Eschatology And The Perpetual Classical Music Apocalypse

No one has learnt to expect the death of classical music (and therefore, culture itself) like classical music purists. Celeste Oram takes a look why critics, musicians and composers are so preoccupied by The End, and dares to suggest what that End would look like.

I : PROPHECY

crisis

abandonment

extinction.

We are in grave danger of losing centuries of a wealth of wisdom and works.

There are hundreds of thousands of youngsters who now – through not learning or experiencing – have never even heard of Mozart or Beethoven. It is shocking and a disgrace that this has been allowed to happen.

One may ask, does it matter? Clearly it does, for the reason that the destruction of tradition—in all cultural fields—which went under the misleading heading of ‘progressiveness’ in the last century, represents a disaster. An immense treasure of wisdom, accumulated over the ages, is disposed of, as if it were a superfluous piece of ballast that would only hinder the flight of a glorious future. The assaults on tradition represent one front in a much larger war: a war over the tenor and shape of our culture, over our shared understanding of what the Greeks used to call "the good life for man". The attack upon the past is an attack upon civilization, and thus upon humanity: an alarming signal with implications for our entire civilization because it deletes an important learning trajectory about the human condition.

Classical music provides a most excellent way to go as deep as one can into our history and our understanding of humanity, of our expression and growth as people, and possibly, it gives us intimations of eternity. As an enlightened society, we are meant to aspire to more than mere entertainment. We are meant to allow great music in, to let it settle in our DNA, and to bask in the glimpse it offers us of a universe greater than we can otherwise imagine. This greatest of all art forms which transcends the material world – it’s the closest thing we have to God, goddammit.

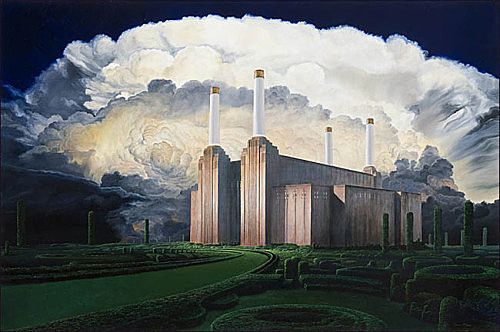

Every concert is a symbol of cosmic harmony. Every moment we deal with this great music, we are privileged to participate in cosmic harmony. It is this cosmic harmony which, in whatever form, must fill the world, and we, as musicians, must do our utmost to contribute towards this, through the music we know and love best. The passage of this realm out of our world would be tragic – even for the vast majority of people who have no interest in art that is made there.

For our consumer culture has achieved something more subtle and more penetrating than Lenin's Agitprop or Goebbel's Reichspropagandaministerium, or anything envisaged in a Huxleyan or Orwellian nightmare future. Each period of history, each phase of civilization has the art and music it deserves. If this is so, this music reflects something every bit as disturbing in our collective psyche as communism or fascism at their genocidal worst. Perhaps it will slowly become clear to us all in what this consists - and by then, it will be too late to make constructive change.

Gratefully quoted and synthesised from Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Nicola Benedetti, John Borstlap, Joshua Fineberg.

INTERMEZZO

Everyone loves a good apocalypse. Not just a trivial minority of eccentric religious fundamentalists awaits the rapture with rapturous anticipation; the secular human mind again and again proves itself gripped by eschatological preoccupation: a hang-up with the end times. Each age has their share of zealots convinced their generation must surely be the last, that the days they witness are the final ones.

No more succinctly is this eschatological anxiety expressed than in the two words "whatever next?!": the arch-battle-cry of the reactionary and the conservative. If language continues to be bastardized by digital communication, whatever next?! Human language will devolve into grunts and groans! If gay people are allowed to marry, whatever next?! People will soon demand the right to marry their dogs! The ultimate extrapolation of "whatever next?!" arrives at “what is the world coming to?!” or, "where will it end?" Obsessive disgust at the scatological triggers the eschatological imagination.

Yet doomsday anxiety is not a condition, but a symptom: a symptom of the telic hard-wiring of the Western mind. The Origin of the Species offered tidy scientific reinforcements for the train-track of progress and causality which history had long been organized into. The present seems far less illogical when framed as an inevitable destination. But the concept of evolution brought with it the threat of devolution, degeneration: that, having reached its apogee, the orbit of man could at any moment boomerang backwards – perhaps even into a darker shadow than the one it came from. And because the human imagination boasts incredible depth of vision looking backward, but much less focus looking forward, the present moment always has a strange aura of being the final destination. We are perpetually at the end.

Classical music has harboured anxieties about its own mortality for a very long time. As the late musicologist Charles Rosen famously quipped, “the death of classical music is perhaps its oldest continuing tradition”. No other art form has succeeded in making such a song and dance out of its death-rattle.

Although the classical music blogosphere insists on chasing its tail around the conversation, debating whether ‘classical music’[1] in fact is, or isn’t, dying is not actually very interesting (here’s the answer). What’s more interesting are the sources of classical music’s chronic hypochondria, causing it to perpetually obsess over its prognosis when really it is no more fit or frail than the average art form. Sure – not all classical music’s devotees are gripped by crippling pessimism; yet, even musicians with optimistic gumption captaining successful enterprises generally phrase their mission as ‘saving’ classical music. The words on everybody’s lips have long been, “whatever next?!”

It’s an anxiety hard-wired into classical music’s psyche by its two most pervasive obsessions: teleology and necrophilia. The necrophilia is abundantly evident in classical music’s veneration of dead people. (Granted, this is something it shares with Western culture at large.) Time is the only true litmus test for a work. By definition, New can never be Great, because it has not yet proven its sticking power or won enough knockout rounds. In fact, anything New that appears Great may well be Meretricious and should be treated with suspicion, for a work of True Greatness goes against the grain of its own time.

The teleology is what powers classical music’s artfully-constructed mythology. As noble as the attempt is to ‘just listen’ to a piece as ‘just music’, in practice, the entire tradition is symbiotically dependent on the giant game of dominoes in which its works have been laid out. The myth is a yellow-brick-road of progress: works get longer, tonality gets more complex, form gets more ambitious – until music is ultimately apotheosised by Beethoven. The saving grace of the murky, mystifying twentieth century is that little pathways can generally still be navigated between even the strangest of mutant offspring; it’s still a kind of progress. Critics scramble to herald precocious young composers as reincarnations of a forefather, in an attempt to prove the virility of the bloodline: Thomas Adès is the new Britten. Sometimes mixed marriages are okay, as they make for good PR—Nico Muhly is the lovechild of Phillip Glass and Björk—but great interpretive lengths are gone to in order to demonstrate pedigree in the paternal line.

Combine an exaltation of the old—at the expense of the new—and a chain-link view of music history, and you’re bound to succumb to a case of devolution anxiety. The music of the present day always seems so unstable because it is so nakedly un-canonized. For plenty of music-lovers, this is a freedom to bask in… while it lasts. But it’s hardly the bedrock that the classical tradition fancies itself founded upon. Classical music has spent most of its life on its deathbed because its insistence that its history is a train-track keeps ‘the end’ perpetually in its sights – especially when the music of the twentieth century has given so many occasions to ask, “whatever next?!”

“Whatever next?!” is really just one of two strains to classical music’s chronic anxiety. The other is that no-one cares about it. The two strains tend to follow one another like lines of counterpoint, each using the other as a scapegoat. No-one cares about classical music because it’s going off the rails. Classical music is going off the rails because it’s desperately trying to make everyone care about it. But the strains meet in unison when claiming what is at stake if classical music dies. This is the earth-quaking trump card.

Yet it gets played not so much in defence of present-day musical activity, but of dead-people music. Presumably this is because enthroning Beethoven as an international treasure is—comparatively speaking—not quite so touchily political a statement. Oh yes, he was German, but by now he is so dead that he’s everybody’s. A bit like that ‘scientific’ formula that calculates how many molecules of Shakespeare are in every living person. But claim that the music of George Crumb, or Peter Sculthorpe, or Jack Body, are vital to the trajectory of civilization – now you’re just being parochial. I mean, their music has importance on a national level, but humanity will probably still keep on trucking without it. Unlike Beethoven, which is of course the lynchpin of civilization. Remove it at your peril.

Go ahead and scoff – but there is touching pathos in the genuine humanist fear that classical music’s wavering health is an outward symptom of more insidious cultural decay.

What, exactly, do the prophets dread happening? Well, on a mercenary level, there’s the fear of unemployment . How vulgar to chart the decline of civilization in such mundane terms! But the ‘economic model’ of classical music is preposterous: an orchestra, or an opera, costs eye-watering amounts of money, many times more to upkeep than could ever be recouped in ticket sales. So classical music’s prestige is everything: if it suffers the slightest chink in its reputation as valuable and necessary cultural capital upon which civilization depends, it loses its privilege to demand vast sums of public, private and corporate money. Cultural saviour rhetoric is a sales pitch in disguise. Brilliant youth orchestras out of the slums of Caracas and Soweto are held up as shining beacons illuminating exactly how classical music is ‘for’ everyone: it’s ‘good for’ everyone. This young boy has been saved from poverty and destitution because he now can play a Mozart concerto breathtakingly well! [Sure, he still doesn’t have clean drinking water, but through our music he can transcend this hardship.]

It’s also worth noting that many of classical music’s most ardent lobbyists are composers. For them, even more is at stake: the anxiety of self-preservation extends beyond the grave. It would be disingenuous for a composer to claim that they don’t entertain even faintly glimmering aspirations of immortality; each work they write is a little graffiti carving on the rockface of art saying, “I was here”. So as long as Mozart and Beethoven occupy chapters and chapters in the history books, any composer whose work shares some DNA can hold out hope that they will feature in a footnote or addendum. Then their life’s toil will be validated; no-one wants to be remembered as the dinosaur of history .

Cynicism aside, the prophets do harbour a greater and more poignant fear. For cradle classical music lovers (of which I am one), the universe is contained within classical music. Its music and mythology are a rich library of tokens and totems for making sense of the human experience. So their fear is perhaps a more existential version of the very real threats facing the dwindling ethnic Samaritans, or the citizens of Tuvalu. If their artistic island is submerged, they will be cultural refugees, homeless aliens. The world will no longer recognize their cultural citizenship. On a personal level, this gives great cause for mourning.

But does it constitute an international state of emergency? What, really, is at stake if the entire classical music back catalogue—and the memory of it—fades into obscurity?

It’s a typical aesthete’s tendency to diagnose the health of a civilization by examining the state of its art. But classical music is gazing only as far as its own navel, and measuring only with its own yardstick. Usually ‘other music’ is held to trial as the enemy, the Trojan horse, or the imported species breeding classical music out of its rightful habitat in the hearts of the masses. Well-meaning but patronizing concerns are voiced that ‘popular music’ (always spouted as the antithesis of ‘classical’) can never truly fill the place of classical music; it lacks the refinement, the complexity, the depth of feeling. Classical music apparently has the hard-earned monopoly on transcendent truth and goodness, and without it, humanity risks forsaking its creative and intellectual potential.

If this is so, “why did the humanities not humanize?” indicts scholar Richard Taruskin, classical music’s best-paid iconoclast; “It is all too obvious by now that teaching people that their love of Schubert makes them better people teaches them nothing but vainglory and inspires attitudes that are the very opposite of humane. … To cast esthetic preferences as moral or ethical choices at the dawn of the twenty-first century is an obscenity.” An obituary for Ariel Sharon,the former Israeli Minister of Defense who shelled Beirut into ruins, reported that behind his desk Sharon kept a stereo, so that he could listen to violin sonatas; “he was a man of culture, who seldom missed a concert by the Israeli Philharmonic and was unfailingly courteous towards women.”

I feel a pang of sadness when I start to think of a world without Mozart and Beethoven. I find something special in classical music that I haven’t found anywhere else. I have had mega-transcendental experiences in the middle of Beethoven and Tchaikovsky symphonies. Teaching music for years has given me a body of empirical evidence from which to conclude that Ode to Joy and Twinkle Twinkle are the #1 smash hits among beginner piano students (in upper-middle-class Auckland suburbs). I love this music, and really do not want it to fade into obscurity. But can I defend its importance to anything beyond simply my own tastes?

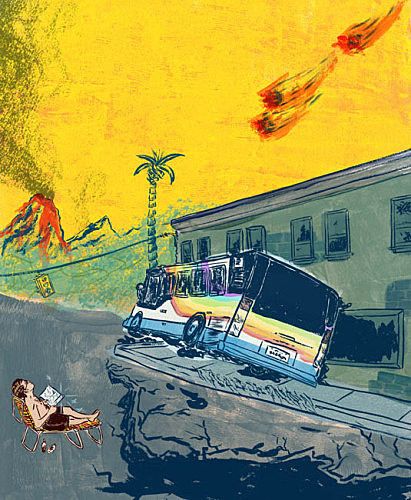

In an attempt to find out, let’s fast forward to the juicy bit. It has happened. The horsemen have charged, their dust has settled. And now, we tune into a report from the post-Beethovocalypse.

II : AFTER THE FALL

Somehow, through a sequence of events beyond the wildest dreams of the most fanciful eschatological imagination, we have lost centuries of a wealth of wisdom and works. Most people have never even heard of Mozart or Beethoven.

By a fate similar to that of the lost music of the Ancient Greeks, the scores and recordings of the entire classical tradition—and anything ever written about it—have all but vanished. What’s more, a collective amnesia has gripped all living humans, so acute that the vacuum goes entirely unnoticed. No-one remembers the music, or that it was ever there.

Once in a blue moon, a daughter or a son clearing out their late parents’ house will find a peculiar yellowing score or a cracked CD case. It’s a mystery as to what it is or where it came from; so it usually gets either biffed, or transplanted to another attic hermitage, resurrected only as a conversational curio at parties. Mention the name of a classical music mogul to even a well-heeled, well-educated sort, and it will sound to them either totally foreign or totally unremarkable.

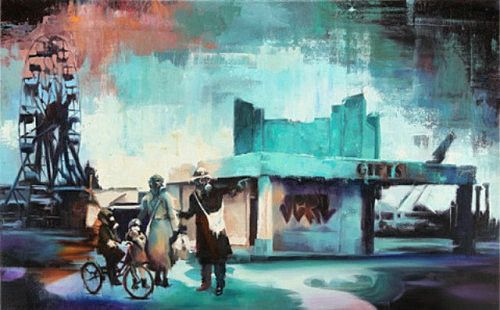

The post-Beethovocalyptic air is, of course, still throbbing with music. The art is surely robust enough to withstand the misplacing of a few leaves of parchment.But what kind of music survives?

All kinds you could possibly think of. The sheer scope and diversity of musical creativity is dazzling. There is music renowned for its extreme complexity and braininess; its elegance and perfection; its obscurity and strangeness; its banality and vacuity; its swagger and sexiness; its power, its grunt, its piety, its groove, its profundity, its escapist fancy. It’s music that dares to exude the hubris that artistic revelation is ongoing, not a limited resource. Sure, no-one says it quite like Beethoven; but then again, Beethoven failed to say it quite like today’s music does.

Playing and enjoying music together is a vital glue for communities, giving people of all ages pride and satisfaction. What they play is not really the point of the social enterprise; it’s the fact that they are enjoying music they love. Music’s power as a tool for self-identifying among individuals and communities is especially strong, because that process happens locally, and is constantly being re-negotiated. Not being able to trace music back to ‘where it came from’ doesn’t seem to stop people understanding what music means for them, now.

Because the past has been lost to amnesia, music is seldom condemned for being either ‘regressive’ or ‘innovationist’. Music isn’t thought of as moving forwards or backwards; simply the fact that it exists is evidence enough for its ‘relevance’. Not having to mud-wrestle over this title saves the post-Beethovocalyptic musician a lot of energy. Which is just as well, seeing as they actually have to work twice has hard as their pre-Beethovocalypse counterparts; they can no longer cruise through a career in hand-me-downs.

Ask a music-lover about the idea of ‘human universality’, and they will scoff as if you've put forward the idea of a flat earth. Without a soundtrack to demonstrate what is meant by an artistic minority when they describe their tradition as the most perfect articulation of the human condition, the myth struggles to hold up. As one New Yorker put it, we now see as ethnic what we formerly mistook for ethic.

Without an ‘ethic’ soundtrack, musical monoliths of noble human emotion like freedom, suffering, or transcendence are no longer available prêt-à-manger, ready to be reheated at short notice whenever occasion or catastrophe calls for it. Needless to say, this is an emotionally inefficient system. Whenever a wall comes down, people are required to think harder about exactly what their freedom feels and sounds like. When great masses die in violent and tragic circumstances, there is no longer a comfortingly familiar musical ointment that can be relied on to embalm the event as just another cinematic episode in the long march of human suffering. Instead of chasing ambulances, music confronts events and circumstances in their rawness and uniqueness.

One of the most severe conditions of the post-Beethovocalyptic world is that, without a canon serving as a safe contraceptive, music is proliferating at an alarming rate. It’s almost a pandemic. There is so much music in the world that trying to navigate a singular, definitive way through it all only leaves one mired in the glut, flailing helplessly. No matter how high an ivory tower you look out from, it is physically impossible to compile a singular, definitive map of the world’s music.

And so, people have given up. There is little attempt to crown a piece of music as ‘the greatest expression of x’, or revealing ‘the ultimate truth’. Music-lovers are resigned to the fact that it takes a whole tapestry of music to glimpse that, if such a thing exists.

But people tend to find in music what they’re looking for. Because, while no two pieces of music are quite alike, there’s a lot of music that points in a similar direction. It seems strange to talk of the particular notes of one single work as an algorithmic passcode unlocking hitherto unknown existential secrets. Was transcendence, or ecstatic truth, or fuck-yeah-ness—whatever you want to call it—ever really hard-wired into music? Or was it always there in the listener’s imagination, waiting to be conjured up no matter who was playing the tune?

Music is now the sonic expression of a continuous present tense. Which is really what music always has been: a temporal art that can only ever be experienced in the now: the present moment the only existing material thing; the memory of the past fast vanishing behind.

And so, there is no more eschatological hysteria. There is no more despair that our best work is behind us, that the torch is about to be dropped. There is still the latent anxiety that all art might be annihilated, that the entire sum of human creative thought and expression might one day go up in smoke. But whenever anxiety arises over one missing page of the book, or one faded corner of the canvas, the tendency is now to zoom out. To stand back. And see that the totality is still as brilliant as ever.

***

We shed as we pick up. Like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, what we let fall will be picked up by those behind. The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it. The missing plays of Sophocles will be written again in another language. Ancient cures for diseases will reveal themselves once more. Mathematical discoveries glimpsed and lost to view will have their time again. You do not suppose that if all of Archimedes had been hiding in the great library of Alexandria, we would be at a loss for a corkscrew?

[1] A footnote for pedants: I use the term ‘classical music’ metonymically for ‘the classical music tradition’ – i.e. not only the high art music written in Central Europe around the mid-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries (Mozart, Haydn, et al.) but the lineage of music written before and after it (up to this day), and the industry which has been, and is, its custodian. While the phrase is a misnomer, strangely, there isn’t a useful disambiguating alternative. Perhaps this is part of the problem.