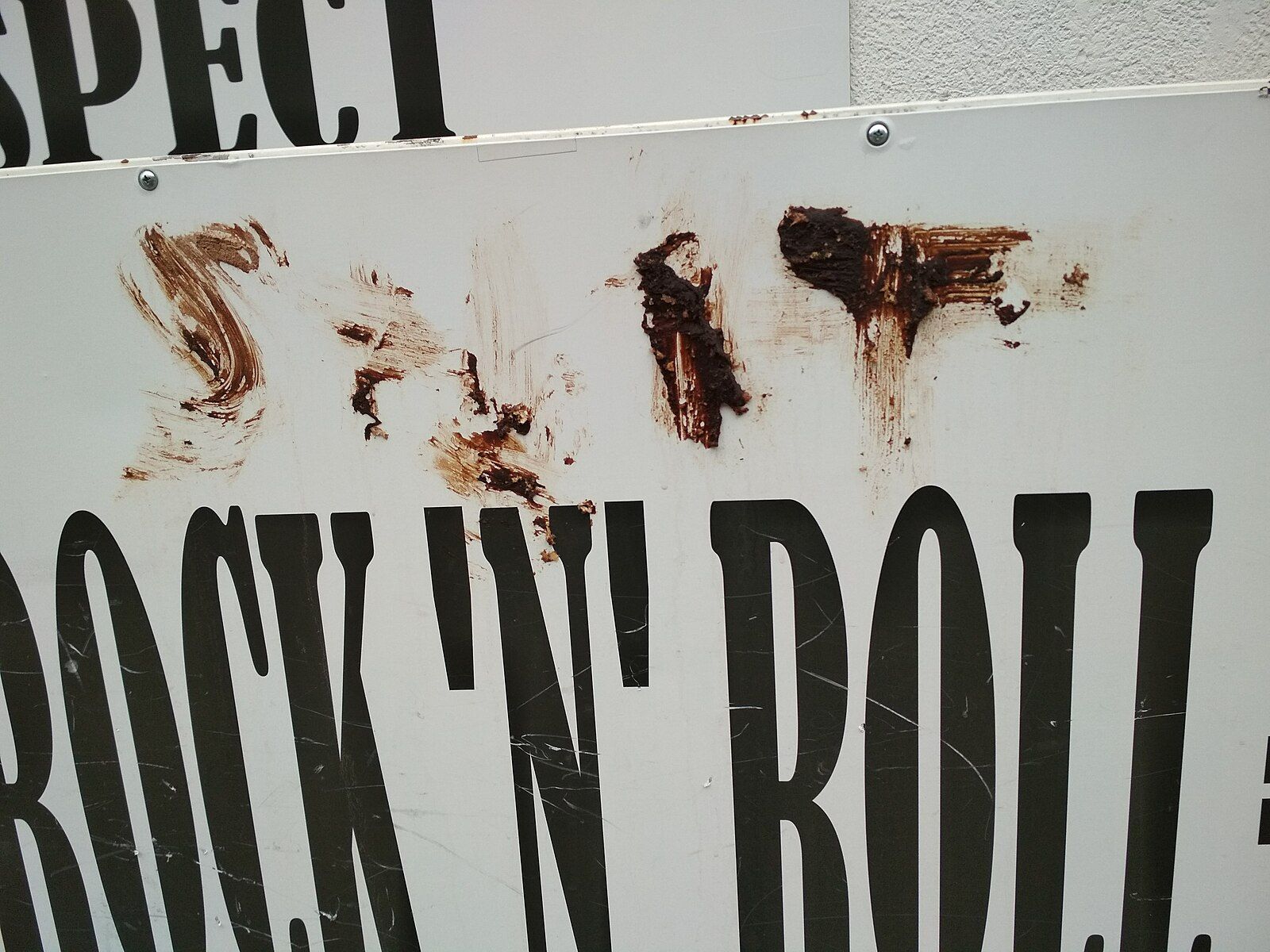

Nicholas Bourriard calls the attempt to find a form outside of that which is known or accepted 'the Exform' – neither formal, nor informal, but unworthy of being considered form. To him, this was the dominant direction of art in the previous century. Taboos like cannibalism and faeces are common refrains for this rejection of the status quo.

Nicholas Bourriard calls the attempt to find a form outside of that which is known or accepted 'the Exform' – neither formal, nor informal, but unworthy of being considered form.

The boundaries between exform and the formal/informal are difficult to interpret and, moreover, require interpretation as to what counts as art. There are two kinds of interpretations I will focus on, both of which rely on a disjunct between the artists and the observer.

First: for war, politics and sports the intention is for the audience to know fully well what the street art represents. But in art there is often a refusal to explain, and in that refusal an attempt to hold onto beauty. In this exform, the crusty diagonal cardboard of Budapest was certainly an intentional piece of art, but not exactly saying anything.

Second, there is the inverse of the above when there was never an intention to make art and yet a person walking on the street finds beauty. Note: the photo of what I call ‘picnic’ shouldn’t be seen as the art: that image was created after I saw the scene and recognised the sublime sculptural juxtaposition of Rákóczi street in Budapest.

Of course, these two views of where art is made but may not be recognised by a public, and where a public might recognise art which had no intentional maker does nothing to save those seeking to classify street art into sets. There remains the set of street art outside of both the perception of the creator and observer.

Additionally, as the world learnt with the first Nazis we also cannot privilege art, and the search for art’s limits, over war: sometimes war comes to us, and we must either die in a profound ethical act, or we fight back. Whereas the limits of art offer fascinating insights into the cultures we're a part of, war dumbly annihilates without insight. And so let's end with a classic series in black and red, leaving the absence of minor consonants and vowels as an open question.