Experiencing Art, Experiencing Others: On Community, Autonomy and Artist-run Initiatives

Hana Aoake considers ARIs past and present and imagines what 'community' could look like.

Hana Aoake considers ARIs past and present and imagines what 'community' could look like.

The love we make in community stays with us wherever we go.

bell hooks, “Community: Loving Communion”

The first time I went to a gallery I was nineteen years old. I had never really been interested in contemporary art before then, and hadn’t been exposed to much art at all beyond my Grandmother’s books on Monet, my parents’ tatty book filled with portraits Gottfried Lindauer had painted of some of my tūpuna, and another book on Salvador Dalí. My interest in contemporary art began when I started studying art history at university, initially attracted by a paper on art and fashion. My professionalisation followed not long after this, when I began volunteering and working at a number of galleries around Dunedin, and writing weekly exhibition reviews for a student newspaper. These experiences taught me first-hand how suffocating, intimidating and impregnable the art industry can seem when you aren’t upper middle class and you’re Māori. They made me wonder where art belongs, who it is for, and how we could make exhibitions where artists have autonomy.

In the art world, we use the word ‘community’ all the time, but what does it actually mean to us? How do communities function and why are they important? Can we imagine what a community should look like? How do we create communities we want to be a part of? Is it possible that exhibitions could help us form these communities, and if so, how?

We need to be asking: What do these projects operating outside of traditional institutional frameworks offer us?

I want to use this essay to consider these questions by looking at a selection of Aotearoa-based Artist-run Initiatives (ARIs) that I believe have placed an emphasis on centring the needs of artists in their projects, as well as building communities and facilitating ongoing conversations. Through looking at these spaces that operate to the side of formal institutions and commercial structures, I hope that we might better understand the nature and importance of community, and be better equipped to answer these questions imaginatively.

ARIs are often fraught spaces – theoretically based around the building and maintaining of meaningful relationships, often they just ruin friendships. ARIs are not sustainable – the maximum life expectancy for most is two to three years. They are frequently dysfunctional and unwelcoming, often just mimicking the institutional structures they claim to be in opposition to, and they tend to only serve a very specific community. There are numerous horror stories of ARIs that have crashed and burned, destroying relationships and ending in severe debt.

Many ARIs have been started following the typical model of a group of young artists, fresh out of art school, finding a site where they can have studios alongside a gallery space where they can show their work and that of their peers. Most of these initiatives are born from a desire to create alternative spaces for art that will serve a community of like-minded people. Often these spaces are small communities that are centred around people who care about the artists and the facilitators. Due to their short lifespans, ARIs tend to come and go in quick succession with very little criticality around how they functioned, what did and didn’t work, and how we can utilise their histories as models as we continue imagining what autonomy could look like. This isn’t to say they are not important, and that they do not facilitate a space for learning and the development of practices and relationships, rather that there is a need for greater reflection upon what these spaces have offered us. We need to be asking: What do these projects operating outside of traditional institutional frameworks offer us? One answer is that they offer us the potential to witness new modes of working with artists.

It is something that erodes agency and makes all galleries feel the same

Last year I began to research and reflect on these histories. I began to imagine how spaces for art could operate differently and offer artists more, because for me, most are still uncomfortable and function not that differently to a formal institution. This is partly due to the fact that many are answerable to the same funding bodies as larger galleries, such as local councils and Creative New Zealand, and that those which manage to stick around long enough eventually become professionalised, acquiring their own boards and structures of governance (Wellington’s Enjoy Gallery, Christchurch’s The Physics Room and Dunedin’s Blue Oyster Art Project Space all began as ARIs). Funding is great because you can pay your artists, but what is the point in paying an artist when you don’t care about their project? This isn’t to say that artists don’t deserve to be paid, but that there are other forms of generosity and compensation, and being beholden to these funding bodies determines the kind of work a space can show, and the audience they will have. For example, when ARIs aren’t answerable to a funding body, they don’t have to fulfil KPIs (Key Performance Indicators). These can essentially determine the structure of what an ARI can be by forcing them to have a specific programme showing certain kinds of artists. They also force a gallery to professionalise, with professionalisation often framed as being the goal, deemed as the only way of being ‘successful.’ For me, this is something that defeats the point of making a space for myself and my community. It is something that erodes agency and makes all galleries feel the same.

Their only curatorial concern was that the artists they invited experimented and made new work – perhaps wildly different to the work they were making at the time

The spaces that most interest me are always the ones that are bit loose. Spaces that perhaps aren’t interested in being professional – especially those that are run from people’s homes, or projects that aren’t tied to a physical site, or are polymorphic. For example, SHOW gallery ran in Te Whanganui-a-tara from 2004 to 2006, facilitated by Jenny Gillam and Eugene Hansen (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Mahuta) from a commercial warehouse building in which they also lived. The artists built the space in three parts: one part had studios and a laundry, the middle part was a gallery space and the final part was their central living area. Gillam and Hansen are partners, and work/worked full time as lecturers at Massey University while running SHOW, where they had a programme of exhibitions that each ran for three weeks at a time with a week in between for install and de-install. Their only curatorial concern was that the artists they invited experimented and made new work – perhaps wildly different to the work they were making at the time. The gallery functioned through volunteers who were either fine arts or art history students. Although SHOW looked and functioned much like many of our present artist-run spaces do now, it rejected a number of the conventions that remain integral to how most galleries function. Namely, no work was for sale, there were no wall texts or descriptions of the work or even artist statements. (There was, on occasion, a list of works and the name of the artist, but mostly SHOW would simply have an A4 piece of paper saying when they were open stuck on the wall and that was it.) Gillam and Hansen selected artists who were generally mid-career and who were, like themselves, relatively financially stable in comparison to younger emergent artists – which allowed for these artists to commit to their projects.

SHOW came out of Hansen and Gillam’s desire to have agency for themselves, and to support work and artists they had collaborative or ongoing relationships with by gifting them agency, too. The initiative was also a way of bringing together artists who they felt would work well together, often as a way of challenging artists to experiment without the more formal aspects inherent in most exhibition-making (like having a wall text). Hansen and Gillam continue to work together and tell me that they maintain their interest in how collaboration can build relationships – a response, perhaps, to the individualism rampant in contemporary art.

Most artist-run projects happen organically when the right circumstances arise. mother? is a space run by Leah Mulgrew and Selina Ershadi from the backyard of their flat in Freemans Bay, and is a perfect example of what happens when the right combination of people and place align. mother? was born when a friend suggested they turn their shed into a gallery and name it ‘mother.’ They liked the idea but were unsure about the name, so the project is known instead as mother?. mother? is a space invested in imagining autonomy through using the more sustainable – but still precarious – model of working out of your home. It is sustained through its reliance on a domestic tenancy agreement, the maintenance of relationships with flatmates and neighbours, and the temperamental nature of having a gallery in a suburban backyard where you have to contend with weather and mosquitos. Unburdened by the financial responsibilities of a more formal space and structure, mother? has the freedom to organise projects whenever and however they like. Accordingly, their exhibitions tend to occur on a small scale (usually only open for a few days over a weekend) and are often spontaneous. Recent exhibitions include Christina Pataialii’s Thoughts and Feelings, and Fool for a world that will end with Owen Connors and Daniel John Corbett Sanders (both 2018). Due to its small scale, and perhaps its domestic location, the audience of mother? tends to be made up mostly of people who come specifically to support the current exhibiting artist, alongside friends and supporters of the facilitators. Like most ARIs, mother? reflects a very specific community, but one which is grown through the generous hosting of artists and building of trust. However, this specificity raises further questions for me. Does an ARI need to be working towards creating a more expansive audience? Or can it just focus on serving a small community, and serving them well?

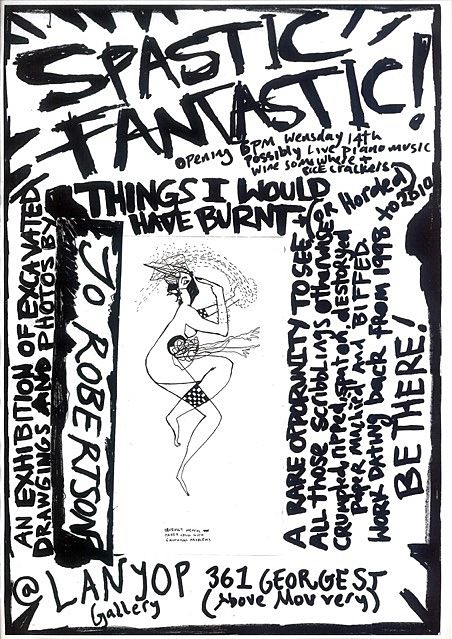

He would often serve rice crackers or biscuits and a tickle of wine

Another gallery borne out of living circumstances, generosity and creativity was {Lanyop} Lagniappe, a small space run by artist, designer, poet, curator, magician, teacher and musician, the late Larry Matthews. Larry ran {Lanyop} Lagniappe out of his home in Ōtepoti, which was located behind Mou Very, a bar on George Street. {Lanyop} Lagniappe took its name from a French-Cajun word meaning ‘a little something extra for nothing.’ It opened in 2010 and ran for one year, and was only open in the evening. The gallery came about after Larry failed to fill one of the rooms in his flat due to issues with the landlord, who ignored Matthews’ requests to fix leaks in the ceiling. Given the room was unliveable, Larry instead decided to turn the tiny room into a gallery. In the evenings, he would guide a small group of people – sometimes one by one – up a steep stairwell using candlelight, leading them into the gallery where he would play them piano while they examined work in the semi-dark, lit only by the candle. He would often serve rice crackers or biscuits and a tickle of wine.

Lanyop’s project was random. It was never a rolling stream of exhibitions organised every three weeks like most ARI projects. Instead, Larry showed his own work, which was often long-term projects, particularly photography, as well as inviting artists he knew – such as Jo Robertson, James Robinson and Motoko Kikkawa – to show in his home. He invited them to respond to the space, and to the conditions of the space, such as the fact it was only open at night, and that works were shown in near darkness.

Larry cared about building strong friendships and allowing artists the opportunity to show what they wanted. He opened his home to so many people outside of the immediate art community within Ōtepoti, due in part to the fact that it existed behind a bar. He cared deeply about how art and creativity could bring people together. Larry embodied the idea of manaakitanga, and without him the art community in Ōtepoti has never been the same.

In late 2010, after a number of run-ins with his landlord and subsequently the tenancy tribunal, Larry closed the gallery down. He posted the following statement on Facebook:

… I chose to change this grungy little room into a ‘gallery’ that symbolises life itself to me – through art and sharing and living with it. Art from myself. Art from others. Experiencing art. Experiencing others…

*

An ARI does not need to be confined to a physical location. This is evident in the creation of projects such as Hapori, founded in 2015 by artists Ayesha Green (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu) and Sorawit Songsataya in Tāmaki Makaurau. The word hapori is translated in the Māori Dictionary as a “section of a kinship group, family, society, community.” Hapori are deeply invested in discovering what this could look like by working with different strata of their art community based in Tāmaki Makaurau, and by actively seeking to work with people whose practices aren’t necessarily familiar to them.

It allows them to be malleable, and for unexpected projects to form in spaces not normally designated for art

Hapori is intended to be a “… project… untethered to any institution or artist-run space model. Hapori roams; is light-footed, peripatetic…” When I spoke to Green and Songsataya about why they chose not to have a permanent site, they described their desire to not be tied down to a building or a specific architectural space, which means that each group they work with can decide on their own context for the exhibition (which is refreshing when you consider that so many galleries, such as the Adam Art Gallery or the Govett-Brewster, are tied to difficult, often jarring, architectural spaces). It allows them to be malleable, and for unexpected projects to form in spaces not normally designated for art.

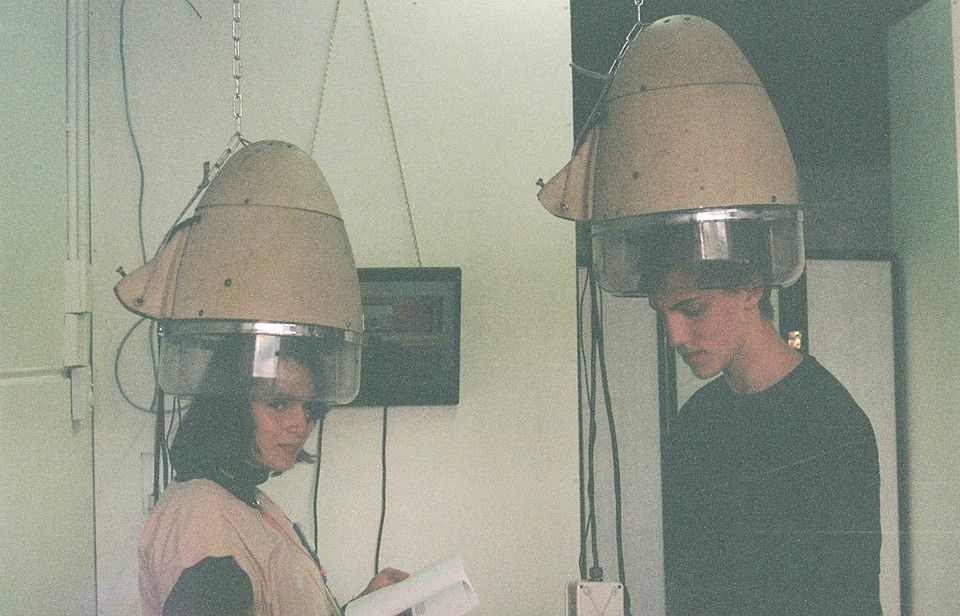

From 2015 until 2017, Hapori organised two shows and two publications each year (they are currently on hiatus). The exhibitions took place in various locations, such as Corban Estate Arts Centre, the Auckland Women’s Centre, Songsataya’s home and the site of the old Ferari ARI on Crummer Road in Grey Lynn. Each show lasted only a weekend. Green and Songsataya worked closely with either a group of artists or a single person, who might then choose to collaborate with others or organise contributions. For instance, Olivia Blyth’s project Communityity (2017) included an essay and two consecutive workshops conducted over a weekend, each designed around the premise of building a community more interconnected with the natural world. This exchange was imagined much like a wānanga, where participants were invited to contribute, eat and drink. In exchange, drawings they made during the workshop were collected and published within a Hapori publication.

Hapori work on each project for around six months, with Green and Songsataya helping to secure a site for the exhibition to take place. They do not see themselves as curators or directors, but merely as facilitators organising projects they feel will be beneficial to the artists they are working with, and to their broader community. Their strategy is to disrupt any kind of assumed hierarchy, and to focus on providing opportunities for different “… modes of exchange between ideas and art from learners, thinkers, artists, writers and audiences…” to take place.

*

I want to digress for a moment to consider a space that began as an ARI but has now been a fully funded institution with a physical site for many years. However, this year, having left the Tuam Street space they had occupied for 19 years (due in part to post-quake rent increases) and moved to their new site inside the Christchurch Art Gallery building, The Physics Room (TPR) has come to operate in a way that has more in common with ‘peripatetic’ projects like Hapori – for although their new site is more visible and accessible, it is not permanent. The money saved on rent has meant that TPR has more funding to devote to projects such as the (Un)conditional series. Being a smaller institution operating out of a much larger institution has meant that, as an organisation, TPR has had to assert their own identity and independence while also building relationships with other organisations. They have had to think more creatively about how and where they can enact projects, and this thinking has led them to re-examine their roots.

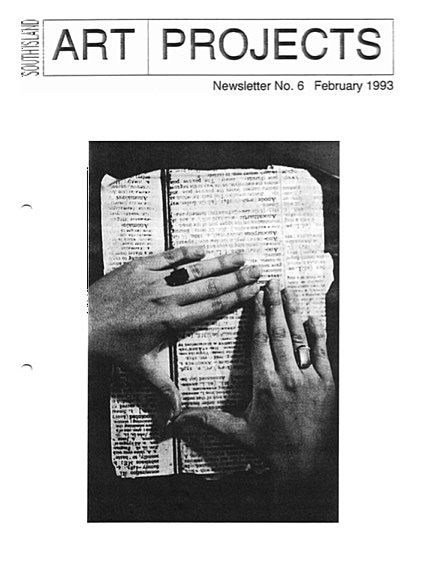

Like many other long-standing independent art spaces, TPR began initially as an artist-run organisation – the South Island Arts Projects (SIAP). From 1992 to 1996 (approximately), SIAP operated with an expansive view of how to organise projects. They produced a number of newsletters, seminars, talks and projects with larger institutional bodies, such as The Body of the Land/The Solutions Project (1992) for which SIAP partnered with Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Drawing inspiration from the SIAP, present-day TPR is seeking to follow a more polymorphic understanding of what exhibition making can look like. Accordingly, they have recently organised a number of workshops within Ōtautahi; have worked with other South Island galleries such as the Ashburton Art Gallery and The Suter to stage a number of shows in different contexts; have taken artists Ayesha Green and Cushla Donaldson to the Melbourne Art Fair; and have published two issues of their new journal, HAMSTER.

This kind of exhibition making is about reconsidering what collaboration can look like...

These recent projects have focused on the blending of the personal and professional, and on building relationships by bringing together disparate art communities from across Te Waipounamu – communities previously isolated from one another due to geographical restrictions. For example, for (Un)conditional I and V (2018), artists were invited to select an artwork from the collection of the Aigantighe Art Gallery in Timaru to show alongside new or existing works of their own. The specificity of this curatorial premise allowed the selected artists – Ana Iti, Clara Wells, Kerry Ann Lee, Miranda Parkes and Tim McLaughlin – to respond directly to the site and the history of Timaru by engaging with its collections.

From my position in Te Whanganui-a-tara, it is difficult to assess the success of any of these projects – to know whether they resulted in an expansion of TPR’s community, or more meaningful relationships between artists and curators. However, the fact that TPR are trying to do something of an experimental nature, and are responding to the urgent need for better relationships to exist between different institutions and communities, should be commended. This kind of exhibition making is about reconsidering what collaboration can look like, and is formulated around the idea of creating a broader context to support artists, both through the sharing of resources and through providing longer-term opportunities which allow them to build more meaningful relationships with curators, and with the galleries’ attendant communities. Of course, this experimental model is precarious and difficult, and hinges on the building and maintaining of relationships. As such, as a way to end the (Un)conditional series in November TPR will host a reflective hui where those who had been involved are invited to give feedback to evaluate those collaborations.

*

The experimentation underway at TPR seems to share many of the concerns held by now-defunct ARI Cuckoo. Cuckoo was a spaceless project based in Tāmaki Makaurau between 2000 and 2011, and was facilitated by a collective of artists – Judy Darragh, Daniel Malone and Ani O’Neill – and writers – Jon Bywater and Gwynneth Porter. Each person involved had prior experience working within a big institution or running self-initiated projects. Darragh and Malone had run the renowned Testrip gallery (1992-1998), which was started initially in Malone’s bedroom, while other members such as Bywater had been involved in initiatives like the High Street Project. Like Hapori, Cuckoo was a project that did not charge artists, but also did not pay artists or seek funding (I mention this idea of charging artists to show because it is common practice for ARIs in Australia). Again like Hapori, the decision not to seek funding was born from the desire to facilitate a project that was expansive, responsive and rejected the pressures of professionalisation, focusing instead on providing artists with opportunities to experiment. It was initiated to support artists and be of service to its own community, but it was also interested in how this community could become more connected. Indeed, in 2001 Porter stated that when building relationships between galleries and artists, Cuckoo was aware that “… the art world is a community, and if you don’t operate within your community, you’re alienated.” She spoke of the collective’s desire to “engineer social situations,” because “we don’t just put on openings, we consciously want them to be social situations, to get people meeting each other and talking.”[1]

This ‘gap-filling’ provided an innovative way to tap into the resources of established institutional and commercial spaces – such as their audiences and prime locations

Much like SHOW, Cuckoo organised a number of projects by working with artists they already had relationships with. And much like Hapori, they also organised events and made exhibitions in spaces where they might engage new communities. They often collaborated with public institutions such as the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the Govett-Brewster; with dealer galleries such as Anna Bibby Gallery and Sue Crockford Gallery; with local ARIs such as Rm401; and with international spaces such as First Draft in Sydney and Rooseum Centre for Contemporary Art in Malmö, Sweden. Their projects were often gap-fillers, utilising the empty time slots in between exhibitions, and ranged widely from screenings to readings, publications to exhibitions. This ‘gap-filling’ provided an innovative way to tap into the resources of established institutional and commercial spaces – such as their audiences and prime locations. It also disrupted the way many institutions typically have their programme planned out many months, even years, in advance: Cuckoo’s projects were fresh, could be responsive to the current moment and could lend their energy to fustier institutions.

The way they organised shows meant that they utilised their own personal networks, friendships that they had built over a long period of time.

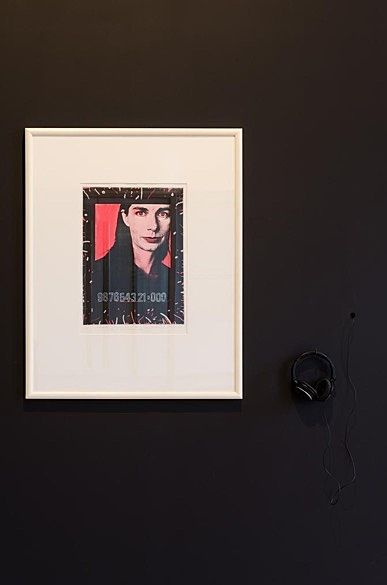

Cuckoo did not always curate their own projects. Rather, like Hapori, they often worked with external curators to facilitate an exhibition. For instance, No direct line from my brain to my heart (2003) was curated by artist Violet Faigan and took place at The Physics Room. The show featured drawings by Kirsty Cameron, Stella Corkery, Jad Fair, Alan Holt, Simon Cuming, Ann Shelton and Faigan herself. Cuckoo was reliant upon the building and maintaining of relationships, and was invested in generating conversation. The way they organised shows meant that they utilised their own personal networks, friendships that they had built over a long period of time. Through these relationships built between artists, curators and galleries, the collective were able to find locations to show works and to bring different kinds of artists together into these bigger institutional spaces.

*

In 2015, I started a physical ARI called Fresh and Fruity in Ōtepoti with Zach Williams (Ngāi Tahu). Much like Cuckoo, we wanted to create situations where artists could meet one another and where we could host them and their work. Hosting has always been important to us, and we like to do it in an almost over-the-top way – whether through serving desserts like panna cotta or pavlova at an opening, stealing enough flowers for a wedding to decorate the space, or hosting artists from out of town in our own homes for a number of days while we install and open their show. We created this space both out of urgency – other local ARIs like Glue gallery, Rice and Beans and A Gallery had recently shut down – and because we had the luxury of an affordable space being available to us (something which is easier to come by in Ōtepoti than in Tāmaki Makaurau or Te Whanganui-a-tara). As artists, we felt that many ARIs we had worked with took a slapdash approach to working with and hosting artists, so we made sure our mode of operating centred on the hosting and caring of artists and their ideas. We also made sure to never professionalise – because that would be boring, limiting and not something we are interested in.

We see ourselves as digital weavers, weaving fibre optic cables together in same way that Māori have utilised raranga for different purposes for hundreds, if not thousands, of years

After 18 months we left our physical premises and now run as a monster polymorphic project where we facilitate exhibitions, workshops, residencies and readings, as well as making our own work and engineering as many different kinds of opportunities for artists as we can. As a collective we have had many people come and go (members have included Zach Williams, Alannah Kwant, Kimmi Rindel and Severine Costa), but operate now with just two of us, Mya Morrison Middleton (Ngāi Tahu) and myself (Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Raukawa). Fresh and Fruity is polymorphic because we don’t ever want to be read as being a specific kind of ARI tied to a site or certain group of artists. We want the opportunity to always be growing. We see ourselves as digital weavers, weaving fibre optic cables together in same way that Māori have utilised raranga for different purposes for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. We are both an ARI and an art collective, producing writing, performances, merchandise and videos as well as organising events and exhibitions within bigger institutions, people’s homes, online and in other non-‘art’ spaces. Our investment in multiple modes of distribution, and in creating space and making work collectively, is a methodology I wish was more common within self-initiated artist projects. I struggle to understand why most ARIs strive to resemble formal institutions, rather than functioning as spaces for artists to experiment and have autonomy.

We work as a collective because, as Māori, that is the most natural way for us to work. We work as a collective because we are best friends, and the love and care we have for one another also means we are accountable to each other. The emphasis on individualism inherent in the art world and within colonial environments like Western universities not only wears us down, but it bores us. It’s uncomfortable for us to think about the process of demarcating whose idea is whose. We finish one another’s sentences. We illuminate different strengths in one another. We come together to reject the ideas of individualism ingrained within Western ideology, because we believe that our work is stronger together. As artists Quishile Charan and Salome Tanuvasa have asserted, the idea of demarcation has “… specific ties into ideas around possession and ownership, that are not only toxic, but inherently colonial…”[2] For us it’s important to disrupt the power of individualism, because we feel when we work together under the name Fresh and Fruity we are disrupting modes of colonialism

Our geographical isolation when we had a physical site in Ōtepoti meant that we began to seek opportunities to organise exhibitions in other cities, and to work with artists outside of our immediate communities via the internet. With the internet, it is increasingly easy to connect to a broader community, much like a wheke. When I think of the potentiality of expanding our communities, the internet seems like a logical place to begin – although it is also important to stress the significance of kanohi ki te kanohi. The first project we did offsite came about through our online network. It was a project called Showroom Apparel (2014), which was an exhibition we curated in a badly lit garage beside a design store in Sydenham, Ōtautahi. Showroom Apparel was part of a now-defunct seasonal street festival called First Thursdays, organised in Ōtautahi by Audrey Baldwin and Warren Feeney. We did this at a time when we still had a physical location; we had only had two shows, but we were always aware of the limitations of our HQ. We are currently working on our new website, which will (we hope) be able to create a more expansive and inclusive audience through alleviating geographical restrictions and reimagining how online galleries can host artists. The internet has enabled us to form and strengthen so many of our friendships, and has seen our community expand beyond Aotearoa.

*

What does community mean to us, and where can our communities exist? An art community can exist anywhere. It needn’t be tied to a specific kind of space or even to a physical space at all, but it should be centred around collaboration and meaningful relationships – this is what community means to me.

Young artists fresh out of art school who want to start their own ARI need to be reminded that they do not need to be reliant on paying rent they can’t afford for an architectural space painted perfectly white. You don’t need to have funding, a slick Mailchimp or even wall texts. You don’t need to professionalise. Hell, you don’t even need to start an ARI, maybe you could start a collective instead.

Each of the galleries, projects and collectives I have explored in this piece have had one thing in common – all have been focused on the creation of meaningful, long-term, reciprocal relationships out of a place of genuine love and care. Perhaps, if we each started to think about how atawhai could be embodied in each of our practices, then we might have a healthier and more meaningful art community.

In loving memory of Larry Matthews, who always had something to give and was one of the most generous people I have ever known. Many years later, I still think of him in every project I do.

Special thanks to the following people for allowing me to either interview them or message them annoying questions: Jenny Gillam, Eugene Hanson, Jamie Hanton, Ayesha Green, Sorawit Songsataya, Jon Bywater and Mya Morrison-Middleton.

[1] Gwynneth Porter is quoted here in a partial transcript of a presentation given by Cuckoo at the Waikato Polytechnic’s SPARC 2001. “Whakapapa,” in Cuckoo: January 2001–May 2003, ed. Warren Olds (Hamilton: Waikato Institute of Technology, 2003), 7.

[2] Quishile Charan and Salome Tanuvasa, “A Transcript,” in The sea brought you here, eds. Louise Rutledge and Sophie Davis (Wellington: Enjoy Public Art Gallery, 2017), 21.