A Colonising Moment: A Review of Lisa Reihana: Emissaries

Talei Si'ilata on Lisa Reihana's 'Emissaries' at the Venice Biennale, and making the European art world care about our postcolonial politics.

When Lisa Reihana was selected to represent New Zealand at the 57th La Biennale di Venezia with Emissaries, an exhibition that would primarily feature the panoramic blockbuster in Pursuit of Venice [infected], the choice was applauded by art lovers and critics alike, and rightfully so. The work is an ambitious undertaking, pioneering the latest digital animation technology to create a cinematic masterpiece, the first of its kind. The debut of in Pursuit of Venus [infected] or iPOVi at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in 2015 was one of their most successful solo exhibitions of a New Zealand artist, with over 40,000 visitors turning out to see it. As well as its mass-appeal, iPOVi also generated a critical response that sparked debate on representations of Pacific history and culture.

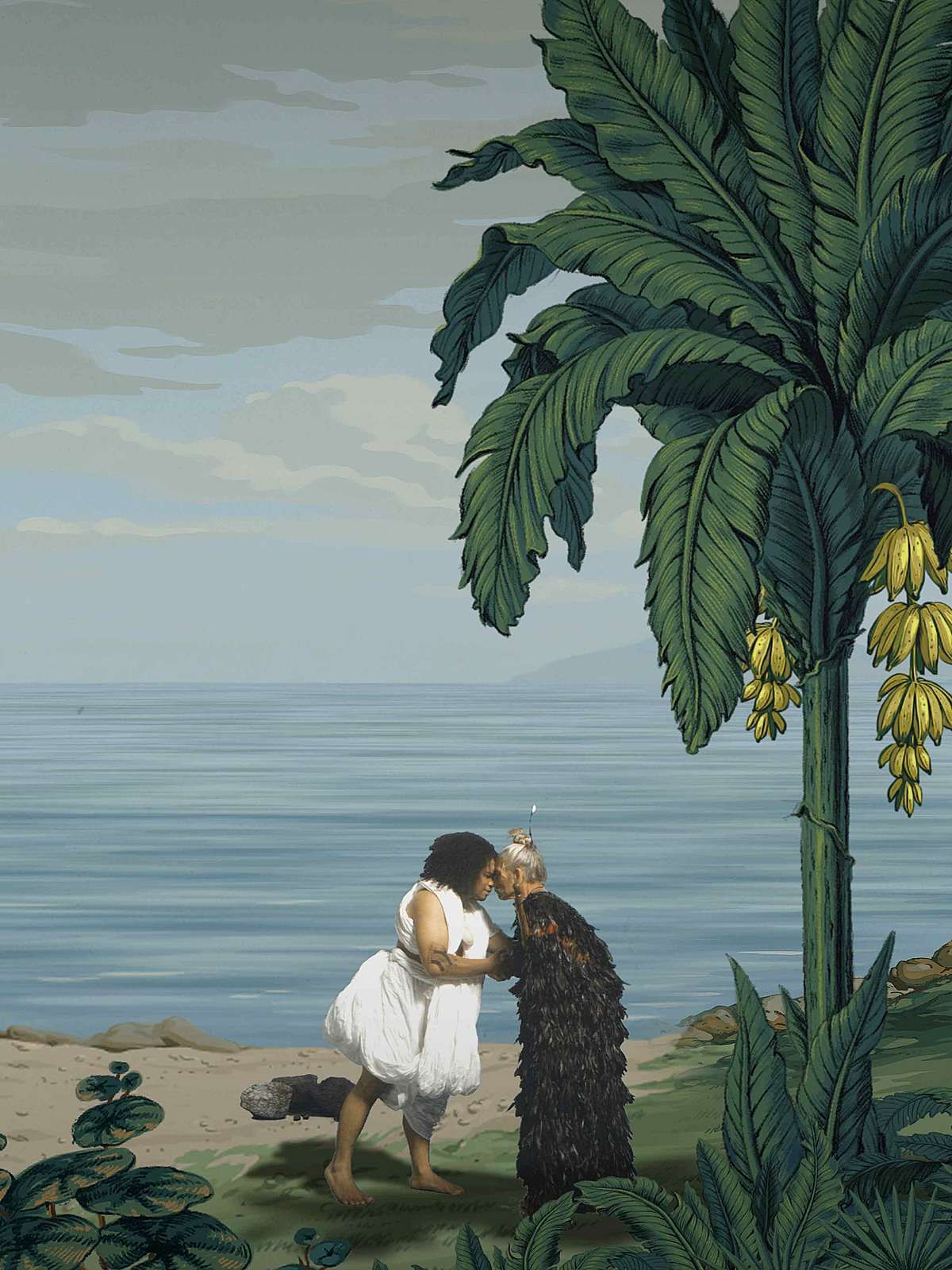

For iPOVi Reihana was influenced by a 19th century French wallpaper, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, which was originally illustrated by Jean Gabriel Charvet and published by Joseph Dufour in 1804-5. It is a product of the Enlightenment period and envisions a mythological Pacific paradise for European viewers. Supposedly drawing on the ‘discoveries’ of Captain Cook, de la Perouse and other explorers, the wallpaper falls drastically short of any accurate representation and instead depicts a neo-classical, quasi-fantasy view of the Pacific, with exotic figures that have more in common with Classical Greek or Roman sculpture than with brown bodies.

On the surface iPOVi seems to perpetuate a similar coloniser vs. colonised binary; a challenge that Reihana acknowledged as being part of reworking a 19th century wall-paper that epitomises ‘a colonising moment.’ However, in content and format iPOVi transforms this document, in a way that is both technically and conceptually innovative. In ‘re-animating’ Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique Reihana is not attempting to revive the romanticised vision that it presents. Rather, she is using it as a point of departure and a framework to work within, expertly disrupting the established power play embedded in it and returning the gaze, from viewed to viewer.

The Pacific people in iPOVi are also no longer passive, they gaze back at viewers and are active participants in a plethora of encounters that relate to a multiplicity of indigenous experiences within the colonial narrative; the good the bad and the ugly.

The original wallpaper was created for a European viewer and its multi-panelled panoramic format privileges the European viewer by arranging Pacific peoples along the periphery of the image. This metaphorically places Pacific peoples on the periphery of civilisation as well, reflecting the hierarchical system through which the Pacific was viewed by its colonisers. In iPOVi this hierarchy no longer exists as both Pacific and European people populate the digital-landscape. The Pacific people in iPOVi are also no longer passive, they gaze back at viewers and are active participants in a plethora of encounters that relate to a multiplicity of indigenous experiences within the colonial narrative; the good the bad and the ugly. This shift in perspective allows Reihana to activate lost moments of truth, while simultaneously appropriating and debunking a flawed, Euro-centric envisioning of the Pacific.

iPOVi buries the neo-classical stereotypes of Dufour’s wallpaper and instead imagines and recreates those initial encounters between Europeans and Pacific-Islanders that it ignored. The result is a stunning and immersive virtual world alive with scenes from all over the Pacific including Hawaiians, Samoans, Tahitians, Rarotongans, Māori, and even Aboriginal Australians, who are thrust into moments of contact and infection with European sailors, redcoats, the English Naturalist Joseph Banks, and even the explorer Captain Cook himself. Accompanying iPOVi in the Emissaries exhibition are two life-sized portraits; the first of Joseph Banks, and secondly the Chief Mourner, a ritual and spiritual figure in Tahitian society. Also included are a ‘constellation’ of repurposed telescopes that focus in on moments of colonial history and expansion.

As a young Māori and Pacific Island woman, the choice to have iPOVi shown at the world’s largest international art exhibition resonated with me on a personal level. I had studied Reihana’s work at University, written essays on iPOVi and its cultural politics but more than that, I identified with the desire to reclaim and retell Pacific histories in a way that championed contemporary conversations on indigeneity in Aotearoa. These conversations have moved away from confining indigenous peoples to a coloniser vs. colonised binary, and instead invert power structures to position indigenous people in a place of autonomy, and to encompass a wider variety of cultural narratives.

When Reihana was first selected for Venice there was criticism voiced by writer and critic Anthony Byrt, who remarked that iPOVi was in danger of fizzling out at the biennale because “it’s really hard to make the European art world care about our postcolonial politics.” Byrt made a valid point but his argument is not completely true. His mistake namely was assuming that postcolonial experiences are unique to us. iPOVi is undeniably and overtly about the Pacific, but this does not discount the work’s underlying and more nuanced dialogue on the universal human experience of colonisation.

His mistake namely was assuming that postcolonial experiences are unique to us.

I have no doubt that many of the viewers who walked into the old wooden building at the Tese dell’Isoloto in Arsenale, were drawn in by the works ‘exotic’ aspects. The distinctly foreign soundtrack featuring the chanting of Hawaiian mele, the somber Māori lament following Cook’s death as well as the visual feast of cultural costumes can easily be misconstrued to encourage an almost voyeuristic view of the Pacific. However, Reihana quickly does away with that notion by infecting the idyllic landscape with moments of rupture. The lasting impression viewers often leave with, which is the notion that these shared histories are much more complex than we realise, is very different to the initial assumption that iPOVi is merely a postcolonial tirade.

Working as the first exhibition attendant for the New Zealand Pavilion I found myself engaging in conversations with a young Mexican woman who likened English colonisers with the Spanish in South America, and with an Israeli man who admitted that seeing iPOVi made him reflect on the Jewish-Palestinian conflict and the notion of what land and homeland means to indigenous people. People who knew very little about Aotearoa or the Pacific found an affinity with the work, proving that while the European art world might not necessarily care about our specific postcolonial politics, they could definitely identify with colonisation as an experience which has been at play for centuries on every continent in the world affecting all parties involved, even the colonisers.

In our post-Brexit, post-Trump era the issues that iPOVi raises about cultural flux and upheaval, social injustice, national agendas and transnational relationships, and indigenous autonomy are all strikingly relevant to today’s social climate. And making those connections does not undermine the uniqueness of iPOVi as a Pacific work. We live in a time where ‘indigenous’ should no longer be synonymous with ‘marginalised.’ It is the specificity of our experiences; our unique histories and stories that should allow us to participate in, and not preclude us from global dialogues about global issues.

We live in a time where ‘indigenous’ should no longer be synonymous with ‘marginalised.‘

Tracey Moffatt certainly has no qualms about doing so. As the first-ever indigenous artist to solely represent Australia at the Venice Biennale, Moffat had a unique opportunity and made use of it. Her show My Horizon is comprised of two new photographic series; Body Remembers and Passage as well as two film works entitled Vigil and The White Ghosts Sailed In. Body Remembers features a maid (played by Moffatt) wearing a lace-trimmed black dress and apron as its sole protagonist. The series speaks to the history of domestic servitude forced upon Aboriginal woman and girls in Australia during the 20th century, many of whom were removed from their homes as children of the stolen generations.

Body Remembers is also a very personal reflection on these histories with Moffatt’s own mother and grandmother having worked as domestic slaves. Embodying this quintessential role, Moffatt positions herself in several scenes set within an abandoned country landscape featuring stone ruins and domestic interiors. The series poetically captures the protagonist’s deep sense of despair, isolation and mental confinement. However, there is also a sense of empowerment in Moffatt’s symbolic maid figure who dominates each photograph with a monumentality that is belied by her hidden face and turned back.

By choosing a protagonist that carries so much significance and weight with Aboriginal Australians and the history of holistic genocide they have been subjected to, Moffatt is making a statement about the importance of making indigenous experiences and histories not only visible but also valuable within Australia’s artistic vernacular. The White Ghosts Sailed In extends this idea, claiming to capture the exact moment of ‘invasion’ by Europeans into Australia and alluding specifically to the settlement in 1788. Another noteworthy feature of the show was the choice to include art that comments on the refugee crisis; a topic of heated debate within Australia. Vigil shows footage of “rickety boats overflowing with refugees adrift at sea spliced with white movie stars watching from windows.” The work is almost satirical, as it cuts between “desperate poor brown people in boats” and characters like Elizabeth Taylor who, with looks of fearful horror on their faces, watch their approach. Themes of surveillance, voyeurism and terror help Moffatt to explore the idea of privilege and refugee rights.

Similar sentiments are echoed in Tunisia’s offering The Absence of Paths, an exhibition that sees visitors participating in a performative form of individual protest, through the issuing of fake visas called “Freesas.” The Absence of Paths consists of three different kiosks positioned around Venice where visitors receive their “Freesas” and are required to stamp them with their thumbprint; an act the validates the fake travel documents and also symbolises their endorsement of “a philosophy of universal freedom of movement without the need for arbitrary state-based sanction.”

The Absence of Paths deals with the refugee crisis, and the consequent increase in the policing of borders. This stifling of human migration, which should be seen as a “symbol of our continued social evolution” is what the exhibition addresses primarily. Adding a further layer of meaning to the work is the presence of three young Tunisian men who man the kiosks and who have tried repeatedly to cross the Mediterranean in the past, and failed. These young men are living proof, not only of the restrictions put on many would-be migrants, but of the privileges offered to international art and cultural events such as the Venice Biennale, which under special circumstances granted the men one month tourist visas for their participation in the Tunisian Pavilion.

I saw these men almost every day for six weeks walking into the venue. As with any of the other attendants we would always exchange hellos and have the odd chat now or then. Their visa status or lack-thereof never occurred to me and I would never have assumed that I had been working alongside “refugees,” a term that later seemed inappropriate and dehumanizing, and which I was hesitant to use. The Absence of Paths provided a simple and but confronting look at the idea of a collective humanity and what that means in a world filled with contradictions and inequities.

Another related pavilion was Chile with Werken, an installation by another indigenous artist, Bernardo Oyarzún. Werken deals with the history of the repression of indigenous Mapuche people. Werken in the Mapuche dialect of Mapudungun means ‘messenger’ or ‘one who bears the word’. The installation itself features over 1500 masks made by artists of the Mapuche community, closely placed together on upright stands in the center of a room. Along the walls of the room runs an LED light banner, casting an eerie red glow on masks and also displaying 6906 Mapuche surnames which have survived “despite the historical state effort to erase their presence from the public sphere.”

According to Oyarzún the work focuses on a “territorial friction between the Mapuche people and the Chilean State.” The masks, called “kollong” are representations, and have a theatrical and ritual aspect which “disguises the Mapuche to exercise another function.” The 6906 names in a sense give life to the masks and activate a philosohpy of resistance and protest. Mapuche names, like their people, have been subjected to discrimination. In an interview Oyarzún explained how “there was a great loss of Mapuche surnames by order of the Chilean State—by decree—but also to escape marginality and racism.” Mispronunciation, misspelling and also mestizaje or “[race-mixing] that occurs between these surnames and others from outside” over time has also contributed to the erosion of Mapuche identity. However these names and the individuals and families they represent are a testament that the Mapuche remain a living nation. Werken therefore not only implies the transmitting of words through a messenger, but also the ability to poetically activate a space and to imbue it with memory, history and meaning. Oyarzún sees each name as a both Werken and Weichafe or a ‘warrior,’ referencing the fabled heroes and martyrs of Mapuche history but also referring to the ongoing conflict today between Mapuche peoples and the state. Werken is a thus a gesture of solidarity and continued defiance.

Our relationship to the international art world therefore constitutes a different set of ‘rules of engagement’ and in the case of the Venice Biennale, has provided a unique opportunity to speak within an indigenous rhetoric on histories and experiences that extend far beyond our borders.

What each of these exhibitions has in common is a deep understanding of the nuances between contemporary art, indigeneity and the state. For southern art centres such as Aotearoa, which have previously been on the periphery of the art world, our contemporaneity is being co-produced by a cultural climate that is constantly in flux, not only through the dynamics of our colonial past, but also in light of a culturally diverse population. Our relationship to the international art world therefore constitutes a different set of ‘rules of engagement’ and in the case of the Venice Biennale, has provided a unique opportunity to speak within an indigenous rhetoric on histories and experiences that extend far beyond our borders.

From a historical and migratory viewpoint, Aotearoa is one of the youngest nations in the world and we have only really just begun to partake in global dialogues offered through platforms such as the Venice Biennale. This makes Reihana’s work all the more significant and empowering as it brings to the fore important questions to do with multiculturalism and the trajectory of Pacific culture and identity in the 21st Century, while also reflecting on the fraught histories that have forged it.

iPOVi’s potency is fully realised in Venice; a site that speaks to the European age of empire and maritime exploration but which also activates and problematises the work within a universal dialogue on the progression of culture. It is both self-searching and externally cognisant of the wider world around us. in Pursuit of Venus [infected] revises our place and representation within colonial lore and simultaneously claims contemporary frontiers in media-based art forms as sites ripe for the political revaluation of such histories.

Lisa Reihana

Tese dell’Isoloto, Arsenale, La Biennale di Venezia

13 May 2017 – 26 November 2017

All images courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice.