The Eyes of the Atua

Literary Festival Programmer Claire Mabey on the transformation of children's book publishing in Aotearoa and, for Pākehā like her, its effect on the landscape of the mind.

When I was little, I never read or owned anything like the picture book The House that Jack Built by Gavin Bishop. It was published in 1999, when I was 11 and solely focused on my ambition to be a Spice Girl. The first time I read Bishop’s re-contextualising of the classic British rhyme was about a year ago as part of research for a project at work. I was astounded by it. Disturbed. With all of the precise elegance and cleverness of a children’s illustrator, Gavin reveals the colonial project. When Jack first lands in pre-colonial Aotearoa, the atua are everywhere, clear and strong. But by the time Jack has finished building his house (and introduced the rat that worried the cat…), the atua are barely there, a faded pair of eyes disappearing into a vast sky hovering over a landscape monumentally transformed by a brutal and blind invasion.

With all of the precise elegance and cleverness of a children’s illustrator, Gavin Bishop reveals the colonial project in The House that Jack Built

And in those faded eyes, I saw clearly, perhaps for the first time, that my own mind, my precious internal world, is a product of growing up in The House that Jack Built. Over my life, the atua have been almost entirely absent, and with them any knowledge of the character of the landscape that has held me and now holds my son.

*********

My son was born in 2018 and spent his first weeks as a premature baby in NICU. Incubators beeping and the smell of hospital hand-sanitiser were vivid features of his first home. It was a relief when we finally got to bring him to our little house among the trees, nicknamed The Treehouse. A few years earlier, when I first moved in, I was nervous to sleep and wake here. The house clings to a slice of hillside so steep that the foundations had to be anchored deep into the rock with long lengths of steel pipe. If you look out our lounge window, there’s nothing below but bush, and I wondered how it would go in an earthquake.

When the Kaikōura shudder hit in the middle of a Sunday night in November 2016, everything swayed and rippled, and I imagined extraordinary damage. But nothing shifted or cracked or tilted, and I learnt that the hundreds, thousands of trees doggedly planted all over our property hold everything together. Their roots have created a foundation of interconnected threads burrowing deep and wide to suck water from the scraggy coastal clay. Even if the topsoil slid down onto the road below, our house would still be standing, like a spider with its legs lodged into the cold rock and its knees cradled in a web of tree roots.

*

From this bird’s nest of a home our son has grown into a creature who makes friends with cicadas and tunnel-web spiders, and who collects kawakawa to make tea with and to keep under his pillow to ward off bad dreams. He knows the trees and their names – ngaio, horoeka, pōhutukawa, pāpāumu, kāraka, rangiora, puka – and it’s in their shadows that his imagination, the awesome dark and light of it, has flourished.

On weekends we hunt vampires. We put on gumboots and coats with pockets, and head over the road to Buckley Reserve, a dense swatch of regenerated bush running along and down into Houghton Valley. Once it was a tip site: a place where people stealthily tossed shopping trolleys and old bikes and fridges and other domestic detritus. Occasionally you will still come across a half-sunk frame of something long rusted and repossessed by a vine. For us, these ‘home wrecks’ are signs of trouble afoot: a vampire’s nest.

My son knows the trees and their names – ngaio, horoeka, pōhutukawa, pāpāumu, kāraka, rangiora, puka – and it’s in their shadows that his imagination has flourished

My son wears his red cape and carries a weapon of his own design: a whip of purple wool bound to a stick (really, a wand). It is very efficient at saving us from being bitten and our blood sucked. We are looking for Vernerkulus, Sheildah and Jandelah – three real bad vampires with gleamish eyes, long black coats with white buttons, and a nasty habit of lurking right around the corner. “Mum! Remember to check your neck for bloody holes!” When a stick cracks or a rock tumbles we crouch for cover in copsey nooks and try to stay silent. This is hard for my son, who chatters as fluidly as a pīwakawaka and with a range that astounds me.

*

These games ignite an old and familiar energy in me, and I am often transported back to my child mind. That feeling of creeping adventure unfolding from your own self and spreading out into the world around you. My games were somewhat different from my son’s: I used to force my brother and sister to play orphans with me. I relished a world without adults and made a ghastly orphanage in our lounge and fed us gruel (oats and cold water) and hid eggs under cushions so we could forage them back.

After a time in this terrible institution, we would discover that we each had frightening and marvellous powers. These would enable our breakout from The Orphanage and the start of a life as Nature Girl, Bush Boy and Jet (my little sister, a determined individual, could cease play at unpredictable times and exasperate the rest of us). Our game sprawled into territory way beyond our backyard and the Tauranga Boys’ College field on the other side of the fence. We were determined little colonisers taking our world out and onto the frontiers of the neighbourhood.

Our minds were populated, quite marvellously, by Roald Dahl, Judith Kerr, Shirley Hughes, Dick King-Smith, Margaret Mahy, Jill Murphy, Lucy Maud Montgomery and many others. But nothing of Aotearoa

Back then, the land and skies and the subterranean world underneath the dirt were unpeopled, blank. None of the books we read or that were read to us contained any information about where we lived. Our minds were populated, quite marvellously, by Roald Dahl, Judith Kerr, Shirley Hughes, Dick King-Smith, Margaret Mahy, Jill Murphy, Lucy Maud Montgomery and many others. But nothing of Aotearoa.1 The only memory I have of learning about a character from the ground I walked on was a children’s TV programme that re-enacted Tāne-mahuta pushing apart his mother and father with skinny little-boy’s legs. I can call it back easily, the earthy colouration of the film, and how sad it was that this young child’s mum and dad were now apart forever, but how happy I was that this little boy was so strong and could now run around with his brothers.

********

When we go vampire hunting, the northerly is often on our case.

“Tāwhirimatea! Stop blowing me!”

My son lifts his face to the skies.

“Tūmatauenga! Tāne-mahuta! You have to HELP US!”

He will call to the trees, to the shadows, urgent and pleading. And then he will mutter, as though wanting me to overhear his intimate relationship with his heroes, “Yeah, Tū will come and stop him.”

I’m a child of Jack, picking away at my own house to recycle, discard and clear away the junk so my son can see better

My son has whakapapa to Whakatōhea. We have shown him a picture of his ancestor, Ngāhiraka Wood: a black-and-white photo of a beautiful woman with moko kauae, eyes and nose in the shape of my partner’s, and an incredible high-collared fringed dress that I long to touch. I imagine that it’s silk, a rich red colour. But I try to keep my imagination away from her because she doesn’t belong to me. I want my son to know who she is and to have a connection with Ōpotiki and his marae. But at times, this is an awkward desire. I’m a child of Jack, picking away at my own house to recycle, discard and clear away the junk so my son can see better. But it’s my partner and son who are journeying towards Ngāhiraka, and everything that becomes visible to them on the way. I can only bring offerings on the road to aid their journey.

*

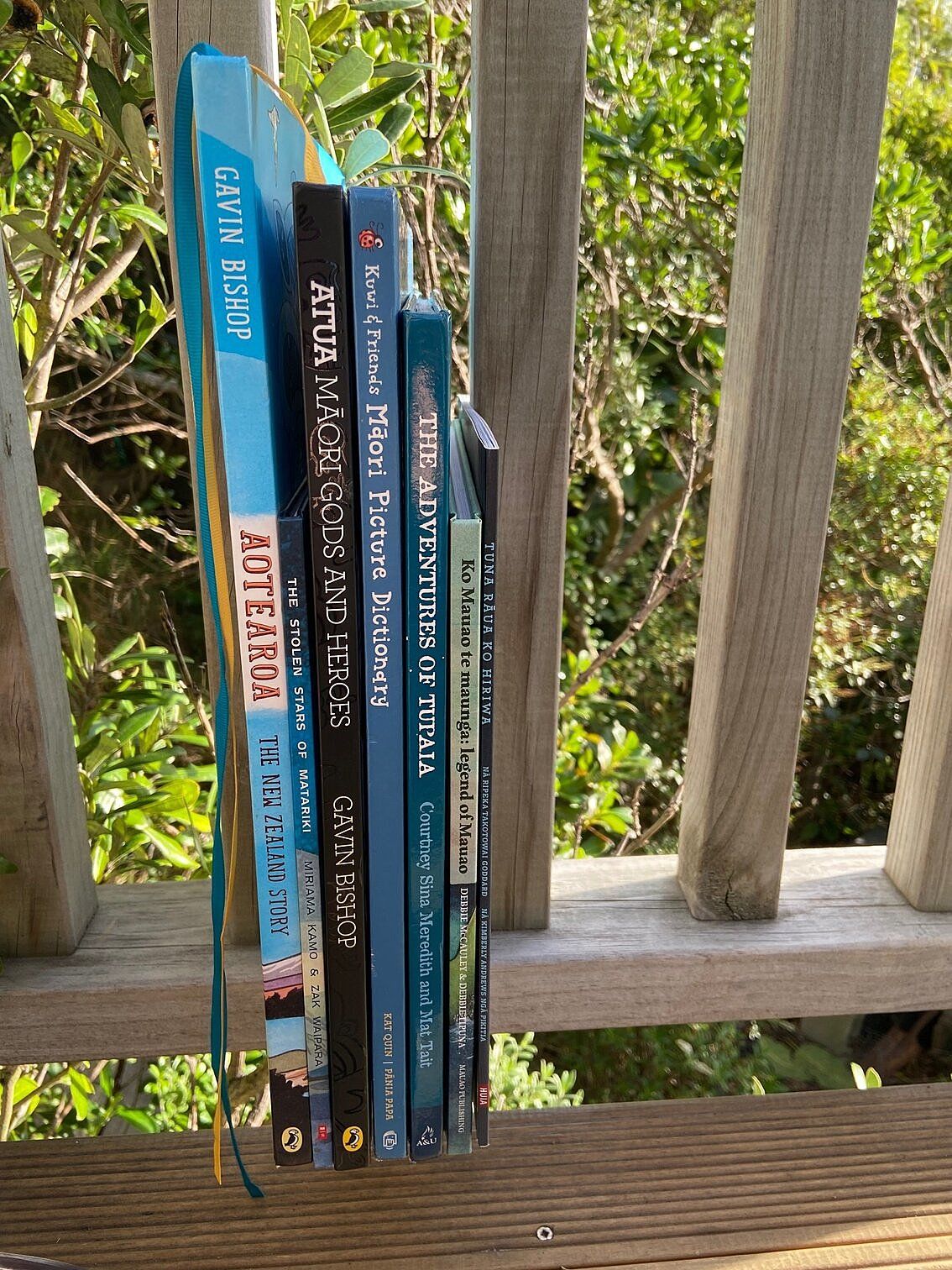

I do that in the best way I know how: with books. Gavin Bishop’s latest publications include Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes, and Aotearoa: The New Zealand Story. Together we read them over and over again. My son is enraptured from the vast black pages of Te Kore to the stirrings of Te Pō and the thrill of Te Ao. “That’s your favourite, eh Mum?” he points to Rongomātāne and becomes hushed when we reach Hine-nui-te-Pō. When he’s older, I will offer him Whiti Hereaka’s Kurangaituku. But for now, it’s Tūmatauenga who has captured his dreamland. Every night he begs me to tell him stories in which he and Tūmatauenga have an adventure, where Tangaroa steals him, and Tāne-mahuta and Tū go and fetch him back. They explode from the trees and skies, and have a secret trapdoor in our kitchen floor so they can drop in on us anytime. In Aotearoa: The Story of New Zealand,my son asks many questions about muskets and war: Gavin’s pages are infused with the reddish-brown figure of Tūmatauenga swirling through the land wars and later the World Wars. We go gently there because I can see my son’s lust for battle. I recognise it: how often had I constructed games where we fought our adult foe and won?

He begs me to tell him stories in which he and Tūmatauenga have an adventure, where Tangaroa steals him, and Tāne-mahuta and Tū fetch him back

There are many others besides Gavin Bishop: The Adventures of Tupaia by Matt Tait and Courtney Sina Meredith, My First Words in Māori by Stacey Morrison, Kuwi and Friends Māori Picture Dictionary by Kat Quin, How Māui Slowed the Sun by Peter Gossage. The view from the windows of our treehouse changes with every book we read. And book by book, we rebuild the house and shift the perspective.

As these stories furnish my son’s imagination, I can feel my own following behind him. When we walk in the ngahere, the atua are all around us, contributing to and flowing around our games. We are captivated by their moods, their push and pull, the dark, spirited world under our feet and the tiers of the cosmos above.

There are many others besides Gavin Bishop: The Adventures of Tupaia by Matt Tait and Courtney Sina Meredith, My First Words in Māori by Stacey Morrison, Kuwi and Friends Māori Picture Dictionary by Kat Quin, How Māui Slowed the Sun by Peter Gossage

On the wall above our piano is a painting by Sarah Laing. It’s part of a series of work that Sarah created during the 2020 lockdown, and in her astute and familiar way it captures our new world. A mother and daughter stand awkwardly to the side of a bush track while a father with a baby in a backpack passes below them saying “Thanks!”. A whole other dimension to our way through the woods: social distancing. We pass strangers with a fresh form of courtesy.

The landscape of publishing has transformed and, for Pākehā like me, so has the landscape of our minds

This behaviour is as natural to my son as having Tūmatauenga live in his imagination, Tāne-mahuta in the forest, Tangaroa in the sea, and Tāwhirimatea in the many winds. He is a child of the pandemic and of a new world of publishing. Without books, I would have struggled to have given him those stories and this knowledge. The landscape of publishing has transformed and, for Pākehā like me, so has the landscape of our minds.

What remains is a lot more story. New materials to build with. I can already see how different my son’s world will be with all the eyes of the atua on and around him.

1Until Mum gave me The Whale Rider by Witi Ihimaera, and that singular book impressed upon me a lifelong love of Witi’s work. I remember feeling something completely new. I loved Paikea, I think I wanted to be her. Free Willy was my favourite movie and I harboured a desire to replace that boy, Jesse, and be the one who rode the whale. But it was more than wish fulfilment – it was like a salt breeze through my mind. The thrill of recognition – something of the quality of the coastal world in which I lived in Tauranga was there on the page in a way that I couldn’t understand but that I could feel, and taste and smell. But this is a whole other essay.

Feature image: Anastasia Burn